It's Massachusetts; I Was Bound to Have a Liberal Yuppie Moment at Some Point, Right?

by Carlos Greaves

Dear Dad,

It feels unnatural writing you a letter, knowing that you are thousands of miles away, when the only time I spent away from home during the first eighteen years of my life was for a week at Grandma's house. Life here at MIT is amazing, and I am so thankful it has not snowed again, yet. Still, I can't wait to see you guys for Thanksgiving, and see Texas again. Sometimes I find it hard to believe that I am already in college and away from home.

I've already told you this, but it was a bit of a shock for me when I first arrived here in Boston. I had to adjust to doing everything on my own, which was especially unpleasant when I got sick. I never expected to spend so much of my time doing basic chores like grocery shopping, cooking, and laundry. I never really appreciated the amount of work Mom did for us back home. I can't believe I used to complain about trivial things like taking out the trash and doing the dishes. I guess that's part of the wisdom I've gained since coming to MIT, realizing just how much you and Mom helped me back home. I will never be able to thank you enough for that.

The most challenging thing I have had to deal with on my own is food. I seriously took for granted being able to go to our refrigerator at home and eat whatever I wanted. At MIT, I have either had to make time to go grocery shopping, or pay ridiculous prices for meals at the food courts. Thankfully, I have found a community both in my dorm, and in my fraternity, where we often cook for each other and share groceries. I now see what a big job it was for Mom to buy groceries every week. I can hardly find the time to go to the grocery store myself. I can't imagine how time-consuming it must be for her to buy food and cook for the entire family.

By the way, I am really enjoying my Food For Thought class. Since I am responsible for and in charge of my own food now, the things we are learning in class could not possibly have come at a better time. The main book we are reading, called In Defense of Food, is particularly fascinating, because it defines food in a way I'd never thought about before.

...many of these industrially-produced “foods” are so processed beyond their original natural forms that they can hardly be considered food.

The author, Michael Pollan, considers most of the edible items we buy at the grocery store to be “food-like substances.” What he means is that many of these industrially-produced “foods” are so processed beyond their original natural forms that they can hardly be considered food. Pollan gives the example of yogurt, which is supposed to be a simple food derived from cow's milk. The problem with many yogurt products found in stores today, according to Pollan, is that they contain ingredients like high-fructose corn syrup, which has absolutely no nutritional benefit, and “natural” flavors, which, according to one of our classmates, is an umbrella term for just about any chemical that companies feel like adding to a product in order to enhance flavor.

The major problems with these “industrialized” foods, according to Pollan, are the negative health consequences associated with them. Pollan cites several studies that show that cultures that eat unprocessed foods, regardless of their supposed nutritional content, have significantly lower rates of heart disease and diabetes, conditions that are widespread in Western industrialized countries like the U.S. However, when non-industrialized cultures switch to a diet of industrialized foods, they quickly begin to develop these same health problems. Something about the Western diet, or arguably the advanced industrial lifestyle as a whole, is responsible for the many health problems in our society, and according to Pollan, that something has a lot to do with eating processed foods.

Pollan's book discusses a study that illustrates this idea; it was conducted in the 1980s with ten Aborigines in Australia. A researcher analyzed the overall health of a group of Aborigines who were living a “Western” lifestyle, meaning they were primarily eating processed, industrially-produced foods and leading sedentary lives. Many showed early signs of diabetes, were overweight, and had other health problems. The researcher then persuaded the group to revert back to the lifestyle of the previous generation, who had hunted for their own food and lived in the bush. Once the group of Aborigines returned to eating food caught or gathered in the wild and spent time and effort preparing it, they had significant increases in overall health such as lower blood pressure and healthier weight. This improvement in health was attributed to the lack of processed foods in their diet.

Their diet consists primarily of meat, milk, and blood; most nutritionists would call this a recipe for dietary disaster. This culture, however, seems to have none of the problems associated with heart disease that would be expected if a Westerner were to eat this diet.

One might think that the Aborigines' health improved because they started eating foods in the wild that happened to be high in vitamins and low in saturated fat. However, Pollan argues that the issue of diet cannot be simply broken down into a list of essential vitamins and nutrients. He states that food is a much more complex entity, and that nutritional science will never be able to pinpoint what constitutes a healthy diet. For example, Pollan mentions the Masai tribe in Africa. Their diet consists primarily of meat, milk, and blood; most nutritionists would call this a recipe for dietary disaster. This culture, however, seems to have none of the problems associated with heart disease that would be expected if a Westerner were to eat this diet. According to Pollan, this can only mean that there is something about the foods we eat, in addition to their basic nutritional content, that is causing major health problems in the U.S.

One aspect of the Western diet that Pollan associates with the increasing prevalence of diseases such as diabetes and hypertension is the fact our diet is much less diverse than it was just fifty years ago. Nowadays, according to Pollan, two thirds of our calories come from four crops: wheat, soy, rice, and corn. This is because these crops are among the most energy-dense, so it makes economic sense to rely on them for sustenance. Furthermore, the U.S. government subsidizes corn and soy farms, making them even more economical. However, according to Pollan, most of foods we eat contain highly refined versions of these grains that lack almost all of their original nutritional content.

