Site Through Time

Copley Square has not always been the lively public square it is today. In fact, there hasn’t always been a park space there at all. This part of the filled-in Back Bay is well known to Boston locals as well as tourists for the venerable Trinity Church, Boston Public Library and as the location of the finish line of the Boston Marathon, all of which make Copley Square an exciting place to visit and study. Some of these attracting factors have greatly affected the evolution of the square over the years. Although a few key landmarks have sustained, the comparison of maps from various time periods reveals that the square that now features high end hotels and a public park was once highly valuable for its institutional and artistic identity. The transition from this dominantly institutional land use can be traced back to changes in transportation technologies, remodeling of the parkland space, suburbanization and community movements.

The Square

When I first visited Copley Square, I got the impression that the green park space had historically been the main focus, since it is a popular meeting place and city center and because Boston as a city is known for its commitment to parkland and urban beautification. However, Copley Square was actually introduced as an afterthought in the scheme of the city. The landscape architect Arthur Shurtleff had the idea to thread extra green spaces into Boston’s metropolitan areas in order to unite the city. The introduction of the public square was evidently not a part of the city’s original plan, although it did fit in with the “Emerald Necklace” idea that was characteristic of Frederich Law Olmstead’s vision for the city [2]. While searching for the layout of my site during the 19th century, I came across the surprising discovery that the Copley Square Park had actually been developed on for a time. In my Hopkins map dating back to 1873, I noticed that the extension of the main road of the site, Huntington Avenue, is crosscutting the area that makes up the public park. There are still paved remains of the road in the park, and Sanborn maps even indicate its presence past its truncation in 1966[5]. This observation indicates that Huntington Avenue and any development along it, such as MIT buildings, were the predecessors to the square, and at some point the street traffic must have been redirected to the surrounding streets when the diagonal was cut off. Huntington Avenue interrupts the square in street maps dating all the way to the 1962 Sanborn Utility Map. The square wouldn’t likely have the same atmosphere that it does today, if it were intersected by the busy road; it would be nearly impossible to see the park area and the square filled with people for public ceremonies and mulling with visitors for midday farmers markets.

