Hands-on 6: Understanding TCP and tcpdumpComplete the following hands-on assignment. Submit your solutions using the online submission site by 11:59pm on March 15th. SetupWe recommend, but do not require, that you perform this assignment on Athena. Please note that the TAs cannot guarantee tech support if you do not use an Athena workstation. Before you begin the assignment, please verify that tcpdump is installed. Most athena workstations (and linux machines, in general) should have tcpdump installed by default. If you get the error 'tcpdump: Command not found.', on an athena machine, run: 1. Understanding tcpdumpIn this assignment you will understand how TCP works using tcpdump. To begin with, download the tcpdump log file from here. You can also download it on any linux machine using: For this trace, we used a program that transmits a file from a machine called willow to a machine called maple over a TCP connection. We ran the tcpdump tool on the sender, willow, to log both the departing data packets and the received acknowledgments (ACKs). The file tcpdump.dat is a binary file which contains a log of all the TCP packets for the above TCP connection. The file is not human-readable. To parse the file, you can use tcpdump. For more information on tcpdump, you can look at: To understand the log file in a human-readable format, run: Now open outfile.txt on your preferred text editor. The output has several lines listing packets sent from willow to maple, and the ACKs from maple to willow. For example: Denotes a packet sent from willow to maple. The time stamp 00:34:41.474225 denotes the time at which the packet was transmitted by willow. TCP uses sequence numbers to keep track of how much data it has sent. For teaching purposes, we often associated one sequence number with each packet (packet 1, packet 2, etc.). In reality, there is one sequence number per byte of data. The above packet has a sequence number 1473:2921, indicating that it contains all bytes from byte #1473 to byte #2920 (= 2921 - 1) in the stream, which is a total of 1448 bytes. (Note: There may be very minor variations in the format of the output of tcpdump depending on the version of tcpdump on your machine.) Once maple receives the packet, assuming that it has received all previous packets as well, it sends an acknowledgment (ACK): Again, for teaching purposes, we typically talk about an ACK reflecting the corresponding packet's sequence number. In reality, the ACK reflects the next byte that the receiver expects. The above ACK indicates that maple has received all bytes from byte #0 to byte #2920. The next byte that maple expects is byte #2921. The time stamp 00:34:41.482047, denotes the time at which the ACK was received by willow.

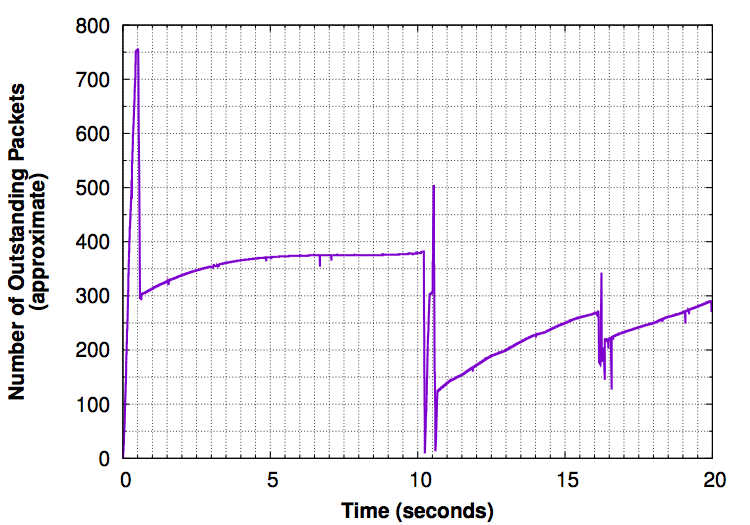

2. Congestion ControlFor the second part of the assignment, we ran a TCP connection between two different machines at MIT. These machines used a version of TCP known as TCP CUBIC. TCP CUBIC takes a similar approach to congestion control as the one you learned in lecture: senders increase their window until they see a loss, and then backoff. The only difference is in the increase function used to grow the window size. (You're welcome to dive into the details of TCP CUBIC at your own leisure, but to complete the hands-on, you do not need to know anything else about it.) Below, we have plotted the (approximate) number of outstanding packets in this connection vs. time. All of the following questions refer to the portion of the connection shown in the plot. You'll notice that the plot has some major trends, but exhibits small window-decreases in few places—e.g., between 6.5s and 7s and around 19s. Those small decreases are an artifact of how we measured the number of outstanding packets; you can ignore them. The questions below are concerned with the larger trends.

|