|

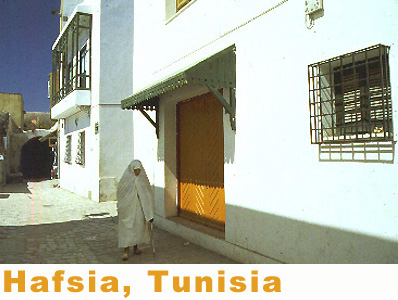

Hafsia Quarter, Medina of

Tunis, Tunisia

Anna Bardos

INTRODUCTION

The Hafsia quarter project is an attempt

to rehabilitate a run-down and largely derelict area in the medina

(old town) of Tunis. The project's goals include providing housing

for the poor, greatly raising the standard of living of the inhabitants,

and recapturing the diversity and life of an urban center. By

maintaining the traditional urban fabric of the medina, this

project recreates the lost physical continuity of the area, thus

enabling social and cultural continuity. It promotes the conservation

and progression of tradition through new buildings rather than

the adaptation of old structures to an altered cultural setting.

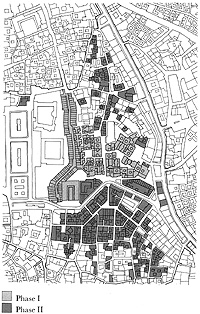

The project spans many years; Phase I was

in effect from 1973-77 and Phase II from 1982-86, with work continuing

until now. Hafsia Phase I won an Aga Khan Award for Architecture

in 1983, as did Hafsia Phase II in 1995.

CONTEXT

Physical

The Hafsia quarter covers about

13.5 hectares in the lower medina of Tunis. It is bounded to

the east by a boulevard built on the former line of the medieval

wall, and to the west by the Rue Archour and Rue Ettoumi. It

is divided into three sub-neighborhoods: Sidi Baian in the north,

Sidi Younes in the south, and a central triangular area containing

developments from the 1930s and 1960s, and the Hafsia I project

area. The site is roughly flat, with a gentle slope of 1 in 100,

ranging from 7 meters above sea level at Rue Archour, and 4.5

meters above sea level in the east. The soil is a mixture of

clay and limestone and the water table is 1 to 1.5 meters below

the ground.

The first phase in the rehabilitation of

Hafsia covered approximately 3 hectares of a larger, mainly demolished,

area in the center and east of the medina and included almost

half of what was then an area of vacant land. The second phase

addressed the surrounding 10 hectares, 22% of which had buildings

in good condition, 38% had structures to be rehabilitated, 12%

had structures to be demolished, and 28% was open land.

Historical

The Hafsia, or Hara, had

been the Jewish quarter of Tunis since the 10th century. As wealthy

families began moving to the newer European areas after 1860,

the Hafsia was left to be one of the poorest areas of the medina.

In 1928 the French authorities declared

the Hafsia quarter a health hazard, and many of the buildings

were demolished between 1933 and 1939. Their plan for rebuilding

the area used a grid design and was comprised of large housing

blocks typical of European cities rather than the traditional

urban fabric of the medina. However, World War II interrupted

this work and bombing resulted in further destruction of the

area.

In 1954 the Hafsia was declared a zone

for 'renewal' by public intervention, thereby prohibiting private

maintenance and so further degrading the area in the meantime.

The area grew in importance in the 1950s because of its proximity

to the developing modern quarters of Tunis. After Tunisia's independence

from France in 1956, the Municipality of Tunis had plans to upgrade

the medina with grandiose projects, and in 1960 the final wave

of slum clearance in the Hafsia took place. Two large-scale primary

schools, a clothing market, a children's club, and a social services

center were built all on an orthogonal axis, again regardless

of the traditional street networks. In 1967 the demolition of

the Sidi El Bechir quarter of the medina almost resulted in a

popular uprising. The grandiose projects were abandoned and the

Association de Sauvegarde de la Médina (ASM Association

for Safeguarding the Medina) was established to study and rehabilitate

the urban fabric of the old city while improving the living conditions

of its inhabitants.

In 1973 the Ministry for Public Works proposed

that a residential and urban rehabilitation plan for the Hafsia

be organized. This became the first phase of the area's rehabilitation,

commissioned by the ASM with help from UNESCO, acting for the

Municipality of Tunis. The project was completed in 1977 and

during 1981-82 a new proposal was conceived by a different ASM

team under the auspices of the Third Urban Project created by

the Ministry for Housing. Again this was in close coordination

with the Municipality of Tunis, this time through the ARRU (Agence

de Réhabilitation et Rénovation Urbaine - Agency

for Rehabilitation and Urban Renewal).

