Should Physician-Assisted Suicide Be Legal?

by Ho Yin Au

| I will neither give a deadly drug to anybody, not even if asked for it, nor will I make

a suggestion to this effect.

- Hippocratic Oath |

| ...And, you know, they never say, we have to stop organ transplants. We have to

stop saving premature babies. We have to let them die. Oh, no, for that, it's okay to

play God. It's only when it might ease somebody's suffering that, 'Oh, we can't play

God' comes out. - Craig Colby Ewert (1947-2006 ) |

"So I guess I'm ready for the medicine," announced Craig Ewert. With his wife by his side, Ewert, who suffered from amytrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), calmly sipped a clear liquid from a small cup. Nearby, a representative from Dignitas, a Swiss organization that advocates for the right to die, videotaped Craig's death as proof to the authorities that no foul play was involved. This scene, featured in the PBS Frontline documentary The Suicide Tourist (2007), is the subject of intense debate between advocates of the right to die and the right to life. Should patients suffering from terminal illnesses or debilitating conditions have the right to end their own lives? And is it ethical for physicians to assist them in doing so?

What is "physician-assisted suicide" (PAS)? In its simplest form, PAS involves two people: a terminally ill patient and a physician. According to Dr. Barry Rosenfeld, an associate professor of psychology at Fordham University, the physician provides "guidance and assistance, such as a prescription for a lethal medication, along with instructions on how to use this substance." The patient's role would be to carry out those instructions, thus making the act a suicide (Rosenfeld). PAS is considered a form of active euthanasia.

The issue of the right to die and physician-assisted suicide has long been debated, even back to ancient Greece,1 with "quality of death" being a central concern of its advocates.

In the modern era, interest in PAS has intensified. This is far from surprising since people in industrialized countries today live much longer on average than they did a hundred years ago. In addition, medical diagnoses and prognoses are more accurate, and advanced medical technologies can prolong the lives of terminally ill patients, sometimes sacrificing quality for quantity of years.

Currently there is intense debate about the practice of PAS, which has been legalized in some countries such as Switzerland and a few states within the U.S. We will examine different sides of the PAS debate in response to the following questions:

Are terminally-ill patients who request PAS sane?

Is it moral for a physician to assist in ending a life?

Could legalizing PAS lead to a "slippery slope" in which other "mercy killings" might be justified?

In the United States, the late nineteenth and early twentieth century witnessed growing public concern about end-of-life issues. Advances in medical technology allowed for more accurate diagnoses by physicians, thus providing patients a better view of whether they are likely to survive an illness. Another discovery, morphine, together with the invention of the hypodermic needle, allowed doctors, by the mid-nineteenth century, to help patients better manage their pain (The Role of Chemistry in History). People also quickly discovered that morphine could kill rapidly and painlessly when given in large doses. Thus the option of physician-assisted suicide entered the public consciousness, and people started to debate PAS on medical, ethical, moral, and legal grounds (Rosenfeld 19).

In the United States, Anna Hill, whose mother had terminal cancer, campaigned actively to legalize PAS in the early 1900s. Her efforts resulted in the introduction of a bill legalizing physician-assisted suicide in Ohio. However, heavy opposition from medical journals and the public media defeated the bill in 1905. The bill's defeat led to the demise of the PAS movement in the U.S. for much of the 20th century (Rosenfeld 20-21).

... interest in PAS was halted by World War II and the discovery of Aktion T4, Nazi Germany's euthanasia program that "included adults with chronic disabilities, incurable illnesses, and persons not of German descent."

Meanwhile, in Europe, there was a parallel awakening of interest in physician-assisted suicide. Social anthropologist Dr. Frances Norwood has outlined the progression of the PAS debate in Europe in her book The Maintenance of Life: Preventing Social Death Through Euthanasia Talk and End-of-Life Care-Lessons from the Netherlands (2009). In the 1930s there was renewed interest in legalizing the practice in Europe, but that interest in PAS was halted by World War II and the discovery of Aktion T4, Nazi Germany's euthanasia program that "included adults with chronic disabilities, incurable illnesses, and persons not of German descent. The T4 program was expanded under Hitler's regime and by 1941 was attributed with the deaths of an estimated 75,000 to 250,000 men, women, and children" (Norwood 80). Although Hitler suspended Aktion T4 in the early 1940s, it is widely regarded as the precursor to and training ground for the Nazi death camps in which millions of Jews and others deemed "socially unacceptable" (e.g., Gypsies, homosexuals, Jehovah's Witnesses, Communists) were killed (The History Place: Holocaust Timeline).

