| The Emerging Mediascape | |||

|

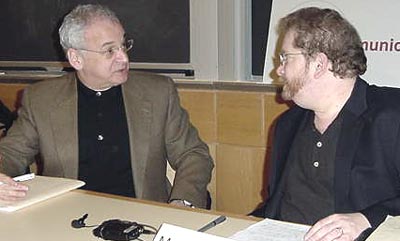

National Public Radio ombudsperson Jeffrey Dvorkin and Boston Globe media critic Mark Jurkowitz consider how new sources of information are interacting and competing with traditional forms of journalism. Are we less informed today, amid a torrent of voices and technologies offering us so-called news, than citizens in olden, pre-digital days? How has the role of print or radio journalism changed since the advent of the Web and the 24-7 operations of the TV cable news networks?

Jeffrey

Dvorkin is National Public Radio’s first ombudsperson,

a role in which he receives, investigates and responds to queries

from the public regarding editorial standards in programming.

Based in Washington D.C., he writes a weekly Internet column

for NPR Online at www.npr.org, and presents his views on journalistic

issues on-air on NPR programs. Before being named ombudsman

in February 2000, Dvorkin served as NPR’s vice president

for news and information. Previously, Dvorkin was a reporter

and managing editor for CBC Radio News and Information, a division

of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, where he was responsible

for all radio network newscasts. Mark

Jurkowitz is the media writer for The Boston Globe,

a position he has held since 1997 after spending two years as

the paper’s ombudsperson. Prior to that, he spent seven

years as media critic for The Boston Phoenix and author

of its “Don’t Quote Me” column. Jurkowitz began

his journalism career at the Tab Newspapers where he served

a two-year stint as editor. He spent a number of years as a

talk radio host, appearing on WRKO, WHDH and WBZ and is currently

a regular panelist on the weekly Beat the Press program

on Boston’s PBS outlet, WGBH-TV. Jurkowitz teaches media

ethics at Northeastern University and Tufts University. Webcast A webcast

of The Emerging Mediascape is now available. [This is an edited summary, not a verbatim transcript.]

MARK JURKOWITZ said the contest today between new and classic forms of media has significant implications for journalism. Old media such as broadcast television and newspapers are steadily and inexorably losing viewers and circulation, he said, while the audiences for cable television and Internet news are growing. This rise of the Internet and cable has changed the delivery of news in two fundamental ways, according to Jurkowitz. First, the 24-hour news cycle has been replaced by an instantaneous cycle. There are no breaks in presenting the news on CNN or MSNBC, and information is continually updated online. Secondly, the "news hole," or amount of space available for broadcasting or publishing the news has changed. For old media, space was finite: each edition of a newspaper was limited to a certain number of pages, and each nightly TV news broadcast was limited to about 22 minutes. Now, the news hole is infinite — there is abundant space available on the Internet and cable networks run 24 hours a day. These technological changes have changed the quality of journalism, Jurkowitz explained. With 800 channels available on digital cable and information on the Internet, people today believe they have more access to information than ever before. In reality, Jurkowitz maintained, the media has become more consolidated. For example, few people realize that the New York Times owns the Boston Globe, or that the same company owns HBO and Time magazine. Although people have seemingly infinite access to information, they are not necessarily better informed. For example, Jurkowitz questioned whether C-SPAN made a difference in American life. One might argue that by giving viewers some access to the inner workings of government, C-SPAN makes for an improved civic life, but there is no empirical evidence of that. Instead, he said, public discourse is coarser; politics is more polarized; and political participation is no better. The impact of cable TV on the news universe was first evident during the first Gulf War in 1991. Americans were glued to CNN because they got to witness a war in real time for the first time, he said. Paper-based news suddenly felt insignificant, and the result is a trend among newspapers toward softer feature pieces and more lifestyle coverage. While traditional broadcast news has suffered a dramatic loss in audience share over the years, it still has higher ratings than the biggest of cable news show. Nevertheless, Jurkowitz said, it is cable news that drives water-cooler discussion. The big stories that we talk about the most are focused on and covered around the clock by the cable networks. Key elements in cable news are the big "megastories" such as the O.J. Simpson trial, or the D.C. Sniper shooting spree in October 2002. The formula for such megastories, Jurkowitz said, consists of three parts: real news, quasi-news, and commentary from experts, or "talking heads." For example, in the D.C. Sniper story, the real news was delivered whenever there was a shooting or a real development in the case. Quasi-news occurred when there was an announcement of an upcoming a press conference. In the meantime, retired homicide detectives provided commentary by giving their opinions on the case. Cable networks thrive on megastories for economic reasons. When events are happening all over the world, news organizations must pay for the travel expenses of its correspondents. A courthouse story is a much simpler and less expensive affair, Jurkowitz said.

