-

Contrary to previous city typologies, which were understood in terms of national economic prosperity and degrees of industrialization, a crucial distinguishing feature of globalizing cities is the degree to which large informal sectors flourish and accelerate public insecurity.

-

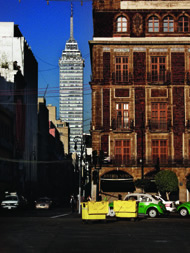

Changes in the built form of Mexico City illuminate the “competing globalizations” that increasingly operate in today’s cities.

-

The root cause of growing insecurity is social, spatial, and economic developments of the past and how they locate themselves in the present era of globalization.

Introduction

As anyone who has recently traveled to China, India, Brazil, or Mexico knows, the largest cities of the developing world are no longer what they used to be. Far from the picture of resource-poor, dilapidated, and under-built backwaters of poverty that has long dominated the perception of the global south, cities like Shanghai, Mumbai, Sao Paolo, and Mexico City now host gleaming skyscrapers and applications of some of the newest urban and infrastructural technologies. Conversely, many of the prosperous cities of the developed world—for example, New York and London—now exhibit accelerating social and economic polarization, giving them indices of inequality that have long been associated with the developing world. Together, these patterns suggest a convergence in land uses, built forms, and social problems in cities all over the world—ranging from upscale real estate developments and high-end global business clusters to social and economic polarization to culturally and globally hybrid work forces, all of which operate in the context of extreme urban concentration and sprawl. Many scholars have traced these newfound patterns of urban development to globalization. Globalization not only brings rapid and accelerating flows of global capital in search of new forms of investment, but also leads the shift from manufacturing to service and information economies. The question, however, is as follows: Are we really seeing a commonality of urban patterns worldwide, particularly among the major cities of the world? Or do these visual commonalities hide, or co-exist with, other less obvious differences? If the latter, what are those differences, and what challenges do they pose for international urban development planners and practitioners?

To ask these questions is not merely to call attention to the physical and social transformation of cities in the contemporary epoch. Doing so also suggests an analytical concern with understanding the best ways to categorize world cities and diagnose their key developmental challenges. This paper argues that, contrary to previous city typologies, a crucial distinguishing feature of globalizing cities is the degree to which large informal sectors flourish and accelerate public insecurity.

Prior to globalization, most typologies for world cities grew out of an understanding of the larger economic context in which urban locales were situated, understood in terms of national economic prosperity and degrees of industrialization. These notions were captured in the lexicon of “developing” versus “developed” country cities, or cities of the global “north” versus “south.” The primary cities of developed countries were understood to host more investments in the built environment, higher-end services and commerce, more developed property markets, higher rates of home ownership, and less poverty. Cities in developing countries were seen as lacking in basic urban infrastructure, frequently leading to their characterization as “over-urbanized,” especially in comparison to those of the developed world. They were also overcrowded and poor; informality in housing and employment was the norm, and industrial factories dominated prime urban lands.

Political context was occasionally used as a reference point for city typology, albeit often in tandem with the aforementioned economic characteristics. Democratic countries, especially those in which market capitalism flourished and the state was responsive to the productive classes as much as the people, were seen as hosting different urban patterns than socialist, communist, or authoritarian countries in which the “command” efforts of the state trumped market logic. Likewise, cities in colonial countries, where mercantile relations linked ruler and ruled, were also seen as hosting different urban forms, reflecting either an outflow or inflow of capital and investments. In both cases, political regime types were associated with certain urban land use patterns, ranging from the absence of commercially-based downtowns to the emergence of massive public housing blocs to limited investments in non-productive urban infrastructure, to name but a few. While these urban differences were sometimes attributed to national “character,” social history, or cultural repertoires, a more likely explanation was the degree of market versus state balance in urban policymaking, a distinction that itself was correlated to the type of political regime.

Within countries of the same developmental status or political regime-type, a similar logic was used to differentiate among locales. Cities were frequently defined in terms of their position in the political system (such as capital versus other cities), in terms of their functional role in the domestic economy (such as industrial, commercial, service, or agricultural centers), or in terms of their cultural histories. The first set of explanations was used to show why Washington, D.C. differed from New York or Monterrey differed from Mexico City, while the second and third explanations could account for differences between New York City and New Orleans, Mexico City and Veracruz, or Rome and Bari, to name but a few examples.

