INTRODUCTION

This case study will focus on the reconstruction of Beirut Central District (BCD), carried on by Solidere real estate Company starting from 1991. After the devastating civil war of 1975-1990, the downtown center was heavily damaged and decisions had to be taken in order to rebuild Beirut's urban fabric and sense of national identity.(fig.1: Wadi abu Jamil)

During the war the so called Green Line divided eastern Christian Beirut from western Muslim Beirut, creating a fracture that is difficult to mend. It is clear that the question of identity is an important social phenomenon to take into consideration in the process of reconstruction. Then where to reconstruct, what to preserve, and in what way become very important questions.

From Martyrs' Square to the Damascus road, the Demarcating Line established itself as the 'neutral zone' between the combating sectors in and was the only space bisecting and combining the divided city at the same time. Above all the very heavily damaged center provided a space, some 500 meters wide, which for more than fifteen years remained an emptied-out site marking the graveyard of national dialogue and reconciliation. (fig.2: Building on the Green Line)

The BCD, that used to be the common space for all Lebanese before the war, became a buffer space between them during the war. And since it was not egemonized by any religious subgroup prior to the eruption of the war, it was naturally destined to become their battlefield. The disappearance of the Central District from the daily life of the citizens of Beirut left the city without a center for some twenty years and what was previously a monocentric city transformed its configuration into the currently polycentric one.

CONTEXT

Lebanon is a small country located on the Eastern Shore of the Mediterranean Sea and is surrounded by Syria and Israel. Beirut, which is the capital, is situated as all the major cities on the narrow coastal strip leftover by the mountain ranges. According to Lonely Planet, the international travel organization, "Lebanon packs a lot into its modest borders: ancient cities, Roman ruins, luxurious ski resorts, bucolic charm and Islamic architecture are just the start. Culturally, too, Lebanon is crammed full of complexity, with the kind of full-on religious and social diversity that has monoculturalists in other countries claiming it can only lead to social breakdown - sadly, in this instance, Lebanon did not prove them wrong."

Beiruts urban fabric evolved throughout its rich history and presents nowadays a layering of various cultures. As a matter of fact, due to its strategic location for maritime trades the city of Beirut functioned as a major port since Phoenician age in 550 BC. Beirut was however a small city when adopting the imported grid model of the Greek (hellenistic period), 64 BC. After, between 551 and 560 AD the Byzantine city was shattered by a series of earthquakes, its importance gained during Roman times (395 BC) declined. Later, in the 7th century, under Umayyads Islamic Dynasty, the city of Beirut was fortified and it became the military port of Damascus. During the crusades still the city changed its rulers various times. Then the Mamluk took over from 1291 to 1516 AD before the Ottoman came and made it just a small city in their big empire.

The railroad connection to Damascus in the 19th century revealed the importance of Beirut. At that time, around 1870, the city had only 100.000 inhabitants. In the beginning of 20th century the city developed economically and demographically, following the development example of European capitals such as Vienna and Paris. During the French mandate, starting in 1920, urban renovation and concern for a Western public space became more and more important. Lebanon gained its independence in 1943, and in the following years the newly established republic succeeded in elevating Beirut to the status of modern financial center for the Middle East. The country disintegrated into civil war in 1975, and after fifteen year of fighting, Lebanon was left in a ruinous state. The reconstruction process in Beirut started in 1991 and in particular the Central District project is seen as a chance to reestablish its cultural and economic role catching up with the competing Middle Eastern countries.

THE PROJECT

Planning context In 1941, Lebanon thinks its reconstruction when Mr. Ecochard - at that time Directeur of Urbanism in Damascus, was designated to draw a plan of the new Beirut applying " the same methods used in Syria ." Contrary to Danger's plan (1930) - that is of "urbanism of continuity", Ecochard writes in 1943 a program fixing extension lines, placement of major axes (careless of the urban fabric), thinking about the new city. He is a "progressist" and his plan is of military importance because it is thought to facilitate the liaison with other port towns - Tripoli, Saida. "Ecochard plan did not succeed immediately. In 1964, Ecochard produced his second plan - the plan directeur de Beyrouth et de ses banlieues, including "proposals going well beyond the city proper," although many of these parts of the plan were neglected". (fig. 3)