Another problem with the American food industry is the limited range of nutrition in mass-produced foods due to their lack of diversity and quality. Both fruits and vegetables are stripped of much of their nutritional value due to the way they are currently grown and transported. Pollan describes a vicious cycle: to lower costs, farms simplify the foods they produce, often only growing the most economical variety of a certain species. They then grow as much of the same plant as possible, year after year, which means they have to add fertilizers and pesticides to keep the soil and plants healthy. This depletes the soil, which prevents the crops from absorbing the same amount of nutrients. For example, Pollan states that we would have to eat three apples today to get the same iron content of one apple grown in the 1940s.

In the meat industry, there is a similar depletion of quality and diversity. According to Pollan, ninety-nine percent of the turkey we eat comes from the exact same variety. Furthermore, most livestock, whether poultry or red meat, is raised in massive lots where animals are tightly packed and have to be pumped with antibiotics to prevent disease from spreading. The animals are also fed cheap, unhealthy grains, which just as in the case of fruits and vegetables, has lead to a decline in the quality of the meat we eat.

Yet another problem with the American food industry is the fact that we ship our food longer and longer distances between the farm and the supermarket. As a result, the industry has had to find ways to prevent food from spoiling before it is sold. According to Pollan, part of the reason the quality of the food we eat has gone down is because there has been a benefit for producers: foods with low nutritional content, or foods that are highly processed, can be stored for longer periods of time without spoiling. While it is comforting to know that many of the products we buy in the store will not spoil easily, it is scary to think that not even bacteria want to eat the stuff we buy.

While Pollan paints a pretty grim picture of our overall nutritional status, he does offer some personal recommendations to help us eat a better diet. For example, Pollan suggests that we eat the traditional foods of cultures around the world, whether it's the Greek diet or Japanese cuisine. According to Pollan, because these cultures have survived for thousands of years, they must have adopted healthy diets that allowed them to thrive. Additionally, these traditional cuisines lack the processed foods of the Western diet.

Pollan also refers to the suggestions of another writer, Wendell Berry, whose article, “The Pleasures of Eating,” we read in Food for Thought class. Berry's suggestions include participating in food production as much as possible, including growing, preparing, and cooking it. He also suggests that we learn the origins of the food we buy, and try to deal directly with the farmers who grow the food. Berry argues that adopting these practices not only results in a healthier diet, but also results in a more satisfying overall gastronomical experience.

I've been trained to take anything I read with a grain of salt, no pun intended. While Pollan's book, and even some of Wendell Berry's suggestions, have opened my eyes to the idea that the ideal diet is not one rich in certain vitamins but simply one that our ancestors would recognize, I am not convinced by all of the ideas Pollan presents. His book has certainly made me aware of how the American food industry falls short, and has shown me simple ways I can eat better food. Still, I don't think industrial foods are necessarily the enemy. For example, Pollan neglects to mention the fact that most cultures get significantly more exercise than Westerners, and I have always seen exercise as the most important contribution to my overall health. I have never personally seen more drastic changes in someone's health than when they have gone from exercising to not exercising. For this reason, I want you to read Pollan's book, because I'd like the opinion of someone with a more critical eye and a few more years of experience to determine whether or not Pollan's ideas really are the answer to the complicated health question.

Despite my doubts, I will end this letter with the following story. Halloween morning, I decided to try a grocery store called Trader Joe's, which I heard was easier to get to from my dorm than Shaw's. As I was biking down Memorial Drive, I passed by a parking lot where a bunch of people had set up tents and were selling food. I decided to stop by and check it out. I came to discover that it was a local farmer's market, and I went up and started talking to the vendors. I approached a woman selling apples and picked some up to inspect them. “Where were these apples grown?” I asked her, to which she answered simply, “On a small farm in Western Massachusetts.” I then bought a bunch of apples and went on my way.

What seemed like a simple question (“Where were these apples grown?”) still lingers in my mind. For the first time in my life, I actually purchased food whose exact origins I knew.

What seemed like a simple question (“Where were these apples grown?”) still lingers in my mind. For the first time in my life, I actually purchased food whose exact origins I knew. I now understood the “yuppie” mentality of eating nothing but local, organic foods. In a liberal city like Austin I had met plenty of people with this mentality, but it was not until I came up to Boston and started living on my own that I realized the appeal of such an attitude. There was something special about having a personal connection with the food I was about to eat. Then I thought, “Doesn't that make perfect sense? Shouldn't I know exactly where the food I eat comes from?” When I got home that morning, I did not throw away all the food I had sitting in my room just because it had more than three ingredients listed on the package. However, I am now thinking a lot more about buying local foods, and staying away from anything that doesn't expire until five months from now. I really want to know what you think about this book, and maybe we'll talk about it over Thanksgiving turkey, even if it comes from the same variety as ninety-nine percent of the other turkeys in America. I love you very much, and can't wait to see you, Mom, Alex, and Sara.

