Reading 7: Designing Specifications

TypeScript Tutor exercises

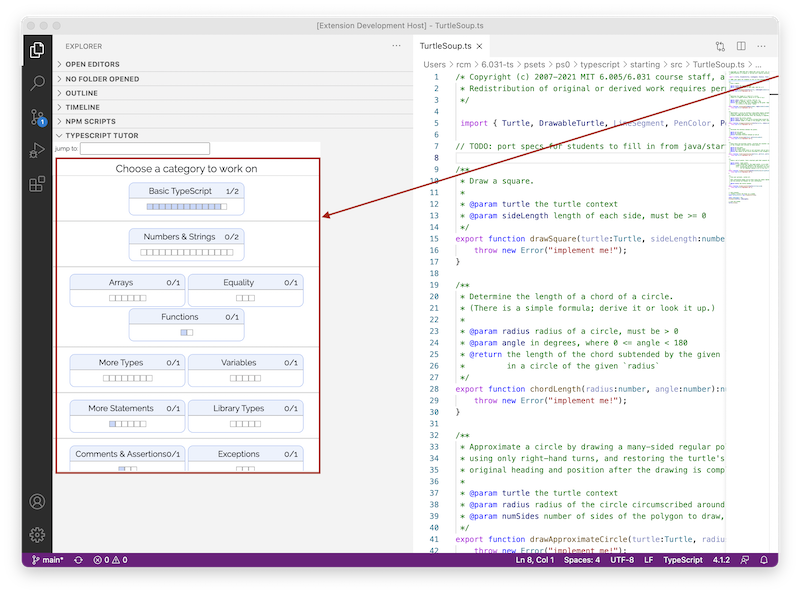

Keep making progress on TypeScript by completing this category in the TypeScript Tutor:

Software in 6.031

Objectives

- Understand underdetermined specs, and be able to identify and assess specs that are not deterministic

- Understand declarative vs. operational specs, and be able to write declarative specs

- Understand strength of preconditions, postconditions, and specs, and be able to compare spec strength

- Be able to write coherent, useful specifications of appropriate strength

Introduction

In this reading we’ll look at different specs for similar behaviors, and talk about the tradeoffs between them. We’ll look at three dimensions for comparing specs:

How deterministic it is. Does the spec define only a single possible output for a given input, or does it allow the implementor to choose from a set of legal outputs?

How declarative it is. Does the spec just characterize what the output should be, or does it explicitly say how to compute the output?

How strong it is. Does the spec have a small set of legal implementations, or a large set?

Not all specifications we might choose for a module are equally useful, and we’ll explore what makes some specifications better than others.

Deterministic vs. underdetermined specs

Consider these two implementations of find:

function findFirst(arr: Array<number>, val: number): number {

for (let i = 0; i < arr.length; i++) {

if (arr[i] === val) return i;

}

return arr.length;

}

function findLast(arr: Array<number>, val: number): number {

for (let i = arr.length - 1 ; i >= 0; i--) {

if (arr[i] === val) return i;

}

return -1;

}

The subscripts First and Last are not actual TypeScript syntax.

We’re using them here to distinguish the two implementations for the sake of discussion.

In the actual code, both implementations should be TypeScript methods called find.

Since we’ll be talking about multiple specifications of find too, we’ll identify each specification with a superscript, like ExactlyOne:

function findExactlyOne(arr: Array<number>, val: number): number- requires:

valoccurs exactly once inarr- effects:

- returns index

isuch thatarr[i]=val

The findExactlyOne specification is deterministic: when presented with a state satisfying the precondition, the outcome is completely determined.

Only one return value and one final state is possible.

There are no valid inputs for which there is more than one valid output.

Both the findFirst and findLast implementations satisfy the specification, so if this is the specification on which the clients relied, the two implementations are substitutable for one another.

Here is a slightly different specification:

This specification is not deterministic.

It doesn’t say which index is returned if val occurs more than once.

It simply says that if you look up the entry at the index given by the returned value, you’ll find val.

This specification allows multiple valid outputs for the same input.

