2009 Online Exclusives

Iran's George Washington: Remembering and Preserving the Legacy of 1953

By Sam Sasan Shoamanesh

We approach the 56-year anniversary of the 1953 coup removing Mohammed Mossadegh as Prime Minister of Iran. Given the challenges that continue to confront the world to this day, it is important to revisit the lessons of this fateful event. An understanding of 1953 seems particularly poignant as the US and the international community grapple with the question of Iran amidst unprecedented levels of internal discord. With seldom seen primary evidence, archived photos and historical correspondence, this essay hopes to shed light on what this event has meant to the Iranian people.

Devising an effective policy towards Iran necessitates an understanding of historical causes of tension between Tehran and Washington. By providing a historical lens through which to view and analyze the Iran quandary for the interested reader and policy maker, the author highlights the following lessons to be derived from one of the most ruinous cases of foreign intervention in Iranian internal affairs.

The 1953 coup has spawned a tragic legacy. It has:

(i) proved to be a blowback in American foreign policy and served as one of the major contributors to the continued souring of US-Iran relations;

(ii) worked to directly impede Iran’s indigenous push towards secular democracy and political development;

(iii) created a culture of ‘mistrustful minds’ within a segment of Iran’s population, who have an embroidered habit of suspiciously looking at the West. Members of this group would later enter politics in the country post the 1979 Revolution. In lieu of handling challenging geopolitical and realpolitik realities with sound sustainable policy, their anti-Western ‘complex’ has obstructed the ability of this latter group to advance the national interests of the country. The preference has been to opt instead for a rigid self-defeating rejectionist posture and policies to the detriment of the Iranian people. The emergence of a new Great Game in the region and the cementing of the Moscow-Tehran-Beijing axis has only served to complicate this dynamic;

(iv) provided a pretext to rogue elements within the ruling elite to rely on a past history of foreign intervention in the country to scapegoat failed domestic policies and silence dissent; conveniently tying any legitimate questioning of the government’s policies by the people to nothing more than external meddling. The recent post election crackdown and the mass “show trials” in the country are cases in point.

Remembering the 1953 Coup at its 56th Anniversary

The year is 1789. George Washington has just been inaugurated as the first President of the United States. He has earned the respect of liberty seeking people of the newly formed confederation, by defeating the British army in the Revolutionary War and presiding over the drafting of the Constitution.

Now imagine a clandestine operation; orchestrated by a foreign intelligence service to undo this turn of events. Imagine what the United States would look like today if this epic hero of America’s founding was abruptly overthrown. Washington's only ‘crime’: devotion to his country and a vision calling for an independent, democratic and prosperous homeland.

The operation would crush the nascent and fragile American democracy, leaving Americans betrayed for years to come. Could one truly measure the full impact and fallout of such an intervention?

While abstract, this tragic “tale” is in actuality the real Iranian experience. August 19, 1953 will mark the 56th anniversary of the CIA-orchestrated coup d’état that deposed Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh and derailed Iran’s burgeoning democracy. Dr. Mossadegh – the man whom Time magazine had called “The Iranian George Washington” – represented for Iranians a symbol of change, a champion of (secular) democracy, and a source of valiant resistance to foreign dominion over Iran’s resources and colonial subjugation.

The 1953 coup – CIA’s first in the Middle East – triggered a series of cause-and-effect outcomes that have not only tarnished Iran-US relations and changed the domestic political landscape of the country; it has made dialogue a perturbing challenge, haunting relations to this very day. To be sure, the coup is the first and one of the most severe blowbacks of American foreign policy in the Middle East.

When former President Jimmy Carter was confronted with a comment alluding to America’s role in the coup, he replied: “that’s ancient history.” His presidency marred by the American hostage crisis, Carter neglected the critical implications of 1953. To the contrary, history matters. The 1979 Revolution, the hostage crisis, and the Iranian government’s suspicions and declarations of US-Western motives (both before and after June 2009's disputed elections) all illustrate how prominent a blow the CIA's intervention has continued to inflict on the Iranian consciousness, and Tehran's ruling elite in particular. Senator Jay Rockefeller (D-WV) captured this reality in a 2006 speech:

It was 53 years ago that the United States and the United Kingdom worked their way to overthrow the Prime Minister of Iran, Mossadegh. When you bring that up in a conversation these days, people say, “Who?” But that was 53 years ago. To understand Iran, you must understand that for Iranians, this event happened last night. It is of the moment. It defines us even for what we did so many years ago. (1)

1.0. Nationalization & Oil Politics

A neutral observer as a guest of this beautiful and hospitable country cannot help but agree with the view of the Iranians. There is no doubt that the Oil Company has been a government within a government and has interfered in the internal affairs of Iran so far that even it has had a hand in changing governments and dynasties.

Le Figaro, French daily Newspaper (Paris, 16 June 1951)

To trace the roots of Tehran’s animosity towards Washington and the West in general, one must turn the pages of history not only to the Cold-War dynamics often cited by academics; but to the cause of oil politics as well.

Oil: A Blessing and a Curse

Apart from its vast gas coffers and other natural resources, Iran has the largest oil reserves in the world after Saudi Arabia and Canada. This important resource has been as much a curse as it has been a blessing for the country. Looking back, one can reasonably state that no one private company has been so instrumental in shaping a country’s recent history than the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC) in its dealings with Iran.

Later known as the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC) in 1935, and eventually British Petroleum, APOC's legacy has lasted for over a century.

Oil was struck in Iran in 1908. APOC was born from an oil concession obtained by a British national from the fifth Qajar King of Iran. The concession was to last for 60 years in territories covering most of Iran. In exchange, the Iranian monarch was promised a personal payment of 20,000 pounds sterling, shares in the company, and 16 percent of future profits. APOC was the first company using oil reserves in the Middle East and the refinery later built in Abadan, Iran, was for some 50 years the largest in the world. Recognizing the importance of Iranian oil to British power, the British government swiftly moved and partially nationalized APOC in 1914, assuming control of some 53 percent of the company’s shares.

With no oil of its own, and aggravated by its abundance of colonies devoid of black gold, Britain had significant interests in ensuring control over the flow of Iranian oil. Britain's interests included not only those of its navy – at the time, the heart of British power – but also the success of its entire economy at large. From the 1920s through the ‘40s, Britain received all of its oil from Iran, and enjoyed a reasonably high standard of living at least in part as a result. Meanwhile, APOC’s Iranian workers, not to mention much of the Iranian population, lived in abject poverty. To counter these deficits with any meaningful social or industrial reform, the Iranian government relied heavily on oil revenues to jumpstart such initiatives. It soon became apparent that with such little control of its country's oil resources, Iran was paralyzed to realize these aims.