Your son,

Carlos

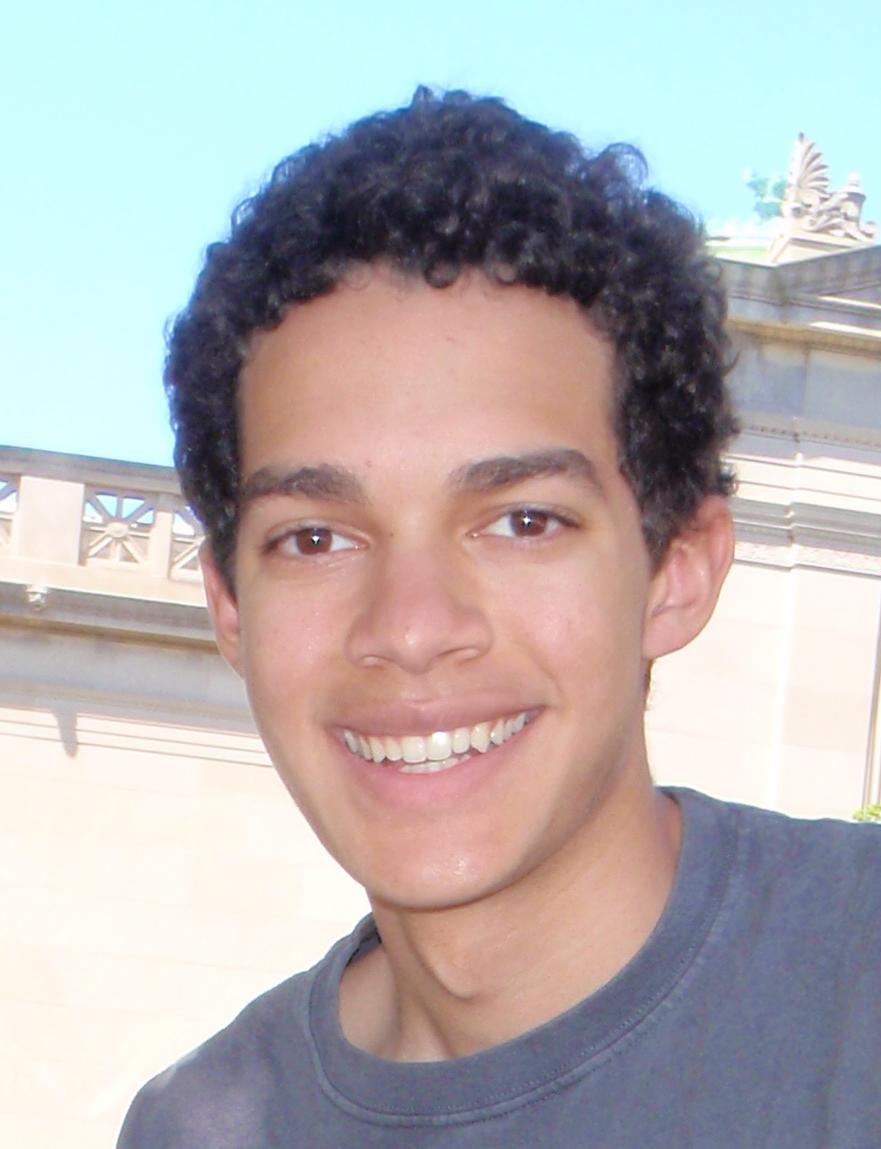

Carlos Greaves, from Austin, Texas, is a member of the MIT class of 2013. While he has not yet declared a major, he is strongly leaning towards Electrical Engineering, with a minor in Energy Studies. Carlos enjoys playing soccer, basketball, and the cello. He is also an architecture buff, loves Mexican food, and listens to indie rock. His inspiration for his essay/letter stemmed from the many discussions he had with his dad about diet and nutrition back in high school. His dad had advised him that as he went to college and started to take more responsibility for his own life, he should make exercise and diet top priorities. After reading Michael Pollan 's book In Defense of Food: An Eater's Manifesto, Carlos wanted to share Pollan's ideas with his dad, and perhaps this time, be the one giving the advice. In addition to thanking his dad for his source of inspiration for this piece, he would like to thank his freshman writing instructor, Dr. Karen Boiko, for helping him find a voice in his writing and for encouraging him to submit his work to this magazine.

Carlos Greaves, from Austin, Texas, is a member of the MIT class of 2013. While he has not yet declared a major, he is strongly leaning towards Electrical Engineering, with a minor in Energy Studies. Carlos enjoys playing soccer, basketball, and the cello. He is also an architecture buff, loves Mexican food, and listens to indie rock. His inspiration for his essay/letter stemmed from the many discussions he had with his dad about diet and nutrition back in high school. His dad had advised him that as he went to college and started to take more responsibility for his own life, he should make exercise and diet top priorities. After reading Michael Pollan 's book In Defense of Food: An Eater's Manifesto, Carlos wanted to share Pollan's ideas with his dad, and perhaps this time, be the one giving the advice. In addition to thanking his dad for his source of inspiration for this piece, he would like to thank his freshman writing instructor, Dr. Karen Boiko, for helping him find a voice in his writing and for encouraging him to submit his work to this magazine.