| News, Information and the Wealth of Networks |

|||

|

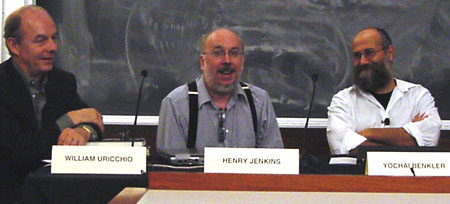

Abstract Working journalists, media critics and digital visionaries discuss the ongoing transformation and apparent decline of American newspapers. Topics to be addressed: the aging of the newspaper reader, the emergence of citizens' media and the blogosphere, the fate of local news and the local newspaper, news and information in the networked future. This is the second in a series of forums that asks the question Will Newspapers Survive? Also in the series: The Emergence of Citizens' Media (Sept. 19), Why Newspapers Matter (Oct. 5). Series co-sponsor: Ethics and Excellence in Journalism Foundation Speakers Henry Jenkins is co-director of Comparative Media Studies and the Peter de Florez Professor of Humanities at MIT. His most recent book is Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Intersect. William Uricchio is co-director of Comparative Media Studies at MIT and professor of comparative media history at the University of Utrecht in the Netherlands. His most recent book is Media Cultures, on responses to media in post-9/11 Germany and the U.S. A podcast of News, Information and the Wealth of Networks is now available from MIT World. A webcast of News, Information and the Wealth of Networks is now available from MIT World. Summary by Marie Thibault [This is an edited summary, not a verbatim transcript. Greg Peverill-Conti's forum summary is available on his blog.] William Uricchio: We're sitting here with the authors of the two most important books of the year. Both books chart a course through a profound moment of media and societal change. Both books alert us to an array of possibilities and to some of the dangers presented by emerging technologies of communication. Though this is the first face-to-face meeting between Henry Jenkins and Yochai Benkler, their books really constitute a sort of reciprocal dialogue. Henry's Convergence Culture moves from the cultural toward the social, while Yochai's Wealth of Networks moves from the social to the cultural.

Yochai Benkler offered a distillation of his arguments about ways in which the networked computer has created new markets and new forms of productive labor. Computing networks undermine or break down the traditional division between audience of consumers and a profession of those who produce information or entertainment for that audience. The computer permits every individual to play a role in the creation and circulation of information. One powerful effect of the computer: it can convert ordinary human activities into markets, as the YouTube example shows. Sharing video clips with friends becomes a billion dollar company. The emerging networked environment allows individuals to act alone and also cooperatively. Peer production is widespread -- massive cooperation among individual contributors. This structure allows for self-selection and taps diverse motivations, insights and capabilities. How we produce knowledge, who controls its creation and dissemination: these are critical questions for anyone who cares about democracy and justice. One example: In 2002, voting machines were introduced in Georgia to minimal coverage in the mainstream media. But one democracy-activist put the source code for the machines on her own site and on a site in New Zealand . After several different groups studied this, it was found that these machines were not the ones that had been certified. So, in the end, this informal system of networking individuals was more effective than the law or the mainstream media in protecting the electoral process. In this way, Benkler said, we are beginning to practice new ways of being more productive and free and equal people.