Social, Economic

Throughout most of its history

the Hafsia was inhabited by a mixed population, including foreign

Arabs, Italians, Maltese, and Greeks as well as Jews. As the

affluent Jews left the rundown and overpopulated Hara

only the poorest remained and migrants from rural areas moved

in, attracted by rooms for rent and the proximity to employment.

Houses were divided into one-room dwellings. After independence

population densities rose, making the Hafsia a socially undesirable

living area before the reconstruction. Large proportions of the

land were owned by the Municipality as a result of expropriations

in the 1930s for renewal projects that never materialized.

After the Hafsia I project, the Sidi Younes

and Sidi Baian neighborhoods were still impoverished, with 56%

and 47% of the labor force unemployed, underemployed, or in menial

occupations, and household incomes were well below the SMIG minimum

wage level. Only 21% of the households in Sidi Younes and 10%

in Sidi Baian were homeowners, and 9% and 14% of the inhabitants

were squatters.

Architectural

The reconstruction of the Hafsia

quarter was the first large-scale renovation project of its kind

to be undertaken in an Islamic country. Courtyard houses, narrow

winding alleys and cul-de-sacs traditionally characterize the

Hafsia, although the architecture is not of the aesthetic and

historic value of other parts of the medina. The 1930s additions

of 5-story apartment blocks and the large-scale buildings from

the 1960s break this continuity of dense urban fabric. The Suq-el-Hout,

a former pedestrian route running north to south, had been broken

by a road from the modern quarters of Tunis, attracting modern

high-rise apartment blocks west of the suq. The area east and

south of the suq was largely derelict. Three to four story European-style

tenement buildings from the late 19th and early 20th century

line the east edge of the Hafsia, built on land cleared when

the city wall was demolished in 1893.

THE PROJECT

Significance

In phase one the Suq-el-Hout, a

covered market street of around 100 shops, was reconstructed

and 22 new shops were created on an adjacent pedestrian street,

with offices for professionals above. Ninety-five housing units

were also built.

The significance of this project is that

it was developed using extensive research into the residents'

needs. The ASM defined the requirements of the quarter from their

findings, despite opposition from politicians and some local

and foreign architects and planners, who would have preferred

high-rise housing to be built. However, their intention of providing

housing for low-income families of the area was sabotaged by

the politicians' insistence that the poorest applicants be removed

from the operation in order to attach prestige to the project.

The ASM carried out a detailed survey from

1972 to 1975 on income levels and social backgrounds of future

inhabitants in order to determine their requirements in the layout

of the houses and to compile a commercial report on the shops

needed outside the suq. Nine hundred applications were examined,

which showed their preferences included a quiet residential area

separated from the noisy commercial district and thoroughfares,

independent housing units with private entrances, and courtyard

housing with internal circulation protected from winter weather

with the reception area and living room near the entrance and

the kitchen and more private areas near the back. The differing

requirements of applicants were met by several different house

designs each defined by the floor area as well as the applicants

income and preferences. A survey determined that the shops outside

the suq were to include a restaurant, a café, a laundry,

a barbershop, a shoe-repair shop, and a photographer's studio.

The offices above were to include lawyers, dentists and other

professionals.

The renovated areas of Hafsia I were surrounded

to the north and south by still rundown or derelict areas, which

caused an acceleration of decline in adjacent unrenovated areas

and a lack of continuity. These problems were addressed in the

Hafsia II project. As well as building new housing and commercial

and office spaces, the project included the installation and

improvement of utilities, provision of facilities, maintenance

and repair of infrastructure and streets, provision of car parking,

reorganization of space for economic activity, restoration and

attribution of new functions to historic monuments, and provision

of public or semi-public spaces.

As in the Hafsia I project, surveys were

used to determine user requirements. The foremost objective was

to avoid pushing out the original inhabitants of the area, so

the project tried to ensure an urban homogeneity of the neighborhood.

The project has shown itself to be of great social significance

by creating continuity between the older fabric of the city and

the newer areas, reinstating traditional housing forms, and encouraging

the original inhabitants to remain in the area.