Transportation Techonology

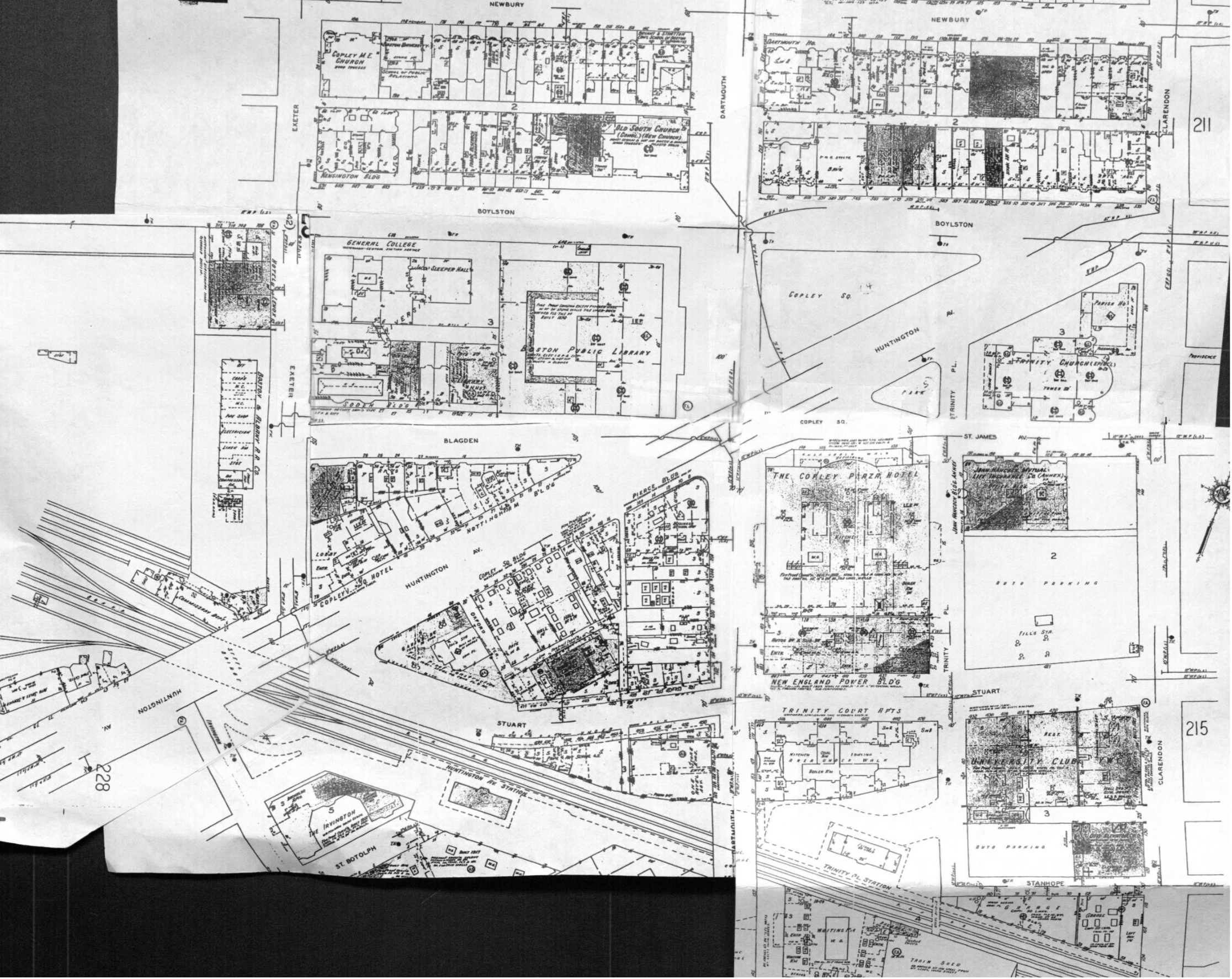

My site has always been bounded by major elements of Boston’s infrastructure, causing a clear divide between the sections of the blocks of the area that are friendly to pedestrians and the area south of Huntington Avenue that is more densely occupied with automobiles. Through the 1800s, the Boston and Albany railroad line is bordering the site and the railroad yard is indicated just next to it in the Hopkins maps from 1872 and 1888. With the need for an organized highway system for the city, the Massachusetts Turnpike was extended into my site as indicated in the Sanborn map of 1962. All the maps that I’ve collected have indications of railways and train stops just outside of my site’s boundaries: the Back Bay transit stop is located just outside of Copley Square and attracts a lot of traffic in Boston today. Huntington Avenue and the tunnel entrance to I-90 that sections off my site are characteristically busy roadways, which bring traffic to this area of the city. The railroad was undoubtedly very important to the early development of the square and the people who lived in it, as it offered goods, transportation and most importantly provided the greatest tool for the infill project that was the creation of the surrounding Back Bay in the late 1800s. On the Hopkins maps from 1873 and 1888, a significant amount of land, spaces and buildings is designated to the railroad system. I noted a few sheds and houses labeled for storage or maintenance of freight and cars as well as the large railroad yard stationed just outside my site. Now there are more parking lots and infrastructure elements of bridges and tunnels taking over these open spaces, representing the shift to modern transportation systems. The railroad is of course still relevant to the city’s needs; however, commuters and travelers have become increasingly dependent on automobile and subway travel now that both are accessible. According to Kenneth Jackson’s analysis of how the transportation revolution affected cities’ development throughout the years, Boston was known for its large proportion of suburban riders, compared to other communities [1]. Although automobile traffic was not a concern until the modern age, cars and railroad transit allowed this area to populate quickly and was a necessity in facilitating commuting as a more common practice. As a result of suburban growth and the commuter style of the city, this technology became particularly essential for people who wanted to live outside the city but needed to work within it. Evidence of this pattern is observed in the Sanborn utility maps of 1951 and onward. There are several storefronts and buildings labeled as “office space” along Boylston Street on the 1962 Sanborn utility map, which represents what the site looked like for the remainder of the 20th century. Parking garages and lots also appeared on my 1951 Sanborn map, taking up several sizeable plots of land and combining with other uses of land such as apartment or office buildings, both of which suggest an increased need for parking.

