The West End Now

Artifacts, Layers, Traces and Trends

“Although we Americans talk much about the rapidity with which we accept change, this does not apply to the rapidity of intellectual change, I’m afraid. Generation after generation, [we] stick to the same foolish ideas about slums and slum dwellers.” –Jane Jacobs

Introduction

Today’s West End is an extremely polarized environment, though the divide between the old and new structures has been building on the site for decades. As recorded in the previous assignment, the immense growth of Mass General Hospital and its associate institutions eroded away at the “stable, low rent” residential neighborhood established along Cambridge Street by the early 20th century (Jacobs, 272). These two layers would compete until urban renewal swept away the vast majority of the older development in the early 1960s. The few buildings that survived this clearance process were either valued as a landmark or served a purpose for the hospitals. These buildings are now artifacts of the original neighborhood, and the traces they contain tell the story of site’s past and indications for its future.

Discernible layers

Walking through the site, it is very clear which buildings make up the two layers based on a number of characteristics. Stemming from the post-renewal buildings’ implementation as part of a single master plan, they form a very cohesive layer. First of all, with only a few exceptions the buildings constructed since urban renewal are 40-year-old structures at a maximum, and thus share several basic architectural characteristics popular during this period of time, tying them together stylistically. Most include steel frames, strip windows, arcaded ground floors with setback entries, and glass and concrete as primary materials. In addition, healthcare buildings require consistent updating as technology and knowledge advances, meaning they are rebuilt at a faster rate than buildings with less specialized uses. For example, Shriner’s Hospital was first built on the site in 1967 and reconstructed entirely as recently as 1999. Similarly, Mass General’s most recent wing was just completed last year. This constant upgrading of hospital facilities, most notably the exterior shells, only exaggerates the discrepancy between old and new construction from the standpoint of visual cohesiveness.

Secondly, since the post-renewal buildings are generally healthcare institutions of various specializations, they all need to meet roughly comparable spatial requirements, which translates to a similar building scale. Even Charles River Plaza, designed to be the area’s major shopping center, contains nine floors of doctor’s offices above, including entire divisions of Mass General Hospital. Since healthcare facilities generally separate patients with different needs by locating them on different floors, their programming stacks vertically to achieve heights in this case of about eight to ten floors. This relatively uniform height is far greater than the Old West Church, which up until the renewal was the tallest structure on the site. The contrast would be far less distinctive between the old and new buildings if the new developments were, for example, low-lying warehouses rather than towering hospital facilities, despite the obvious differences in architectural style as mentioned earlier.

Clearly considered an eyesore compared to the new construction, Mass General constructed a wall to cap off remnants of old row houses along Cambridge Street to keep these buildings from appearing obsolete to patients entering its parking garage. The neighboring buildings were demolished recently to make room for the garage’s driveway, and these two buildings are slated for demolition in the next few years.

Because the post-renewal layer is so distinguishable in style and scale and also pervades across the majority of the site, any structure that does not conform to its qualities stands out conspicuously, as in the photo above. The dozen or so of these archaic structures make up the pre-renewal layer that was nearly eradicated entirely from the site in the early 1960s. They are all of masonry construction, mostly from brick, and often built on the site as of 1900. These buildings are united by their clear signs of deterioration and wear over the last century.

The only instance where these two distinctive layers merge is the Mass General complex that seems to self-regulate the integration of its old and new structures. Otherwise, the pre-renewal remnants are being pushed out by or under the post-renewal layer, in some cases very literally as in the example shown in the previous photo. The general attitude planning-wise towards these older buildings falls into the following two categories: celebrated artifacts or placeholders. Besides being keys to the past as artifacts themselves, both types of artifacts carry traces of the history of the site. Because so much of the pre-renewal layer was razed, paved, or rebuilt so deliberately in the 1960s, the layers, artifacts and traces on the site are highly intertwined.