However, after the defeat of the Nazis in World War II, interest in PAS again strengthened in Europe. Several assisted suicide court cases in The Netherlands during the second half of the century began to set precedent on the conditions required for PAS, eventually leading to its legalization in that country in 2002 (Norwood,94). Since then, some American states and other countries have legalized PAS: Belgium, Switzerland, Luxembourg, and the U.S. states of Oregon, Washington, and Montana. A number of other American states have also tried to legalize the practice, but failed due to intense opposition from pro-life groups. Physician-assisted suicide is heavily regulated, however, in the countries and states where it is legal. Take a look at the Netherlands, for example. Chapter II, Article 2 of the Dutch Termination of Life on Request and Assisted Suicide (Review Procedures) Act of 2002 lists numerous requirements for the patient's physician and bestows upon him or her the role of gatekeeper:

1. The requirements of due care, referred to in Article 293 of the Penal Code mean that the physician:

a. holds the conviction that the request by the patient was voluntary and well-considered,b. holds the conviction that the patient's suffering was lasting and unbearable,

c. has informed the patient about the situation he was in and about his prospects

d. and the patient holds the conviction that there was no other reasonable solution for the situation he was in,

e. has consulted at least one other, independent physician who has seen the patient and has given his written opinion on the requirements of due care, referred to in parts a-d, and

f. has terminated a life or assisted in a suicide with due care.

Note that the process must be repeated with another physician (part e) before the patient's doctor can prescribe the medicine that will end the patient's life. The law also sets aside additional requirements for minors: parental approval for children aged twelve to sixteen and parental involvement in the process for teenagers aged sixteen to eighteen. If the patient is sixteen or older and incapable of expressing his will, but made a written request prior to this condition, the physician may carry out the request.

Beyond the law, a typical physician will make sure that the decision was discussed among the patient's family members; some doctors even attempt to involve estranged members (Norwood 166). They will also determine whether to move forward with the request, based on observations of the patient. Thus, if the physician feels the request for PAS was made under coercion or that the patient can't articulate consistently the rationale behind the decision, he/she may decide to halt or slow the process (Norwood 44-47).

However, are terminally ill patients who request physician-assisted suicide mentally incompetent? In the U.S., if a person expressed actively suicidal thoughts or had attempted suicide and failed, that person would usually be considered "mentally incompetent" (Mitchell 117). These patients are typically institutionalized in a secure ward of a psychiatric hospital and evaluated and closely monitored for a period lasting up to multiple weeks. They are usually released only when they are deemed no longer dangerous to themselves.

John B. Mitchell, professor of law at Seattle University School of Law, however, argues that terminally ill patients seeking PAS are not mentally incompetent. In his book Understanding Assisted Suicide (2007), he explores the notion of "competence" and uses the analogy of the flu to illustrate his point:

Did you ever have the flu-the four- or five-day, sick as a dog flu? Lying in bed, aching, half sleeping and half waking, drifting in and out of dreams, too weak to move, snatches of conversations and faces of caretakers briefly moving through your consciousness and then forgotten, and always a pervasive sense of being miserable. For the worst of those four or five days, you did not live in the same world as other people. The sick do not. And that's the flu. (Mitchell)

... just as a child may be competent at building Legos, but incompetent in driving a truck, a terminally-ill patient may be competent at making end-of-life decisions but incompetent "about the wisdom of committing to a complex real estate transaction."