Note that this is different from nondeterministic in the usual sense of that word. Nondeterministic code sometimes behaves one way and sometimes another, even if called in the same program with the same inputs. This can happen, for example, when the code’s behavior depends on a random number, or when it depends on the timing of concurrent processes. But a specification which is not deterministic doesn’t have to have a nondeterministic implementation. It can be satisfied by a fully deterministic implementation.

To avoid the confusion, we’ll refer to specifications that are not deterministic as underdetermined.

This underdetermined findOneOrMore,AnyIndex spec is again satisfied by both findFirst and findLast, each resolving the underdeterminedness in its own (fully deterministic) way.

A client of this spec can’t rely on which index will be returned if val appears more than once.

The spec would be satisfied by a nondeterministic implementation, too — for example, one that tosses a coin to decide whether to start searching from the beginning or the end of the array.

But in almost all cases we’ll encounter, underdeterminism in specifications offers a choice that is made by the implementor at implementation time.

An underdetermined spec is typically implemented by a fully-deterministic implementation.

reading exercises

With the same two implementations from above:

function findFirst(arr: Array<number>, val: number): number {

for (let i = 0; i < arr.length; i++) {

if (arr[i] === val) return i;

}

return arr.length;

}

function findLast(arr: Array<number>, val: number): number {

for (let i = arr.length - 1 ; i >= 0; i--) {

if (arr[i] === val) return i;

}

return -1;

}

function find(arr: Array<number>, val: number): number- requires:

- nothing

- effects:

- returns largest index

isuch thatarr[i]=val, or -1 if no suchi

(missing explanation)

For each spec below, say whether it is deterministic or underdetermined.

function find(arr: Array<number>, val: number): number- requires:

valoccurs exactly once inarr- effects:

- returns index

isuch thatarr[i]=val

(missing explanation)

function find(arr: Array<number>, val: number): number- requires:

- nothing

- effects:

- returns largest index

isuch thatarr[i]=val, or -1 if no suchi

(missing explanation)

function find(arr: Array<number>, val: number): number(missing explanation)

Declarative vs. operational specs

For this dimension of comparison, there are two kinds of specifications. Operational specifications give a series of steps that the method performs; pseudocode descriptions are operational. Declarative specifications don’t give details of intermediate steps. Instead, they just give properties of the final outcome, and how it’s related to the initial state.

Almost always, declarative specifications are preferable.

They’re usually shorter, easier to understand, and most importantly, they don’t inadvertently expose implementation details that a client may rely on (and then find no longer hold when the implementation is changed).

For example, if we want to allow either implementation of find, we would not want to say in the spec that the method “goes down the array until it finds val,” since aside from being rather vague, this spec suggests that the search proceeds from lower to higher indices and that the lowest will be returned, which perhaps the specifier did not intend.

One reason programmers sometimes lapse into operational specifications is because they’re using the spec comment to explain the implementation for a maintainer. Don’t do that. When it’s necessary, use comments within the body of the method, not in the spec comment.

For a given specification, there may be many ways to express it declaratively:

function startsWith(str: string, prefix: string): booleanfunction startsWith(str: string, prefix: string): booleanfunction startsWith(str: string, prefix: string): booleanIt’s up to us to choose the clearest specification for clients and maintainers of the code.

Note that these startsWith specs have no preconditions, so we can omit requires: nothing for the sake of brevity.

reading exercises

Stronger vs. weaker specs

We discussed in the last reading (Specifications) how the presence of a spec allows you to replace one implementation with another safely, as long as both implementations satisfy the spec. But suppose you need to change not only the implementation but also the specification itself? Assume there are already clients that depend on the method’s current specification. How do you compare the behaviors of two specifications to decide whether it’s safe to replace the old spec with the new spec?

To answer that question, we compare the strength of the two specs. A specification S2 is stronger than a specification S1 if the set of implementations that satisfy S2 is a strict subset of those that satisfy S1.

A predicate maps its inputs to true or false.

We often implement predicates in code as boolean functions, e.g. isEven(n) returns n % 2 === 0.

In specifications, the precondition is a predicate on the inputs, and the postcondition is a predicate on the outputs.

And a specification as a whole is a predicate on implementations: either an implementation satisfies the spec or it does not.