Celebrated Artifacts

There are three key examples of artifacts celebrated as landmarks of the old West End. Saved from urban renewal because of historical significance, the Old West Church and the Harrison Grey Otis House have been considered landmarks since 1935 and 1950 respectively. They are both dutifully demarcated with plaques, which declare their historical importance. The third iconic artifact, The Charles Street Jail, did not become celebrated until as recently as 2007 when it was converted for use as a hotel.

Of these three buildings, only the church still fulfills its original purpose, though its usage has not been constant over the years. It was founded as a Congregational Church in 1737, built of wood, and rebuilt in stone in 1806 after the British burned the wooden building down during the American Revolution. The building was retired as a church by 1894, a sign that the majority of upper class residents of that time abandoned the area as it became less fashionable. The structure served a brief stint as a branch of the Boston Public Library before reopening in 1964 as a Methodist church for the new, working-class West End demographic. While the church’s usage records the changes in the area’s population, its grounds contain traces of the development of Cambridge Street from a single lane road to a major transportation route. While historical photos show the churchyard level with the street, it is now about five feet above the grade of Cambridge Street and contained by concrete bearing walls, as shown in the photo below. Clearly, when Cambridge Street was widened in the late 1920s, it cut into the slope of the church’s land and the perpendicular streets were adjusted with steeper slopes to accommodate the change in grade.

These concrete bearing walls have several large cracks, revealing decades worth of stress from holding back soil. Also note the carefully refinished brick sidewalks along Cambridge compared to the cracked perpendicular sidewalk.