In the contemporary era, however, as global capitalism brings ever more cities into its orbit, such territorially-based cultural, economic, and political regime distinctions have started to break down. Many cities share common economic features and similarly built urban environments. The stark distinctions between producer, consumer, investor, and exchange roles in both the domestic and global economy have become blurred, as have the distinctions between flows of capital, building styles and patterns of urban land use within and between rich and poor countries around the world. The question thus emerges as to what urban typologies and categorizations can best capture these contemporary local, national, and global dynamics. Will new typologies undermine or co-exist with old ways of classifying cities, either in terms of methodological building blocks or classificatory outcomes, how or why, and with what implications for urban theory and practice?

I seek to answer these questions using the case of Mexico City as a reference point. By exploring the recent changes in Mexico City’s form, function, and character as a result of globalization and other recent economic and political changes, and by comparing Mexico City’s current patterns to those that are now evident in cities of Europe, the United States, East Asia, and other urban locations worldwide, I seek to arrive at a new typology for characterizing what is similar and what is different among world cities in the contemporary global era. Among the methodological strategies that are used to arrive at this alternative typology are close examinations of (i) the new political, social, and economic actors that globalization has produced, (ii) the ways in which these new actors change the daily life and built environment of the city, and (iii) how and why these actors and activities are distributed across all “global” cities. The key urban problems and conflicts that emerge as a result of this new constellation of forces and conditions are also identified as central in the definition of alternative city types.

This paper argues that a key feature that distinguishes world cities from each other, despite the shared architectural and investment profile of the urban built environment within many of them, is the degree of accelerating public insecurity and the deteriorating rule of law. It argues that such problems can exist even in cities that on the visual or architectural surface seem eminently “modern” and globalized. It further claims that the emergence of a large, globally-linked informal sector can exacerbate problems of public insecurity by generating new forms of conflict and tension, which I will characterize as “competing globalizations.” I define these competing globalizations as the struggle between two “economies,” or divergent networks of economic forces that draw their economic strength from entirely different complexes of global actors and investors, yet whose uneasy co-existence in a delimited physical space turns them into ruthless competitors to control land use and the character of downtown. The public insecurity that results from these conflicts produces social, spatial, and economic fragmentation in ways that drive the cycle of tensions over globalization, and further distinguish insecure from secure cities. This paper ends with an assessment of why some global cities are more prone to urban insecurity and lawlessness than others.

Before turning to more discussion, a few words are in order about why this methodological exercise matters. One cannot understand international development these days, and the longer-term prospects for prosperity in a given nation, without understanding what is happening in key global cities, which serve as the command and control functions of global capital. To understand global cities, in turn, requires an appreciation of changes within each of these cities, and an understanding of whether and how the attributes that are associated with certain global cities can affect long-term urban sustainability. Undertaking this task not only entails an examination of whether recent changes make these cities better places in which to live, but also efforts to identify and reinforce (or eliminate) those conditions that facilitate (or impede) long-term prosperity. To do so, it is important to understand the large sociological dynamics that underlie urban trends, precisely because such knowledge gives us clues as to how and why social and economic trends might be changing in the world’s global cities—either for the better or the worse. Specifically, the exercise of generating new categorizations or typologies for contemporary global cities gives a short-hand method for understanding more general urban trends that may spread across divergent developmental states or economic conditions, which in turn can serve as a way to examine the most pressing policy concerns and the most appropriate domains for development planning action.

Mexico City as a Case Study

As noted earlier, previous frames of reference for categorizing cities frequently relied on national-level characterizations of political and economic “progress.” The most challenged cities were in “late industrializing” countries where democracy remained elusive and poverty persisted. As globalization and liberalization began accelerating over the last several decades, many of these countries faced the promise of fundamental change, both urban and national. Mexico is a good case in point. Newfound prospects for democracy and the promise of sustained economic development that came with global support for liberalization (up to and including the 1994 signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement) produced a spurt of enthusiasm among investors and public officials who were eager to transform that country’s capital into a global city. The idea was that through investments in urban infrastructure and new urban mega-projects, the world’s leading investors would feel comfortable enough to locate global corporate headquarters in Mexico City, and that such urban developments would generate sufficient capital flows to spur new patterns of national investment (and vice-versa). Changes in the built form of Mexico City appear to reflect these global trends.

