Haiti

Pic La Selle (8,793 ft)

Eric and Matthew Gilbertson

Date: August 23-24, 2013

Left:Crossing back into Dominican Republic Right: Our friend Tommy

More pictures here: http://mitoc.mit.edu/gallery/main.php?g2_itemId=396601

28 miles biking

20 miles hiking

10,000ft total elevation gain

0 other white people ('blancos' or 'blans')

“Bonjour, avez-vous l’eau? Nous sommes tres soif” [Hello, do you have any water? We’re very thirsty], Matthew asked the Haitian woman in front of us, hoping she understood French. Somehow we’d already drunk a gallon of water each in the hot, dry Haitian mountains, and our bottles were now nearly empty. We’d passed the last stream hours ago and feared there would be no more water any higher up. The meager amount we still carried would certainly not be enough to get us to our objective – Pic la Selle – and back.

Luckily we’d stumbled across a small village nestled between two hills halfway up Pic la Selle, and spotted a woman squatting down outside one of the mud-walled huts sorting corn meal in a large wooden bowl. Surely she knew where to find some water, we reasoned. Unfortunately we didn’t speak Creole, but we hoped it was close enough to French that she might understand us.

The woman just stared quizzically back up at us, though, like we were some aliens from outerspace. I got the impression she’d never seen white-skinned people before. This village was, after all, very remote – probably a 5-hour hike from the nearest road over very steep terrain, in a region of Haiti that rarely, if ever, sees a tourist. The village itself looked like something from the stone age, with huts made of mud walls, stick roofs, and no hint of new technology from the past 200 years.

Matthew repeated the question, this time pulling out a nearly-empty water bottle and shaking it, then acting like he was trying to drink from it. This time the woman got up and walked back into her hut. She soon returned with a smile on her face and a big pitcher of water.

“Oooh merci, merci!” [thank you, thank you!] we both said.

We held out our water bottles and gratefully accepted everything she could pour in. When the pitcher was empty we dug through our backpacks and produced some bagels and granola bars, which we offered to the woman as payment. She gladly accepted, laughing as she took the food from us back into her hut. We could have offered money, but I doubt she would have known what to do with it. With enough water to get us up the mountain we left the village and continued our climb. When we were out of sight we popped in some iodine pills in order to sterilize the water. "I don't know what's in this water," Matthew said, "but it's getting a generous dose of iodine - we don't want any cholera here."