What's more, APOC increasingly engaged in unfair practices and failed to honor even the marginal royalties that it had contracted to pay Iran. In 1948, for example, while APOC reported profits of ₤62 million and paid the British government ₤28 million in income taxes, Iran received a meager ₤1.4 million on its oil resources. The company also regularly reneged on obligations and withheld payments when its demands on the Iranian government were not met.

1.1. Emergence of Official Opposition

Unsurprisingly, opposition both within Iran’s ruling elite and masses began to grow against the terms of the oil concession. Based on the historical evidence, a talented first Minister of Court of the Pahlavi Dynasty, Abdol-Hussein Teymourtash, who is credited with playing a defining role in modernizing Iran, was one of the first to spearhead an official challenge to APOC’s practices. Iran’s position at its core was that the country’s wealth was being squandered, and the concession initially accorded to APOC was contracted under duress by a non-constitutional government of the Qajar dynasty.

On behalf of Iran, Teymourtash requested, inter alia, a 25-percent share in the company. If a new concession was to be drawn, he stressed, only a 50-50 split would be acceptable. His “bold” demands placed Teymourtash on a fast collision course with the British government.

He was later removed as a result of British pressure and maneuvering by his internal enemies, first dismissed from his official functions and later arrested, strangely, on charges that he secretly entered into negotiations in favor of the British government and the oil company. Sacrificed to restore British-Persian relations at a time when Britain was threatening to sever ties and position troops in the Persian Gulf, Teymourtash died in solitary confinement (1933) under suspicious circumstances having endured regular torture. With the Teymourtash factor out of the equation, the Iranian parliament negotiated and ratified a new agreement with APOC in May 1933. Amongst its terms, the new agreement renewed the contract for a further 60 years, guaranteeing a minimum annual payment of 750,000 pounds sterling, while exempting the company from import and custom duties.

What followed were 20 more years of unfair practices by the oil company, a sheer disparity between income tax provided to the British government and the royalties Iran received on its own oil, continuing poverty for the Iranian people and unacceptable working conditions for Iranian laborers of the company as reported by, inter alia, the International Labor Organization.

1.2. Mossadegh and the National Front

The emergence of the National Front of Iran, founded by Prime Minister Mossadegh and 19 other like-minded Iranians, gave Iranians renewed hope of achieving a more democratic and economically independent Iran. A long serving politician, Dr. Mossadegh stormed the Iranian political scene in the early 1950s with the romance attributed in the West to charismatic and notable public figures amongst the ranks of George Washington, General Charles de Gaulles, John F. Kennedy, Pierre Trudeau and more recently, President Barrack Obama. A graduate of universities in Tehran, Paris and Switzerland where he obtained his PhD in law, Dr. Mossadegh served the country in different capacities, including as prime minister, ministers of finance and foreign affairs. As a young rising statesman, Dr. Mossadegh had supported the constitutionalists in the Constitutional Revolution of 1905-1911, restricting the absolute powers of the traditional Iranian monarch, notwithstanding ties with the royal court through his mother. As a politician, he called for political and economic independence; the strengthening of civil society, and competent, corruption-free government. He further advocated for an independent judiciary, free elections, freedom of religion and political associations, women’s and worker’s rights, and projects aimed at supporting the country’s large agricultural sector. For all intents and purposes, he was to the majority of Iranians, the figure of a national hero, the new founding father of Iran in the modern age, who carried on his aging shoulders the promise for democracy and true independence – he was to many the “Iranian George Washington."

After taking office in 1951 as Prime Minister, Mossadegh led the National Front’s campaign to nationalize Iran’s oil industry by sponsoring nationalization bills passed by Parliament in March 1951. The Oil Nationalization Act received Imperial assent on 1 May 1951. This act of “hostility” as perceived through the British lens quickly resulted in mayhem. Oil production came to a standstill as British technicians left the country en masse, damaging refineries on departure. Britain moved aggressively and took a series of steps to penalize Iran. An embargo on the purchase of Iranian oil as well as a ban on exporting goods to Iran were soon put in place, as were measures to freeze Iranian sterling assets. Britain mobilized its navy and paratroopers as a show of military might and Iran was placed under increased pressure to abandon its nationalization plans (against this historical background, the current international response to Iran’s nuclear program, justly or not, is a déjà vu in the eyes of the Iranian authorities). The message for Iranians was clear – their interests or rights over their own natural resources mattered little.

1.3. Showcase Before the World: Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (United Kingdom v. Iran)

They are trying “to persuade world opinion that the lamb has devoured the wolf.”

From Prime Minister Mosssadegh’s speech (1951)

To place increased international pressure on Iran, the British government first resorted to legal maneuvering by initiating proceedings before the then newly created International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague, Netherlands. On May 26, 1951, the British government holding the lion’s shares of AIOC submitted an Application requesting the Court to uphold Iran to the 1933 agreement, seeking compensation and damages for adversely impacting the profits of the company.

|

Courtesy of the International Court of Justice. All rights reserved.

Figure 1: Representing Great Britain and Northern Ireland: Sir Lionel Heald, Q.C., M.P., Attorney-General; Professor C. H. M. Waldock, C.M.G., O.B.E., Q.C., Chichele Professor of International Law in the University of Oxford; Mr. H. A. P. Fisher, Member of the English Bar; Mr. D. H. N. Johnson, Assistant Legal Adviser of the Foreign Office, as Counsel; hlr. A. D. M. Ross, Eastern Department, Foreign Office; Mr. A. K. Rothnie, Eastern Department, Foreign Office.