Over the past 15 years, Mexico City’s urban economy and downtown land uses have transformed along the lines that global cities literature would predict. These evolutions are apparent in the recent “rescue” of downtown Mexico City, accomplished through the development of a new, upscale tourist, corporate, and residential complex. Night life, commerce, and youth activities are on the upswing in ways that would have been unthinkable a mere five years ago, and the ever more modern building projects that dot the skyline make this city a cosmopolitan rival to other affluent, globally connected cities around the world. Mexico City also shows its new face in an area that is ten kilometers from downtown, called Santa Fe. Considered a major new “cluster” development that is intended to attract a wide array of global firms, it is filled with high-rise after high-rise that are conceived within the most exotic and sophisticated architectural styles imaginable. On the surface, its buildings resemble those that dot the skylines of London, New York, Miami, and Tokyo, and the degree of concentration of residential and corporate high-rises evokes the feel of cities like Singapore, Shanghai, and Hong Kong. These projects have increased the social and political profile of a new cadre of “globalizing elites,” not just corporate executives of both foreign and national origin, but also a smattering of hotshot architects who possess name recognition and global visibility. Governing officials in the metropolitan area, while hardly new actors, once again stand at the forefront of the public eye as their willingness to invest in new infrastructure (roadways, fiber optics, bridges, security technologies, and so forth) has generated considerable political discussion.

Nonetheless, these are not the only new actors in the contemporary global city. Also on the rise in terms of social visibility and impact on land use are informal sector workers, many of whom are involved in illicit activities. Many of these people have had their economic livelihood disrupted—and their downtown-based activities displaced—by the new urban mega-projects. As a result, the overall urban ambiance is not as idyllic as the iconic architectural styles and new corporate or residential buildings would suggest. Nor is the quality of life in Mexico City the same as it is in the global cities of Europe and the United States that it visually seeks to resemble. Over the last several years, problems of violence, crime, and insecurity have emerged with a vengeance in many parts of the city. They were first most visible downtown, but they have gradually migrated to more peripheral parts of the metropolitan area, as the perpetrators have been slowly but steadily pushed out of downtown. Extreme public insecurity and random violence wrack most neighborhoods. Of the newly redeveloped areas, only Santa Fe seems to have escaped the worst of the daily problems of insecurity, but this outcome prevailed only because this area has been designed as an urban fortress, with technology, gating, tunnels and other architectural innovations that limit the free flow of people and goods. Private security guards roam the streets with a frequency that has no parallel in the city’s past, and in ways that can be readily replicated in other “globalizing” parts of the city, especially downtown. Even with surveillance cameras and security guards, the problems of insecurity continue to accelerate.

The massive property development projects downtown, most of which started in 2001 and 2002, have stalled considerably because the security situation has not improved enough for most middle- and upper-income residents to move to the redeveloped parts of the city, and because many low-income residents insist on remaining downtown. With many low-income residents and small commercial firms unwilling to move away from this strategic central location (which continues to serve them well in an expanding metropolis of 20 million people), developers may have hit a glass ceiling in terms of the revenue to be generated through investment in an upscale downtown property market. Such constraints have further fueled the development of gated “cluster” areas like Santa Fe, which exists almost as “another world.”

But again, the rest of the city is not nearly so protected, so security conditions almost everywhere else are far more fragile. Most streets remain dangerous, and daily excursions from home to work remain volatile, with murders and assassinations relatively unchecked, and with Mexico City police remaining fearful at times of entering certain neighborhoods. A steady inflow of street vendors and other under-employed service workers fills most of the city’s streets beyond capacity, reproducing the old-style informality and a mix of rich and poor that is more commonly associated with past epochs and “traditional” third world cities than with a modern, globalizing metropolis. In short, the problems of insecurity exist alongside the new urban mega-projects and infrastructure developments that global capitalists have spurred to catapult the city into yet another world-recognized global city.

“Competing Globalizations”

What makes this state of affairs particularly intriguing, if not somewhat paradoxical, is the fact that many of the forces that are responsible for the conditions of crime, violence, and insecurity have themselves been empowered through globalization, albeit through a very different network of global flows and activities than that which has brought the downtown and Santa Fe property development forces into the picture. Even in the face of the Alameda project’s recent approval, one could say that continued conflict over Mexico City’s downtown development owes to “competing globalizations.”

