|

Eunice M. Lin INTRODUCTION Within the small province of Singapore a rich history and a dynamic present exist side by side. As 20th century development transformed Singapore into one of the largest ports in the world and one of the major financial centers in Asia, interest in conservation also grew. In the mid-1980's, projects were initiated to preserve the city's heritage and culture, specifically in its built form. Initial proposals for re-use of the Boat Quay began in conjunction with Singapore's Urban Redevelopment Authority's (URA) efforts to promote the value of conservation. On July 7, 1989 the Singapore River Boat Quay, in addition to nine other sites, was designated as a conservation area. Today the Singapore River hosts a number of adaptive re-use projects which have turned the area into one of the city's best known tourist spots, with restaurants and businesses housed in the restored traditional shophouses. Although the use of the buildings has changed, the original spirit, life, and intensity of activity of the Boat Quay has been kept alive. (Images 1a, 1b) CONTEXT Physical Climate Historical Modern Singapore was founded by the British in the early 1800's as a port to service their vessels as well as an obstacle to further Dutch settlement in the East Indies. The English hold on the island was established in 1819 through the rule of Stamford Raffles, Lieutenant Governor of Bencoolen and an agent of the British East India Company. Early in 1819 he signed an agreement with the local Malay Chief, agreeing to protect the island in return for permission to establish a British trading post there. Raffles was responsible for the development and layout of the city as set forth in his "Plan of the Town of Singapore." The plan "focused on the remodeling of the town according to principles which would facilitate public administration and maximize mercantile interest, inscribe public order in space, and cater for the accommodation of the principal races in separate quarters."1 Raffles' plan, though not completely implemented, had far reaching results, basically defining the urban fabric of the city as it still exists today. It is also an important document for addressing critical issues of public administration, order and economic growth in a rapidly growing and diverse colonial city.2 The population grew from the initial 150 Malay fishermen at the time of Raffles' first landing in 1819 to 10,000 immigrants in 1824. In 1826, as part of the Straits

Settlement, Singapore came under the control of British India.

By 1867, the Straits Settlement became a Crown Colony under the

Jurisdiction of the Colonial Office in London. As a port it played

a major role in the trade between Europe and East Asia, especially

after the advent of the steamship and the opening of the Suez

Canal in the 1860's. Prosperity attracted immigrants from around

the region, establishing the cultural mix that still characterizes

Singapore. The prosperity continued for decades, peaking from

1873 to 1913. 3 Social Singapore is one of the most cosmopolitan cities in Asia. In addition to the 75% of the population that is Chinese, there is a mix of the following ethnicities in large numbers: Peninsular Malays, Sumatrans, Javanese, Bugis, Boyanese, Indians, Ceylonese, Arabs, Jews, Eurasians, and Europeans. In addition, four major religions are represented: Buddhism and Taoism, Islam, Hinduism, and Christianity. Economic COMPARISONS In the 1980's, in light of rapid growth and development, the need for conservation became a great concern. With such a mix of cultures, the importance of maintaining a common heritage became an important issue. The government realized that the development of the last several decades had wiped out large historic areas and buildings, quickly changing the original fabric of the city in the desire for modernization. In his book, Living Legacy, Robert Powell presents the background to Singapore's great surge of conservation projects. In the preface he states that there was a growing awareness that the built heritage is an important component of a cultured and progressive society. In this book, I have recorded the results of this changing ethos...as a body of work, they form an impressive record in a nation seeking to conserve its past. In choosing a past, we say something about Singapore's evolving cultural identity.5 After providing examples of noteworthy conservation efforts, he ends with a warning of the reality behind all the conservation projects: though numerous, the quality of work is not high enough to maintain Singapore's heritage. Conservation is happening too quickly. In the process, authenticity is often a secondary consideration. There is a tendency to 'gut and stuff' the interior (Raman 1993). Insufficient time is being spent on properly analyzing, researching, documenting, and surveying old buildings. There is a temptation to simply tear out the interior, leaving only the facade, and then to rebuild with a concrete frame structure within the existing party walls. Many architects and engineers and their clients versed in modern construction processes are insensitive to the nuances of an old structure, unable to 'read' the building, to sense its inherent qualities. As a result, there is a tendency to over-conserve on the one hand, 'dressing-up' buildings in colors and details that are coarse and inaccurate, and on the other hand to create an overall blandness by erasing the patina of age.6 Though the author is basically

espousing a general conservation philosophy it is relevant here

because his observations are also specific to the conservation

effort going on now in Singapore. The Boat Quay is an example

of a positive conservation effort in Robert Powell's book, but

from the examples given it seems that it is also a place that

has suffered from the "gut and stuff" style. As a former

warehouse and industrial area, its dual role as historical site

and touristic site is at issue here. The colors and details that

now distinguish this area are not part of the authentic heritage

which the conservation efforts of the URA attempted to preserve.