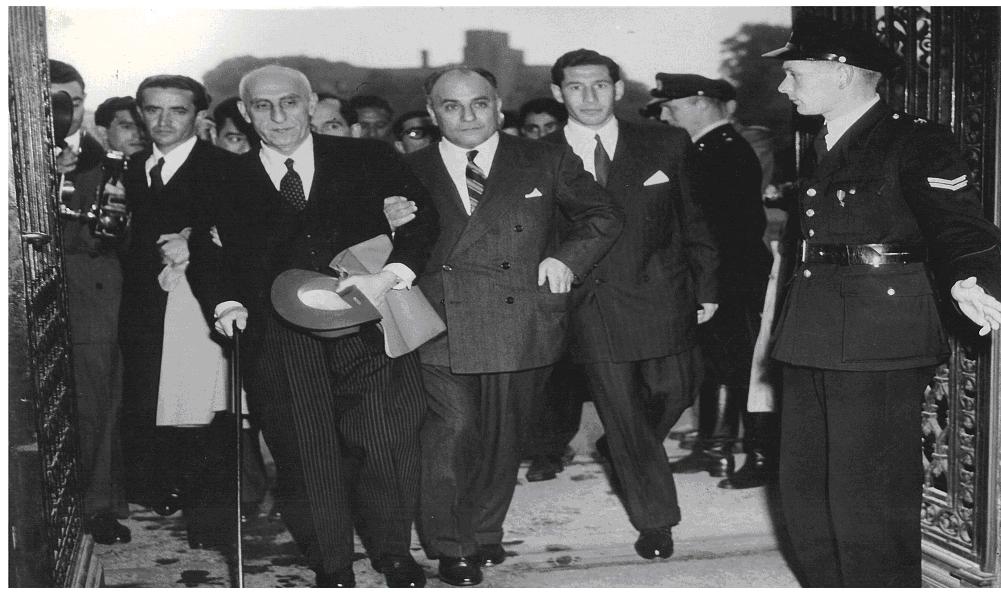

Prime Minster Mossadegh wanted to be involved personally in defending Iran’s position. Notwithstanding his deteriorating health and old age, he led Iran’s legal team to defend the Iranian parliament’s decision.

|

Courtesy of the International Court of Justice. All rights reserved.

|

Courtesy of the International Court of Justice. All rights reserved.

Figures 2 & 3: Mossadegh, being assisted by his son, enters the Peace Palace, seat of the ICJ during the proceedings.

As negotiations between the British and Iranian governments continued to be frustrated, the US was initially brought in as a mediator. In a June 11, 1951 personal letter to President Harry Truman (2), Mossadegh described the reasons why Iran had to nationalize the oil industry. The letter has been reproduced below (3). This important diplomatic communiqué was drafted at a time when Iran’s leadership, not to mention Iranians themselves, looked to the US as a “model” Western power that stood for self-determination and democracy devoid of colonial intervention in their country. In this sprit and the fact that Prime Minister Mossadegh was incisively aware of American concerns over the disruption of the flow of oil, he wrote:

[T]he Iranian people and their Government have always considered the United States of America as their sincere and well wishing friend and are relying upon that friendship.

Concerning the nationalization of the oil industry in Iran, I have to assure you, Mr. President, that the Government and Parliament of Iran, like yourself, desire that the interests of the countries which hitherto have used the Iranian oil should not suffer in the slightest degree. As, however, you have expressed the apprehension of the United States, and it would seem that the matter is not fully clear to you, I ask permission to avail myself of the opportunity to put before you a cursory history of the case and of the measures which have now been adopted.

For many years the Iranian Government has been dissatisfied with the activities of the former Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, but I feel it would be beyond the scope of this letter and would cause you undue trouble if I attempted to set forth in detail the exactions of that Company and to prove with unshakable documentary evidence that the accounts of the Company have not corresponded with the true facts and that, even in their disclosed accounts, the share they have earmarked for the Iranian people, the sole owners of the soil, has been so meager as to rouse the indignation of all fair-minded persons.

The Iranian people have suffered these events for a good many years, with the result that they are now in the clutches of terrible poverty and acute distress, and it has become impossible to continue this tolerance, especially with the situation brought into existence in this country by the Second World War. No doubt you will recall, Mr. President, that during the war Iran collaborated fully and most sincerely with the Allies for the ultimate triumph of right, justice and the world freedom, and that she suffered untold hardships and made many sacrifices. During the war all our development activities came to a stand-still, as all our productive resources were directed day and night to carrying out large-scale plans for the transfer of ammunitions, the supply of foodstuffs and other requirements of the Allied armies. These heavy burdens, borne for several years, disorganized and weakened our finance and economy and brought us up against a series of very grave economic problems, with the result that the laboring classes of this country, who had toiled for the Allies throughout the war were faced with an unbearable rise in prices and wide-spread unemployment…

Had we been given outside help like other countries which suffered from war, we could soon have revived our economy, and, even without that help, could have succeeded in our efforts had we not been hampered by the greed of the Company and by the activities of its agents. The Company, however, always strove, by restricting our income, to put us under heavy financial pressure and by disrupting our organizations, to force us to ask its help and, as a consequence, to submit to whatever it desired to force upon us.

He goes on to state:

Secret agents, on the one hand, paralyzed our reform movements by economic pressure, and, on the other hand, on the contention that the country had enormous sources of wealth and oil, prevented us from enjoying the help which was given to other countries suffering from the effects of war.

I ask you in fairness, Mr. President, whether the tolerant Iranian people, who, whilst suffering from all these hardships and desperate privations, have so far withstood all kinds of strong and revolutionary propaganda without causing any anxiety to the world, are not worthy of praise and appreciation, and whether they had any other alternative but recourse to the nationalization of the oil industry, which will enable them to utilize the natural wealth of their country and will put an end to the unfair activities of the Company.

After providing details of what safeguards were given to the company and the British government, Prime Minister Mossadegh ends his note by giving assurances to President Truman.

The aim of the Iranian Government and the Mixed Committee in adopting the above measures has been the continuation of the flow of oil to the consumer countries – an aim which has been your immediate concern.

You may rest assured, Mr. President, that the Iranian people are desirous of maintaining their friendship with all nations and especially with those, like the British nation, which have had age-long relations with them […].

I avail myself of this opportunity to offer to you, Mr. President, the expression of my highest and most sincere regards, and to wish the continuous progress and prosperity of the great American nation.

(Signed) Dr. MOHAMMAD MOSSADEGH (4)

In July 1951, with British-Iranian tensions continuing to rise, President Truman dispatched Secretary of Commerce Averell Harriman to Tehran to preempt a confrontation. The Truman administration opposed military action against Iran and appears to have sympathized with its position. Truman’s Democrats were seemingly of the view that diplomacy should be employed as a first strategy in dealing with the nationalization question. The following summary of the statement made by General Patrick J. Hurley before a Senate investigation committee convened in June 1951 is telling in this regard:

[T]he danger in Iran is from an imperialistic and colonial policy and not from communism. The Shah and the people of Iran had repeatedly complained to him about the colonial policy. And in this dispute the Oil company, who made enormous profits and gave a very small share to Iran, is to be blamed. It would have been more appropriate and just to sit down and see what can be done instead of threatening the country by paratroops. However, this was not done and like many similar problems it is now too late. (5)

|

Courtesy of the International Court of Justice. All rights reserved.