In 1977, when after two years of fighting the war seemed to be over, the Council commissioned the first reconstruction plan for Development and Reconstruction (CDR). The idea was to rebuilt the downtown center along the lines of the traditional urban fabric, maintaining the specific image of the Mediterranean and 'oriental' city while improving the infrastructures. Unfortunately the war was not over yet, and the plan was never implemented. (fig.4: APUR plan)

In 1983 a private engineering firm, OGER Liban - owned by Rafiq Hariri, billionaire, commissioned a master plan for the reconstruction to the consultancy group Dar al-Handasah. At the same time demolitions, without any control, started in central areas that were called for rehabilitation in the 1977 plan. As a result some of the most significative parts of the urban fabric, such as the traditional souks, were erased. (fig.: 5 / 6 / 7, plans before, during and after).

In 1993, approximately 80 percent of the structures had been damaged beyond repair, whereas only one third had been reduced to such circumstances as a result of damage inflicted during the war itself . (fig. 8: bulldozed center)

In 1990 at the end of the war, given the destruction of the city center and the fragmentation of property rights, a proposal was made to have a single private real estate firm expropriate all the land in the city center and control the rebuilding process. The Law 117 of 7 December 1991 gave the municipal administration the authority to create Solidere, providing the legal framework for the constitution of the company. Solidere's was entrusted with the implementation of the urban plan and the promotion, marketing and sale of properties to individual or corporate developers. This entailed the total and uncontrolled privatization of the reconstruction and conservation operations.

RECONSTRUCTION AND CONSERVATION POLICIES

Conservation approach in Solidere's vision

The main goal of the project is to promote the BCD as the new heart of the city reestablishing, in the words of the Angus Gavin , "its regional role as the former financial, trading, educational, cultural and tourism focus of the Middle East".

The company asserts that the downtown's archeological and architectural patrimony will form an essential element in the competition between the rebuilt center of Beirut and other regional centers - Dubai offers a similar technical infrastructure but lacks Beirut's historical richness, hence that kind of flavor that Solidere can claim to.

Looking at the company's publications, the authors make use of the language of memory and affect to characterize what they promise will be the flavor of the new central district. They claim that preserving "the rich architectural legacy of Beirut and the city center is an important tenet of the Master Plan, which features in this respect the creation of a conservation area in the traditional city center." (fig. 9: Info board)

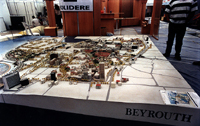

Solidere's Program Interventions (Fig. 10: the model)

Mr Hariri created Solidere - a colony "of the public by private interests". Solidere means the Lebanese Company for the Development and Reconstruction of Beirut Central District. It is an association of two types of shareholders (shares issued to property owner - $1.17 billion and shares issued to investors - $650 billion) of which the common stock totals $1.82 billion.

Solidere wants "Beirut reborn" and that the "past informs the future" in order to render the value of the place in an urban design caring about the neighborhood structure. The plan wants to reveal the national identity and to enhance the city memory. There is, according to Solidere, a special emphasis to the reconstruction of heritage building. Solidere demonstrates the evolution - for the better, in the urban planning with the creation of the highway and the "Normandy" landfill - a modern 61-hectare extension to the city. Solidere planned a mix of uses "as it is traditionally" in Lebanon. Solidere is also claiming its concern for civic value, small scale and a surviving fabric. However, its design purpose is to combine the eastern and the western influences because as it is explained in the web site, Solidere wants to be an "active, attractive, and successful place." Solidere refers to many other projects like the water front in Monte Carlo. Some landmarks that will reveal by contrast to the old urban fabric the orientation and the identity-scale will tell us about the modern city of Beirut.

"The reconstruction and development of the war-torn Beirut Central District will involve a surface area of approximately 1.8 million square meters." 4.69 million square meters will be built up. Within the area of Beirut central district, 265 ancient structures are retained. These structures have three different kinds of historical value: those "in sufficiently sound condition to give them future economic value; the other category includes housing (legal tenants); then the 26 buildings that are governmental, public or religious. Townscape structures like fountains, public stairs are also considered. Most of the 265 buildings are concentrated in the historic center, "the relatively extensive and intact district Nijmeh square area" of variety of periods and style.

