Today, we talked about the relationship between BIBO stability and the

region of convergence. The neat result is that a system is BIBO

stable if and only if the region of convergence of the Laplace

transform of the impulse response contains the line

Re[s] = 0.

(17 cards)

-

What is the region of convergence? (1 student)

It's the set of all values of

s for which the Laplace

transform integral converges.

-

Why does it matter that the LT integral converges

absolutely as opposed to just converges? (1)

Even though the LT might converge (but not absolutely) at the

boundaries of the region of convergence, in the interior it will

generally converge absolutely, because the integrand will be

exponentially smaller (as

t goes to either

+

or

-

or

-  ) than at

the boundary of the r.o.c. That's good, because if the interior of the

r.o.c. includes

Re[s] = 0, then absolute convergence of the LT

is the same as convergence of

) than at

the boundary of the r.o.c. That's good, because if the interior of the

r.o.c. includes

Re[s] = 0, then absolute convergence of the LT

is the same as convergence of

| g(t)| dt | g(t)| dt |

|

-

Stop proving everything. We believe you. (1)

But you need to understand why these things works. It's not

satisfactory for me to just claim something is true -- you shouldn't

believe it unless I prove it.

-

So a system is stable if and only if the input and

output is BIBO. But you know input / output is BIBO if and only if

area of impulse response is finite, which means the region of

convergence of

G(s) includes

Re[s] = 0. Is this correct? (1)

Very close. A system is BIBO stable if and only if the area

of the absolute value of the impulse response of the impulse response,

which is true if and only if the region of convergence of

G(s) (the

LT of

g(t)) includes

Re[s] = 0.

-

Why do we define BIBO [stability] to be what it is? (1)

Two reasons: (1) The definition is reasonable, and (2) the

definition leads to a mathematically tractable result. Not every

reasonable definition is mathematically tractable!

-

So we can now determine if a system is stable. What is

the real world application? (1)

Every control system in the real world must be designed to

make the resulting closed-loop system stable.

-

If the impulse response must converge absolutely for

the system to be BIBO stable, are systems with impulse response that

are convergent (but not absolutely) conditionally stable, or

partially stable? What does it mean to be partially stable? (1)

First, I think you mean the integral of the impulse response

converges absolutely, not that the impulse response converges

absolutely. Second, there are definitions that lead to the idea of

neutral stability, which you called partial stability. Neutral

stability is a tricky idea, though. For example, a system with a

single pole at

s = 0 is neutrally stable, but one with two poles ate

s = 0 is not. It's easier to work with BIBO stability.