--

DRIVING THROUGH THE DOMINICAN REPUBLIC

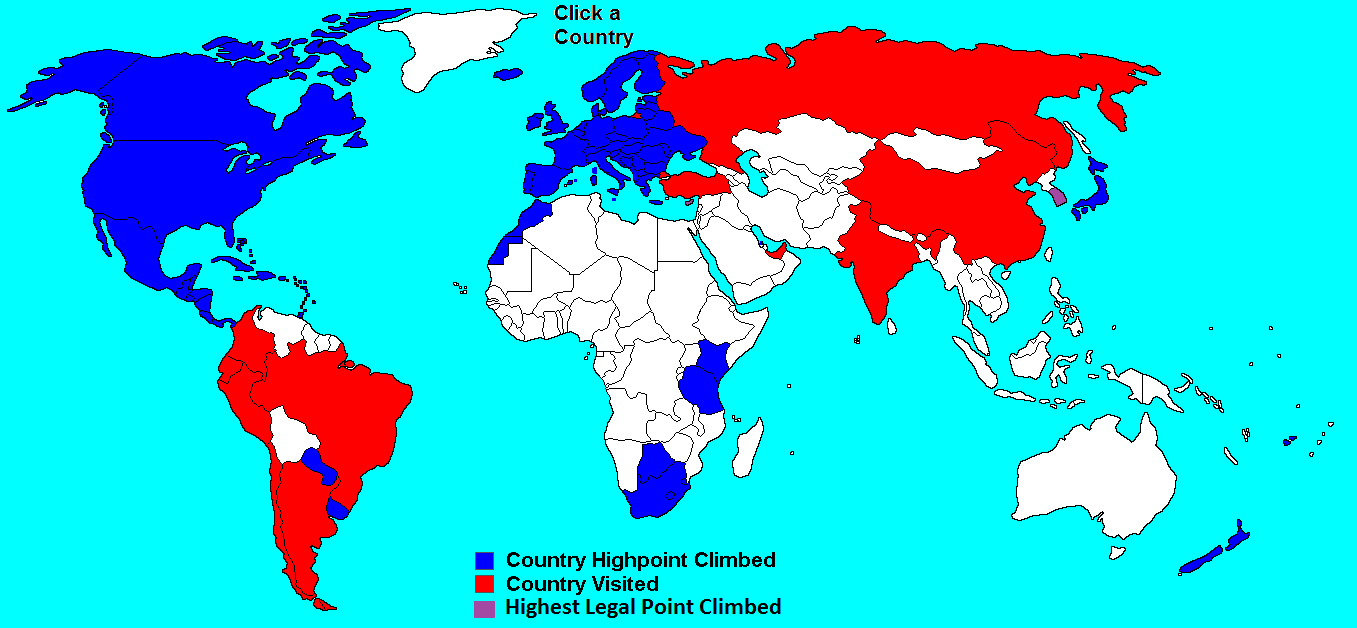

Our journey began at 2:30am that morning when our flight landed in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. We were on a mission to climb the country highpoints of Haiti and Dominican Republic, and determined a long weekend was just enough time to accomplish this goal.

We had reserved a rental car in advance through Alamo and had even called to confirm they would be open at this hour, but, as we’d come to expect in the Caribbean, Alamo had no cars available when we showed up at the counter. After some negotiations we determined one car rental agency – Moderno – in town had a car and was open at this hour, and a Hertz employee was nice enough to drive us there.

By 4am I finally got behind the wheel of a silver Chevy Aveo and we took off into the night. Our first order of business was to fill up on gas. The tank somehow read sub-E, but the rental dealer assured us a gas station was nearby and we could return the car with whatever amount of gas we wanted. Of course he would say that – whatever amount of gas we left in the car would be free gas for him. We suspected he must siphon out the gas after every rental car is returned, then drop just barely enough back in to get the car to the nearest gas station, ensuring that the customers will always return the car with more gas than it started with. We both vowed to return it as close to empty as possible.

We made it to an open gas station, filled up, and started driving west on highway 2 to the Haiti border. I quickly learned some important lessons about driving in the DR:

1. Red traffic lights at night effectively mean “slow down”, not “stop”. Watch out.

2. Always drive in the left lane of a multilane road, even if you’re not passing or going fast. Motorbikes without lights, broken down trucks, and darkly-clad pedestrians roam in the right lane.

3. Be prepared to be blinded by every oncoming vehicle. Basically every car either drives with its brights on the whole time, or has specially-modified lights that have only one setting – blindingly bright.

By 6am the sun came out and the driving became considerably easier. We passed through the towns of Bani, Azua, and Neyba with Matthew expertly navigating. We cut across the north side of Lago Enriquillo -the lowest point in the Caribbean at -148ft – and then suddenly the road in front of us disappeared into the lake.

“Hmm, this could be a problem,” Matthew said, looking at the GPS. “This road is supposed to be the only one into Jimani, the border town, from this side of the lake.”

“It looks like the whole lake has risen 20ft, based on the half-submerged palm trees,” I replied.

We turned around back to the nearest town, and noticed a spraypainted sign reading “Jimani” with an arrow pointing onto a rough dirt road. A new road was apparently being constructed around the lake, but hadn’t been paved yet. We turned onto it nevertheless, and cruised into the border town of Jimani by 10am.

THE PLAN OF ATTACK

The driving component of our climb up Pic la Selle was now complete, and we would be relying purely on human power for the rest of the climb. Our plan was to bike across the border into Haiti until the roads were no longer bikeable, then hike the rest of the way to the summit. We’d spent considerable effort formulating our plan of attack on Pic la Selle, and had thrown out many other options. We could have flown into Port-au-Prince and rented a car to drive close to the summit, but the US State Department had a strong warning against any travel near Port-au-Prince, and the mountain roads looked impassable except by foot or motorbike. We could have hired motorbike taxis when the road got rough, but it would be difficult finding a taxi for the return journey, or arranging a time to be picked up when we had no idea how long the hike would take. We could drive over from the DR border, but rental cars were prohibited from crossing into Haiti, and we’d heard stories of local drivers having trouble crossing the border as well.