We could identify these two distinct global networks as “liberal” and “illiberal” (rather than legal and illegal). The former are defined as “liberal” since they appear “legitimate” in the eyes of economic liberalization’s proponents; they constitute a legally accountable network of corporate and property investors who operate in a world of regulations, property rights, and formal contract law. The latter are defined as “illiberal” because they are considered “illegitimate” partakers of the global economy; they constitute networks of illicit (and often small-scale) investors whose global supply chain revolves around black market, undercover, clandestine, or violence-prone activities where the rule of law remains elusive (that is, those that involve the marketing and global distribution of drugs, guns, and other forms of contraband). They assert their political and economic power through illicit rather than licit networks of trade and distribution, and they sustain their activities despite the absence of formal property rights over the spaces that they control and the goods that they trade.

Complicating matters further, these “competing globalizers” have divergent spatial aims and colliding downtown development visions. The “liberal” globalizers desire an upscale renovation of downtown with open spaces and pristine architectural environments for other global investors, tourists, and upscale consumers. The “illiberal” globalizers thrive in the dilapidated, informal, and inaccessible back alleys and streets where their clandestine activities can remain hidden from view, and where police often fear to tread. This dichotomy implies that liberal and illiberal global forces frequently clash over the desired character and built environment of downtown; this conflict produces the violence and insecurity that now destabilize Mexico City. It is further worth noting that these struggles are as much about control over space and the nature of the city as they are about the direction, or globalization, of the economy. Stated differently, they raise a question of whose global network is going to prevail in what physical space, with the main protagonists in the struggle being liberal and illiberal forces, both tied to globalization in some way. To the extent that these struggles over space are linked to economic livelihood and profitability, the stakes are quite high. Because the conflict involves “illiberal” forces who shun the rule of law, it can be quite violent and dangerous; urban politics does not offer any easy remedy to such battles.

For all of these reasons, Mexico City now experiences ongoing conflict between “competing globalizers.” These battles play themselves out in the streets of the city and on the terrain of security as much as they do in formal political deliberation and dialogue. This conflict over the city’s “global character” continues to drive violence and insecurity, pushing this city on a downward spiral towards near anarchy—and authoritarian attempts to control it—in the institutions and practices of everyday urbanism.

The Alameda area is already protected by a special police force, high-tech surveillance cameras, and private security guards, even as it remains surrounded by dilapidated areas that play host to informal sector activities. Further efforts of this nature will likely be used to create mobility barriers between the upscale, redeveloped parts of the Alameda and the surrounding area of Tepito. As a result, Mexico City could face even greater socioeconomic and spatial polarization (both within Tepito and between it and other key downtown locations). Such spatial outcomes may sustain the theoretical propositions that are advanced in the urban globalization literature, and suggest a certain convergence in land use patterns across global cities. However, they also suggest an extreme form of social and spatial polarization that is mediated by violence that we would not expect to see in other global cities like London, Tokyo, and Singapore. Complicating matters, the short-term implications of this pattern may undermine the long-term path towards convergence. Extreme polarization and violence will set clear limits on further upscale property development and circumvent any movement towards global “convergence” in downtown urban land uses across the Mexico City metropolitan area, as well as between Mexico City and other global cities.

Seeking the Origins of the New Global Urban Disorder: History, Economics, and Politics

How can we explain this state of affairs, featuring high levels of violence that permeate upscale global investment centers like Mexico City, and ongoing tensions over domination of space between “competing globalizers?” One answer is that the growing problems of urban violence and insecurity are traceable to the path-dependent consequences of past decisions about economic development, governance, state formation, and industrialization. That is, where a city “comes from”—in terms of its history and with respect to the larger national development context in which it emerged—limits what type of contemporary global city it can become.

In prior decades, governments in countries of the global south like Mexico were able to pursue industrialization projects because they counted on strong and/or authoritarian states that developed strong policing and military apparatuses to control labor and consolidate state power vis-à-vis agrarian interests on behalf of an emergent industrial class of manufacturers. These legacies empowered the late developmental state’s coercive apparatuses so as to undermine the judicial system and facilitate corruption and impunity within the ranks of the police and the military (if not the state itself). Over time, such abuses of power led to demands for democratization. Even so, regime democratization did not eliminate all prior institutions and practices. Even after democratic transition, many late developers still face the political and economic future with the same old coercive networks intact, especially in the rank-and-file segments of the police and military.