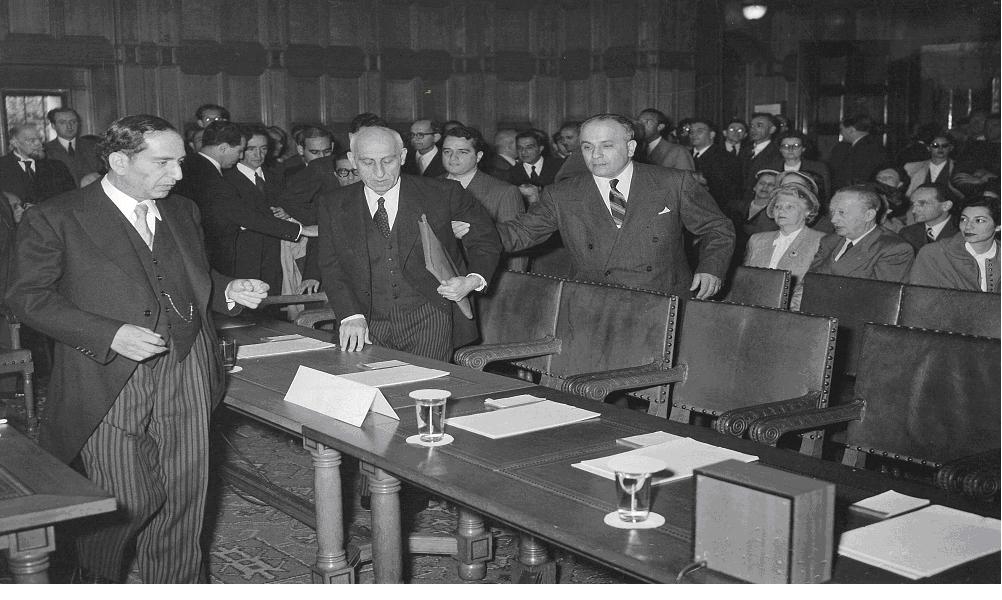

Figure 4: Prime Minister Mossadegh assisted by his son about to be seated in the ICJ.

US-Iran diplomacy had prevailed for the time being and relations remained cordial while the legal battle between the UK and Iran proceeded.

|

Courtesy of the International Court of Justice. All rights reserved.

Figure 5: Representing the Imperial Government of Iran: M. Hussein Navab, Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipstentiary of Iran to the Netherlands, as Agent; Dr. Mossadegh, Prime Minister; assisted by M. Nasrollah Entezam, Ambassador, former Minister; M. Henri Rolin, professor of international law at Brussels University, former president of the Belgian Senate; M. Allah Yar Saleh, former Minister; Dr. S. Ali Shayegan, former Minister, Member of Parliament; Dr. Mosafar Baghai, Member of Parliament; M. Kazem Hassibi, Engineer, Member of Parliament; Dr. Mohamad Hossein Aliabadi, Professor of the Tehran Faculty of Law; and M. Marcel Sluszny of the Brussels Bar.

|

Courtesy of the International Court of Justice. All rights reserved.