There have been mixed reviews of the Boat Quay project, one local

paper called it "an unremitting row of watering holes with

a reputation for drunkenness and teenage catfights with little

to remind one of the 'toil and tears of the immigrant generation

of Singaporeans' who used to work on the river." (The

Strait Times, 24 January 1996.)7 Reactions like this bring into question

the appropriateness of the new uses inserted into the area. The Shin House located at No. 12 Blair Road is an example of a purely residential shophouse that was restored to an earlier state. The houses in this area were built in the 1930's after an influx of Chinese immigrants. They display a mix of Chinese, Malay, European and colonial elements. The area was identified as a conservation site in 1986. The owner of the house, Shin Choo Neo, had a particular interest in turn of the century architecture. She therefore made minimal structural changes and maintained the original spatial quality of the shophouse. Other changes to the house that were not compatible with the desired original appearance, such as a 1950's iron stairway, were removed. Some new elements such as patio doors were added to bring in light. Overall it is an example of restoration sensitive to both the desired appearance and the historical qualities of space and light characteristic of a shophouse. (Image 3 & 4) The story behind the area of Fort Canning Hill is tied to the many political power struggles that mark Singapore's history. The main barrack block was erected in 1926. When the British army withdrew in the 1970's the building was converted into a restaurant with squash courts. In 1989 the National Parks Board decided to renovate it for use by two performing arts groups. The building was renamed the Fort Canning Centre, new mechanical systems were installed, and the squash courts were adapted to make room for new theater facilities. The original character of the building was restored by removing grillwork over the facade's openings and adding windows and doors and other authentic details. Although its use has completely changed, this structure maintains its original character both on the interior and the exterior. THE PROJECT Significance, Role in the

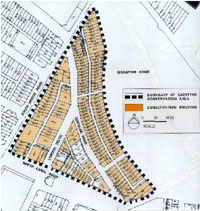

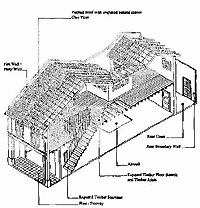

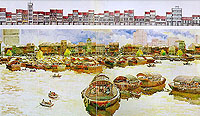

City, and Development By the 1860's, three quarters of Singapore's shipping business was transacted from the Boat Quay. Cargoes were carried from ships anchored in the roads to Boat Quay by lighters or tongkang. At its zenith in 1865, there were as many as 150 boats moored on the water, trading in everything from rubber, tin, steel, to silk, porcelain, rice, opium, spices and coffee.8 The area had various names, which were descriptive of its liveliness. The Chinese called it "Bu Ye Tian" meaning place of ceaseless activity. It also had the nicknames of "Tiam Pang Lo Thau," place to go for sampans, "Chap Poet Heng ,"the eighteen houses, and "Chwi Chu boi," bathing house end. (Image 5) In conjunction with growing governmental concerns for the conservation of heritage in the built environment, William Lim Seiw Wai and Dr. Goh Poh Seng developed a conservation proposal for the Boat Quay area in 1982. Though the proposal was not implemented, their basic ideas for converting it to restaurant and commercial use were similar to the resulting re-use project results. The proposal was a comprehensive scheme addressing the whole area as opposed to the way that the area was actually conserved, in a piecemeal fashion, building by building. In 1983 as part of the government's efforts to clean up the river, the remaining shipping industry's lighters were moved to a new site off Pasir Panjang. The presence of the industry had already begun to dwindle with the introduction of the more efficient and safe mechanized container port at Tanjong Pagar. Thus, from 1983 to about 1990 the Boat Quay was empty and unused. Once the area was designated a conservation area in 1989, redevelopment began and by 1993 every shophouse was under reconstruction. Physical Description The shophouse is a traditional architectural form in Singapore, and a building type indigenous to South East Asia, with its origins in the Chinese provinces and influenced by European colonial architecture. Typically they were used for businesses at the ground level and had living spaces on the upper floors. Spatially they are narrow, small and terraced, having exposed timber structure and staircases and a masonry party wall. Being only 6 meters wide, the resultant depth of the building's interior was opened up by internal open-air courtyards. The distinctive five foot covered walkways that line the quay and form a continuous path along it are actually a remnant from Raffles' original plan's concern for public spaces and pedestrians. As well as providing shelter from bad weather, these spaces, which were required on all houses on both sides of the street, were also used by minor random tradesmen such as fortune-tellers, barbers, medicine men, and traveling foodsellers.11 Structures, Materials, Technology,