After years of working without effective institutional constraints—as part of the bargain with the elite to police the nation’s political and economic “enemies,” be they laborers, socialists and communists, street vendors, or agrarian rebels, so as to guarantee state power and economic progress—the coercive arms of the late developmental state became well ensconced in a networked world of impunity, corruption, and crime. Their power and longevity sustained illegal practices in the state and in civil society, leading to a steady erosion of the rule of law. Such is the institutional legacy bequeathed to many countries of the global south, and democracy has done little to reverse it.

Such is not to say that all cities of the late developing world are saddled with similar legacies, or that, even if they were, they would all face identical problems of insecurity. Nor is such to suggest that the police and military are the only sources of violence and contemporary disorder. Many countries did effectively purge their old police during the democratic transition, with South Africa being one of the few to do so successfully. Other late developers, like India, have been democratic for much longer, and their main cities do not confront the legacies of police and military coercion. Still others, such as the East Asian tigers, have hosted authoritarian regimes but have eluded much of the violence and insecurity that plague their late developmental counterparts. Thus, it is important to recognize that the economic legacies of late development are also important in accounting for patterns and locations of problems of insecurity in so many countries of the global south. There are two other key factors that are linked to prior economic development models: the extent of informality and the extent of income and social polarization. Both trace their roots to past patterns of political and economic development.

In prior decades, most late developers tread a very rocky economic road in which formal employment in industry paled in comparison to informal employment in small-scale commerce and other petty services, with government employment generally taking up the slack. These sectoral imbalances were all too often ignored in much of the sociological work on late development, which focused primarily on the key drivers of production (capital, labor, and the state) and the big-ticket strategies of growth (industrialization, either import-substitution industrialization [ISI] or export-oriented industrialization [EOI]), while ignoring the diversity of class identities and sectoral composition of economic activities that sustained late development. These sectoral patterns have always been problematic, but globalization and liberalization on a world scale have exacerbated them. With the neoliberal turn bringing a downsized state, and with expectations of greater global competitiveness driving many countries to reduce traditional sources of manufacturing and agriculture, these sectoral imbalances—and the attendant growth of services and informality—have become more extreme.

Part of the problem is that the two main sources of economic growth in today’s world—export-led industrialization and the development of the high-end financial services that are linked to real estate development and the information economy—exacerbate social and income polarity, especially in cities. In both social and spatial terms, the polarization is extreme, and these patterns lie at the root of the current problems of urban violence and insecurity. The issue, again, is not merely income inequality. Polarization also raises the question of what employment sectors remain open as the largest source of work opportunities. With fewer available job prospects in industrial manufacturing and many new employment opportunities beyond the educational reach of those who have been laid off from factories in the drive to develop a more globally competitive information technology service sector, more citizens than ever before are being thrown into the informal sector. Such employment, which barely meets subsistence needs for those who are stuck within it, is becoming more “illicit” as protectionist barriers drop, as fewer domestic goods for sale are produced, and as the globalization of the illegal goods trade picks up the slack. In many cities of the global south, mafias involved in all forms of illegal activities, ranging from drug and weapons trafficking to the sale of knock-off designer products and CDs, are calling the shots. These forces often take on the functionally equivalent role of mini-states by monopolizing the means of violence and providing protection and territorial governance in exchange for allegiance.

For those of us who want to understand the impact of these large-scale political and economic transformations within the context of urban insecurity, we need to understand the spatial context of these developments. Specifically, much of the current informal employment is physically and sectorally situated within an illicit world of violence and impunity, not just because of the sheer illegality of many of the goods that are traded, but also because big-money trade in drugs, guns, and other contraband products generally necessitates its own “armed forces” for protection and contract enforcement. The result is often the development of further clandestine connections between local police, mafias, and the informal sector, as well as the isolation of certain territorial areas as locations for these activities. This illicit network of reciprocities, and the territorial concentration of dangerous illegal activities in locations that function as independent fiefdoms, outside state control, further drive the problems of impunity, insecurity, and violence in cities where these mafia reside. The most dangerous areas can be found in large cities where global supply chains find the greatest concentration of producers, consumers, and distributors. The purveyors of these goods often locate in old central business districts where local chambers of commerce face a declining manufacturing base and are especially desperate to attract high-end corporate investors and financial services. This need leads to a physical clash of forces and development models—and growing problems of insecurity—that can thwart the developmental aims of aspiring global cities as well as those of the national investor class that seeks to generate global capital and visibility.

