| What's New at the Media Lab? | |||

|

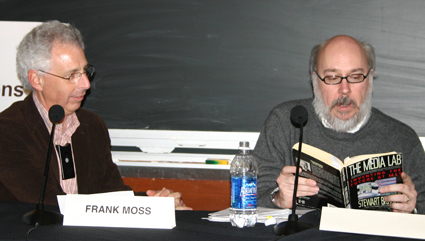

A conversation between Frank Moss, new director of the Media Lab, and CMS Director Henry Jenkins about ongoing projects and inventive digital applications at MIT's legendary laboratory. Speakers Frank Moss is director of the Media Lab and the Jerome B. Wiesner Professor of Media Technology at MIT. His citations include Ernst & Young's Entrepreneur of the Year award and Forbes Magazine's "Leaders for Tomorrow." Demonstrations A podcast of What's New at the Media Lab? is now available from Comparative Media Studies. A webcast of What's New at the Media Lab? is now available from MIT World. [this is an edited summary, not a verbatim transcript] by Greg Peverill-Conti and Marie Thibault

Moss said often starts conversations about the Media Lab by asking people how much technology has impacted them at a deep level; and whether they think their lives are better today than 20 years ago. In his experience, very few people believe that it is. He attributes this to worries about the future and the stress this can cause. When he was growing up, people were excited and optimistic about the future. Today, despite the wonders of technology, people are worried. He sees an opportunity to focus the Lab on helping to create a better future; the best starting point is to help people who are disabled, disadvantaged, or disenfranchised. By creating transitional technologies for these communities, new ideas will be able to migrate up into more general applications. This is fundamentally different from the typical model where attempts are made to adapt technologies for the disabled, disadvantaged, and disenfranchised. Several of the technologies that were demonstrated later in the evening illustrated Moss' point. Again using Brand's book as a starting point, Jenkins asked Moss to comment on the aims of the Lab and to share his thoughts on its history. An important point to remember, Moss pointed out, is that the Lab is funded through corporate sponsorships – which makes it different from the rest of MIT. Negroponte believed that companies would support the Lab simply to have the opportunity to spend time and rub shoulders with the staff and the students. This was based on assumptions of the value of serendipity – and there have been some wonderful examples of this: sensors for passenger side airbags based on work done for the magicians Penn and Teller is just one. During the 80s and 90s, when companies were thinking about the digital future, this opportunity for serendipity was tremendous. But after 2001, companies began to need to justify the cost of sponsoring the Lab. This was a problem since the Lab wasn't created to develop commercially applicable technologies or to deliver a measurable return on investment. It has made it a challenge to maintain the open, creative, and non-directed environment that has made the Lab what it is today. Moss is realistic but optimistic about these challenges. One of the reasons for his optimism is that, for economic reasons, many companies have decreased their commitment to basic research. This has made the work being done at the Lab even more important. Jenkins next asked Moss to comment on another passage that claimed that the Media Lab chases the horizon; not what works but what might work. Moss responded by saying that the Media Lab is successful if people find themselves asking questions that they'd never thought of asking before. The only mistake people can make is not asking the right questions. Jenkins moved on to discussion of the role of the Lab in “inventing the technology of diversity” or, as some fear, “the technology of perversity,” because of claims that the Lab and technology were creating culture. Some – particularly those in the humanities – disagreed with this idea when Brand's book was first published.