Construction Current State For example, in The Opera Cafe at No. 40 Boat Quay the interior was dramatically changed to create an ambiance similar to an opera stage set. On the other hand, the Lim Family Shophouse, No. 58 Boat Quay, is actually a shophouse that has stayed within the Lim family since 1908. The ground level that once housed a warehouse space has now been transformed to house a Japanese restaurant. The uppermost floor has been retained as weekend living spaces for the Lim family. The architect Mok Wei Wei opened up the space by removing some of the original partition walls but for the most part such things as the original teak floors, paint color on the window frames, wooden balcony doors, and tile roofs have been restored and maintained. All original blackwood furniture and art pieces were restored and used as well. (Image 9, 10a, & 10b) Located near the business district, the Boat Quay is frequented by office workers and professionals during the day and at night becomes a popular hotspot for tourists and yuppies alike. It has become a much publicized area with everything from restaurants with outdoor dining areas to a cyber cafe. One web page advertising popular restaurants in Singapore has this to say about the Boat Quay: "Now it's the biggest tourist trap in Singapore since the Old Bugis Street queens once ruled the night. Stroll down the quay on a Friday or Saturday night, smell the heady mix of beer and cigarettes...On weekends it's a human zoo, but the area is not without its charms. The Boat Quay actually offers some of the best dining in Singapore, despite the extravagant prices."12 (Image 7) Another local web page echoes the same message, "The new developments along the river will form the backdrop for Singapore Tourism Board's plans to develop the river as one of the thematic zones in the near future...Now Boat Quay and Clarke Quay are renowned internationally as Singapore's hottest dining spots and the hub of Singapore night life."13 CONSERVATION PHILOSOPHY Singapore's efforts in conservation really began in the 1970's in response to the overwhelming amount of development that was occurring and the consequent obliteration of its historic built structures. In 1989 the Planning Act was amended to establish a definitive approach to conservation. As defined within the act, conservation was stated as: "the preservation, enhancement or restoration of: a) the character or appearance of a conservation area, b) the trades, crafts, customs, and other traditional activities carried on in a conservation area."14 More specific definitions can be found in the Urban Redevelopment Authority's internet home page. The important message that the web page seems to advocate is the three R's of "maximum Retention, sensitive Restoration and careful Repair." They also state that high quality restoration involves more than just the external appearance of the building and should address the "inherent spirit and original ambiance of historic buildings. It requires an appreciation and understanding of the architecture and structure of traditional buildings, good management and practice."15 Therefore, the documentation and research of existing conditions as well as of the whole process of conservation is also stressed. The URA's stringent guidelines for conservation are based on the principles set out in the Venice Charter, the International Charter for Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites. (ICOMOS, Venice, 1966) The principles established in Venice were integrated with relevant local concerns to develop today's current guidelines. The overall objective of the URA seems to be to maintain the cultural heritage while keeping economic growth alive. Consequently, a large number of the non-residential conservation projects are also expected to produce an economically viable end product in combination with maintaining a portion of their heritage. CONSERVATION PROGRAM INTERVENTIONS Phases of the Renovation Effort The actual phases of conservation began with the designation of the area in 1989. This act was the first of five phases in the URA's conservation efforts for Singapore. After that point it seems that all conservation projects within the Boat Quay area were individual initiatives carried out by private owners and architects. Structural Changes to Spaces

The entire building must be conserved.

Change of use to commercial use is allowed. The following may

be introduced: a new jack roof, skylight at the rear slope of

the main roof and on the secondary roofs, a roof mezzanine within

the existing building envelope, a cover over the rear court,

new windows on the rear facade and the gable end wall. Addition

of secondary doors and windows.17 The main player is the Singapore Urban Redevelopment Authority, which set the stringent guidelines for restoration and is the governing body that also approves conservation proposals. After that it seems each shophouse within the quay has been conserved individually by private owners. FINANCING

1. Marin Perry, Lily Kong and

Brenda Yeoh, Singapore: A Developmental City State, (London:

John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1997), pp. 26-27. Bibliography Balachandrer, S.B., ed. Singapore 1997. Singapore: Ministry of Information and the Arts, 1997. Jayapal, Maya. Old Singapore. Singapore: Oxford Press, 1992. Larson, Carl G. "Adaptive Reuse: Singapore River." Mimar. no. 12 (March 12, 1984): pp. 32-39. Perry, Marin; Lily Kong, and Brenda Yeoh. Singapore: A Developmental City State. England: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1997. Powell, Robert. Living Legacy: Singapore's Architectural Heritage Renewed. Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society, 1994. Siong, Ng Poey, ed. Singapore: Facts and Pictures 1997. Singapore: Ministry of Information and Arts, 1997. "Conservation Homepage." http://www.ura.gov.sg "Float Your Boat: Quayside cuisine by the riverbank." http://www.happening.com.sg/food/feature "Singapore: River of Life."

Illustration Credits 1a. Powell, Living Legacy,

p. 50. |

10a. Interior of the Lim Shophouse showing original restored furniture and teak floor boards.

10b. Original

floors giving access to external balcony. 11. Overall view along the Boat Quay area.

12a and 12b. Bu Ye Tian Proposal for the Boat Quay area - elevation, perspective and artist's rendering of the interiors. |

|

|