Typologies for a New Global Era: Secure and Insecure Cities

Mexico City may have its own political, spatial, and historical peculiarities that have made its built environment particularly contested, complex, and violent. Even so, it is not alone. Many other cities share these legacies, and they tend to face chronic problems of violence and insecurity. Indeed, the persistence and growth of an informal sector throughout periods of industrialization, the spatial contiguity of various social classes, the vibrancy of commercial and downtown life, the politics of urban clientelism, and the expanding networks of illegal activities that hovered in the background of the Mexico City story, are also characteristic of other developing-country cities that now wish to achieve global preeminence: Johannesburg, Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro, and Manilla, among others.

Still, these problems cannot be understood as affecting all cities of the global south; nor are they entirely absent in every city of the global north, even if the pervasiveness of the problem may not be as extreme. Put another way, not all of the cities of the south are becoming like those of the north, even though some cities of the north share characteristics with their southern counterparts. The root cause of growing insecurity is social, spatial, and economic developments of the past and how they locate themselves in the present era of globalization. There are certain cities in the “industrialized north” that share many features of those in the global south, just as there are cities in the late-industrializing world that have transcended those constraints. In the late-developing world, for example, it is striking that many of the cities of East Asia seem to have avoided the descent into violent chaos and the clash of development models that plague their Latin American counterparts. Why is such the case?

First, burgeoning urban informality is not a serious problem across all cities of the global south. Massive employment in export-led industrial sectors arrived early on in East Asian countries, thereby allowing them to avoid the disruptive plant closings and attendant unemployment that came in the abrupt shift from ISI to EOI in most of the rest of the global south. Just as important, these are the same late developers that remained rural for much longer and in which high rates of urbanization came relatively late. For another, even as they pursued export-led industrialization, these countries also fostered small-scale commercial and industrial production, and prioritized employment over capital intensity in commercial and industrial production, be it domestic or export-led. Thus, their economies remain a vibrant source of both employment and growth. This combination of “historical advantages” set a clear cap on the growth of the informal sector.

Paradoxically, moreover, these very same historical advantages have given certain countries like South Korea and China a leading role as suppliers in the global network of (manufactured) contraband consumer goods, many of which are found on the streets of troubled cities like Rio de Janeiro and Mexico City. Thus, we see a small but leading group of “late” developers reaping the benefits of export-led industrialization once again, but doing so at the cost of rising illegality and violence among its less fortunate counterparts, whose problems stem from being on the wrong end of the same global supply chain. The result is a “categorical” split within the so-called “global south” where the relevant analytical distinction is not so much the degree of formal democracy or the extent of global integration and global investment in the built environment, but rather, the extent of violence, insecurity, illegality, and lawlessness. Stated differently, global cities differ in the degrees of their security and insecurity, despite sharing many similar built environmental features, but these differences do not map neatly into a north-south division. Rather, they are more directly correlated to particular urban and national development histories, which themselves must be examined with something more than a northern and southern, or early versus late developmental, lens.

Let us take this logic one step further, using it as a basis for developing a new framework for understanding similarities and differences in contemporary cities of the global north. Clearly, the problems of extreme violence, insecurity, and lawlessness that characterize so many Latin American and African cities—and that are related to histories of informality, occupational structure, income inequality, and national industrial development trajectories—are not evident in most major cities of the global north, among them Paris, Milan, Tokyo, and New York. Such is not to say, however, that they are absent, or that they are not materializing as a result of globalization. In the United States, Europe, and elsewhere in the advanced capitalist north, many secondary and tertiary cities grew with similar patterns of industrialization, demography, and urban form. Detroit is a good example in the United States. Little money was spent on upscale real estate development and downtown “modernization,” in contrast to the capital cities in the aforementioned countries. Employment centered on industrialization for a domestic market, and low-level commerce and services were the norm. In some instances, rural decline brought new migrants to cities in search of employment opportunities, a population pressure that translated into an inflated small-scale commercial and service sector, especially when their arrival coincided with a decline in the manufacturing sector. Many locales of southern Italy and certain Eastern European countries could also serve as good examples. To be sure, in most of the cities of the global north, even small ones, strong welfare state programs and commitment to employment prevented these conditions from devolving into the social polarization and intense informality that laid the basis for subsequent patterns of violence in certain cities of the global south. However, the current era of globalization may be changing that reality.