Mitchell asks the reader to imagine dying from pancreatic cancer: the patient had probably taken a lot of "extremely strong medications, at extremely high doses, many of them painkilling narcotics." The resulting effect is a confused mind, and an endless cycle of pain-medicine-confusion that leads to depression. However, the patient is still capable of making rational decisions based on his/her current predicament. Mitchell argues that, "Such persons understand who they are, whose life it is, and whether they want it to go on." Lastly, he proposes that competence is relative to the matter at hand: just as a child may be competent at building Legos, but incompetent in driving a truck, a terminally-ill patient may be competent at making end-of-life decisions but incompetent "about the wisdom of committing to a complex real estate transaction" (Mitchell 117-119).

Mitchell's argument is reflected in the case of Craig Ewert, the subject of the documentary film The Suicide Tourist, whom we briefly encountered in the introduction. A retired professor, Ewert had decided to end his life after finding out he had amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), better known as Lou Gehrig's Disease. ALS is a progressive, severely debilitating neurological disease with no known cure; the later stages of the disease involve complete paralysis. The film portrayed Ewert as a rational individual who was mentally competent and determined to see his request for PAS carried out to the end, even if it meant traveling to Zurich, Switzerland where the practice is legal. He was not depressed or insane. In fact, he was not tired of living, just tired of ALS. Ewert stated: "I'm not tired of living. I'm tired of the disease, but I'm not tired of living. And I still enjoy it enough that I'd like. . . I'd like to continue, but the thing is that I really can't" (The Suicide Tourist).

However, opponents of PAS hold fast to the notion that anyone who attempts or desires suicide is mentally incompetent. Countering Mitchell's line of reasoning, they argue that "a demoralized patient would be unable to think reliably about the remainder of her life, and therefore incompetent to decide to commit physician-assisted suicide" (Kissane 21). Many health care providers take this stance, as the refusal of care or expressing a desire to die-against the recommendations of professionals-is viewed as irrational behavior. Opponents also argue that requests for PAS are a "call for help by patients who are not receiving sufficient symptom relief (whether the symptoms are physical, such as pain, or psychiatric, such as depression) rather than a 'rational' request," essentially a signal for healthcare providers that the patient needs more palliative care (Rosenfeld 10).

Is it immoral for a physician to assist in ending a patient's life? Opponents argue "yes"-when physicians graduate medical school, they take an oath. In many cases that promise is the Hippocratic Oath, part of which states "I will not give a lethal drug to anyone if I am asked, nor will I advise such a plan." Recall that PAS involves a lethal prescription and instructions on how to consume the medication---a clear violation of the oath, thus an immoral and unethical act by the physician.

"If [PAS is] legalized, the fear is that the doctors' traditional role as healers is confused-patients will ask, 'are they here to heal me or kill me?"'

Unsurprisingly, there is also heavy opposition to PAS from some major religions. "If [PAS is] legalized, the fear is that the doctors' traditional role as healers is confused-patients will ask, 'Are they here to heal me or kill me?'" says Daniel Chan, Associate Pastor at the Boston Chinese Evangelical Church, in a recent interview. "Doctors may end life too early due to medical costs, wrong diagnosis, or to save work." The implication is that some doctors may decide to give preferential treatment to those who have a better chance at survival than those who are clearly about to die. However, Pastor Chan also drew a distinction between PAS and withdrawing life support from a comatose patient: "If the patient himself can't breathe, and his heart isn't beating on his own, then it is not euthanasia when the doctor withdraws life support...The patient is already dead, kept alive only by high-tech life sustaining equipment."

A new trend in the denial of life support is the recent practice of terminal sedation. It involves cases in which a terminally-ill patient is dying and experiencing unbearable pain that cannot be treated. A physician can sedate the patient while food and water are withheld. The patient eventually dies of starvation or dehydration (Mitchell 25). A patient may request that this be done in the last days of life to alleviate unbearable pain. While this practice can be considered euthanasia, it is differentiated from PAS by its passive nature, and is increasingly accepted by medical professionals as a middle ground.