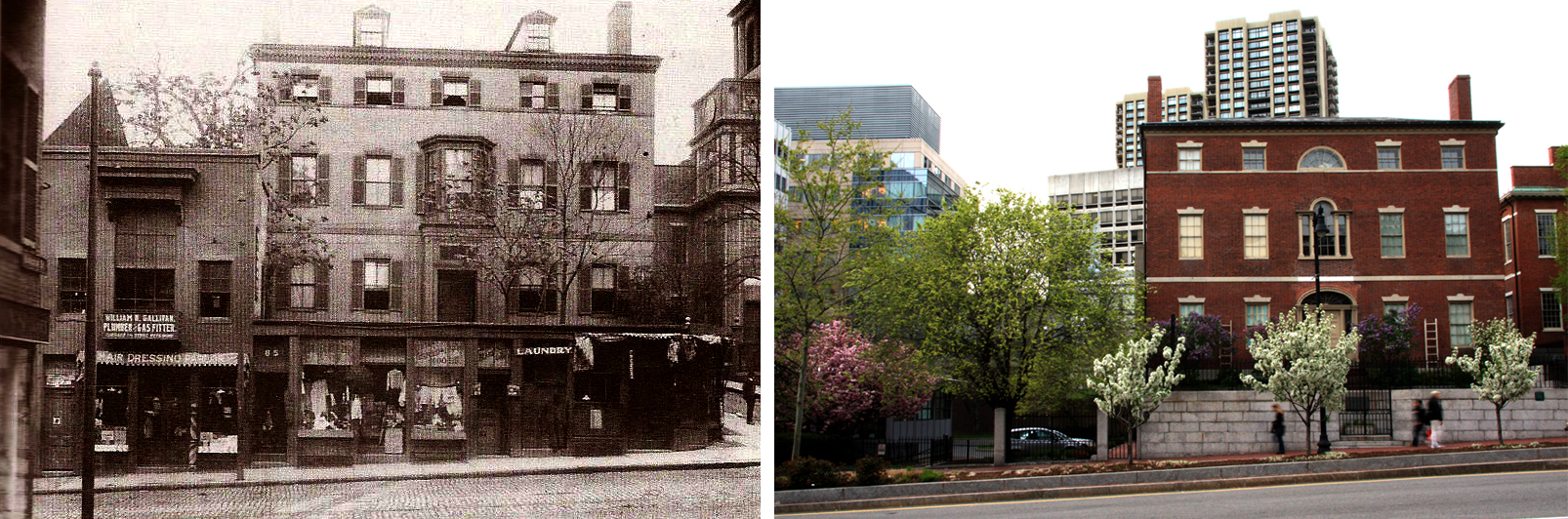

The Otis House and the Charles Street Jail, on the other hand, are maintained for purposes even further removed from their original use than the Congregational-turned-Methodist church. The Otis House was designed and built in 1795 by noted architect Charles Bulfinch as a wealthy, upper-class residence. Like the majority of the West End, it was converted from a single-family home for higher density use, in this case a boarding house with an addition for a Chinese laundry below. By the 1950s, it had been stripped back to its original conditions and restaged with the belongings of Harrison Grey Otis for conversion into a museum which still operates today to celebrate a selective history of the building’s more prestigious uses. Traces of the additions that were made during its use as a boarding house still remain, particularly the removal of a bay window and the new stone walls, as shown in the set of photos below.

The Charles Street Jail underwent a similar transformation towards upper-class ideals. The jail was built on the site in 1843, and actively detained Boston’s criminals up until the 1990s. It was progressive for its time, providing ventilation and natural light for the prisoners held there, but by 1973 it was found by law to be violating prisoners’ rights to adequate living conditions. Mass General bought up the property, and the condemned jail stood inoperable on the land for fifteen years until it was leased and redesigned as the posh Liberty Hotel. Not only was the original structure rehabilitated, the history of the jail was also rejuvenated as a unique selling point for the refined, luxury hotel despite the obvious clash with its harsh past. In fact, the 12 out of 300 rooms that were rebuilt within the walls of original cells are ironically the most expensive rooms in the entire hotel, boasting “floor to ceiling windows . . . which peer out through ornate ironwork” as advertised by the hotel website.

While there is no plaque in front of the building to observe the jail’s past, its history is certainly unforgettable while sitting in the hotel lobby’s two bars, named Clink and Alibi, pictured above. In some ways, this artifact is even more memorable than the touristy Otis Museum, because it’s operation has permeated into the area for day-to-day use by the locals.

Placeholders

The remaining artifacts on the site that are not considered celebrated artifacts are generally owned by Mass General or Mass Eye and Ear and for temporary usage. There is no indication of any care put into their upkeep over time, given the boarded windows, moss-covered brick, and peeling paint that mar many of the formerly elegant facades. As Jane Jacobs points out in The Death and Life of Great American Cities, cities need aged buildings because “there is no leeway for chancy trial, error and experimentation in the high-overhead economy of new construction. New ideas must use old buildings” (Jacobs, 188). These healthcare institutions use the mere presence of these old structures to ward away new investors from building on land they are eyeing for expansion. MGH in particular sits on the property with slight occupation of the structure until the hospital is certain that new construction on the site would be viable for its growing needs. The previous uses of the structures vary from institutional buildings, such as the Winchell Elementary School, to old residential structures and are only identifiable as Mass General property through extensive signage. Key examples of these buildings include a freestanding row house at 25 North Anderson Street, and two mixed-use buildings at 313 and 315 Cambridge Street.

Notice the detailed entryway and window cornices as well as the ripped out ground floor in favor of a storefront from the building’s former uses. The signage on its side identifies it as a MGH structure with the hospital’s colors.

The row house on North Anderson Street, shown above, is now satellite office space for Mass General. While the sign does not make a point to associate the structure with the hospital through the use of Mass General’s name or insignia, the colors and font selection are consistent with the rest of Mass General’s signage. The Federal style detailing around the doorway and windows indicates that this house was designed for a wealthy resident. However, the ground floor is also crudely ripped out and replaced by a more modern storefront, a vestige of the West End’s eventual conversion from single family housing to mixed-use, low-income apartments by the 1930s. The owner at the time likely wanted to maximize his profit on the building by leasing a portion of the ground floor for retail as rents dropped lower with each wave of immigration.