"Hafsia doesn't merely stabilise

the old but transforms the existing texture into a contemporary

condition. People who are interested in restoration are seen

to be standing in the way of progress the Hafsia model is an attempt

to be progressive while holding on to the existing fabric."1

Organization of the Area

The new Suq-el-Hout serves as a

covered walkway, connecting two existing suqs, Sidi Mahrez to

the north and El Grana in Sidi Younes. The road that had previously

severed the existing suq was rebuilt along a zigzag route, with

parking lots for the inhabitants at either end, near the Bab

Carthagena to the east and beside the existing market. Other

pedestrian routes have been extended or introduced throughout

the scheme. The covered suq serves another function, that of

sheltering the new residential area from the 1960s development

to the west.

The Hafsia II project maintains this separation

between pedestrian and vehicular traffic and aims to re-establish

the link between the two poles of rehabilitated buildings, with

an axis crossing through the two projects of new Hafsia housing.

This phase utilized the economic potential well by encouraging

more prosperous inhabitants to rehabilitate their own housing

and by selling off vacant sites to provide loans for the needy.

The project realized that diversifying

the activities present in Hafsia would revitalize the area and

noticed that there was a real need for social and cultural facilities.

To this end they introduced a day care center and kindergarten,

public baths, a health center, three hotels, a group of offices

and a commercial space including a clothing warehouse.

PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION

Spaces and Uses

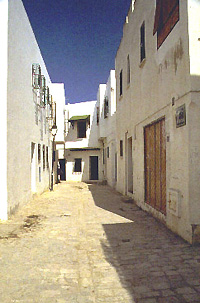

In phase I eleven house types were

defined, ranging from 60 to 163 square meters, including courtyard

houses on one level, courtyard houses on two levels, row houses

with individual enclosed gardens, and row houses built adjacent

to the suq. To capture something of the spatial variety of traditional

North African cities the houses were assembled in different configurations,

clustered around stone-paved common areas and pedestrian streets,

and a few houses were designed to span over the streets. Certain

traditional architectural elements were used, such as white walls

contrasting with colored openings and a small window set just

above the exterior doorway. The maximum height of the houses

was three stories.

In the Hafsia II project, several new apartment

buildings were constructed as a continuation of the European-built

structures on the site of the old wall around the medina. New

patio houses were also built, most of which could be divided

into two dwellings, one opening onto the patio, and one on the

upper level, looking out to the street. Some of the streets are

restricted to pedestrian access. The network of streets integrates

the old and new areas while respecting the traditional city block

sizes and irregularities. The old plot lines were adhered to

for the new infill housing, so each house would be different.

Five plan types were developed to suit small plots and fulfill the requirements of those with low incomes, these were then adapted

to their position in the neighborhood. Housing on the main roads

was restricted to a height of three stories, within the blocks

the maximum height was two stories.

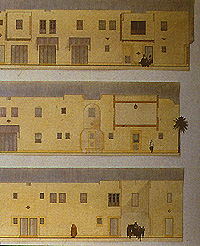

As much of the old quarter as possible

was incorporated into the new scheme and old buildings of suitable

condition or architectural value were renovated. Traditional

vocabulary and typologies were used for the new buildings - facades

are white, with projecting or recessed blocks and deep openings,

and arched entrances and arcades are included where appropriate.

Other traditional elements such as woodwork cantilevers, angle

furnishings, and ceramic framing were simplified to suit new

construction methods and the limited budget. Decorative detailing

is used to emphasize openings, projecting elements, and as is

traditional, in places where the building is touched.

Structures, Materials, Technology, Construction

Most of the on-site labor was unskilled

and local, and the construction low-technology. The housing units

were built using post and beam construction because of the water

table, with hollow concrete or cored terracotta brick walls.

The floors were constructed of brick filler blocks covered with

concrete and paved with terrazzo tiles. Exterior walls were of

painted render. Units were standardized to facilitate design

and implementation. The suq was designed with a concrete frame

supporting concrete vaults, its structural frame allowing for

flexibility in the position and size of the shops. In situ concrete

was used for structural members, the exterior walls and internal

partitions.

In the Hafsia II project wide bands of

glazed ceramic tiling were used to articulate doorways, and decorate

facades. The technical assessor for the 1995 Aga Khan Awards

drew attention to the way that the Hafsia II project still used

low-technology construction methods by local unskilled labor.

The restoration of old buildings depended on their original structural

system, but most required reinforcement with new concrete members.

The historical restoration work was carried out by skilled artisans.

Current State

In the Hafsia I project, the offices

envisioned were not a success. The units became dwellings or

storage spaces, but the reconstruction did still result in a

vigorous commercial life in the quarter.

