|

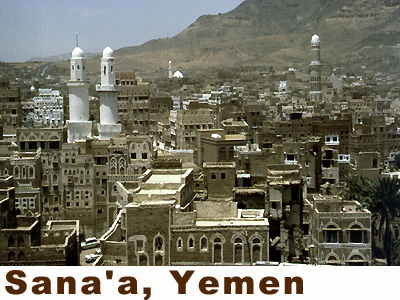

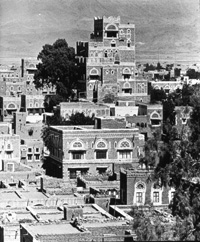

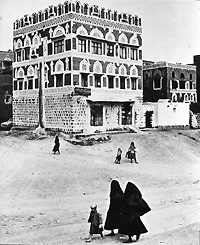

Conservation of the Old Walled City of Sana'a Republic of Yemen T. Luke Young "Viewed for the first time the old walled city of Sana'a creates an unforgettable impression, a vision of a childhood dream world of fantasy castles."1 INTRODUCTION Sana'a has been continuously inhabited for over 2,500 years. Its religious and cultural heritage is reflected in its 106 mosques, 12 hammams (bath houses) and 6,500 houses built before the 11th century.2 The city's architecture has been damaged, demolished and rebuilt through flooding, wars and prosperity. Yet, it wasn't until the modernization in the 1970s that the city's architectural fabric was truly in danger of disappearing. In the early 1980s, at the request of the Yemeni government, UNESCO launched an international campaign to conserve the city, which has been lauded world wide as a success. After considerable preservation and rehabilitation efforts, the city was designated as an UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1988 and given an Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 1995. While conservation efforts have been successful, little has been written to analyze the impact of the resulting tourism and development. CONTEXT Physical and Historical Sana'a is one of the most ancient surviving cities in Arabia and arguably the longest continually inhabited city in the world. By the first century BC Sana'a emerged as a center of the inland trade route. After the withdrawal of the Turks in 1630, Sana'a became the seat of an independent Imam. This ushered in a period of prosperity for the city, which lasted for nearly two centuries and can still be seen in the quality and quantity of buildings from that time. Most of the domestic architecture still standing in the city dates from this period and later, while the extant mosques reach back well over one thousand years and fragments of towers are as old as four centuries before the rise of Islam. THE PROJECT Traditional Buildings The streets of the city are flanked by towering houses five to nine stories high. The houses are constructed of ashlar stonework from six to ten meters above street level where exposed brickwork then takes over.4 In Sana'a the space between buildings is just wide enough for pedestrians and mule-drawn carts. Timber is in short supply since trees are

relatively rare and small and so the traditional architecture

of Sana'a relies on stone and clay bricks decorated with gypsum

plaster. Symmetrical balance is clearly a desirable characteristic

in the houses of Sana'a and facades have strong ingredients of

conventional formality. The opening of the country to the outside world in the 1970s, and the growth which accompanied the decision to make Sana'a the capital of the new Yemen Arab Republic, posed new challenges to the old city. The huge influx of dollars from the oil boom in neighboring Saudi Arabia, combined with a rapidly growing population, placed considerable stress on the old city's historic buildings and its inadequate infrastructure. Sana'a grew extraordinarily fast as oil workers returning home invested their money in property. The population grew from about 55,000 in 1970 to 250,000 in 1982.5 City growth by 1978 was out of control and with the new money came more automobiles. Urban Yemenis abandoned their houses because they could not afford to maintain them, and preferred new villas out of town. The main shopping, banking and government services shifted out of the old city, mainly to the west and northwest. Educational, recreational, entertainment and health facilities also moved away to an area outside the walls. Wealthier residents moved away due to the unsanitary condition of the streets, lack of services and the relative inaccessibility of their houses by vehicles. They relocated to areas that promised a modern lifestyle adjacent to new facilities. Lower income Yemenis moved in to the old city and conditions deteriorated. Economic development in Sana'a made the introduction

of modern construction technology unavoidable. New reinforced concrete

structures became eyesores alongside the traditional buildings.

Additionally they proved to have adverse effects on traditional

construction materials. Concrete's inflexibility cracked surrounding brick

and deposited salts that deteriorated the soft traditional materials (Fig.

3). As a result of modernization efforts in the old city, including the

introduction of water and sanitation systems without adequate drainage,

thirty historic houses collapsed between 1978 and 1979.6 In reaction to this grave state of ill repair, Yemeni officials and foreign technical advisors working in Sana'a pressed for the conservation of the city. They proposed that the whole town should be saved and that preservation challenges could be solved incrementally. The international community criticized this approach.7 The main idea was to promote a living city while balancing the needs of conservation and development. Ronald Lewcock, an active advocate of the plan, summed up the primary motivation behind this philosophy: "Its value lies not so much in the merit of the individual buildings, important though they may be, as in the unforgettable impression made by the whole an entire city of splendid buildings combining to create an urban effect of extraordinary fascination and beauty."8 CONSERVATION PROGRAM INTERVENTIONS UNESCO's conservation program stresses that expertise, fellowships, equipment and voluntary financial contributions are urgently needed from all sources if the campaign is to be successful. Since the early 1980s a campaign to restore