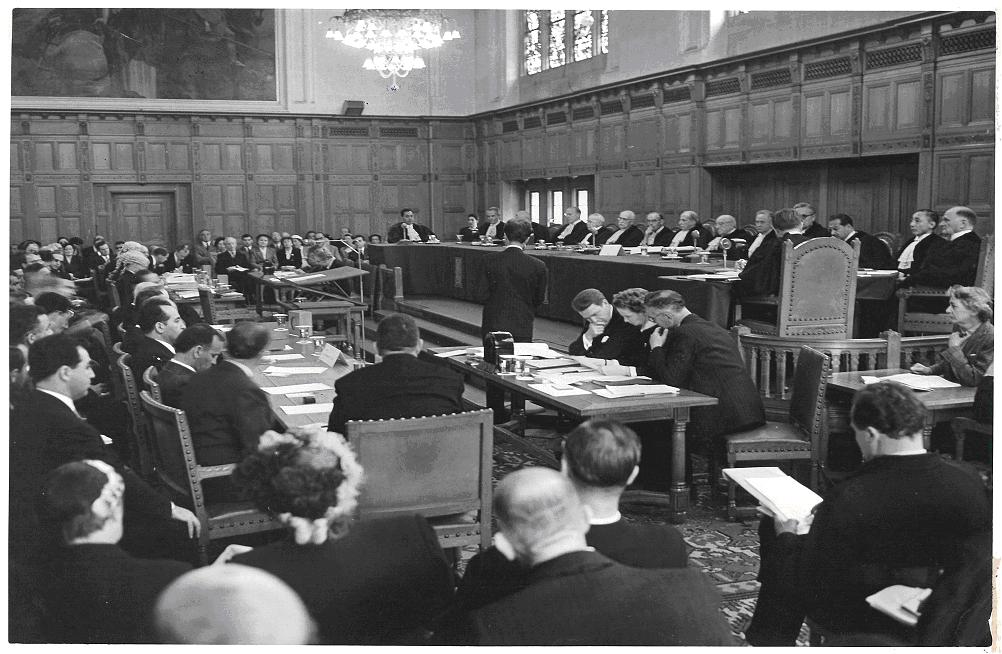

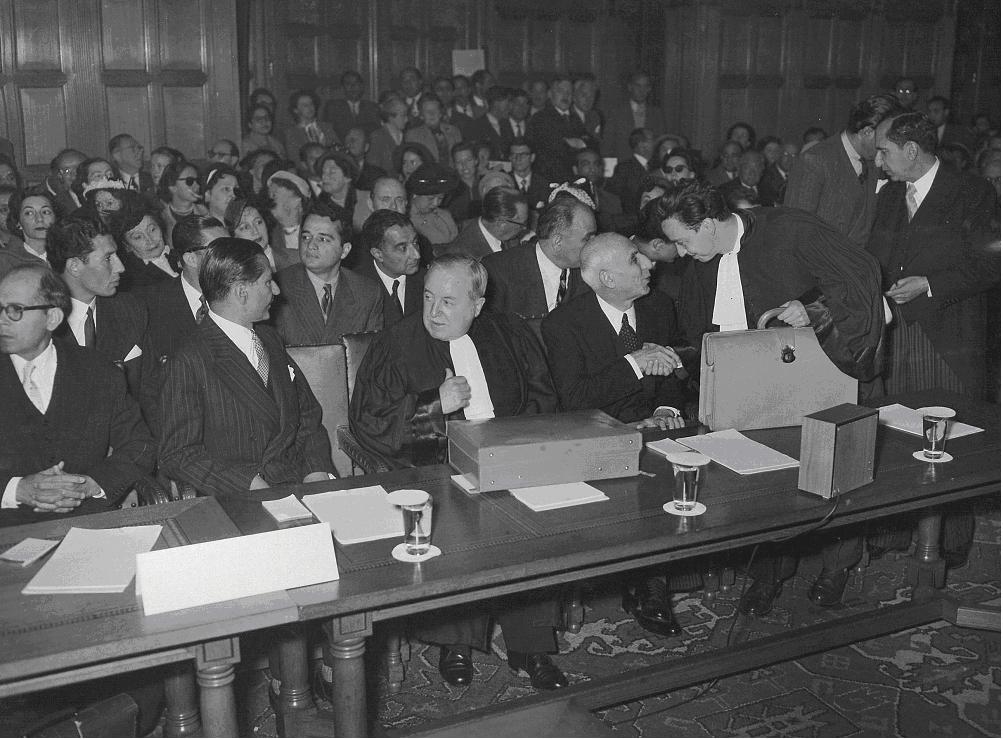

Figure 6: A view of the Court in session; submission being made by the Iranian delegation.

Later, with Iran proceeding with its takeover of the oil company, Britain referred back to the ICJ, this time seeking an injunction (in June 1951) against Iran’s nationalization plans pending a final judgment of the court on the jurisdiction and, potentially, merits of the case. The court granted the British request for an injunction as an interim measure of protection, ordering both parties to take no further action that might prejudice a potential subsequent decision by the court on the case’s merits, aggravate the dispute, or hamper the company’s operations (6). It further ruled that the two countries must establish a board of supervisors to ensure that AIOC’s operations continued unabated (7). The Egyptian and Polish judges of the 14-member panel dissented, opining: “[i]f there is no jurisdiction as to the merits, there can be no jurisdiction to indicate interim measures of protection. Measures of this kind in international law are exceptional in character […], [and] may be easily considered a scarcely tolerable interference in the affairs of a sovereign state” (8). Iran rejected the injunction along the lines of the dissenting judges.

|

Courtesy of the International Court of Justice. All rights reserved.

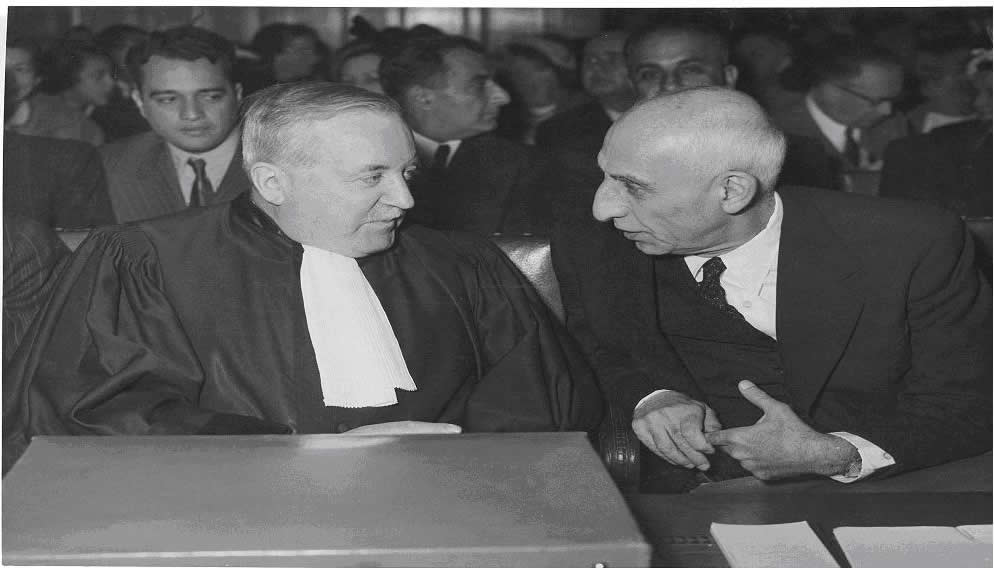

Figure 7: A view of the Iranian and British delegations.

|

Courtesy of the International Court of Justice. All rights reserved.

Figure 8: Professor Rolin conversing with Mossadegh during the proceedings.

|

Courtesy of the International Court of Justice. All rights reserved.

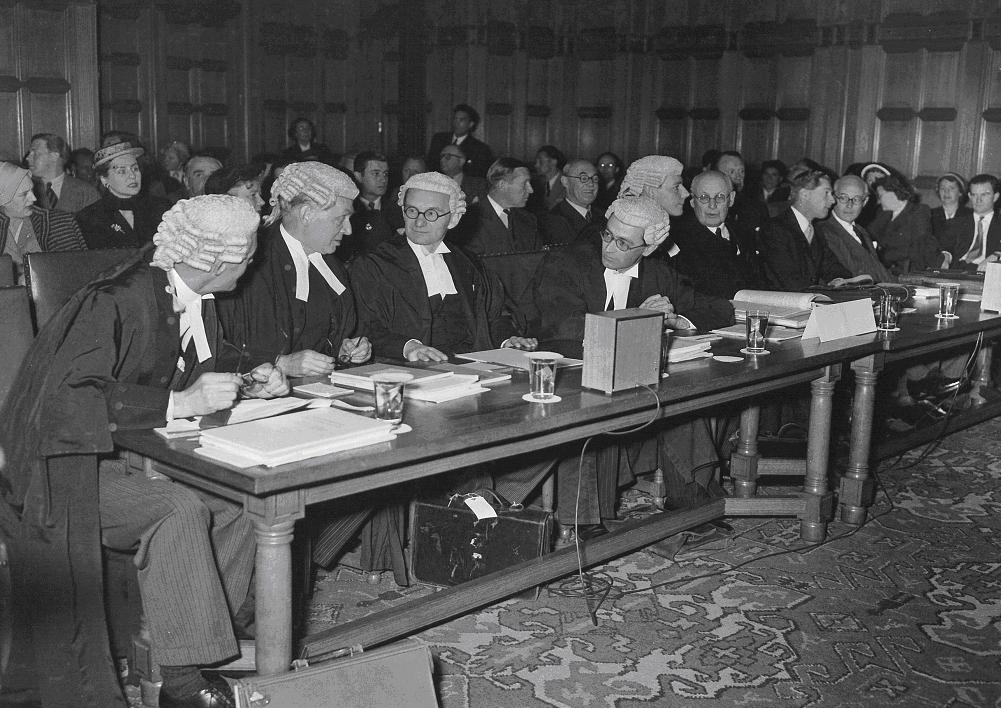

Figure 9: A view of the legal team of Britain and Ireland in caucus.