By 1978, only a year after completion,

80% of the wealthier inhabitants had already modified the plans

of their houses, by moving or removing partitions, moving doors,

and rearranging storage areas. Sixteen percent of the units had

been divided into smaller independent housing units, 25% of the

inhabitants had extended their houses by up to 3 additional rooms,

and 31% of the units were shared by two or more households.

The architects had anticipated and made

some allowance for alterations, but not on this scale. Neighbors

argued over sunlight, views, and ventilation. The high level

of rebuilding is a problem resulting partly from the fact that

actual residents of the area are wealthier than was anticipated

by the original surveys and planned for in the scheme.

The houses were not allocated to the original

residents of the area or to the most needy, so the wealthiest

from neighboring communities moved in. Occupants are mainly shopkeepers,

artisans, white-collar workers, executives and professionals.

Electrical and telephone cables have proliferated

across the streets and along walls. Inhabitants were impatient

for the official connections, some only promised by 1983, which

they did not consider a reliable promise.

After the Hafsia II project, the revitalization

of the area became more clearly visible, both physically and

culturally. The significant improvement in living conditions

and subsequent improvement in the areas' image has attracted

more business, to the point were traffic congestion is a real

problem. Property values have increased and developers have bought

housing with the intention of creating commercial sites. Private

ownership of property in the Hafsia had reached 80% in 1995.

AUTHOR'S CONCLUSION

The aim of the first stage of rehabilitation

was to reconstruct a residential and commercial sector of the

medina of Tunis that would retain the character of the old city.

They wanted to maintain a harmonious relationship with the existing

architecture and at the same time provide suitable housing for

the poor from neighboring areas, although it completely failed

to fulfil this second aim.

The project won an Aga Khan Award for Architecture

in 1983, "for a noteworthy attempt to deal with the problem

of urban public housing in a sensitive and humane fashion. The

Hafsia quarter represents a considerable effort in achieving

the scale of the old medina, sensitively inserting new 'infill'

housing into the urban tissue of the medina. On the other hand

the project is surely flawed: physically in its detailing and

execution, socio-economically in its inability to cater for the

needs of the lower income residents of the medina."2

A main aim of the Hafsia II project was

to learn from the mistakes of the first project, and this is

obvious in some of its principles. All architectural, urban,

socio-economic, demographic, and employment data were to be simultaneously

taken into consideration to produce integrated projects. User

participation was to be encouraged by giving financial and institutional

incentives for private owners to undertake renovation. Renovation

areas were to be surrounded by rehabilitated areas, and not adjoin

derelict areas. As few as possible of the urban poor already

living in the area were to be displaced, with the incoming, more

affluent, residents paying a higher share of the costs. To promote

the spread of such rehabilitation projects, appropriate funding

and agencies were to be set up, and the cost recovery of expenses

maximized. Hafsia II combined the sale of property to private

developers with the cross-subsidization of rehabilitation loans

for the deteriorated residential structures.

Hafsia II rehabilitated the area surrounding

the new interventions of the 1970s, and aimed to minimize their

contrast with the existing architecture. A main goal was to retain

the resident population, with a reduction in population density

to ensure each family at least 40 square meters of living space,

including a bathroom, water supply and kitchen. This project

also won an Aga Khan Award, in 1995, in the social category for

projects that "enrich the international debate about the

problems of rapid urbanization, historic cities, and the problems

of a growing underclass."3 The Jury praised the scheme for "having revived

the socioeconomic basis of the old medina while respecting its

unique scale and texture. The Hafsia district is once more a

vibrant locus institutional success, community involvement, financial

and economic viability, excellent public-private partnership

and a programme for the displaced make Hafsia a success worthy

of widespread study."4

THE PLAYERS

Hafsia I:

Clients: ASM acting for the municipality

of Tunis, with help from

UNESCO, and homebuyers of the quarter.

Architects: Arno Heinz, Wassim Bin Mahmoud, Serge Younsi, Serge

Santelli, Michel Steinbeck

Planner: Jelal Abdelkafi, ASM

Developer: Societé Nationale Immobilière de Tunisie

(SNIT)

Hafsia II:

Client: Municipality of Tunis, through

ARRU

Architects: ASM, Achraf Bahri-Meddeb, Amor Jaziri, Samia Akrout

Yaiche

Coordinator: Denis Lesage

Developer: ARRU

FINANCING

The Government of Tunisia and the World

Bank financed both stages of the rehabilitation. Hafsia II utilized

realistic and successful schemes for maximizing economic potential.

A guiding principle was that the new residents with the highest

incomes should subsidize the rehabilitation and the reduction

of population densities in the old housing.