Moreover, those arguing the merits of the Hippocratic Oath will be dismayed to learn that the Hippocratic Oath taken by doctors in modern times (see Appendix) is a different version. It does not say anything about lethal drugs or physician-assisted suicide. It does, however, mention "But it may also be within my power to take a life; this awesome responsibility must be faced with great humbleness and awareness of my own frailty. Above all, I must not play at God." In physician-assisted suicide, since it is the patient who "plays God" by making the decision to end a life, doctors practicing PAS are not immoral, at least in terms of oaths. Religious opponents of PAS, however, such as the Catholic Church, claim that it is wrong for a physician to "play God," killing others at their mercy. "Only God can take life away. The Bible tells us not to kill. Suicide is a person killing himself. Physician-assisted suicide is a person killing himself," Pastor Chan said when asked about the religious aspects of PAS. "Our view is that life is sacred. It shouldn't be taken away lightly; PAS is a scary procedure that is irreversible."

... advocates of legalizing PAS contend that physicians "play God" regularly when they resuscitate a patient, transplant an organ, or save a premature baby-why should an exception be made in this case...

However, advocates of legalizing PAS contend that physicians "play God" regularly when they resuscitate a patient, transplant an organ, or save a premature baby-why should an exception be made in this case (The Suicide Tourist)? It may be because the above procedures involve saving lives, while PAS deals with ending lives. In countries where physician-assisted suicide is legal, doctors are not required to perform the procedure if it conflicts with their personal religious or moral beliefs (Norwood).

Lastly, opponents argue that legalizing PAS could lead to a "slippery slope;" the bottom of this slope is the "involuntary killing of the most vulnerable in society (the elderly, sick, disabled, or disadvantaged minorities)" (Mitchell 60). They fear that physicians will transition from their traditional roles as healers to murderers, and that some patients will have their deaths hastened involuntarily (Norwood 86). Opponents of PAS have history on their side: Nazi Germany slid to the bottom of that slope when it instituted the eugenics program. Under that program, German physicians killed millions of people who they deemed "imperfect," a term they expanded to cover racial and social "deviants."

To guard against abuse of physician-assisted suicide and a potential "slippery slope,"proponents support stringent legal requirements for PAS, such as obtaining the opinions of two doctors and limiting the scope of PAS to only the terminally ill. Since we live in a democratic society, vastly different from a dictatorship, legislators can always amend laws to prevent fraud, close loopholes, or tighten requirements. Since PAS is an extremely sensitive topic, even the slightest sense of a problem could effect a change in the laws. Finally, because of the heinous crimes of Nazi Germany, proponents claim that physicians will never again slide downward morally as far as their German counterparts (Norwood). PAS has been around since ancient times, and interest in legalizing the practice increased in recent times. The movement has been successful in some jurisdictions, but has had its equal share of failures as well. What emerged from the movement were many arguments presented by both sides.

Are terminally ill patients who request physician-assisted suicide sane? Opponents do not differentiate PAS from other forms of suicide and view the decision for PAS as an irrational one. Proponents say that illness only affects how patients prioritize their competencies, that in the end they dedicate their remaining energies to things that matter to them most-in this case, their ultimate end-of-life decisions.

Is it moral for a physician to assist in ending a life? Opponents view PAS as unethical because it confuses the role of the doctor as a healer with a killer. They also view it as immoral because it's considered murder. Supporters argue that legal restrictions would limit the confusion, and doctors are not forced to practice PAS if it conflicts with their own moral code.

Would legalizing PAS lead to a "slippery slope?" Opponents fear that legalizing PAS could lead to involuntary termination of some patients' lives based on factors such as genealogy and handicapping conditions. In contrast, advocates contend that in places where physician-assisted suicide is legal, a structure is in place to regulate the practice. As it is a contentious issue, lawmakers will move to close any loopholes. Lastly, they say we will never go that far down the slippery slope because the atrocities of Germany in World War II are still fresh in many people's minds.

PAS is still a contentious issue today, legal in only three American states and a handful of European countries. Many people fear that it will lead to unintended killings, or worse, a second holocaust, while some doctors prefer their role as healers than "suicide assistants." Pain, lack of autonomy, and compassion will continue to motivate proponents to seek a practical solution, and turn patients choosing PAS into "suicide tourists." As the population ages, the debate about PAS will only intensify.

"Are you ready to activate the timer?" Arthur Bernard asks.