In Autumn 1951 with the case before the ICJ being litigated, the British government attempted to increase the mounting international pressure on Iran by concurrently bringing the case before the Security Council, complaining of Iran’s refusal to abide the order of the ICJ for provisional measures. It was suggesting, in effect, that Iran’s decision to nationalize was a threat to international peace and security and hence a breach of the UN Charter.

|

Courtesy of the International Court of Justice. All rights reserved.

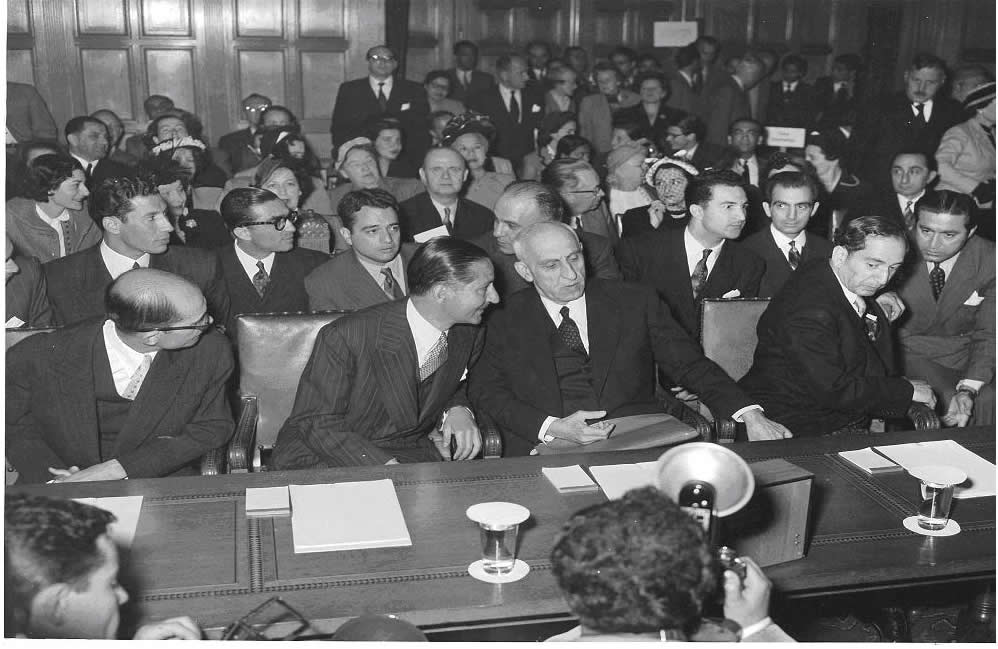

Figure 10: The Iranian delegation to the ICJ.

The Iranians found the Security Council referral most peculiar, questioning if a dispute between a private oil company and Iran – what should have been a purely domestic matter – was a question of maintenance and restoration of peace and security (Chapter VII of the UN Charter). And this at a time when it was British ships which were stationed in the Persian Gulf, making military threats against Iran’s territorial integrity. In the context of the Cold War, the Soviet Union and China capitalized on the dynamics at hand and sided with Iran at the Security Council.

|

Courtesy of the International Court of Justice. All rights reserved.

Figure 11: Prime Minister Mossadegh conversing at the ICJ with M. Nasrollah Entezam, Ambassador, former Minister and the only Iranian to have served as President of the UN General Assembly.

Mossadegh also led the Iranian delegation before the Security Council in New York as he had done in The Hague. He declared the United Nations to be “the ultimate refuge of weak and oppressed nations, the last champion of their rights” (9).In challenging Britain’s draft resolution, he charged that “it requires a deficient sense of humor to suggest that a nation as weak as Iran can endanger world peace…Iran has stationed no gunboats in the Thames” (10). He emphasized that Iran is “not prepared […] to finance other people’s dreams of empire from our resources” (11). The move to engage the Security Council was a diplomatic debacle for the UK, and on October 19, 1951, the council postponed the discussion on the draft resolution until the ICJ had rendered its final judgment.

It is interesting to note that while in the US, Mossadegh made symbolic visits to Independence Square and the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia. There in a public lecture he compared Iranians’ aspiration for independence as manifested in the decision to nationalize the country’s oil industry with Americans’ quest for freedom as seen in their opposition to foreign dominion in 1776 (12).

In response to the British complaint before the ICJ, Iran ultimately filed an objection before the court (on February 4, 1952) challenging the court’s jurisdiction.

Finally on July 22, 1952 by a 9-5 vote, the ICJ declared that the 1933 agreement could not constitute a treaty between the two states as the UK claimed, but merely a concessionary contract between a private company and the government of Iran to which the UK was not a party. The court declared it lacked jurisdiction – as contended by Iran – to rule on the merits of the case (13).

|

Courtesy of the International Court of Justice. All rights reserved.

Figure 12: A view of Iran’s delegation. Mossadegh being greeted.

This judicial ruling, one of the ICJ’s first, would prove critically important in what was to follow. It ended Britain’s hopes of gaining an internationally recognized solution to the nationalization question in favor of its interests. The United Kingdom had just suffered catastrophic diplomatic losses before the World Court as well as the Security Council. And yet its problems remained intact. Iran was advancing with its nationalization plans and now had the international community’s backing. Moreover, Mossadegh’s diplomatic successes before the ICJ and Security Council had won him not only a great deal of respect in the streets of Iran but also sympathy from listeners abroad.

|

Courtesy of the International Court of Justice. All rights reserved.

Figure 13: Mossadegh assisted by his son and members of the Iranian delegation walking in the halls of the Peace Palace, home of the ICJ.

As a clearly visible exhausted Prime Minister Mossadegh walked through the halls of the Peace Palace, having just successfully defended Iran’s position, there was little room for celebrations. Perhaps he intuitively knew Iran’s difficulties were far from over. History was to prove such intuitions well founded.