The preservation policy included various and deep analysis of the ancient buildings such as the analysis of stones - their provenance and their color. According to Solidere, "since the approval of the master plan and the elaboration of a project phasing plan, a number of studies have been undertaken to expedite and underpin the process of reconstruction". "Restoration briefs have been prepared for all recuparable buildings in the B.C.D." The information, given through the web, is still vague and not much informative of the preservation process.

AUTHORS' CONCLUSION

"The topic of cultural heritage and local tradition in the reconstruction process of Beirut Central District has become indeed a hot one, full of ideological traps and political intrigue. Many voices deplore that a combination of factors has destroyed the heritage and memory of the old center to generate a new space for Solidere's vision of Beirut. In Assem Salam's words "To pretend to protect this memory by preserving a few monuments while obliterating the context onto which they were inscribed can only diminish their real nature"

I believe it is worth looking at the way in which Solidere project attempts to solve the national identity crisis, identifying the Central District reconstruction project with the symbol capable to represent all Lebanese. (fig. 11: Lebanon flag)

To promote this vision of an ideal Beirut as 'layered city of memory' Solidere has re-constructed an image of the city through a suitably tailored national history. As Saree Makdisi pointed out analyzing the company slogan "Beirut - An Ancient city for the Future in which past and future become all but indistinguishable, the one replication of the other, only it is not clear which is the original or whether there was an original to begin with." For instance the recent archeological surveys exposed different layers of Beirut history and now are challenging the primacy of the surface, where the modern city is laying, eventually replacing one ground with several others. (fig. 12: Baths)

Unfortunately the so-called 'contextually sensible' design approach promoted by Solidere tends to refer literally to idealized visions of colonial Lebanon inherited from the Ottoman Empire or France, and does not involves dynamic exchanges between the local tradition and modernity. It seems clear that the simulacra effect of the reconstruction project is to be achieved specifically and solely in visual terms of appearance and façade. The redefinition of historical associations is limited to an iconic pastiche that would be integrated into the project at a level of marketing and aesthetics of the surface. (fig. 13: empty façade)

The threat to heritage, subsequent to the local and parochial concerns for nostalgia, is "the vulgarization of traditional forms of cultural expression and the commodification into kitsch and sleazy consumerism, so rampant is post-war Lebanon" . Kitsch feeds on collective amnesia and the pervasive desire for popular distractions, offering effortless and easy access to the distractions of global entertainment. As designers we cannot ignore the issue of how to commemorate the ugly events of the war and turning them into redemptive and didactic experiences."

Bianca Maria Nardella

"One must also discern in the motto a conceptual model that perceives the city in two ways: as an object that ought to be remembered and thus protected, or as an object that must be historicized and thus transformed in an endless temporal continuum." Fares El Dahdah, On Solidere's Motto, "Beirut, ancient city of the future", Projecting Beirut, 1998.

Although very "politically incorrect", the Solidere project has been well implemented and marketed with claims to create a modern city that addresses also the Lebanese society aspirations: the recovery of their identity. However, Solidere is to some extent making use of the past, and the nostalgic impulse that war generates toward it, as a marketing tool to rebuild a district that is projected to be economically valuable. Thinking about urbanism or analyzing briefly the architecture, one can question the real concern for a past that has been forever lost. In inventing the market center of the future, Solidere destroyed a identity and constructed a fiction of the past.

Referring to the process which Solidere has begun, Makdisi notes the extensive and unnecessary demolitions (fig. 14: Solidere's clean up) that have been carried out in Beirut Central District since 1983, well before the end of the civil war (1990). As a sad example, the old souq that has been destroyed and replaced by another one, a souq. In appropriating merely the name to qualify a new typology, Solidere does not seem to care much about what is really ancient and what is not.

The old fabric of the Beirut Central District being devastated at 80% for no reasons other than to make it more lucrative, it is therefore difficult to understand how identity can be restored. As Erikson says, "when the landscape goes, it destroys the past for those who are left: people have no sense of belonging anywhere." And Samir Khalaf continues, "they lose the sense of control over their lives, their freedom and independence, their mooring to place and locality and, more damaging, a sense of who they are." In a situation of conflict, any cultural or aesthetic dimension is the least of people's concerns - who does not think to react to injuries, and who will worry if others take advantage of it?