"I'm ready to activate," Craig responds.

"Mr. Ewert, if you drink this, you are going to die." . . .

Craig sips the medicine with apple juice, as Beethoven is played on a CD player in the room. A few minutes later he loses consciousness.

Mary Ewert hovers over Craig. "Safe journey. Have a good sleep."

1. The question of the right to die has a long contested history, dating at least back to the ancient Greeks, many of whom viewed the practice as ethical. Some advocates of PAS invoke the ancient Greek concept of "eudaimonia," or happiness across one's lifespan. This view held that one could not be happy throughout life if "one's death is preceded by a period of unbearable pain or suffering that one cannot avoid without assistance in ending one's life" (Shaw). Those who oppose PAS also often turn to ancient Greece and the writings of physician Hippocrates who stressed the utmost importance of patient well-being and the role of the physician as healer.

_______________________________________________

Appendix A: The Hippocratic Oath: Modern Version

I swear to fulfill, to the best of my ability and judgment, this covenant: I will respect the hard-won scientific gains of those physicians in whose steps I walk, and gladly share such knowledge as is mine with those who are to follow. I will apply, for the benefit of the sick, all measures [that] are required, avoiding those twin traps of overtreatment [sic] and therapeutic nihilism. I will remember that there is art to medicine as well as science, and that warmth, sympathy, and understanding may outweigh the surgeon's knife or the chemist's drug. I will not be ashamed to say "I know not," nor will I fail to call in my colleagues when the skills of another are needed for a patient's recovery. I will respect the privacy of my patients, for their problems are not disclosed to me that the world may know. Most especially must I tread with care in matters of life and death. If it is given me to save a life, all thanks. But it may also be within my power to take a life; this awesome responsibility must be faced with great humbleness and awareness of my own frailty. Above all, I must not play at God. I will remember that I do not treat a fever chart, a cancerous growth, but a sick human being, whose illness may affect the person's family and economic stability. My responsibility includes these related problems, if I am to care adequately for the sick. I will prevent disease whenever I can, for prevention is preferable to cure. I will remember that I remain a member of society, with special obligations to all my fellow human beings, those sound of mind and body as well as the infirm. If I do not violate this oath, may I enjoy life and art, respected while I live and remembered with affection thereafter. May I always act so as to preserve the finest traditions of my calling and may I long experience the joy of healing those who seek my help.

Source: <http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/doctors/oath_modern.html>