JEFFREY DVORKIN blames the declining quality of news coverage on the drive to make money. Problems began around 1986 when head of CBS News Richard Solant revealed that the division was making a profit for the first time. When the news division becomes a profit center for a network, Dvorkin said, it begins to focus on maximizing profits. In the 1990s when large media mergers began, news organizations hired consultants who researched ways to cut costs and attract more viewers. One thing these so-called news doctors concluded was that foreign news, which was the most expensive to produce, was also what audiences cared least about. When the Cold War ended, the compulsion to do foreign news diminished, and networks closed foreign bureaus around the world. Before the arrival of the news doctors, CBS had 38 foreign correspondents in 28 cities, and they now have five correspondents in four cities. The closing of foreign bureaus had a dramatic impact on news reporting, according to Dvorkin. Today, broadcast programs often get their foreign news from organizations such as Reuters or the BBC, which provide the video footage of events. With these visuals, network reporters do voiceovers based on wire reports. Dvorkin feels that most of the time cable TV does not provide news, but rather discussions between people debating various topics. Cable news and its 24-hour news cycle has led the way for these talking heads shows to replace fact-based reporting. Over the last ten years, Dvorkin pointed out, the number of people engaged in reporting has sharply declined. Finally, Dvorkin gave an example of how communities are feeling the negative effects of media consolidation: In January 2002, a train carrying toxic chemicals derailed near Minot, North Dakota. When police tried to broadcast the emergency evacuation of the town through local radio stations, they discovered that the headquarters were actually in San Antonio, where programming originated from parent company Clear Channel. Most commercial radio, Dvorkin said, has abandoned the idea of local service. Discussion DAVID THORBURN, director, MIT Communications Forum: You are both painting a depressing picture. Do you believe that journalism in earlier eras was better than it is now? Was there ever a Golden Age of journalism before this period of decay and decadence we are in now? Or has news always been a commodity in the United States? DVORKIN: I think news has always been a commodity. William Randolph Hearst was an early version of Rupert Murdoch. Today there is greater journalistic democracy thanks to weblogs on the Internet, but that does not equal higher quality. Still, I believe the vigor of Internet journalism shows a lot of promise. What is missing now is the elite quality of news. In the 1970s, there were high expectations for the news. We must find a way to marry the high standards of elite journalism with the democracy of the Internet. JURKOWITZ: Journalism goes through cycles. After World War II, the profession matured in a way. Objectivity and knowledge had become real goals, and journalists were suddenly an elite class. Now we are in another cycle, and it is uncertain how the relationships between old and new media will play out. Public esteem for journalism has diminished. This can be seen in the changing portrayals of journalism in pop culture. For example, in the film All the President's Men (1976), Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman played reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein who uncovered the details of the Watergate scandal. They were portrayed as lofty and heroic. Decades later, the movie Dick (1999) spoofs the Watergate scandal, and portrays the journalists as bumbling and idiotic. For me, these two movies crystallize how the public perception of journalism has changed over the years. QUESTION: I see blogging as a way that citizens are participating in journalism. Although it is of a lower quality at the moment, is it exerting any pressure on media conglomerates to provide better services? JURKOWITZ: One way big media reacted to blogging was to create their own blogs. For example, the ABC News website has what they call "The Note," which has the tone of a insider's view on politics with material they would never broadcast on the air. I think blogging's biggest impact is on the mainstream journalists who are paying attention to blogs. The "blogosphere" takes credit for helping to bring down Trent Lott after his racist remarks at Strom Thurmond's birthday party. It was a story that was initially ignored or treated with little attention by most mainstream media, but was kept alive by blogs. QUESTION: Will we see the fall of organizations like the New York Times or National Public Radio, which are considered islands of journalistic integrity and quality? JURKOWITZ: A decade ago, many journalists feared that the Internet would spell the end of print journalism, but that hasn't happened. What will happen with media companies is their brand will live on, but in different forms. For example, major news organizations such as the New York Times and NPR invest heavily in their websites. Newspapers are also creating spin-off papers targeted at younger readers. The Washington Post created Express, a free daily commuter paper. Boston has the Metro, with less than 100 words per story. HENRY JENKINS, director, Comparative Media Studies: I have a follow-up question for Mark Jurkowitz on the comparison between All the President's Men and Dick. Because Dick is a spoof film, the most sacred elements of the Watergate story are bound get the roughest treatment. Perhaps a better comparison would be the drama Shattered Glass (2003), which presents a contrasting image of journalism, but not an unheroic one. It portrays Stephen Glass, who fabricated his articles, but is treated sympathetically. The film also portrays the editors and reporters who broke the Glass story, working hard to right the wrongs. Perhaps it is better to say that the press makes mistakes, but there are also good people in the profession who struggle to get at the truth. There are also alternative forces such as the Internet that are challenging the established media. Is it possible to get a more complex yet optimistic reading of the current media environment? JURKOWITZ: I saw Shattered Glass and thought it was a terrific movie, though probably not completely accurate. I used Dick as a comparison mainly because fewer people saw Shattered Glass. An unfortunate truth is that journalism movies often fail commercially, though not critically. It is hard to make a movie about the inner workings of journalism. REBECCA MACKINNON, Harvard University: Are maximizing profits and quality journalism ever compatible? The New York Times, as a family-owned company that does not answer to shareholders, is able to invest in long-term projects without worrying about short-term profit cycles. Should any serious news organization be excluded from a company that is listed on the stock market? DVORKIN:

CBS News was able to do that for many years, but that was a

time when broadcasters were expected to have a role in the civic

life of the country. There is still a value in cable and broadcast

news, such as the instantaneity and dramatic narrative they

provide, but they will never provide the kind of substantial

investigative journalism you will find in newspapers or on a

PBS program like Frontline. JURKOWITZ:

There are so many news sources claiming to have the truth that

we have lost a sense of what the common truths are. There is

a "we report, you decide" mentality. TV shows like

Larry King Live may present different viewpoints on an

issue, but there is no attempt to do real journalism, which

is finding the truth. DVORKIN: As NPR's ombudsperson, I am independent of management, so I am not speaking for them. Another clarification I want to make is that NPR has no affiliates, but member stations that are also independent; and NPR has no right or obligation to tell them what to do. That being said, I worry that public radio is unwilling to address an important issue because it doesn't want to be targeted by people who are already hostile towards public broadcasting. THORBURN: Can you comment more fully on the FCC's current campaign against indecency in the media? DVORKIN: The cynic in me believes that FCC Chair Michael Powell, who has familial ties to the Bush administration [he is the son of Colin Powell], has conveniently raised this issue in an election year.

JURKOWITZ:

I also think it has to do with politics. The legal definition

of indecency is rather vague. Part of the charade is the way

media companies have reacted. Clear Channel, which owns over

1,200 radio stations, pulled Howard Stern from six middle-market

stations where there was little money being made anyway. When

media moguls act, it is not against their economic interests.

THORBURN: I have a personal experience with this issue. In 1977, I published an article for the New York Times, about the career of actor David Janssen. When the paper launched their online archives, they required me to sign away all my rights to the piece if I wanted it included. DVORKIN: There are legal issues with freelancers. Every time someone downloads an article, the Times may have to pay royalties to the author, or reach deals on an individual basis. The law is still evolving on this issue. JOELLEN

EASTON, CMS graduate student: The New York Times

is an agenda-setting newspaper. Its website serves as a kind

of continuous news desk, and is constantly updated. Is the influence

of the print edition changing or waning because the online edition

is more frequently updated? How do online editions change the

way large papers drive the agendas of the country? JURKOWITZ: It's hard for me to understand media synergy. My feeling is that newspapers have not yet figured out how to use the Internet. Although they have established an online presence, they have yet to create supplementary forms of media that do unique things; that add value to one another. Furthermore, there is still no real model for making money from these websites. THORBURN: I believe there is a synergy. It is now standard practice for TV news programs to direct audiences to their websites for more information. This is surely an enhancement that allows people to explore many topics more deeply. This fairly obvious synergy between old and new media is being exploited by both broadcast and print news. JOHN HAWKINSON, MIT: How do you see the evolution of errata or factual corrections in the changing media? Print media such as the New York Times raises the bar for it, publishing more corrections than ever before. Meanwhile, broadcast news seems to ignore it. DVORKIN: There are different levels of admission of error. At NPR, relatively small corrections can be made online. For major errors, such as misreporting the political party of a candidate, a correction will be reported on air. We have an obligation to correct errors everywhere, even by adding an addendum to transcripts containing the mistake. JURKOWITZ: The Jayson Blair scandal forced the New York Times to hire an ombudsman for the first time. Throughout the print world, there has been a dramatic tightening that resulted from recent plagiarism scandals, but I don't know how long that will last. —summary

by Lilly Kam

|

|||