Rehabilitated buildings were exempt from

real estate tax as an incentive for the original occupants to

remain, and 120 of the 400 new housing units were also exempt

from real estate tax to accommodate those whose houses were demolished

or the number of rentals reduced as part of the project. However

the real estate tax for the remaining new units included the

overall costs of roads, demolitions, indemnities paid to those

evicted, and a surcharge intended to finance rehabilitation of

old houses, with shops, offices, and middle-class apartments

having the highest surcharges. The rates of return on investment

have been high.

Endnotes

1. Peter Eisenman quoted from the 1995

Aga Khan Award Master Jury's debate in Architecture beyond

architecture: creativity and social transformations in Islamic

cultures: the 1995 Aga Khan Award for Architecture, ed. by

The Aga Khan Award for Architecture, (London: Lanham, Md.: Academy

Editions, 1995).

2. Master Jury's citation for the 1983

Aga Khan Awards in the unidentified article from Hasan.

3. Quotation from the Master Jury's debate

on the 1995 Aga Khan Awards in "Reconstruction of Hafsia

2," Architecture beyond architecture: creativity and

social transformations in Islamic cultures: the 1995 Aga Khan

Award for Architecture, ed. by The Aga Khan Award for Architecture,

(London: Lanham, Md.: Academy Editions, 1995).

4. Quotation from the Master Jury's debate

on the 1995 Aga Khan Awards in "Reconstruction of Hafsia

2," Architecture beyond architecture: creativity and

social transformations in Islamic cultures: the 1995 Aga Khan

Award for Architecture, ed. by The Aga Khan Award for Architecture,

(London: Lanham, Md.: Academy Editions, 1995).

Bibliography

Association de sauvegarde de la médina

de Tunis. Le Project Hafsia, à Tunis. L'Habitat

Urbain Contemporain dans les Cultures Islamiques. AKPIA.

Davey, Peter. "Hafsia Quarter, Medina

of Tunis, Tunisia." Architectural Review. v. 174,

no. 1040 (October 1983).

Ferretti, Laura Valeria. "Pilot Schemes

for Tunis." VIA. v. 6, no. 23 (September

1992).

Huet, Bernard. "The Modernity in a

Tradition, the Arab-Muslim Culture of North Africa." Mimar.

no. 10 (October-December 1983).

Kafi, Jellal El. "Tunisia: Hopes for

the Medina of Tunis." The Conservation of Cities.

New York: St. Martin's Press, 1975.

Vigier, François. Housing in

Tunis. Cambridge: GSD/Harvard University, 1987.

"Hafsia Quarter, Medina of Tunis,

Tunisia, 1977." Mimar. no. 10 (October-December 1983).

"A New Neighbourhood in an Old Pattern."

Architectural Record. v. 171, no. 11 (September 1983).

"Aga Khan Awards." Architectural Review. v.

198, no. 1185 (November 1985).

"Reconstruction of Hafsia Quarter

2." Architecture Beyond Architecture. Aga Khan Award

for Architecture, Academy Editions, 1995.

"The Aga Khan Award for Architecture."

Arts and the Islamic World. v. 1, no. 3 (Summer-Autumn

1983).

"The 'Hafsia,' Tunis." Mimar.

n. 17 (July-September 1985).

"The Second Aga Khan Awards: Still

an Incomplete Voyage." Progressive Architecture.

v. 64, no. 10 (October 1983).

Illustration Credits

1. Aga Khan Award.

2. Photo by Khadija M'Hedhebi, Aga Khan

Award, 1995.

3. Photo by Khadija M'Hedhebi,

Aga Khan Award, 1995.

4. Aga Khan Award, 1977, ASM.

5. Aga Khan Award,

1977, ASM.

6. Aga Khan Award, 019 tun 28 fr. 5651.

7. Aga Khan Award, 019 tun 206

fr. 5669 k12724.

8. Photo by Ranta

Fadel, Aga Khan Award, 1995.

9. Aga Khan Award, 1977, ASM.

10. Aga Khan Award, k12706,

Mimar 17, 1985, AFSM.

|

1. Plan of the Hafsia quarter showing the two phases of

rehabilitation.

2. Street view, phase 2.

3. Street view, phase 2.

4. Interior of souk, phase I.

5. View of souk and new housing beyond, phase I.

6. Street view, phase I.

7. Interior of a bedroom of a restored house, phase I.

8. Window showing decorative detailing, phase II.

9. Roofscape, phase I.

10. Elevation of new housing, phase II.

|