This notion of stronger and weaker comes from predicate logic. A predicate P is stronger than a predicate Q (and Q is weaker than P) if the set of states that match P is a strict subset of those that match Q. Since a specification is a predicate over implementations, making a specification stronger means shrinking the set of implementations that satisfy it. It may help to think of “stronger” as more constrained, or tighter, while “weaker” is less constrained, looser.

Note that it is also possible for predicates P and Q to be incomparable – neither stronger nor weaker – if neither is a subset of the other.

To decide whether one specification is stronger or weaker than another, we compare the strengths of their preconditions and postconditions. A precondition is a predicate over the state of the input, so making a precondition stronger means shrinking the set of legal inputs. Similarly, a postcondition is a predicate over the state of the output, so a stronger postcondition shrinks the set of allowed outputs and effects.

A specification S2 is stronger than or equal to a specification S1 if and only if

If this is the case, then an implementation that satisfies S2 can be used to satisfy S1 as well, and it’s safe to replace S1 with S2 in your program.

This rule embodies several ideas. It tells you that you can always weaken the precondition, because placing fewer demands on a client will never upset them. And you can always strengthen the postcondition, which means making more promises to the client.

For example, this spec for find:

function findExactlyOne(a: Array<number>, val: number): number- requires:

valoccurs exactly once ina- effects:

- returns index

isuch thata[i]=val

function findOneOrMore,AnyIndex(a: Array<number>, val: number): number- requires:

valoccurs at least once ina- effects:

- returns index

isuch thata[i]=val

which is a stronger spec because it has a weaker precondition — it constrains the inputs less. This in turn can be replaced with:

function findOneOrMore,FirstIndex(a: Array<number>, val: number): number- requires:

valoccurs at least once ina- effects:

- returns lowest index

isuch thata[i]=val

which is a stronger spec because it has a stronger postcondition — it constrains the output more.

What about this specification:

function findCanBeMissing(a: Array<number>, val: number): number- requires:

- nothing

- effects:

- returns index

isuch thata[i]=val, or -1 if no suchi

Let’s compare to findOneOrMore,FirstIndex.

Again the precondition is weaker, but for inputs that satisfy findOneOrMore,FirstIndex’s precondition, the postcondition is also weaker: the requirement for lowest index has been removed.

Neither of these two specifications is stronger than the other: they are incomparable.

We’ll come back to findCanBeMissing in the exercises and compare it to our other specifications.

Diagramming specifications

Imagine (very abstractly) the space of all possible TypeScript functions.

Each point in this space represents a function implementation.

First we’ll diagram findFirst and findLast defined above.

Look back at the code and see that findFirst and findLast are not specs.

They are implementations, with function bodies that implement their actual behavior.

So we denote them as points in the space.

A specification defines a region in the space of all possible implementations. A given implementation either behaves according to the spec, satisfying the precondition-implies-postcondition contract (it is inside the region), or it does not (outside the region).

Both findFirst and findLast satisfy findOneOrMore,AnyIndex, so they are inside the region defined by that spec.

We can imagine clients looking in on this space: the specification acts as a firewall.

Implementors have the freedom to move around inside the spec, changing their code without fear of upsetting a client. This is crucial in order for the implementor to be able to improve the performance of their algorithm, the clarity of their code, or to change their approach when they discover a bug, etc.

Clients don’t know which implementation they will get. They must respect the spec, but also have the freedom to change how they’re using the implementation without fear that it will suddenly break.

How will similar specifications relate to one another? Suppose we start with specification S1 and use it to create a new specification S2.

If S2 is stronger than S1, how will these specs appear in our diagram?

Let’s start by strengthening the postcondition. If S2’s postcondition is now stronger than S1’s postcondition, then S2 is the stronger specification.

Think about what strengthening the postcondition means for implementors: it means they have less freedom, the requirements on their output are stronger. Perhaps they previously satisfied

findOneOrMore,AnyIndexby returning any indexi, but now the spec demands the lowest indexi. So there are now implementations insidefindOneOrMore,AnyIndexbut outsidefindOneOrMore,FirstIndex.Could there be implementations inside

findOneOrMore,FirstIndexbut outsidefindOneOrMore,AnyIndex? No. All of those implementations satisfy a stronger postcondition than whatfindOneOrMore,AnyIndexdemands.Think through what happens if we weaken the precondition, which will again make S2 a stronger specification. Implementations will have to handle new inputs that were previously excluded by the spec. If they behaved badly on those inputs before, we wouldn’t have noticed, but now their bad behavior is exposed.