This photo above, taken from the back of the same row house, captures exactly how little interest MGH has in maintaining this building. It has been clumsily retrofitted with what looks like an air conditioner protruding right through a boarded up window for the office workers, though their access to natural light is clearly not a priority. The entire block it sits on is used primarily as a parking lot, so the former streets were paved over with no concern for the existing sidewalk. It has been paved into the ground for the sake of additional parking spaces. The one green chair is used by the security guards that rotate through the hospital’s campus, though it recalls the image of a mother who may have once sat in the same spot, watching her children play in the quiet alleyway behind her family’s apartment.

At least one of these alleyways is very well preserved on the site, formerly known as Cambridge St Avenue, which separated the old jail grounds from the residential block along Cambridge Street. 313 and 315 Cambridge Street, now an old apartment building with a ground floor travel agency and an unknown failed retail venture next door, have delineated the back alley since before urban renewal. While similar apartments once faced these artifacts on the other side of the alley, a wing of Mass General now maintains the alley’s boundary. The alley is for pedestrian use only.

One remaining street tree still grows along the former alley. Compared to the neatly turfed landscape that covers most of MGH’s campus, the presence of this tree startles the passerby. It has very few buds, compared to most other trees in the area that are starting to leaf, which is not surprising given that the tree can only receive early morning and late afternoon sun in such a tight alleyway, barely wide enough for a car to pass through. This alley covered more distance up until the last five to ten years when Mass General destroyed some adjacent buildings to make room for parking garage access, walling off these remnants as shown in an earlier image. Still, these placeholder artifacts, buildings, alley, and tree alike, together uphold a small but remarkably telling piece of the built environment typical of the pre-renewal layer.

Trends and Predictions

While conducting my field research for this paper, I had the great opportunity to speak with the owner of the small travel agency located at 313 Cambridge Street. When she saw me taking photos of her building, included above, she came outside to ask me to leave, thinking I was surveying the building for the hospital. She quickly apologized when she realized I was a student, after muttering, “Cameras make me nervous,” under her breath. She explained her reaction by telling me a heartbreaking story.

Until recently, a 70-year-old man named Joseph Christolli owned her building, and the locals in the area often referred to him as the last West Ender. He was born in the West End and lived on Minot Street until its destruction during urban renewal. Not wanting to leave the neighborhood that he loved, he moved into 313 Cambridge Street and eventually managed to buy the building, renting it as five apartments and living on the top floor himself. He lived there undisturbed until about a year ago when he began receiving lawyers representing Mass Eye and Ear, which had recently moved into the building next door. They offered to buy him out of his building in order to tear everything down and consolidate the lot for new construction. He refused adamantly, insisting that he was determined “to live and die a West Ender. But the lawyers never gave up,” the travel agent added, and eventually threatened Joseph with a lawsuit. While she doesn’t know many of the details that resulted in the settlement, he moved to Woburn “to be miserable” a few months ago, and she now pays her rent to Mass Eye and Ear.

This story sounds ominously similar to the accounts of West Enders forced to relocate during urban renewal after the state gained ownership of the land through eminent domain. Though the renewal was largely and almost immediately regarded as one of the worst mistakes in American urban planning, somehow history is allowed to repeat itself concerning the few buildings that did survive and are now artifacts of the pre-renewal environment. For many of them, particularly the placeholder artifacts discussed earlier in this paper, it’s only a matter of time before the post-renewal layer wipes them out. As Jane Jacobs points out, “Although we Americans talk much about the rapidity with which we accept change, this does not apply to the rapidity of intellectual change, I’m afraid. Generation after generation, [we] stick to the same foolish ideas about slums and slum dwellers” (Jacobs, 285). This quote from Jane Jacobs about the shortcomings of intellectual change is hopefully one of the few cases in which she is ever mistaken. It is my hope that while it seems too late to prevent the inertia of this trend of destruction from playing out in its entirety in the West End, the mistakes made there may at least save low income communities in the future.