-

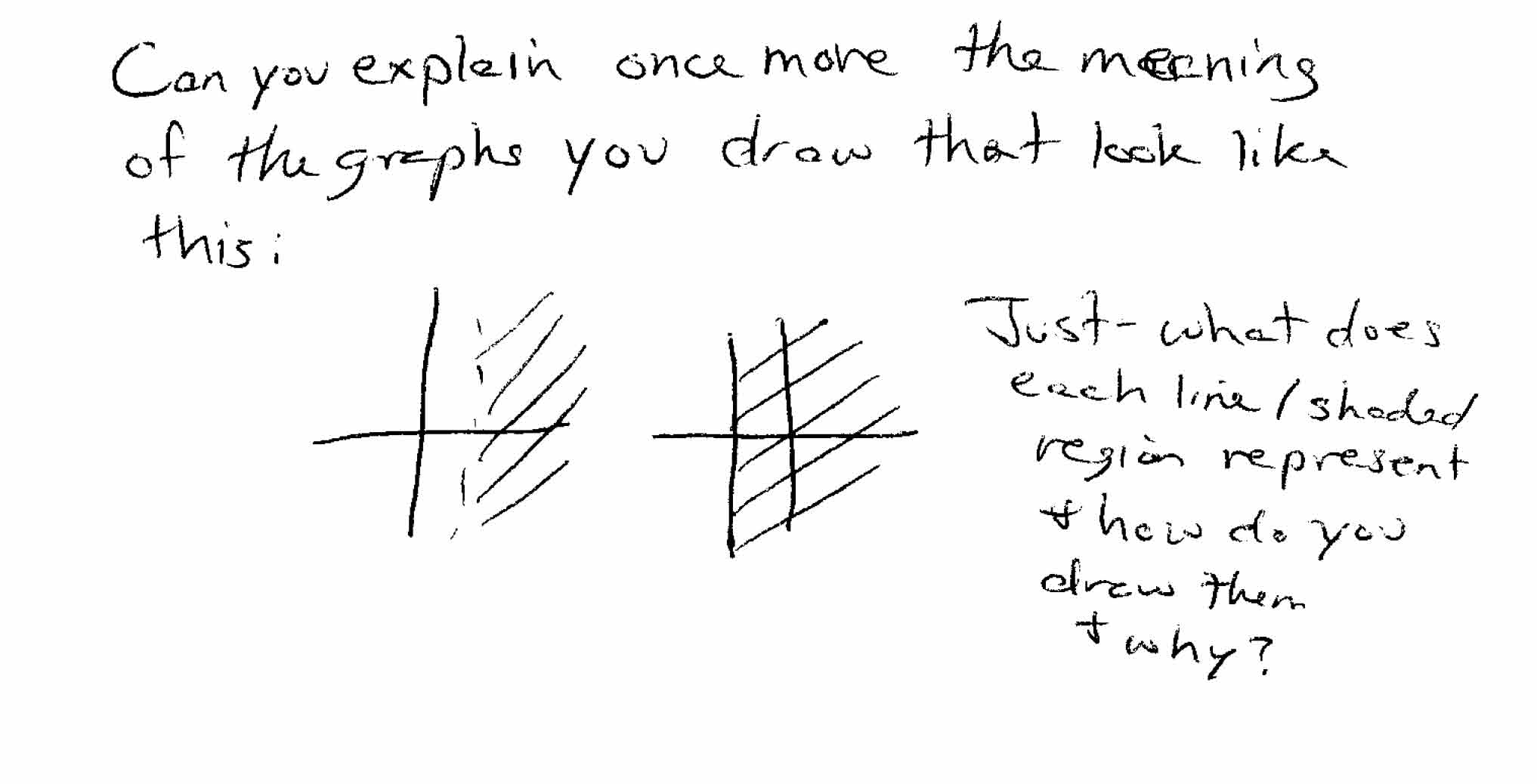

Can you explain once more the meaning of the graphs you

draw that look like this:

(1)

The axes represent the complex plane, of the variable

s.

The vertical axis represents

Re[s] = 0; the horizontal axis

represents

Im[s] = 0. The hashed region represents the region

of convergence (of the Laplace transform of some signal,

g(t)).

Since

G is stable if and only if the LT of

g(t) has r.o.c. that

includes

Re[s] = 0, the plot on the right indicates a stable

system.

-

What is a pole? What is the

j

axis? (1)

A pole is (roughly) where a function

G(s) is infinite. So

the function

1/s has a pole at

s = 0. As to the second question,

any complex number

s can be represented as

s =

axis? (1)

A pole is (roughly) where a function

G(s) is infinite. So

the function

1/s has a pole at

s = 0. As to the second question,

any complex number

s can be represented as

s =  + j

+ j ,

where

,

where

is the real part of

s, and

is the real part of

s, and

is the imaginary

part. The

j

is the imaginary

part. The

j axis is the axis where

axis is the axis where

= 0 -- it's the

vertical axis.

= 0 -- it's the

vertical axis.

-

Still confused about why the system is stable if its

region of convergence includes

Re[s] = 0. (1)

The answer is probably too long for a mud response. Briefly,

a system is BIBO stable if and only the integral

| g(t)| dt | g(t)| dt |

|

is finite. The integral is finite if and only if the integral

g(t)e-st dt g(t)e-st dt |

|

converges absolutely for

Re[s] = 0, since

| e-st| = 1 for

Re[s] = 0.

-

If

u(t) =  |

|

isn't

u(t) undefined for

g(- t) = 0? (1)

Yes. If I had been a little more careful, I would have

defined

u(t) = 0 for that case. The proof is still basically correct.

-

Why does

| g(t)e-j | g(t)e-j t| dt = t| dt =  | g(t)| dt | g(t)| dt |

|

(1)

Because

| e-j t| = 1.

t| = 1.

-

Why did you write the integrals today as

instead of

(1)

Because I was dealing with causal systems. It doesn't really

change anything.

-

No mud. (4)

A few comments:

Please don't lower your voice when

answering a question.

OK, will do.

I think board

work is good, but 1/2 the time should be used for Q & A.

I

can't promise it will be 50/50, but you make a good point, and we'll

do some of each.

When working at the board in recitation, I

would rather have a few minutes explanation (just of the setup) of the

problem to make sure that I understand what my group has done and that

it's correct.

We can try to do that, too.

Steven R. Hall

2004-05-16