and upgrade the city has been ongoing under the direction of

the General Organization for the Preservation of Historic Cities

of Yemen (GOPHCY). The campaign as outlined in a UNESCO publication

presents a strategy for conservation with three main goals.9 Two, ensure the preservation and rehabilitation of the traditional way of life of the medieval city as much as possible for those who desire it, without stifling urban life or the population's desire for change and improved facilities. Three, create a simple method of implementation for every aspect of the preservation and conservation of the old city. The plan also provides typical examples of the architectural conservation necessary, strategies for reviving cultural traditions, a suggestion for a plan of action and preliminary financial estimates for the preservation and conservation of the old city. Implementing the Plan The Yemeni government has allocated $11 million to install and improve water and sewage systems and agreed to pave the city's streets and alley's with bands of black basalt and white limestone.10 Work on the mud walls of the cities started in 1987 and continues today, as does the rest of the program. A pool of skilled local labor has been set up for this purpose. Adaptive use projects have led to new functions for historic buildings, including a women's technical school, an art gallery, a craft center, and guest houses. Throughout the city, local owners were encouraged to renovate their houses under the guidance of GOPHCY. Work continued as Swiss, Italians and others renovated buildings for use as hotels, cultural centers and private residences. Both the public and private restorations have shown considerable sensitivity to the architectural features of Sana'a, incorporating traditional materials and construction techniques in the restoration process. New markets are now more accessible to vehicular traffic, thus boosting business and revitalizing the area's once sagging economy. Cultural life in the city has also improved with the addition of galleries and craft centers, which have encouraged the arts and provided employment for craftsmen. GOPHCY was successful in coordinating the efforts of governmental, bilateral and multilateral projects. It has helped improve the quality of life in old Sana'a thus earning the good will of the inhabitants, who have mobilized to continue the rehabilitation process. THE KEY PLAYERS The conservation program has demonstrated an excellent ability to combine the efforts of many parties, public and private, national and international, to implement various parts of the plan, all guided by a common principle.11 The Sana'a campaign worked, in part, because the President's office guided it.12 But, the support of the local population and the international community were probably also vital to the project's success. These were the key participants in the conservation of Sana'a: 1. President's Office FINANCING The bulk of the financing came from Yemen,

but foreign aid from international organizations such as UNESCO

and UNDP, as well as individual European countries and entrepreneurs,

were vital to the project. AUTHOR'S CONCLUSION Despite the successful conservation efforts in the old walled city, many problems remain unresolved, mainly traffic congestion, pollution and the removal and effective disposal of garbage. Preservation controls have been put in place but are not properly enforced. Perhaps the most bittersweet aspect of successful implementation of the plan is the growth of heritage tourism. The mixed blessing of tourism is that while it introduces new forms of revenue, it displaces residents and substitutes a locally sustainable economy with one reliant on foreign currency. There are considerable worries about the detrimental effects of tourism on historic sites from Uzbekistan to the United Kingdom. Its influence on Sana'a has yet to be properly analyzed. Such a study should be conducted soon to avoid returning to the dilapidated state of the city which preservationists faced in the late 1970s (Fig. 5). In the meantime, it is appropriate to recognize the victories of those who have been active in conserving the old walled city of Sana'a. The quality of life has improved, people have moved back, and the streets are now clean. In many ways the preservationists involved have solved what Michael Welbank calls the most intractable conservation problem today, the conservation of a cohesive high-quality urban area. In writing about the challenges of combining conservation and development in Third World countries he suggest that cities take a middle course where both interests come together in a "give and take" policy.13 It seems that Sana'a has accomplished this balance, ensuring that the city remains populated and, perhaps most importantly, enlisting the support and the interest of its citizens in the preservation of the past for future generations.

Endnotes 1. Ronald B. Lewcock, The Campaign to

Preserve the Old City of Sana'a, Report Number 3 (Paris:

UNESCO, 1986), p. 15. Bibliography "Aga Khan Awards." Architectural

Review. v. 198, no. 1185 (Nov. 1995): pp. 62-86. Davidson, Cynthia C., and Serageldin, Ismail, eds. "Conservation of Old Sana'a, Yemen." Architecture Beyond Architecture: Creativity and Social Transformations in Islamic Cultures: The 1995 Aga Khan Award for Architecture. London: Academy Editions, 1995. Kirkman, James S., ed. "City of Sana'a." Nomad and City Exhibition: Museum of Mankind, Department of Ethnography of the British Museum, World of Islam Festival 1976. London: World of Islam Publishing Co., 1976. Lewcock, Ronald B. Class Lecture for MIT Course 4.239. 19 November, 1998. Lewcock, Ronald B. The Campaign to Preserve the Old City of Sana'a. Report Number 3. Paris: UNESCO, 1986 Lewcock, Ronald B. The Old Walled City of Sana'a. Paris: UNESCO, 1986. "Organization of World Heritage Cities (OWHC), Sana'a, Yemen" Web Page. http://www.ovpm.org/ovpm/sites/asanaa.html "Organization of World Heritage Cities (OWHC), The World Heritage Cities: Sana'a." Web Page. http://www.ovpm.org/ovpm/english/cities/ns_sanaa.html Sergeant, R. B. and Lewcock, Ronald, eds. Sana: An Arabian Islamic City. London: World of Islam Festival Trust, 1983. Welbank, Michael. "Conservation and Development." Development and Urban Metamorphosis. Singapore: Concept Media Pte Ltd for the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, 1984. Credits All images courtesy of Aka Khan Program, MIT Rotch Visual Collection.

|

|

|

|