|

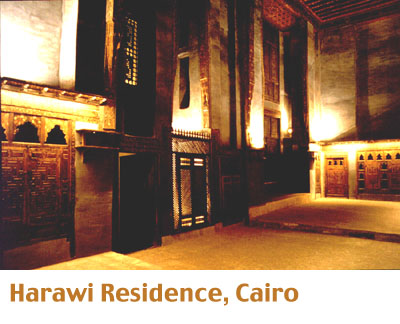

Historic Restoration of Harawi Residence

Cairo, Egypt

Anna Bardos

INTRODUCTION

The Harawi residence is a private

house situated in the heart of one of Cairo's most architecturally

rich quarters, near to the Al-Azhar Mosque. The building as a

whole was built in 1731, but it also contains a large reception

room dating from the 16th century, and a later addition of a

secondary entrance from the 19th century. It was restored between

1986 and 1993 by the Mission for Safeguarding Islamic Cairo and

the architect Bernard Maury.

CONTEXT

Historical

The Harawi residence

is known by the name of one of its last owners, Muhammad Harawi,

who occupied it in the first half of the 19th century. The building

was significantly modified at that time, but luckily the most

important rooms survived this period of modernization. The building

was acquired by the Egyptian Committee for Conservation of Monuments

of Arab Art at the beginning of the 20th century.

In 1970 a research mission was

set up called the Mission of Scientific Study of the Palaces

and Houses of Cairo of the 14th to 18th Century. This was an

initiative of the Centre Nationale de la Recherche Scientifique

(CRNS) and the French Foreign Affairs Ministry, in collaboration

with the Egyptian Antiquities Organisation. In the early 1980s

Dr. Ahmed Qadi was the head of the Egyptian Antiquities Organisation.

He instituted a new policy of restoration and safeguarding of

important buildings, which led to many projects.

In 1984, at the request of the

Egyptian Antiquities Organisation, France created the Mission

for Safeguarding Islamic Cairo with the objective of restoring

a monument. France was to provide two experts, and Egypt was

to provide the labor and materials. Architect Bernard Maury was

chosen to direct the project.

The Harawi residence was chosen

in 1985 out of six buildings in Cairo under consideration for

restoration. Criteria justifying the choice included the significant

architectural, archeological and historical value of the building,

its relatively unaltered state, and its privileged position in

the heart of the urban fabric.

Due to the knowledge acquired

of the domestic architecture of Cairo during more than 15 years

of research, the Mission of Scientific Study of the Palaces and

Houses of Cairo was able to propose a method for the restoration

and to commence work quickly.

THE PROJECT

Spaces and Uses

The mostly three-story

house consists of a number of rooms built around a main courtyard.

(Image 1) The original entrance to the building is from the south,

through a passage off the alley Zuqaq Al-Qasr (1). As in all

houses of this era, the access to the court is crooked to preserve

intimacy. The central court (9) is open to the sky and provides

access to all parts of the building. A second entrance to the

north of the court was added in the 19th century, accessed from

Zuqaq al-Ennabi, and is the one more frequently used.

The mandara (16) to the

east is, as is traditional, divided into three separate spaces.

The central space has an octagonal basin of mosaic in the floor,

with ventilation through a lantern 14 meters above. Another reception

room, the salon, (12) to the south of the central court is decorated

in two styles Cairene, with geometric patterns, and Turkish,

with floral patterns. The ceiling in this room bears the date

1731. Other rooms on the first floor include kitchens, outbuildings

and storage spaces.

The second floor is mainly occupied

by private apartments, which are accessed by one stairway to

the west. The Qa'a (35) is a beautiful traditional room,

with floral decoration and plastered walls of slate blue. The

rooms 37, 38 and 47 are similarly decorated, rooms 42 are from

the 19th century and of less interest.

Structures, Materials, Technology,

and Construction

The foundations of the

house are of quarry stones and rubble held together with earth

mortar. They are laid in trenches dug into the ground, with the

greatest depth being 1 meter and the width varying between 600

to 800 centimeters. These were found to be in fairly good condition

at the outset of the restoration work, and not too affected by

water.

As a general rule, the ground

floor walls are faced with dressed stone, and the higher levels

are of plastered brick. The filler between the stone facings

is rubble and debris held together with a mixture of lime and

earth.

The floors are constructed in

the traditional manner of a line of joists, which hold the floor,

covered with a bed of filling material 150-200mm deep as the

setting for flagstones. Lime mortar, about 50mm deep, and stone,

also about 50mm deep, is used for the floor. The ceilings are

constructed in the same manner as the floors, but the beams are

carved and the exposed underside painted. Roofing also uses this

construction method, but the stones are thinner and are waterproofed.

CONSERVATION OBJECTIVES AND

OUTCOMES

A principle aim of the Harawi

house project was to save an Islamic building of Cairo and to

try to create more momentum in this direction. The restoration

of the Harawi residence is seen as a 'work-school' for the learning

of traditional skills. The completed project can be seen as a

reference tool for future projects. Throughout the duration of

the work, the Mission pursued the goal of educating the workmen.

Great progress was made in the

aim of reintroducing traditional construction methods, and in

training artisans who could then use their skills elsewhere.

The necessity of bringing in external qualified labor for more

specialized restoration work resulted in many of the unskilled

workers acquiring experience, skills, and even qualifications

themselves.

The second positive result of

the project is the successful integration of the building into

the social life of the quarter, and its wide range of visitors.

The quarter has become cleaner around the Harawi residence, and

the government of Cairo has made efforts to improve the quarter

with new streetlights, resurfacing of certain buildings, and

the regular removal of household waste.