Suburbanization

By looking at earlier maps and distribution of building uses, it is evident that Copley Square was never an area dominated by single family residences; however, I did pick up the digression from small, single owner properties between as short a time period as 1875 to 1888. This was a time period during which multi-unit housing facilities became popular among the world’s greatest cities. According to Jackson’s discourse on upper-middle-class residences, in the last two decades before 1900, single family housing plummeted from thirteen-hundred to only 40 residences in New York City [3]. Although this could be considered an extreme case, Boston certainly has followed the same patterns as technology improved and styles adjusted. A difference in the divisions of the city buildings and properties around Copley Square is noticeable. For instance, there is the addition of the Harvard Medical College, the Boston Public Library and several large hotels in the 1902 Bromley atlas. These buildings replaced and condensed some unlabeled, open space from the Hopkins 1888 maps as well as some properties under single ownership. A trend that might have been responsible for this move away from residences and toward commercial use is the one of suburbanization. There are plenty of stores and offices that require working people and customers to stay running, nonetheless it seems that not many people are residing in the area around them. As a result of the movement of suburbanization and the expansion of Boston into some of the outlying rural areas, it was no longer necessary to be living in the same area that one was working in. Mass public transit and the introduction of the automobile also made this adjustment easy and preferable for many who wanted the access to the resources of the city but the quiet of a suburban home. The towns such as Brookline, Somerville and Cambridge, all on the route of Boston’s mass transit system, grew to notable counterparts to the city of Boston. The growth of Cambridge in particular can be correlated to some of the changes in my site since the institution once crowding the square, MIT, was relocated to this “suburban” outpost as it became more suitable for the diversifying university.

Landmarks and Institutions

The only significant landmarks indicated on my 1875 Hopkins map and still standing today are the two churches of the square. The Trinity church, beautifully constructed and naturally eye-catching is the focus of the square. The other church, situated across the street from Copley Square, as opposed to in the center of it, is the Old South Church. Although this area of Boston is not necessarily known for its religious significance, the people and the culture clearly do hold some value to religious tradition. The Trinity Church is an Episcopal church, which originates from the Church of England. It makes sense that this historical landmark would endure the years, since the people who owned land and settled in the Back Bay were originally of rich, British descent and there was probably a sizeable portion of them subscribing to this faith. Most of the names I observed on the 1872 Hopkins map seemed to reflect this demographic, some of the owners of properties around the area include Sumner, Symonds, Garfield and ‘HNF Marshall & WG Preston’. These buildings, along with the Boston Public Library and John Hancock tower, are the ones I would consider to have the most presence in the square. It is fascinating since the churches were built way back when the park area wasn’t even complete and before tall skyscrapers moved in, but the buildings still remain intact and in use today.