Henry Jenkins pointed out that he and Benkler agree on some of the larger implications of what seems to be happening, but are coming to these conclusions from different directions. Jenkins has researched fan and pop culture and the mass media and is now beginning to focus on forms of media that connect us: civic media. Jenkins said that we may already be living in a convergence culture because we live in a world where information makes its way through the maximum number of corporate and amateur media channels. Convergence is the meeting of top-down media organizations and grassroots interests, with mass media controlling the entertainment sector and the blogosphere responding to the mass media and altering it, splintering and selecting its content for many ideological, artistic, civic and other purposes. We live in a participatory culture and our society is going to become more participatory, Jenkins said. He made a distinction between the actual technology and what is done with that technology. An illustration of this is the difference between the iPod and podcasting. The iPod enables users to listen to music, but podcasting emerged from the technology of the iPod and used it for something new. We are beginning to explore the power of collective intelligence, the aggregation of individual minds enabled by computer networks. We're in an apprentice stage, Jenkins suggested, in which we're acquiring the skills of participatory culture and collective intelligence, learning how to deploy our new tools at first in our recreational lives. But those skills are now being utilized for civic and communal purposes by religious, military, educational groups. Uricchio: (A clip is shown of V for 9/11, a short movie that uses the premise of the movie V for Vendetta to make the controversial statement that the Bush administration was complicit with the attack on the World Trade Center.) We have a new set of realities and practices. What do we need to do to allow our citizenry to engage in this participatory culture? Benkler: I think people studying this phenomenon can't even say they are capable of educating people about this. We are beginning to develop stronger critical reading skills, as well as investigation and intelligence gathering. Research is gaining our respect. Skepticism and inquiry are the beginning of independent thought and participation. Jenkins: At the moment we're learning from each other and the learning curve is high because of collective intelligence, but I'm concerned about the participation gap, which is different from the digital divide. Some children don't have access to the skills or the tools that allow them to be media producers. Also, if you can't read and write, you can't do any of the things we've been talking about. We will be issuing a white paper in October that will outline the core skills that we think young people need to have. Although these don't necessarily need to be taught, we need to make sure everyone has these skills. Uricchio: Well, when looking at the Astroturf movement, a sort of fake grassroots movement, it is clear that along with the citizenry, the power structure learns quickly as well. Benkler: Of course, decentralized, non-hierarchical systems are susceptible to attack. As with any system, defenses are developed. Uricchio: Some people might say these structures are about enabling different cohorts, but not necessarily joining them into a cohesive larger sphere. Jenkins: Before moving on to that, it's symptomatic of a shift in power that large groups feel they need to fake a grass-roots campaign in order to be heard. This very act means that the power structures are changing. Benkler: The problem of credibility is an information production problem. Finding the fake Astroturf campaigns is part of determining what is credible. Fear of fragmentation and polarization, but it seems that things aren't too fragmented or too concentrated. We do have a decent amount of research on the ways in which people link to blog posts, Web sites. This has generated a response that this isn't democratization, just concentration. Sites cluster along interest, 10s or 100s of sites that each has 10 or so links. Interpretation of this research is that there isn't democratization, but there also isn't any fragmentation. Have we gotten so much concentration that there isn't democratization? I think we're much better off without fragmentation. Jenkins: Here is Ithiel de Sola Pool's past prediction for the future: “We will be told that we are being deluged by undigested information on a vast, unedited electronic blackboard, and what a democratic society needs is shared organizing principles and consensus and concerns. Like the present criticism of mass society, these criticisms will only be partially true, but partially true they may be. A society in which it becomes easy for every small group to indulge its taste will have much more difficulty mobilizing unity.” This describes the behavior of the flip-flopping social critics who are at first concerned with concentration and then concerned with fragmentation, and then back again. We need to be cautious of following this criticism. Uricchio: You've read one another's books. If you were to start all over again, would you make any changes? Jenkins: I'm interested in the commercial and amateur sections of participatory culture, and I think I didn't spend enough time talking about behavior outside of popular culture, but that other behavior is going to become more and more important to my work.