From medieval time, Beirut has encountered many changes. In architecture, the traditional typology of the house with a common distribution space has been abandoned since the French Mandate. In the early 60's, Lebanon entered the golden age of modern architecture - meaning functionalism and avant-garde, and wanted to "develop a modern society and a financial and economic center to the scale of the whole region." Later, utopian planners proposed to "rid the Lebanese society once and for all of the detritus of the old form." Solidere does not seem to position itself as a true modernist and refers to a past that effectively deserves protection (Fig. 15 / 16: before and after restoration) but that does not reflect anymore the pre-war Lebanese identity which encountered many earlier evolutions.

Furthermore, the district appears like a city within the city, pushing the demarcation line to its limits, stretching the boundary by implementing a large belt of road, addressing another population - one that did not lose its land and its identity. The project has been built for global people. Solidere 's project does not involve any dynamic exchange between the global and the local because Solidere has a selective memory. Solidere destroyed everything but that was not economically worthy, even the Martyr Place to free the view of the sea in order to build high-income housings (Fig. 17 /18. The Martyr's Place before, after). Moreover, if Solidere funded the rescue excavation of late discovered archeological sites, it is because Solidere "realized that if it did not want its massive infrastructure to be delayed, it would have to pay all the rescue operations in these areas to free them from archeological constraints." Solidere's architecture is an invention of the past, is clean, hygienic and dull denying the real Lebanese society that is struggling outside the new BCD's belt.

Yasmine Abbas

IL N'EST PAS INSENSE DE DIRE QUE L'EXTERMINATION DES HOMMES COMMENCE PAR L'EXTERMINATION DES GERMES (…). LORSQUE TOUT SERA NETTOYE, EXPURGE, LORSQUE L'ON AURA MIS FIN A TOUTE CONTAMINATION SOCIALE ET BACILLAIRE, ALORS IL NE RESTERA QUE LE VIRUS DE LA TRISTESSE, DANS UN UNIVERS D'UNE PROPRETE ET D'UNE SOPHISTICATION MORTELLES."

JEAN BAUDRILLARD, L'ENFANT BALLE, REVUE TRAVERSE, #32, SEPTEMBRE 1984

Fig. 0 Beirut Central District in 1967, URBAMA, BEYROUTH, REGARDS CROISES, 1997

Fig. 1 Wadi Abu Jamil, 1996, Aknowledgment to Michelle Woodward

Fig. 2 Buildings on the green line, Thanks Michelle

Fig. 3 Ecochard plan, "Proposal for the development of the city center," 1963; Projecting Beirut p114, 1998

Fig. 4 APUR plan, Projecting Beirut p130, 1998

Fig. 5 Plan "La ville oubliee," URBAMA, BEYROUTH, REGARDS CROISES, 1997 Fig. 6 Plan "La ville purifiee," URBAMA, BEYROUTH, REGARDS CROISES, 1997 Fig. 7 Plan "La ville ordonnee," URBAMA, BEYROUTH, REGARDS CROISES, 1997

Fig. 8 Bulldozed center, 1996, Aknowledgment to Michelle Woodward

Fig. 9 Info board, 1996, Aknowledgment to Michelle Woodward

Fig. 10 The model, 1996, Aknowledgment to Michelle Woodward

Fig. 11 Lebanon Flag, 1996, Aknowledgment to Michelle Woodward

Fig. 12 Roman baths, 1996, Aknowledgment to Michelle Woodward

Fig. 13 Empty façade, 1996, Aknowledgment to Michelle Woodward

Fig. 14 Drawing, Yaz

Fig. 15 Before restoration, 1996, Aknowledgment to Michelle Woodward

Fig. 16 After restoration, 1996, Aknowledgment to Michelle Woodward

Fig. 17 Martyrs place before, 1996 Aknowledgment to Michelle Woodward

Fig. 18 Martyrs place after, 1996. Aknowledgment to Michelle Woodward

fig. 13: empty façade

Beirut, Lebanon

Conservation and reconstruction in the Beirut Central District.

fig. 3: Ecochard plan

fig.2: Building on the Green Line

fig.4: APUR plan

fig.: 5 / 6 / 7, plans before, during and after

fig. 9: Info board

fig.

10: the model

fig.

10: the model

fig. 12: Baths

fig. 11: Lebanon flag

Fig. 15 / 16: before and after restoration

Fig. 17 /18. The Martyr's Place before, after