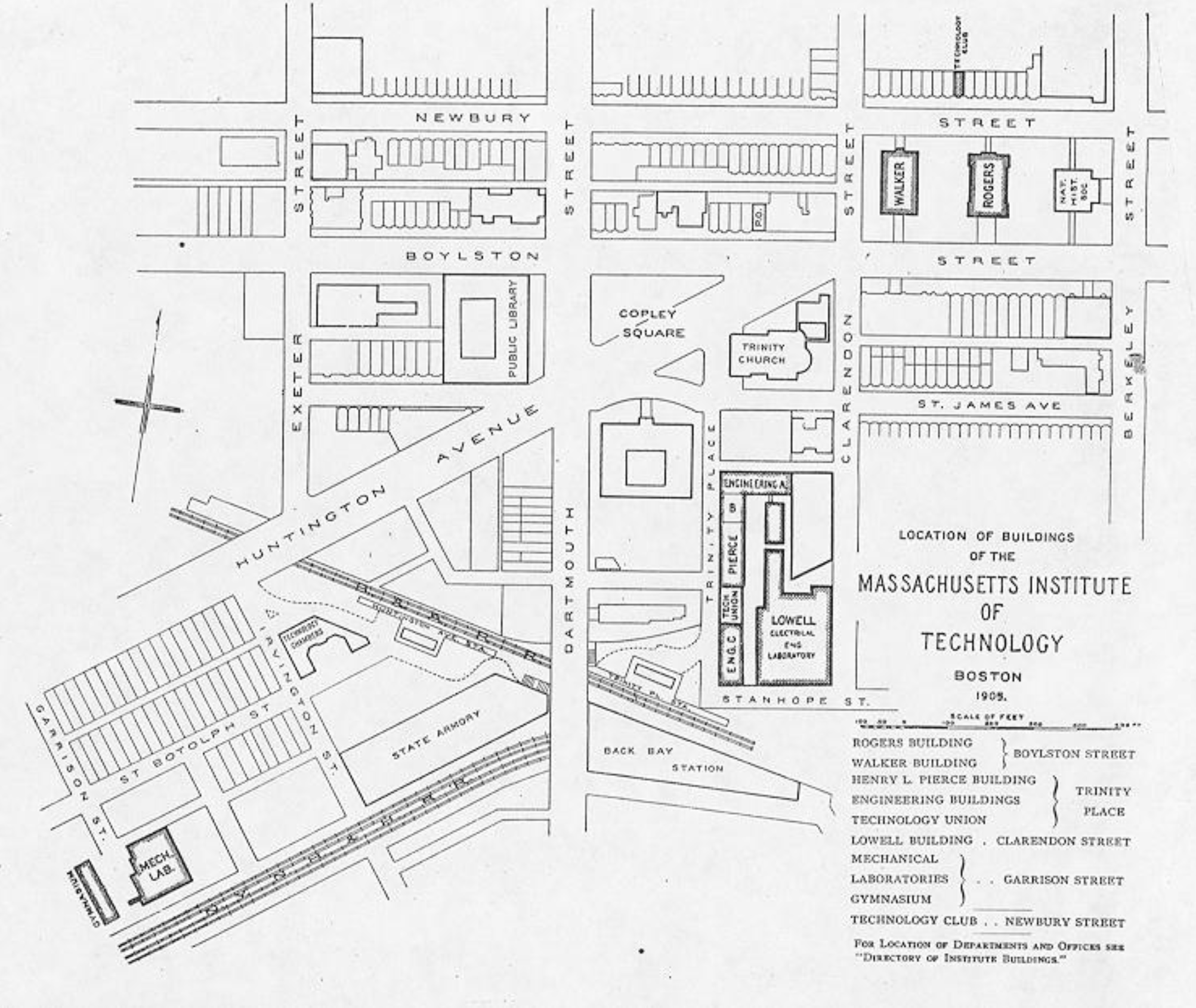

In addition to the institutional value of the historic churches that Copley Square holds, the Boston Public Library also functions as a center of knowledge and research open to all of Boston’s inhabitants. The library is clearly an anchor to the culture and usage of the square, since it was founded on Boylston in 1848, and has strengthened the square as a place for Boston residents, tourists, scholars and artists alike to enjoy [3]. There is evidence of its expansion from the 1951 Sanborn map, which actually had a Boston University building labeled behind it before the plot became part of the library. Boston today is rather populated with college aged students and young people, because of all the schools and industry it has to offer. While this trend may have taken a while to build up, Copley Square certainly got a head start on it. As mentioned earlier, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology buildings, labs and Gymnasium were once intertwined into the city blocks of this site. In addition to MIT, Harvard Medical College, The Institute of Fine Arts, Boston Art Club, Normal Art School and Prince School are all institutions that are present on the 1902 Bromley map of my site. According to Sam Bass Warner, the Industrial age was a critical time period for the development of Boston as a world class city. “A kind of merchant-shop-owner-craftsman coalition allowed the city to reach its peak” after the eve of industrialization [4]. The additions of international universities and important city projects during this era were certainly a cause of change to the area of Copley Square in particular. Copley seemed to have hit the jackpot with the Boston Public Library and the culture-rich institutes of all kinds. Particularly during the early 1900s, the site was celebrated for its institutional value. Prior to being dubbed Copley Square, the area was known as Art Square [5], not surprising considering the presence of Boston’s own Institute of Fine Art, along with a couple of other schools and an Art Club. The culture and upkeep of these institutions shaped the character and reputation of Copley Square, until it was named after the famous Bostonian artist John Singleton Copley.