Benkler: I am very much a materialist in terms of my explanations. To be able to locate my work within the culture would have been helpful but would have made it hard to anchor the explanations of the changing material conditions. It would have been enormously helpful to have this to understand the intersection between cultural and material and political and economic sections. Question: I'm interested in how your models work when it comes to presenting science to the mass public. It is much more difficult to present science without having a background in science. Jenkins: Science is a really tricky area, but I think there is definitely room for experts in every section we've talked about. You have to acknowledge that presenting brain science in a top-down fashion from experts to courtroom juries who don't know anything about brain science doesn't work. Putting more information out there at least allows people to read more critically, but it is hard problem to resolve. Benkler: It's important not to compare anything to either utopia or mass commercial media. If you compare the actual number of scientific articles that disagree with global warming with mainstream media coverage of global warming, you will find that the mass media gives both sides of the argument almost equal time. This isn't translation and literacy of the science and seems like it is an effort to be fair to both sides of an argument that don't actually deserve equal treatment. But as we saw earlier, Wikipedia is a free encyclopedia that is the same quality as Brittanica. In this way, you get the translation without the mass media's inclination to simplify and make issues more or less controversial. I think this is a positive progression. Question: Both of your books end with a call to action. What are the deal breakers? For those of us who believe in the cause, where do we focus our efforts? Benkler: I think a critical deal breaker is trusted systems, a regulatory requirement that will require manufacturers to turn computers into objects that are trusted to be used as they were intended and not as their owners want them to behave. This is being driven by Hollywood because of the failure of software-enabled encryption and digital-rights management. What can we do? Open wireless networks, mesh networks may be a solution. I am a little more optimistic than I used to be because the number of companies seeing the great revenue coming from resisting these deal breakers makes me think they won't happen. Jenkins: I don't think there are any deal breakers that will end an era of participation, it seems it is here to stay. The terms of participation are being figured out right now, which is important. I think that liberal Democrats are the greatest threat to the participatory culture, because they want to take extreme steps toward limiting young peoples' relation to technology in order to appeal to soccer moms. Consumption has been criminalized and adults are trying to stop kids from taking part in the participatory culture that is central to youth socialization now. Question: I think people are sometimes afraid to exercise their political capabilities because they have seen people being arrested for file sharing. Will law ever become a bottom-up process? Benkler: This is a deep question in terms of the theory of law. Is law and the system for generating laws a progressive system, or is it reactive? There have been studies researching whether Brown v. Board of Education was really that important in desegregation, or did the Civil Rights movement lead to the more significant success of the second Reconstruction? In the last decade, law has been reactive and conservative. The reaction between social and commercial practices has been the force moving toward the new stage. I don't think this is a solved question within legal theory about the relative roles of social action and formal institution relationship with regard to the progressive change within the way society acts and is governed. David Thorburn: Is it a cause of concern to you that the statistics seem to imply in a generation or two there will be no more newspaper readers? Will there be a place for counterpart institutions to newspapers within this participatory culture? Jenkins: As someone who was trained as a journalist years ago, I am deeply concerned with their fate and I think they continue to play a vital role in our culture. The current situation is healthy with the centralizing power of mainstream media and the diversifying power of the blogosphere. If I was a journalist, I'd study the blogosphere to try to figure out what groups and issues I'm not covering. The blogosphere is still very dependent on the mainstream media to give them the content they talk about. Thorburn: Don't you think it would be helpful if the terms we used in this debate didn't already come with connotations? Of course “participatory” is good and “top-down” is bad, but I don't think this gives a fair description of the contributions regional or national newspapers like the New York Times or the Washington Post make to our society. Jenkins: I'm certainly not suggesting citizen journalists will replace professional journalists because there is training, resources, and ethics to take into account. Newspapers aren't purely top-down, but the blogosphere is succeeding because it is identifying points that aren't being touched on by newspapers. Of course, it isn't possible for one newspaper to cover everything, so I think having the blogosphere adds to the variety of information we receive. Benkler: The New York Times, the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, are top-down and vehicles of the elite because we place great value on expertise and careful thought. Elites of wealth, intelligence, power, use this to set a common conversation among each other. Television changed newspapers, the Internet changed newspapers, and they'll have to keep transitioning. Citizens outside of top-down media can become professionals who are committed to journalistic values. The Talking Points Memo website by Josh Marshall is an example of this. Marshall makes a point of proving that he can make a living without making millions and by practicing professional journalism. Question: It seems like the future will be a kind of hybrid between mass media and citizen media. What will be its nature? Jenkins: This discussion can now be out there for those restricted geographically from being here physically. Webcasts and OpenCourseWare (OCW) have done that. We can play the part of a go-between to tap diversity of Web and amplify its message. We now have the obligation to be educators of a larger public in this participatory culture. Benkler: I think OCW was especially important because it tried to further MIT's role as a free public educator at a time when other universities were looking to increase revenue. Jenkins: I believe in OCW's mission, but MIT's leadership is flawed because it is unwilling to make OCW entirely fair use. We should be defending a notion of fair use that allows materials to be widely circulated. I want to be able to represent fairly my use of other people's materials in my courseware. We haven't gone far enough with thinking about what it means to be the center of a participatory culture. This is why I haven't put my courses on OCW yet.

|

|||