_______________________________________________

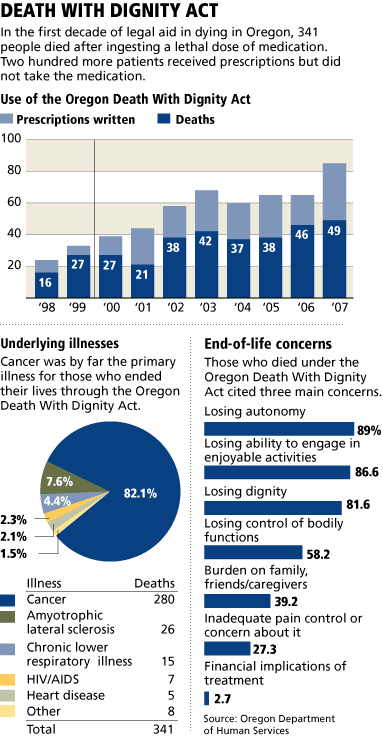

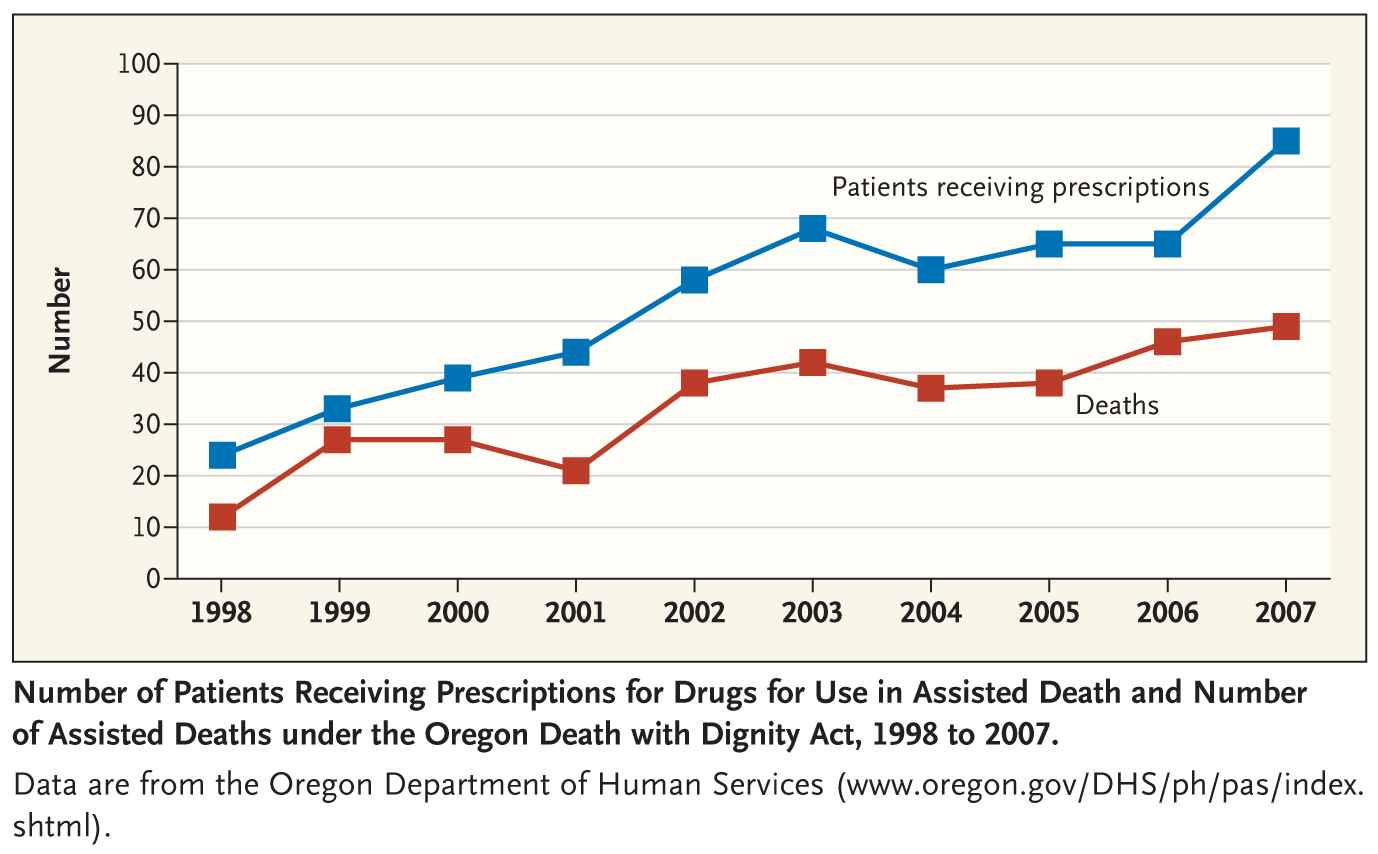

Appendix B: Charts and Graphs

Bibliography

Annas, George. "'Culture of Life' Politics at the Bedside-The case of Terri Schiavo." The New England Journal of Medicine. 352 (2005): 1710-1715.

Avitan, Galit, and Wimbush, Nick. "Gonzales v. Oregon (formerly Oregon v. Ashcroft) (04-623)." Cornell University Law School: Legal Information Institute Supreme Court Bulletin. 5 October 2005. Web. 6 March 2010.

<http://topics.law.cornell.edu/supct/cert/04-623>.

Ball, Deborah, and Mengewein, Julia. "Assisted-Suicide Pioneer Stirs a Legal Backlash." The Wall Street Journal. 6 February 2010. 26 February 2010 <http://online.wsj.com/article/ SB10001424052748703414504575001363599545120.html>.

Bergner, Daniel. "Death in the Family." The Times Magazine. 2 December 2007. Web. 6 March 2010.