Apart from growing British discontentment with the turn of events, the embargoes and the drastic reduction in oil output had placed extreme pressure on Iran’s economy, thereby triggering domestic divisions. Furthermore, frustrated by Iranian resilience, Westminister Palace became convinced that Mossadegh posed a direct threat to British interests and had to be removed. As with Teymourtash decades earlier, Mossadegh presented as an obstacle to British interests and ‘had’ to be neutralized. A resort to the British Intelligence Service was made, yet an attempted coup was uncovered and bore no fruit. In retaliation, the Iranian government severed diplomatic ties (November 1, 1952). Anxious about what losing Iranian oil would mean for the British navy and economy, Winston Churchill, by then prime minister, lobbied the Americans to commit the deed.

As the Cold War developed, the UK thusly framed its argument: Iran is strategically positioned, rich in oil, sympathetic to the Tudeh party (the Communist party in Iran against which, in fact, Mossadegh had taken strong measures), and, therefore, on the verge of falling into Soviet hands. A formerly classified report addressed to the US National Security Council in November 1952, speaks volumes to the increasing anxiety Washington felt at the time over the escalating crisis and how British moves were successful in influencing American policy makers. Still whilst Truman was willing to confront militarily a Communist takeover of Iran, even his doctrine of Soviet containment would not permit him to accept a coup or to allow a British invasion of the country. It appears he had hoped as a first strategy to not disturb the oil flow, diplomacy would convince the Iranians to give up or make concessions on their nationalization plans.

The dynamic changed, however, when President Dwight Eisenhower – a man who earnestly contemplated nuking Moscow to prevent the Soviet Union from becoming nuclear (14) – came to power in January 1953 with John Foster Dulles as his secretary of state. The latter, apart from being a public supporter of the Nazi Party in the early 1930s, was against the very notion of nationalization, let alone nationalization of such an important resource. He famously quipped: “[t]he United States of America does not have friends; it has interests.” His younger brother, Allen Dulles, headed the CIA. Both had represented corporate interests and American oil companies in previous professions as lawyers. Soon policy discussions at the National Security Council took a drastic change from the Truman years – now, covert or “special political operations” were on the table.

The new view that emerged in Washington was that Mossadegh’s precedent could not be tolerated lest it trigger a domino effect of nationalization movements worldwide that could threaten American and Western interests. After all, in 1951, the Egyptians abrogated the 1936 Anglo-Egyptian treaty that had granted Britain control over the Suez Canal, thereby prompting another crisis that would sow the toppling of the Egyptian monarchy. President Gamel Abdel Nasser of Egypt would fully nationalize the Suez Canal in 1956, partly inspired by the National Front’s achievements in Iran.

A joint British-American coup was conceived and mobilized. As BBC would admit years later, “[e]ven the BBC was used to spearhead Britain's propaganda campaign” (15) in support of the coup. Opportunists and Generals loyal to the Shah were approached by the CIA (and MI6), so were allies of Mossadegh, including the influential cleric, Seyed Abdol-Ghasem Mostafavi Kashani who had backed the nationalization initiative, in an attempt to encourage internal divisions and rally support for the coup. Such ploys were successful. Given the code name “Operation Ajax”, it took the CIA operating from the Embassy in Tehran – the same embassy which years later became the scene of the American hostage crisis – a few weeks in August of 1953 to organize a coup and overthrow the democratically elected government of Prime Minister Mossadegh (on 19 August 1953). After the coup, control of Iranian oil was transferred to a consortium in which Britain and the US exercised a profitable level of control, the latter for the first time.

American strategic interests in the coup appear to have been twofold. First, the US sought to prevent Iran from falling into the Soviet camp at all costs. This “threat” was more likely a pretext; indeed, at the time of the coup, CIA and State Department Iranokrats neither believed that Mossadegh and other leaders of the National Front were communists nor that Iran was on the verge of collapse into communist hands. This brings serious doubt on the wisdom and real motivations of the coup, putting aside illegality of the act of undermining a sovereign (democratic) government. The second interest was in maintaining stability in the world’s oil markets and concomitant benefits.

|

Courtesy of the International Court of Justice.All rights reserved.

Figure 14: Mossadegh, deep in thought, along with his son at the Peace Palace.

Following the coup, Mossadegh and other prominent party members were arrested on concocted charges of attempting to overthrow the Iranian monarchy – a presage to other “show trials” the Iranian people would witness in years to come, including the most recent theatre unfolding in Tehran courts. Many were executed, including Iran’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Hossein Fatemi, the father of the nationalization plan. Mossadegh was put on trial and sentenced to death. The Shah later commuted his sentence to three years of solitary confinement, followed by permanent house arrest. He died in exile at the age of 84 in his hometown neighboring Tehran.

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Shah of Iran who regained his throne after the coup through the clandestine tactics of a foreign power would never enjoy legitimacy in the eyes of the Iranian people. Iran’s last monarch had become the victim of his own survival. As he would later lament in old age as a deposed king after the 1979 Revolution: “[i]ngratitude is the prerogative of the people.” His reputation was further tarnished as a result of the cruelty and repression of the infamous Sazeman-e Ettela'at va Amniyat-e Keshvar (“SAVAK”), Iran’s intelligence service, created with direct CIA support, training and encouragement.

In his memoir, The Age of Turbulence, Alan Greenspan, former Chairman of the Federal Reserve (1987-2006) writes: “in 1951, excess Texas crude was supplied to the market to contain the impact on oil prices of the aborted oil nationalization by Mohammad Mossadegh of Iranian oil” (16). He continues, “[p]etroleum is so embedded in today’s economic world that an abrupt severance of supply could disrupt our economy and those of other countries” (17). Then he goes on to make a most revealing statement: “[w]hat do governments whose economics and citizens have become heavily dependent on imports of oil do when the flow becomes unreliable? The intense attention of the developed world to Middle Eastern political affairs has always been critically tied to oil security. The reaction to, and reversal of, Mossadegh’s nationalization of Anglo-Iranian Oil in 1951 and the aborted effort of Britain and France to reverse Nasser’s takeover of the key Suez Canal link for oil flows to Europe in 1956 are but two prominent historical examples. And whatever their publicized angst over Saddam Hussein's ‘weapons of mass destruction,’ American and British authorities were also concerned about violence in an area that harbors a resource indispensable for the functioning of the world economy” (18).