CONSERVATION PROGRAM INTERVENTIONS

A main concern was to respect

as much as possible the materials used in the original construction,

so stone, brick and wood were used according to traditional practices.

The use of lime was reintroduced, as too often it is abandoned

in favor of cement with a detrimental effect on old buildings.

All the materials used originated locally, and were often salvaged.

To assure the same quality of stone for the floors, pieces were

acquired from old buildings being demolished. Wood was also found

in this way. Only the bricks used were of present day manufacture,

and these were covered by plaster.

It was essential that all the

work be manual, and so there were no mechanical appliances or

lifting gear on the site. Of the labor involved, 20% was specialized,

such as that for the restoration of joinery or paintings and

80% non-specialized, with 90% of all labor described as native.

In the basement, some stones

had been damaged by humidity and deteriorated through lack of

maintenance. The availability of specialized local labor and

materials meant it was possible to replace defective stones without

the wall above failing a technique that was also utilized

in other areas of Cairo.

The façade on the south

of the court showed signs of profound modification since its

original construction. Under a pointed arched door dating from

the 19th century were signs of a fanlight, and signs were found

of a large square bay window that had been blocked up and replaced

by three pointed arched windows. Also, traces of a rectangular

opening were found to the right of the door, at a high level.

When these indications were verified

by further investigation, it was decided to reinstate both windows,

and replace the door. In the process of taking out the wall filling

to reopen the bay window, pieces of a carved door were found

that had been used to block up the opening, enabling the original

18th century door to be reinstated.

The façade on the west

of the court showed two phases of construction to the left

is a carved stone doorway from the 18th century, and to the right

side are pointed arched windows from the 19th century, built

when the new north entrance was added. The older doorway was

collapsing due to aging of the mortar, so in the conservation

process it was taken apart and reassembled with new mortar, then

micro-sandblasted to restore the original color of the stone.

The newer part of this façade required serious restoration

only to the joinery.

The façade to the east

of the court required much restoration at balcony level, with

a complicated task of repairing the beams before waterproofing

under the flagstones. The salon (12) required important restoration

work to the ceiling that was carried out once the bays were reopened.

The ceiling was in very poor condition, with some beams broken.

It was strengthened by sliding metal structures into the ceiling

and the main beams. In this way they were able to avoid making

the additional structure visible.

The Qa'a above the salon

had a particularly broken up floor, and was also open to the

sky as the center of the ceiling was missing. The ceiling was

closed off by an octagonal element, recalling the lantern of

the mandara. The painted ceilings were carefully restored

and then appropriately lit.

The mandara was missing

its lantern and so this was replaced. The murals were restored,

and missing elements of joinery replaced. Also, the entrance

to the room was moved to its original position as this had been

altered at some stage.

The building's wooden screens

and balconies were waterproofed and protected by tarring. All

external brick construction was re-coated with lime plaster.

Since its inauguration the house

has been used to hold seminars, exhibitions, concerts and dinners,

in both the salon and the mandara.

SCHEDULE OF CONSTRUCTION

1986: Work starts with the restoration

of the building's stone basements. Organizing the work, and more

significantly, the delivery of materials caused much delay, so

that the work did not resume normal speed until the start of

1988.

1987: Ongoing repair of the structure

of the building until 1991 including: repair of brickwork, vital

work on both levels in the west zone of the dwelling, reinforcement

of the floor in the Qa'a and room 37, repair and waterproofing

of the balconies to the east and south of the dwelling, restoration

of the lantern of the mandara, and restoration

of the 19th century parts of the building.

1990:

February: Study of the lighting of the building.

1991:

February: Electric cabling installed.

March: Start of lime coating, and a first test of the restoration

of woodwork, yielding inconclusive results.

November: First attempt to restore the paintings through

the CRETOA d'Avignon.

1992:

January: Trial illumination of the house, which proved encouraging.

March: The second mission to restore the painted ceilings, which

took one month.

October: Sandblasting of stone walls, which took until June 1993.

1993:

January: Final electrical installation.

April: Final internal plastering.

June: Lamps installed.

August: Final laying of flagstones.

September: Verification of last details.

September 25th 1993: Inauguration

of the house.

THE PLAYERS

Centre National de la Recherche

Scientifique (CRNS)

French Foreign Affairs Ministry

Egyptian Antiquities Organization

Mission for the Scientific Study of the Houses and Palaces of

Cairo

Mission for Safeguarding Islamic Cairo

Bernard Maury, Architect

FINANCING

Labor $ 177,710

Materials $ 90,361

Professional consultants $ 530,120

Other costs $ 212,350

Total cost $ 1,010,500

Cost per square meter $790

This cost per square meter is

described as average for work of this kind. Eight percent of

the total funds came from private sources, and 92% from public

sources. None of the public funding was described as from local

sources, 30% came from national sources and 60% from international.

The labor was provided by the Egyptian Antiquities Organisation.

Bibliography

Maury, Bernard; A. Raymond; J.

Revault; M. Zakariya. Palais et Maisons du Caire II, Epoque

Ottomane, XVI-XVIII siecles. Paris: Editions du Centre National

de la Recherche Scientifique, 1983.

Maury, Bernard. Aga Khan Award

Project Record, 20th January, 1998.

Illustration Credits

1-8. The Harawi residence, Images

1 8: Aga Khan Award for Architecture archives, Bernard Maury.

9. Rotch Library Visual Collections, MIT, Cambridge, MA, "Plan

of Islamic Monuments, 966-1945, detail of north half, east side."

10 - 13. Maury, Bernard; A. Raymond; J. Revault; M. Zakariya. Palais

et Maisons du Caire II, Epoque Ottomane, XVI-XVIII siecles.

Paris: Editions du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique,

1983.

|