<http://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/02/magazine/02suicide-t.html>.

Burns, et. al. Catechism of the Catholic Church. New York: Continuum, 2000.

Coughlan, Geraldine. "Dutch 'suicide consultant' jailed." BBC News 8 December 2005. 26 February 2010.

<http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/4509582.stm>.

Dahl, E. and Levy, N.. "The Case for Physician Assisted Suicide: How Can It Possibly Be Proven?" Journal of Medical Ethics. 32 (2006): 335-338.

"Death with Dignity Act Annual Reports." Oregon State Web Site. 3 March 2010. Web. 3 March 2010.

<http://www.oregon.gov/DHS/ph/pas/ar-index.shtml>.

Doyle, Len, and Doyal, Lesley. "Why active euthanasia and physician assisted suicide should be legalised." British Medical Journal. 323 (2001): 1079-1080.

"Dutch Legalize Euthanasia, The First Such National Law" The New York Times 1 April 2002: A5. New York Times on the Web.

<2002/04/01/world/dutch-legalize-euthanasia-the-first-such-national-law.html>.

Dworkin, Ronald, et al. "Assisted Suicide: The Philosophers' Brief." The New York Review of Books. 27 March 1997: Research Library Core, ProQuest. Web. 6 March 2010.

Emanuel, Ezekiel, and Battin, Margaret. "What are the Potential Cost Savings from Legalizing Physician-Assisted Suicide?" The New England Journal of Medicine 339 (1998): 167-172.

Emanuel, Ezekiel. "What Is the Great Benefit of Legalizing Euthanasia or Physician-Assisted Suicide?" Ethics. 109 (1999): 629-642.

"Euthanasia." BBC Ethics Guide. Web. 5 March 2010.

<http://www.bbc.co.uk/ethics/euthanasia/>.

"Euthanasia and Assisted Suicide." International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. Ed. William A. Darity, Jr.. Vol. 3. 2nd ed. Detroit: Macmillan Reference usa, 2008. 26-29. Gale Virtual Reference Library . Gale. blc Massachusetts Institute of Tech. 2. 6 March 2010.

<http://go.galegroup.com/ps/start.do?p=GVRL&u=camb27002>.

"The fight for the right to die." CBC News. 9 February 2009. 26 February 2010.

<http://www.cbc. ca/canada/story/2009/02/09/f-assisted-suicide.html>.

"Euthanasia." New Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 5. 2nd ed. Detroit: Gale, 2003. 457-459. Gale Virtual Reference Library . Gale. blc Massachusetts Institute of Tech. 2. 6 March 2010

<http://go.galegroup.com/ps/start.do?p=GVRL&u=camb27002>.

Golden, Marilyn, and Zoanni, Tyler. "Killing us softly: the dangers of legalizing assisted suicide." Disability and Health Journal 3.1 (2010): 16-30.

Gonzales v. Oregon. No. 04-623. Supreme Ct. of the us. 17 January 2006.

"Interview: Ludwig Minelli." PBS: Frontline. 2 March 2010. Web. 6 March 2010.

<http://www.pbs. org/wgbh/pages/frontline/suicidetourist/etc/minelli.html>.

"Holocaust Timeline," The History Place

<http://www.historyplace.com/worldwar2/holocaust/timeline.html> 22 July 2010.

Jost, K. "Right to Die." CQ Researcher. 15 (2005): 421-444. CQ Researcher Online . 3 March 2010.

<http://library.cqpress.com/cqresearcher/cqresrre2005051300>.

Kissane, David. "The Contribution of Demoralization to End of Life Decisionmaking." Hastings Center Report. 34.4 (2004): 21-31.

Lasagna, Louis. "The Hippocratic Oath: Modern Version." NOVA . 2000. 7 April 2009. 18 March 2010.

<http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/doctors/oath_modern.html>

Lavi, Shai. "How dying became a 'life crisis'." Daedalus. 137.1 (2008): 57+. Literature Resource Center. Web. 3 March 2010.

<http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?&id=GALE%7CA175286834&v= 2.1&u=camb27002&it=r&p=LitRC&sw=w>.