Moss believes that the Lab serves a useful purpose by allowing the exploration of the different ways people and ideas can come together. He conceded that in the past there may have been people who viewed the Lab as an island but insisted that he supports the idea of collaboration and the need to reach out since the Lab and the students benefit from this approach. The Lab's role at MIT is to provide students with a unique experience. Everyone, from Moss to the corporate sponsors to the faculty to the students are committed to creating contacts and a collaborative environment. Jenkins said that Negroponte had to fight to use the term “media.” He wanted to know what Moss thought the “media” in Media Lab stood for. At some point, Moss said, one has to stop trying to make sense out of names. That said, he's heard “media” described as applying technology to mediate experiences between people and technologies. Moss believes that there are a growing number of new technologies that are allowing that mediation be more of a meditation on the relationship between people and technology. Jenkins next asked about the $100 laptop, one of the more famous inventions to emerge from the Lab. It was started in 2005 and was based on the idea that the best way for people to learn is by doing. Negroponte concluded that the best way to do this on a large scale was to put technology into the hands of kids. What he created wasn't just a technology idea but an economic one as well. What makes this amazing is that it is really about to happen. While the project was conceived in the Lab, MIT felt that the production should be spun off and the result is One Laptop Per Child. While OLPC missed the $100 target (the devices will cost $125), it has reached agreements with many governments around the world. For all of the excitement, Moss explained, there has been controversy – with some questioning if this is the best way to spend the funds involved. Moss believes that there is great value in the program and pointed out that by creating technology to help these largely disenfranchised communities, ideas have been developed that will be appearing in commercial laptops over the next five years. A few examples of these include: mesh networks for unrouted communication, daylight readable screens, advanced power management (the OLPC systems can run for up to eight hours on battery power) and a rethought user interface. Some of the other aspects of the system are the flexibility of its physical configuration and the fact that it is comfortable and approachable for kids (thanks to its design and colors. Some of the concepts behind the OLPC project – the design principles, the interface, the relationships it assumes between people and its simplicity – are all reflected to one degree or another in the three demonstrations that Moss introduced. The first demonstration was given by Adam Boulanger on musical intervention. Boulanger believes that one of the areas where technology has failed is in its ability to help people become more expressive and creative. He is working on creating technology to help break this mold by providing a system of thinking that redefines what it means to be creative. The Hyperinstruments group with which he is involved started by fitting virtuoso musicians w/ sensors that allow for the creation of new expressive opportunities. They next applied themselves to bringing these types of technologies to physically and mentally disabled people at Tewksbury Hospital. There people worked with Hyperscore – a composition tool that allows people to “paint” melodies, after which a simplified harmony is applied. Boulanger played a video from the program and compositions created by 10-year-old children. He described the work they are doing as providing a creativity prosthesis – an apt description. He reported that the musical therapy the program enabled creative new opportunities for leadership and interaction that would not have been otherwise possible. Boulanger saw far greater possibilities for this program in the future. He can imagine a day when these creative and social tools could be coupled with science to improve peoples' lives. One example he offered were musical games that could also function as cognitive tests that would measure how people are developing and improving. Creativity, he believes, is going to become a crucial component for the future of health care. Moss pointed out that there were a number of other projects happening in the Lab to assist people with autism and other mental illnesses. While much is being spent on finding cures and rehabilitation, Moss believes that it is equally as important to find ways to improve the quality of life for people whose conditions will not be cured. The second presentation was on Smart Cities by Ryan Chin. The goal of the Smart Cities group is to understand how cities might be made more functional and livable. One element of the project is the City car – a collaboration between the Lab and GM. The City car is a foldable, efficient, shared vehicle that is designed to rethink the relationship between the car, the city, and public transportation. The car is intended to deal with some of the mounting challenges and realities of the city: urban density, congestion, and pollution. The City car takes advantage of the increasing connectivity by making the car a connected element of the city. It provides easier access to the resources of the city and recognizes that the infrastructure of the city isn't going to change. It complements the realities of the city in terms of things like population density, mass transit routes, and parking. Some of the interesting elements of the car are that it is shared, electronic, omnidirectional, and stackable. When someone needs one they simply swipe their credit card. When they are finished they return it to a stack where it is recharged. How would these vehicles affect the city? Given their small size (only a few feet long when folded) they would use parking far more efficiently (a typical Manhattan block can accommodate approximately 83 traditional vehicles, but has room for more than 500 City cars), freeing up space for other uses. They also represent a great deal of battery capacity that could be used in a variety of ways – in motion as transit; at rest as a source of power for the grid. Because they are shared the cars can be personalized and because they are connected they can act as a social networking tool or a concierge. The idea of the car as a shared service is not easy for the auto industry to think about. Moss pointed out that the students weren't only dreaming up these types of things in the Lab, but were building them there as well, saying that the Lab provides access to an incredible suite of tools and systems.