The blocks around the square are crowded with high end hotels, to serve the square’s purpose as a huge tourist destination, and this isn’t just a recent development. Labeled in the 1888 Hopkins map is the Hotel Nottingham, wedged in between Blagden Street and Huntington Street. Although not the same one that stands there today, it is in the same interesting position with the entrance between two busy roads as the Westin now stands. This hotel wipes out a few singularly divided residences and replaces them with one large building. I would guess that although this is a fairly busy and wealthy area, it may not have been a very popular area for the rich Boston settlers to want to settle since it is right by the railroad yard and not too close to the Charles River shore. As a result of this along with the popularity of the area for businesses and tourism, there is a trend toward more hotels and commercial properties rather than permanent residences.

The John Hancock tower, along with some of the new development along the periphery of the square, is one of the last significant additions to the development and relevance of Copley Square today. This tower was constructed around the late 1970s and appears in the 1992 Sanborn map that makes it a modern visual contrast from most of the older style architecture and usage of the buildings around the square. The impressive skyscraper stands across the street from the Trinity Church and makes for an interesting collaboration between the eras. Since Boston is a historic city that has been becoming increasingly more modern and upscale, the juxtaposition of the John Hancock tower and the old Trinity Church truly epitomize the character of the city, which is evident in other notable sites across Boston, such as the financial district on State Street and the Fenway park area.

Conclusion

The use and development of Copley Square and my site at large will continue to change over time as the needs of Boston community also change. When the focus was on institutional development, Copley Square supported the burgeoning institutions. When railroads and transportation was being developed the area showed flexibility in its structure and roads. And when the future focus is found the area will find a way to accommodate the new focus.

Fig.1 G.W. Bromley Map of Copley Square, 1873-1875.

Fig.1 G.W. Bromley Map of Copley Square, 1873-1875.

Fig.2 G.W. Bromley Map of Copley Square, 1888.

Fig.2 G.W. Bromley Map of Copley Square, 1888.

Fig.3 Annotated map of site, 1902. Institutions colored in blue. Edited from 1902 Bromley.

Fig.3 Annotated map of site, 1902. Institutions colored in blue. Edited from 1902 Bromley.

Fig.4 Map of MIT's campus in the Back Bay. Photo courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.

Fig.4 Map of MIT's campus in the Back Bay. Photo courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.

Fig.5 Sanborn Utility Map 1950.

Fig.5 Sanborn Utility Map 1950.

Fig.6 Sanborn Utility Map 1962.

Fig.6 Sanborn Utility Map 1962.

Fig.7 Sanborn Utility Map 1992.

Fig.7 Sanborn Utility Map 1992.

References

[1] Kenneth Jackson. Crabgrass Frontier. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985. 36-37.

[2] Alex Krieger. Mapping Boston. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999. 216.

[3] The Boston Public Library. "BPL - History and Description." BPL - History and Description. http://www.bpl.org/general/history.htm

[4] Sam Bass Warner, Jr. Mapping Boston. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999.

[5] Jackie Yessian. "The Creation of Copley Square." Friends of Copley Square Copley Square Comments. http://friendsofcopleysquare.org/?page_id=178

Back to top

Fig.1 G.W. Bromley Map of Copley Square, 1873-1875.

Fig.1 G.W. Bromley Map of Copley Square, 1873-1875.

Fig.2 G.W. Bromley Map of Copley Square, 1888.

Fig.2 G.W. Bromley Map of Copley Square, 1888.

Fig.3 Annotated map of site, 1902. Institutions colored in blue. Edited from 1902 Bromley.

Fig.3 Annotated map of site, 1902. Institutions colored in blue. Edited from 1902 Bromley.

Fig.4 Map of MIT's campus in the Back Bay. Photo courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.

Fig.4 Map of MIT's campus in the Back Bay. Photo courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.

Fig.5 Sanborn Utility Map 1950.

Fig.5 Sanborn Utility Map 1950.

Fig.6 Sanborn Utility Map 1962.

Fig.6 Sanborn Utility Map 1962.

Fig.7 Sanborn Utility Map 1992.

Fig.7 Sanborn Utility Map 1992.