| Builders

and Contractors

Although there are natural hazards in both developed

and developing nations, developing nations are often more damaged.

Even in the developing nations themselves, the most affected

segment of the population is the poorest one to the extent that

there’s a proposed mutual relation between natural disasters

and poverty (Freeman, 2000, Kreimer & Arnold, 2000). Several

hypotheses have been put forward to explain that trend: poor

people in general will have less of a choice when it comes to

where to live and how to build their houses. They spend more

time concentrating on other seemingly more urgent matters. (Kreimer

& Arnold, 2000) Nevertheless, the benefits of prevention

may be bigger than what many countries estimate (Parker, 2000).

One very important part of prevention is the introduction of

building codes and safer and more resistant building techniques.

In this way, builders and contractors can be targeted especially

to stop trends that exacerbate the risk of damage (Dilley, 2000)

The general populace is who ultimately will choose where to

build, how to build and with what to build their homes since

they are the ones who will be paying for it. Nevertheless; engineers,

builders and contractors do play a key role in making different

options available for the populace to make a better choice.

Our duty as an education group is to encourage the use of appropriate

technologies: i.e. those that are cost efficient. The decision

on which construction techniques are to be used is beyond this

group’s scope. I will firstly define the different sub-groups

that must be targeted and explain how can communication take

place. Different suggested options on how to not only communicate

but truly change the construction patterns in developing countries

will follow.

1.

Formal construction industry:

a.

Engineers: Although in developing countries engineers are not

heavily involved in many small scale housing construction projects

(Vermeiren, 2000) they should have the most expertise in building

techniques. If well prepared, Engineers could also play a role

in briefing government officials on the matter of tsunami safe

construction.

b. Real-Estate companies: these will create housing that will

then be sold to the general populace. A well informed real estated

company could increase the demand for tsunami safe houses.

The creation of technical manuals would be helpful (Vermeiren,

2000). I believe the quality of the engineers will be best improved

by including pertinent courses in local universities and higher

learning institutions. Also, the organization of technical seminars

and conferences would be recommended.

Enforcement

of the building codes is necessary. Moreover, the government

could issue a certification for ‘tsunami-safe’ housing

that will then imply taxing, insurance or loan incentives for

the buyers and sellers (Kunreuther, 2000) these will help people

differentiate between non-tsunami safe and tsunami-safe housing,

justifying slight but possible differences in price.

2.

The informal sector:

a. Masons: these are less technically instructed than engineers,

yet they comprise a bigger part of the construction industry.

b.

General public: in many cases the general populace is in charge

of constructing or partially constructing their homes (Vermeiren,

2000). In countries such as Peru, especially in rural areas,

many people build their houses themselves with the aid of their

families (United

Nations Centre for Human Settlements,

1989)

Much attention must be given to this informal sector, as it

is the main source of housing for the generality of the most

vulnerable population. Due to its lack of structure, this informal

sector will require different communication techniques than

those of the formal one. Parker (2000) indicates that communication

campaigns for builders and general public fail to be as effective

as they should be due to the size of the involved population,

the low ability to learn new techniques, the lack of time and

overly complex messages. Massive campaigns of communication

for tsunami awareness should include mention of better building

techniques. The messages should be coherent and succinct; Parker

suggests that ‘any presentation with more than three main

messages is ineffective’.

Community meetings directed to the groups in charge of construction

would be a way for not only transmitting information but gaining

feedback. In many cases international organizations (such as

the United

Nations Centre for Human Settlements)

have been involved in the training and technical support necessary

for builders to learn better building techniques. For instance,

in Peru, the

United Nations Centre for Human Settlements

helped establish training centers at building sites as well

as published construction manuals that explained the safer construction

methods (United

Nations Centre for Human Settlements,

1989). The government can also sponsor such programs or supply

them itself. Technical education is given by many governments

in developing countries and programs on tsunami safe construction

could be included, either as independent courses or a section

of a more general building course.

The attention issue is something we cannot overlook. Parker

indicates ‘the attention of the individual or potential

victim is a finite commodity that should not be misdirected’,

moreover, it seems that the time when people are the most susceptible

to listen is precisely after a disaster takes place: ‘reconstruction

projects promoting mitigations need to send the message during

the first months after disaster that safer housing is within

everyone’s reach. Once the idea is out, it can be reinforced

with classes, model buildings, and posters. But once the fear

engendered by the disaster event is gone, if people have not

heard that safer possibilities are available to them, the window

of educational opportunity has closed until the next disaster’.

Thus, after a tsunami has occurred and people are reconstructing

their homes is a very important time to create model houses

and demonstration projects which will have a strong impact.

Of course, the best would be changing habits before the tsunami

strikes, but in any case, the immediate period after a tsunami

presents a unique opportunity for education.

The publishing of national building codes by themselves that

aren't read by the population, or that cannot be afforded wouldn't

be enough. All the regulations, though necessary as they are,

cannot be imposed on people that cannot humanly follow them.

Kunreuther pinpoints reasons why there is not enough prevention

for natural disasters: underestimation of risk, costs, lack

of long term planning and expectation of assistance in the case

of a disaster. Thus if we are to change any bad habits there

are, we must tackle their causes. To avoid underestimation of

risks, mass communication campaigns could be effective. Safer

techniques could be made to look more cost effective to the

general public (Vermeiren, 2000). This can be done with the

facilitation of better loans and tax incentives for tsunami

safe properties, as well as long term low interest loans for

home improvement. (Kunreuther, 2000).

Although all the recommendations are based on general trends

researched in many different developing countries, we expect

them to be valid in Peru and the Federated States of Micronesia.

Field data should be used to verify whether these measures apply

to both countries.

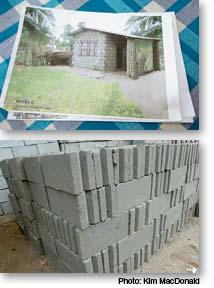

The

picture shows the kind of house that Habitat for Humanity is

building now in Sri Lanka. Habitat for Humanity is building

houses with better, cost-efficient techniques that will help

prevent the same amount of destruction that was seen in the

2004 Indian Ocean tsunami; this exemplifies how post-tsunami

education can have a stronger impact. Taken from: www.habitat.org/hw/2004tsunami/feature5.html

Sources:

-

Kreimer, A. & Arnold, M. (Eds.) (2000) managing disaster

risk in emerging economies. Washington D.C. World Bank. [includes

papers by Freeman, Kreimer & Arnold, Kunreuther, Vermeiren,

Parker, Dilley].

-

United Nations Centre for Human Settlements (Habitat) (1989)

Human settlements and natural disasters. Nairobi, United Nations

Centre for Human Settlements (Habitat).

|