|

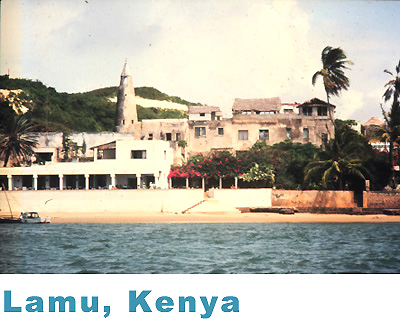

T. Luke Young INTRODUCTION Lamu is a historic town with a rich history and texture increasingly threatened by modern interventions and the loss of its traditional socio-economic base. The town has prospered and declined in waves over time and is now a serious conservation challenge due to the developments of the last two decades: lack of maintenance, population increase and expanding numbers of tourists. Two conservation plans have been written in an effort to overcome these negative effects and benefit the community. The first in 1976 was in many ways a baseline survey that began to lay the foundation for preservation planning. It resulted in the identification and preservation of a few isolated monuments. Perhaps more importantly, it raised awareness and heightened the prominence of cultural heritage in Lamu and also in Kenya. (Fig 1.) The passage of the Antiquities and Monuments Act in 1983 spurred the community and government agencies to work with the National Museums of Kenya and to carry out the subsequent Lamu Conservation Plan completed in 1986. This plan proposed creating a conservation area and dictated how land could be used in the town to ensure sensitivity to the historic fabric of Lamu. Illustrated building regulations provide a how-to guide for homeowners who wish to alter their existing house or build a new one within the historic district. The plan was a well-crafted document that served its purpose boldly. It remains to be seen whether or not its noble, yet pragmatic, intentions will be enough to withstand the powerful forces of the contemporary economy and tourism development. CONTEXT Historical Perspective The Swahili town is the joint product of trade and Islam. The first provided wealth, the second provided the incentive for settling since in Islamic law it is stipulated that the Friday noon prayer be held in a permanently settled location. The monsoon winds supplied the energy the ships needed and building materials, coral and mangrove, were available on the shores. The preferred sites for towns were on islands that were protected from external attacks. One of the city-states founded by Arab travelers was located on the island just off the northern coast of modern Kenya, called Lamu. While there were certainly earlier settlements on the island, the present town site is not likely to be much older than the 14th century. Lamu town flourished as an independent city-state until 1506 when Portuguese traders, seeking to control a lucrative market with the Orient, invaded. Over the course of the 16th century, the once prosperous Swahili town lost its middleman position and gradually declined. Resistance to the Portuguese was finally successful with the help of the Turks and in 1698 the last forces surrendered. The Omani's who had helped overcome the European invaders now became the dominant force in the region. Under Omani protection, coastal commerce slowly regained its former momentum. The commercial revival stimulated a resurgence of building all along the coast, and it was during this period that Lamu's inhabitants built most of the traditional stone houses and mosques still standing in the old town today. They used the coral stone and mangrove timber from the archipelago, employed skilled craftsmen from India and brought slaves from the interior. The island remained prosperous for over two hundred years until the late 19th century when the British began to take an interest in East Africa. They forced concessions on the ruling Sultan and the East Africa Protectorate was established in 1895. Lamu town became the headquarters of Lamu District, administered by a resident British official together with a Muslim official. Agriculture had been the most important economic activity for Lamu, but its plantations withered after proclamations made the procurement of slaves increasingly difficult and expensive. The introduction of the Uganda Railroad stretching from Mombosa to Lake Victoria in 1901, left Lamu somewhat isolated. As the railroad's terminus Mombosa became the main seaport of the East African coast, relegating Lamu to a minor role as a small local harbor. With neither trade nor agriculture to support the economy, Lamu stagnated, and by the mid-1920s was in a full-scale depression. Population in Lamu District fell more than 40 percent. Lamu drifted into economic obscurity, as a small, remote island town. It was the town's isolation from 20th century modernization that preserved the rich architectural heritage still extant today. Mangrove exports, commerce, and government jobs coupled with traditional maritime activities have provided a stable economic base for the growth of the town since the 1960s. More recently, an increase in tourism has contributed an additional source of revenue. The rapid population growth coupled with an increased awareness of cultural heritage led government officials and residents to undertake a conservation study of Lamu town in the early 1970's. THE PROJECT Planning Context The recommendations were accepted and funds approved through the National Museums to carry out the studies. Writing a report, the first phase, was finished in 1976. It consisted of surveys, an analysis and evaluations, and recommendations on the conservation needs of Lamu town. Following this study many monuments were identified and restored, but it was only with the passage by Parliament in 1983 of the Antiquities and Monuments Act that Kenya finally had the all-important legal framework to safeguard its cultural heritage sites. After two years of cooperative study between the Lamu community, the Department of Physical Planning, the Ministry of Local Government, and the National Museums of Kenya, the Lamu Conservation Plan was published in 1986.1 The plan put forward a clear and constructive statement of how best to protect and enhance an outstanding example of cultural heritage. The philosophical approach was that conservation is not antithetical to progress, but that by rooting development in the past, it is possible to provide direction and a firm base for the future. Richard E. Leakey, Director of the National Museums of Kenya, writes in his introduction to the plan that, most of all, conservation can help prevent the indiscriminate exploitation of our resources and create a better environment for all. CONSERVATION APPROACH The conservation program set out to accomplish specific aims by proposing answers to a series of questions: What is the role of the old town in Lamu, and what problems will it face in the future? Can better planning and conservation of the historical area solve these problems? If so, what kind of strategy should be pursued to plan and preserve the old town? Finally, what can be done to promote balanced development of the entire town and accommodate its projected growth in the years to come? As a starting point, the authors of the document stressed the need for a plan. The importance of the old town was clearly illustrated. More than five hundred stone buildings standing within its boundaries represented almost thirty percent of the total number of structures in the town and housed over one third of Lamu's population. Neglect and decay on one side and new construction and radical alterations on the other threatened the structures. The plan emphasized that the greatest threat to historic Lamu town was posed by unregulated new construction. Without the buildings, streets, and public spaces of the old town, Lamu would forfeit both its social center and its cultural identity. Strategies The plan recognized that while the conservation of the old town was important, it would not solve all of Lamu's problems. The old town could not be isolated from the ring of new settlement that surrounded it and is expected to have a population of 30,000 by the year 2000. Strategies to develop a new settlement used for those departments that would be more efficient if located on the mainland would provide a social, administrative and commercial center for the surrounding agricultural area. The planners felt that this strategy would help to preserve and improve the historical area. In the long run, preservation and balanced development of the old town would be impossible without a strategy of controlled growth for Lamu town as a whole. Preservation Policies Additionally, the plan recommended improving the infrastructure. Strategies for upgrading water distribution networks, open drain systems, pit latrines and electricity supply were recommended in the report. Establishment of an administrative procedure for ensuring the implementation of the above mentioned preservation policies and service upgrades was proposed. The procedure outlined an application and approval process for building in the old town and the establishment of a local commission with a supervisory board was suggested. Plans and drawings pinpointing the designated land use areas and illustrating proposed design schemes augmented the document. Three special projects, The Seafront, The Town and Market Square, and The Fort were detailed in their own section of the plan. Perhaps most constructively, the plan concluded with a section on building guidelines. They were written to provide technical advice on common problems in caring for and adapting the traditional stone houses of Lamu. Descriptive paragraphs supplemented with design and construction details covered many possible modifications, from improving doors and windows for ventilation to the disposal of household wastewater in the kitchen.2 AUTHOR'S CONCLUSION The plan was well written and provided a constructive and realistic framework for conservation in Lamu town. Yet, it failed to address financial issues relating to conservation regulations set forth by its implementation. No current data could be located to accurately assess whether or not the plan or parts of it had been implemented since its publication in 1986.3 Personal accounts of tourists who recently visited there confirm that the economy is heavily dependent on heritage tourism.4 Foreigners are now buying up traditional stone houses at an alarming rate, disrupting the balance of a locally oriented economy. Additionally, plans for the improvement of a land road, the building of a harbor and the improvement of the airport are likely to add further difficulties which the Lamu community will need to confront as it seeks to maintain its cultural heritage.5 The town has not been nominated to the World Heritage List, nor has Kenya signed the World Heritage Convention. While this may not seem to bode well for conservation efforts in the town, it is important to remember that Africa is going through a process of change and it will take time to develop a conservation ethic in the region. The guidelines in the meantime are of great importance in providing direction for contemporary and future development. Lamu is preparing for substantial infrastructure intervention and now has the opportunity to implement the solid conservation plan it painstakingly developed over the last two decades. Time will tell how Lamu will deal with market forces, some might concede that it is already too late. But, the history of this East African Seaport is a story of survival in the face of invasion. It remains only up to the community whether they accept the loss of cultural heritage to be inevitable, or if they choose to guide development to sensitively respect the rich texture that is Lamu.