We see that when S2 is stronger than S1, it defines a smaller region in this diagram; a weaker specification, on the other hand, defines a larger region.

In our figure, since findLast iterates from the end of the array arr, it does not satisfy findOneOrMore,FirstIndex and is outside that region.

Another specification S3 that is neither stronger nor weaker than S1 might overlap (such that there exist implementations that satisfy only S1, only S3, and both S1 and S3) or might be disjoint. In both cases, S1 and S3 are incomparable.

reading exercises

Here are the find specifications again:

function findExactlyOne(a: Array<number>, val: number): number- requires:

valoccurs exactly once ina- effects:

- returns index

isuch thata[i]=val

function findOneOrMore,AnyIndex(a: Array<number>, val: number): number- requires:

valoccurs at least once ina- effects:

- returns index

isuch thata[i]=val

function findOneOrMore,FirstIndex(a: Array<number>, val: number): number- requires:

valoccurs at least once ina- effects:

- returns lowest index

isuch thata[i]=val

function findCanBeMissing(a: Array<number>, val: number): number- requires:

- nothing

- effects:

- returns index

isuch thata[i]=val, or -1 if no suchi

We already know that findOneOrMore,FirstIndex is stronger than findOneOrMore,AnyIndex, which is stronger than findExactlyOne.

(missing explanation)

Designing good specifications

What makes a good function? Designing a function means primarily writing a specification.

About the form of the specification: it should obviously be succinct, clear, and well-structured, so that it’s easy to read.

The content of the specification, however, is harder to prescribe. There are no infallible rules, but there are some useful guidelines.

The specification should be coherent

A coherent spec makes sense to its clients as a single, complete unit. The spec shouldn’t have lots of different cases. Long argument lists, boolean flags that enable or disable behavior, and intricate logic, are all signs of trouble. Consider this specification:

Is this a well-designed function? Probably not: it’s incoherent, since it does several things (finding in two arrays and summing the indexes) that are not really related. It would be better to split it into two separate functions, one that finds the indexes, and the other that sums them.

Here’s another example, the countLongWords function from Code Review:

let LONG_WORD_LENGTH: number = 5;

let longestWord: string;

/**

* Update longestWord to be the longest element of words, and print

* the number of elements with length > LONG_WORD_LENGTH to the console.

* @param text text to search for long words

*/

function countLongWords(text: string): voidIn addition to terrible use of global variables, printing instead of returning, and mentioning a local variable (words), the specification is not coherent.

It does two different things: counting words and finding the longest word.

Separating those two responsibilities into two different functions will make them simpler (easy to understand) and more useful in other contexts (ready for change).

The results of a call should be informative

Consider the specification of a function that puts a value in a map, where keys are of some type K and values are of some type V:

Note that the precondition explicitly permits null values in the map.

But the postcondition uses null as a special return value for a missing key.

This means that if null is returned, you can’t tell whether the key was not bound previously, or whether it was in fact bound to null.

This is not a very good design, because the return value is useless unless you know for sure that you didn’t insert nulls.

If we can’t avoid allowing null in the precondition, we should use a better special result in the postcondition in the case where key was not previously mapped.

The specification should be strong enough

Of course the spec should give clients a strong enough guarantee in the general case — it needs to satisfy their basic requirements. We must use extra care when specifying the special cases, to make sure they don’t undermine what would otherwise be a useful function.

For example, consider this spec:

function addAll(arr1: Array<T>, arr2: Array<T>): voidThis spec is written in an inappropriately operational style, but let’s focus on a different problem.

This spec is stronger than one that doesn’t mention null elements at all (because then nulls would be implicitly disallowed).

But it’s not strong enough to be useful to a client, because it allows an arbitrary amount of mutation to happen before the TypeError exception is thrown.