Nationalization of Iran’s oil, the first bold move of its kind in the Middle East and the reactions to it, laid the foundation for a tsunami wave of cause and effect outcomes that would storm the socio-political landscape of the country and ultimately, significantly impact Iran’s relations with the US after the 1979 Revolution.

Lessons to be drawn

On June 4, 2009, President Obama made a frank admission in discussing colonialism as one of roots of tension between the West and the Middle East. He stated “the United States played a role in the overthrow of a democratically elected Iranian government […] Rather than remain trapped in the past, I’ve made it clear to Iran’s leaders and people that my country is prepared to move forward. “ It is important to note that many Iranians, rightly or wrongly, blame America’s role in the overthrow of the Mossadegh government as one of the chief sources of their country’s subsequent history of authoritarian rule, with its unfortunate side-effects still being felt today. In sum, in August 1953, the CIA imposed a severe blow to Iran’s indigenous steps towards secular democracy and independence. “Observe good faith and justice toward all nations. Cultivate peace and harmony with all”, words uttered by President George Washington had fallen on deaf years. The damage was done. With the benefit of hindsight, one can reasonably conclude that if not for the coup, Iran would have been a different country today, as would Iran-US relations. This understanding is important for American policy makers. The Iran question should not be analyzed in a vacuum divorced from the sour historical realities weighing down on US-Iran relations.

There are yet further consequences of the legacy of the 1953 coup, which for three decades have been playing out in a most perverse fashion in Iran. Sadly after the 1979 Revolution, when politically convenient the Iranian authorities have incongruously invoked the dreadful memories of the coup amongst other instances of foreign intervention in the country. Such ‘penchant’ for history has equipped elements of the Iranian government to incessantly pin the blame on a foreign enemy – real or imagined – in a desperate search for legitimacy and to detract attention away from failed domestic policies. Worse, this exploitation of history has also served to silence any indigenous legitimate questioning of the status quo in the country. Associating a highly sophisticated mass movement demanding expanded freedoms, real democracy and political reform post the June 2009 elections to foreign plots to change the regime and recent 'show trials' are yet further examples of this tendency to misuse the tragic memory of the past to stifle political dissent. A mere look at the charges cited by the ‘prosecutor’ overseeing the mass post election show trials in Iran is insightful in this regard (“The victory of the Islamic Revolution had threatened the colonial interests of foreign powers in Iran and in the strategic area of the Persian Gulf, resulting in increased enmity toward Iran […]”). The realpolitik observer may inquisitively ask: but did intelligent services of nations that have a stake in who runs Tehran somehow contribute to the post election turbulence? We will know in time, yet it is highly unlikely at any meaningful level, if at all, for reasons beyond the scope of this commentary. What is certain, however, is that rogue elements within the ruling establishment in Tehran have unleashed a violent post election crackdown resulting in grave human rights abuses in breach of the country’s very own constitution. There is no doubt about this fact. There is no justification for violating fundamental human rights and such breaches should never constitute “politics by other means.” In sum, the labelling of the post-election rift in Iran and millions of Iranians struggling for change as nothing more than foreign tampering is a crass perversion of the past, serving only to re-victimize the Iranian people. Sovereignty of the people must finally be recognized and respected.

From a macro level analysis, history of modern Iran from the Constitutional Revolution of 1906 to the present day can be adequately described as a continuous movement towards independence, a freer identity in the face of internal corruption and external influence, social justice and democracy. Not all manifestations of this movement have materialised as expected, while others were outright derailed and denied progress by external interferences. Nevertheless, Iranians are and remain steadfast in their pursuit for a full democratic expression and real autonomy. The most recent unrest in Iran is yet a further example of this forward thrust – no doubt, an inspiration for many in a region dominated mainly by one-party political systems.

This commentary is offered in the hopes that Barack Obama’s presidency and what appears to be a new and nuanced modus operandi in American foreign policy may provide not only unique opportunities for US-Iran rapprochement after 30 years of distrust, but equally for gradual indigenous reform, democracy and respect for human rights in Iran. Lessons of past indiscretions (e.g. 1953) must guide our policies of today. Historically there is close correlation between Iran and its relations with the outside world and how those relations in turn shape the country’s domestic behavior. Recognizing this fact, at this critical juncture any rash policy vis-à-vis Iran will derail the current indigenous struggle for political reform and all that entails for the country’s domestic and foreign policy.

It is the humble view of the author that sound policy and bona fides engagement with Iran at the appropriate time will lay the ground for amicable relations between these two important nations. This will not only be beneficial for the countries’ citizens, but generally for peace and stability of the region and the international community, which may otherwise become increasingly polarized if tensions resume and escalate.

(Please click here for a list of policy suggestions on Iran-US rapprochement).

(Please click here for a timeline of US-Iran relations until the Obama administration).

(Please click here for the constructive modus operandi the US and the international community ought to adopt in response to the post election crackdown in projecting a unified support for human rights in Iran).

*The views expressed in this article have been provided in the authorís personal capacity and do not necessarily reflect the views of the ICC, ICTY, the ICJ or the United Nations specifically or in general.

1. Excerpt from a speech delivered at the 50th Anniversary Gala dinner of the Asia Society (available online).

2. International Court of Justice Archives: Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. Case (United Kingdom v. Iran), “Part III, Other Documents Submitted to the Court” (available online, 685 ff).

3. Ibid. 685 ff.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid. 681.

6. Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. Case (United Kingdom v. Iran), Request for the Indication of Interim Measures of Protection, 5 July 1951, available online (available online).

7. Ibid.

8. Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. Case (United Kingdom v. Iran), Request for the Indication of Interim Measures of Protection, 5 July 1951, “Dissenting Opinions of Judges Winiarski and Badawi Pasha” (available online, 97).

9. Kamrouz Pirouz, “Iran’s Oil Nationalization: Mussaddiq at the United Nations and His Negotiations with George McGhee” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, Vo. XXI Nos. 1 & 2 (2001) , 111.

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid., 112.

12. Ibid., 114.

13. Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. Case (United Kingdom v. Iran), Preliminary Objection, Judgment, 22 July 1952 (available online). This was in fact Iran’s original contention. The country had only conceded to ICJ jurisdiction in cases involving treaties agreed upon after 1932.

14. See Tim Weiner, Legacy of Ashes: the History of CIA, 1st Ed. (New York: Doubleday, 2007), at 75.

15. BBC Radio (available online).

16. Alan Greenspan, Age of Turbulence: Adventures in a New World (New York: Penguin Press, 2007), 444.

17. Ibid., 462.

18. Ibid., 463.