Endnotes 1. This case study was prepared with considerable help from Planning Lamu: Conservation of an East African Seaport for information on the history and policies of preservation of Lamu. It is this plan that is the primary subject of my investigation and analysis. 2. The plan ends with two appendices, one is a Historic Lamu Gazette Notice, and establishes the criteria for declaring a site a monument and for establishing a regulated conservation area. The second lists definitions related to building regulations. Following this section is a useful glossary of terms and a bibliography. 3. For information on the current state of conservation in Lamu try contacting: Mr. Omar Bwana, Dep. Director, National Museums of Kenya, P.O. Box 40658, Nairobi, Kenya, tel.: 742131/4 or 742161, telex: 22892, or fax: 741424. 4. Marco Magrassi, Urban Economist, discussed with me in an informal interview how droves of foreigners were buying up quantities of traditional stone houses for summer cottages. Because they use the dwellings for only three months out of the year the old town is left empty most of the time. This creates an imbalance in the delicate socio-economic system of Lamu. 5. The Organization of World Heritage Cities describes Lamu's conservation initiatives and challenges in its on-line conservation management guide. http://ovpm.org/ovpm/english/guide/cas/gec-lamu.html Bibliography Allen, J. de V. Lamu Town: A Guide. Lamu: J. de V. Allen, 1974. Ghaidan, Usam. Lamu: A study in conservation. Nairobi: The East African Literature Bureau, 1975. Pulver, Ann and Francesco Siravo. Planning Lamu: Conservation of an East African Seaport. Nairobi: The National Museums of Kenya, 1986. Credits All photographs and illustrations courtesy the Aga Khan Fund, MIT Rotch Collections, unless otherwise noted below: 5 & 6. Antonio Martinelli, Courtesy, Aga Khan Trust for Culture.

|

|

|

|