Given the political and economic restructuring of national economies in response to globalization, new actors and urban conditions emerge. The move from manufacturing and industrialization to high-end services and an information- or technology-based economy, evident in many parts of the advanced capitalist north as well as the “south,” has brought forth new investors and actors while displacing old ones who remain wedded to the industrial economy. Combined with the fact that many nation-states are pursuing a more neoliberal social policy, these economic and public policy shifts have placed constraints on full employment. The balance of industry and services is also shifting dramatically, driving investors to turn to real estate developments and other high-end urban projects even as it displaces factory workers who now seek new sources of work. While longstanding residents might not be pushed into low-end services or informality as a result of these larger macroeconomic shifts, new immigrants, who flow into these cities as a result of more fluid national borders and a globalizing labor force, gravitate to these low-skill areas of employment, where limited education and language deficiencies are not large barriers to entry. Further social and economic polarization may follow if they bring cultural traditions or longstanding customs of trading and informality, and if they are residentially isolated from the mainstream or socially excluded in ways that limit their physical, social, or cultural interaction with long-standing residents. In such environments, crime often flourishes.

Thus, alongside major global investors in real estate and iconic architecture who are seeking to jumpstart the urban economies of the post-industrial era, one might also see new foreign immigrants who are employed in services (formal and informal) and linked to trade in consumer goods, both legal and illegal, all of whom are operating in a context of increased crime. These patterns are starting to emerge in cities of the global north. When these new and old sets of forces clash socially, struggle for dominion over urban space, or find themselves on the opposite ends of urban privilege (in terms of income, access to basic needs provisions, and so forth), we may begin to see a version of the same problems that brought insecurity and violence in Mexico City and other historically similar urban locales of the global south.

Again, it is important not to over-emphasize the extent of similarity between the contemporary cities of the global south and north, in part because legal frameworks of urban action are so much more established in the latter than in the former, while it is an insufficient or deteriorating rule of law that has fueled the rise of insecurity and violence in cities of the late developing world like Mexico City. However, there are many urban locales in the democratic and affluent “north” where corruption, mafias, bribery, and other illicit practices also impact urban decision-making, suggesting that the distinction between law-abiding and lawless cities is better understood on a continuum.

Moreover, the overall sense of growing urban fear, and concerns about violence that have started to plague many cities of the global north in the last decade or so, have pushed residents to hire private security guards, develop gated communities, and use new technologies to protect themselves. These trends start to eat away at the institutional edifice of a rule of law because they shift responsibility for vigilance and maintaining public order to private hands. If security and, by extension, the “rule of law,” are available only to those who have the financial means to afford them, and if the whims of private individuals determine security actions and urban conditions, then the larger social contract that sustains the public guarantees of equitable legal treatment for all is in danger of rupture. Without a viable, publicly sanctioned, socially inclusive, and well-legitimized rule of law for the city, “mere” problems of violence can readily transform into widespread urban chaos and insecurity, especially if the socially, spatially, economically excluded newcomers turn to their own “rules” for governing urban life and livelihood.

What Can Be Done?

The problems that are described above are enormous, tracing their roots to macroeconomic shifts that are associated with globalizing economies, as well as their impact on urban social, economic, and spatial structures. They cannot be easily reversed. However, planners, architects, and sociologists must be prepared to think about how to envision a city that would not fall prey to these problems. Stated differently, they must think about how to make or keep cities secure, but without resorting only to “privatized” efforts to guarantee security. That is, they must be committed to developing truly public spaces that are open to all classes and cultures; they must be able to transcend the temptation to use gating or other techniques of spatial isolation to protect individuals; they must think about new ways to structure built form so as to emphasize social and economic integration rather than fragmentation; and they must struggle for urban and national-level social policies that guarantee sectorally balanced urban employment patterns and alternative land uses, all in order to prevent the social and spatial polarization of urban life and the compartmentalization of physical spaces and economic activities into high and low-end activities, that compete with, rather than complement, each other. It is only by undertaking this massive cross-sectoral effort to engage citizens and the state at a variety of levels, that social peace and urban harmony can be achieved.