Linder v. United States. No. 05-268. Supreme Ct. of the U.S. 13 April 1925.

Norwood, Frances. The Maintenance of Life: Preventing Social Death through Euthanasia Talk and End-of-Life Care-Lessons from The Netherlands. Durham: Carolina Academic Press, 2009.

Mitchell, John. Understanding Assisted Suicide: Nine Issues to Consider. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2007.

Quill, Timothy. "Terri Schiavo-A Tragedy Compounded." The New England Journal of Medicine. 352 (2005): 1630-1633.

"Right to Die." National Survey of State Laws. Ed. Richard A. Leither. 6th ed. Detroit: Gale, 2008. 631-697. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Gale. blc Massachusetts Institute of Tech. 2. 6 March 2010. <http://go.galegroup.com/ps/start.do?p=GVRL&u=camb27002>.

"Role of Chemistry in History; History Affects Morphine: The Hypodermic Needle",

<http://www.tech.dickinson.edu/chemistry/?p=798

Rosenfeld, Barry. Assisted Suicide and the Right to Die: The Interface of Social Science, Public Policy and Medical Ethics. Washington. D.C.: American Psychological Association, 2004.

Shaw, David. "Euthanasia and Eudaimonia." Journal of Medical Ethics. 35 (2009): 530-533.

Spencer, Clare. "Daily View: Assisted suicide law clarified." BBC News. 26 February 2010. 26 February 2010.

<http://www.bbc.co.uk/blogs/seealso/2010/02/daily_view_assisted_death_guid. html>.

Steinbock, B.. "The Case for Physician Assisted Suicide: Not (Yet) Proven." Journal of Medical Ethics. 31 (2005): 235-241.

Steinbrook, Robert. "Physician-Assisted Death-From Oregon to Washington State." The New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (2008): 2513-2515.

The Suicide Tourist. Dir. John Zaritsky. CTV Television Network, 2007.

"U.K. TV To Air Assisted Suicide Film." CBS News. 10 December 2008. 26 February 2010.

<http: //www.cbsnews.com/stories/2008/12/10/world/main4660591.shtml>.

Van Der Heide, Agnes, et al. "End-of-Life Practices in the Netherlands under the Euthanasia Act." The New England Journal of Medicine. 356 (2007): 1957-1965.

"Washington Death with Dignity Act Forms Received by Department of Health." Washington State Department of Health: Center for Health Statistics. 19 February 2010. Web. 6 March 2010.

<http://www.doh.wa.gov/dwda/formsreceived.htm>.

Weide, Marc. "'I'm going to die on Monday at 6.15pm.'" The Guardian: 23 August 2008. 26 February 2010.

<http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2008/aug/23/ euthanasia.cancer>.

Wolf, Susan. "Confronting Physician-Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia: My Father's Death." Hastings Center Report. 38.5 (2008): 23-26.

Young, Robert. Medically Assisted Death. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Ziegler, Stephen, and Jackson, Robert. "Who's Not Afraid of Proposal B? An Analysis of Exit-Poll Data from Michigan's Vote on Physician-Assisted Suicide." Politics and the Life Sciences. 23.1 (2004): 42-48. Social Science Module, ProQuest. Web. 6 March 2010.

Ho Yin Au grew up in Hong Kong and moved to Boston when he was nine. Readmitted to MIT in 2010 after a fourteen year absence from school, he is currently a sophomore majoring in Course 3 (Materials Science and Engineering). Ho Yin is enjoying a new perspective on life at MIT as an older student. An avid photographer and advocate of career-technical education, he is the director of the media crew at SkillsUSA Massachusetts and loves to travel in his free time.

Ho Yin Au grew up in Hong Kong and moved to Boston when he was nine. Readmitted to MIT in 2010 after a fourteen year absence from school, he is currently a sophomore majoring in Course 3 (Materials Science and Engineering). Ho Yin is enjoying a new perspective on life at MIT as an older student. An avid photographer and advocate of career-technical education, he is the director of the media crew at SkillsUSA Massachusetts and loves to travel in his free time.