The final presentation was on Biomechatronics by Hartmut Geyer. The Biomechatronics group works in two areas. The first is to develop a fundamental understanding of how legged systems work and then to apply that understanding to the development of prosthesis or human augmentation systems. Geyer discussed the Rheo knee prosthesis, a passive device whose major function is to dampen the impact of walking and to use the energy of the impact for forward motion. He showed a video of the knee in action. As interesting and effective as the knee might be, he explained that it was not an active replacement – that is, it does not truly integrate with the human nervous system. The next prosthesis he showed was an active ankle that does depend on a true human/machine connection. He demonstrated how the Lab was conveying the planned movements of a wearer's phantom limb into signals to which the connected limb could respond. The current state of the art is to send user nerve signals to the prosthesis but in the future, electrodes implanted into the nerve fibers might able be able to send sensory information from the prosthesis back into the nerve. All of this is based on research being done in the Lab in biomechanics and motor control. Moss said that there is going to be a much broader impact of technology on humans and that it will essentially redefine the idea of disability. Discussion Question: How are you getting people with disabilities involved in Media Lab projects? Boulanger: My group is forming collaborative groups within MIT but are also looking to the community; to state hospitals, families, etc. Many students are out talking with parents and support groups to get their input and involvement. This is something that has changed very quickly about the Lab. The ability to do this didn't exist in the past. Moss: There is a lot of interest from patient groups and support groups to test and measure the types of technologies that are being developed in this area. Question: How does the City car deal with crashing into an SUV and how does a driver actually return it to the stack? Chin: The car would essentially park itself when it was brought within a certain proximity of the stack. The goal is to make the stacking and recharging process as simple as possible. In terms of parking – this is really an issue of perception. The City car has been designed to be a safer crash structure than a traditional vehicle. It's an important issue, though, and one that could lead to different types of solutions. One such solution may be to permit only City cars within specific city zones. Question: How does the car serve as a multi-purpose space? How does it deal with different transit models? Chin: The project decided to focus on the city; but there could be a suburban version that one might take home at night and leave at the train station in the morning. Question: How does the music software convert the colors and lines into music and how does it deal with noise (unintended sound)? Boulanger: More information is available online, but the shapes and colors both have meaning which the software uses to create harmony. In terms of noise, the kids are simply expected to play and to think about what they are hearing and if it is something they like. They usually understand the system pretty quickly. Question: Has any thought been given to the social meaning of the City cars? For example, in LA there is a stigma associated with using public transit. Chin: A lot of thought has been given to the issues of personal ownership; there is a place for technology to mediate the ideal of personalization. Car sharing is quite an old idea – the question is how one receives mobility and accessibility; can mobility be democratized? In South America , for example, very few people have mobility. Providing a means to reduce travel time would improve the quality of life of many South Americans. Question: Is the Media lab doing anything with media? Moss: The Lab is looking at issues of the media in terms of expression. It is not as pervasive as it once was but it still exists. Question: How would the City car provide storage for the things people need every day – groceries, strollers, etc? Could drivers use a mini trailer?

Chin: The car has been designed to accommodate a maximum of eight grocery bags. Virtual towing is also an option. Because the City car is a digitally controlled vehicle one driver would be able to drive multiple vehicles at once (of course there could be some legal issues to overcome with this approach). Finally, because the car is a shared space people may find that they don't need to store so many things in their car. Question: Have there been any measurable results in using the musical application with people with mental illnesses? Boulanger: The possibility of culture change in a place like the state hospital needs to be researched; but based on what has already been seen, the musical application is being prescribed as a treatment. The results have been in the form of changes among the patients that can be hard to measure – how people relate, how they feel about assuming roles of leadership, etc. These types of results are not uncommon; but what is different is the use of technology to mediate the musical experience. Question: In the case of the car and laptop – what kind of resistance do you expect to face from cities, parking lot operators, etc. Moss: There are always reason to protect the status quo. The purpose of the Lab is to encourage and provide an environment for people to think differently. Yes, there is resistance, but the role of the Lab is to inspire people to think differently Question: What are you wearing around your neck? Moss: The director of the Media Lab can't go out without a gadget; and this one is part of a project on the dynamics of people in groups. It measures speech, movement, etc. to analyze social interaction. --photos by Greg Peverill-Conti | |||