If the exception is caught by the client, the client is left wondering which elements of arr2 actually made it to arr1.

We could improve the specification by strengthening it further, e.g.:

The specification should also be weak enough

Consider this specification for a function that opens a file:

This is a bad specification. It lacks important details: is the file opened for reading or writing? Does it already exist or is it created? And it’s too strong, since there’s no way it can guarantee to open a file. The process in which it runs may lack permission to open a file, or there might be some problem with the file system beyond the control of the program. Instead, the specification should say something much weaker: that it attempts to open a file, and if it succeeds, the file has certain properties.

Precondition or postcondition?

Another design issue is whether to use a precondition, and if so, whether the function code should attempt to make sure the precondition has been met before proceeding. In fact, the most common use of preconditions is to demand a property precisely because it would be hard or expensive for the function to check it.

As mentioned above, a non-trivial precondition inconveniences clients, because they have to ensure that they don’t call the function in a bad state (that violates the precondition); if they do, there is no predictable way to recover from the error. So users of functions don’t like preconditions. That’s why many JavaScript library functions, for example, tend to specify as a postcondition that they throw exceptions when arguments are inappropriate. This approach makes it easier to find the bug or incorrect assumption in the caller code that led to passing bad arguments.

In general, it’s better to fail fast, as close as possible to the site of the bug, rather than let bad values propagate through a program far from their original cause.

Even if, for example, atan(y, x) requires as a precondition that its input not be (0,0), it would still be helpful for it to check for that mistake and throw an exception with a clear error message, rather than returning a garbage value or a misleading exception.

Sometimes, it’s not feasible to check a condition without making a function unacceptably slow, and a precondition is often necessary in this case.

If we wanted to implement the find function using binary search, we would have to require as a precondition that the array be sorted.

Forcing the function to actually check that the array is sorted would defeat the entire purpose of the binary search: to obtain a result in logarithmic and not linear time.

The decision of whether to use a precondition is an engineering judgment. The key factors are the cost of the check (in writing and executing code), and the scope of the function. If the function is only called locally, inside one module, the precondition can be discharged by carefully checking all the sites that call the method. But if the function is exported or public, so that it can be called anywhere in a program and used by other developers, it would be less wise to use a precondition. Instead, like the JavaScript library, you should throw an exception as a postcondition.

reading exercises

function secondToLastIndexOf(arr: Array<number>, val: number): number- requires:

valappears inarran odd number of times- effects:

- returns the 2nd-largest

isuch thatarr[i]=val

(missing explanation)

function secondToLastIndexOf(arr: Array<number>, val: number): number- requires:

valappears inarran odd number of times- effects:

- returns the 2nd-largest

isuch thatarr[i]=val

Consider the following test cases for secondToLastIndexOf.

Say if each one is already valid; or if not, what changes are necessary to make it valid:

(missing explanation)

(missing explanation)

(missing explanation)

(missing explanation)

Summary

A specification acts as a crucial firewall between implementor and client — both between people (or the same person at different times) and between code. As we saw last time, it makes separate development possible: the client is free to write code that uses a module without seeing its source code, and the implementor is free to write the implementation code without knowing how it will be used.

Declarative specifications are the most useful in practice. Preconditions (which weaken the specification) make life harder for the client, but applied judiciously they are a vital tool in the software designer’s repertoire, allowing the implementor to make necessary assumptions.

As always, our goal is to design specifications that make our software:

Safe from bugs. Without specifications, even the tiniest change to any part of our program could be the tipped domino that knocks the whole thing over. Well-structured, coherent specifications minimize misunderstandings and maximize our ability to write correct code with the help of static checking, careful reasoning, testing, and code review.

Easy to understand. A well-written declarative specification means the client doesn’t have to read or understand the code. You’ve probably never read the code for, say, Python

dict.update, and doing so isn’t nearly as useful to the Python programmer as reading the declarative spec.Ready for change. An appropriately weak specification gives freedom to the implementor, and an appropriately strong specification gives freedom to the client. We can even change the specs themselves, without having to revisit every place they’re used, as long as we’re only strengthening them: weakening preconditions and strengthening postconditions.