We eventually settled on flying down with foldable bikes (that fit in normal checked luggage suitcases and thus didn’t incur the usual $100 bike fee each way), biking across the border and roughly 14miles until the roads stopped, then hiking the remaining 10 miles up to the summit from the north. We’d only read a couple trip reports of anyone climbing Pic la Selle, and they all climbed from the west. However, satellite images appeared to show faint trails winding up close to the summit from the north, and this was the most convenient route for us approaching from the Jimani border crossing.

OUR FRIEND TOMMY

I pulled the car over at a small park in the middle of Jimani and we started assembling our bikes at a bench. Unfortunately we’d had to disassemble them a little bit back in Boston to fit in the suitcases. After five minutes a group of three elementary-school-age kids walked over, stood right in front of me, and stared at the bike. I tried greeting them in Spanish, French, and English but they just stared blankly at me and then looked back at the bike. I went back to work, but then more kids started walking over. Pretty soon we were surrounded by 15 kids staring at us and our bikes. I think the kids were bored because school was out for the summer, they were curious about two white people who’d come into a town that rarely sees tourists, and they’d never seen bicycles quite like ours, with their little 20-inch wheels and collapsible seat and handlebars.

In an effort to break the break the ice a bit, Matthew decided to enlist the help of one little boy in inflating his tires. Matthew had removed his tires from the rims and had carried them on the flight, in order to make the bike's checked bag appear as small as possible. He connected his bike pump to one tire and pumped it a few times, then gestured to the little boy to follow suit. The boy, without hesitation, picked up the pump and started pumping. Everyone around the circle began to smile. We had come to realize that pumping up a bike's tires was a universal concept - the little boy knew exactly what to do even though not a single word had been exchanged. He pumped it up dutifully, pausing periodically to check the tire pressure with his thumb. Matthew continued assembling the rest of his bike while the boy - a welcome addition to our pit crew - inflated the other tire.

One guy about my age started asking me what I was up to (in Spanish), and offered to help us cross the border and to find a safe place to park our car at the local police station. We finished assembling the bikes, then tossed them in the trunk and drove over to the police station with our new friend Tommy. We saw five police officers sitting outside on the front steps killing time, and walked out to talk to the chief. He said we could park our car in front of the station overnight and it would be safe.

As we walked back to the car to pack up our bags all the police officers followed. They obviously were pretty bored and were curious what two gringos with weird-looking bikes were doing there in Jimani. Again we had a big audience as we packed up our bags. On Tommy’s recommendation I slipped the chief of police a ten dollar bill as we left, in hopes that he might keep our car extra safe. We then got on our bikes and pedaled to the border, following Tommy on his motorcycle.

THE HAITI BORDER AT LAST

The Haiti/DR border is the roughest and most chaotic border I’ve ever seen. Matthew and I are used to the US-Canada border crossings where you simply drive up to a window, hand an agent your passport, he scans it, hands it back, and you’re on your way. We’ve driven across some chaotic borders in Central America, but nothing compares to entering Haiti.

As we pedaled past the outskirts of Jimani the road quickly deteriorated to white gravel, with motorbikes zipping past us in each direction. Up ahead loomed dozens of tractor-trailer trucks parked on the side with a big cloud of white dust hanging in the air, and a bustling market with people selling food and trinkets.

Past all the commotion stood a large blue gate surrounded by armed border agents. One door of the gate we severely mangled, like a truck had driven into it, and the other side had no door at all but instead a large chain across.

Tommy waved us over to a cluster of buildings on the side, took our passports and some money, and emerged with official paperwork saying we could leave the DR. We’d learned from crossing borders in Central America that it’ll save considerable time and hassle to have a “helper” person fill out the correct forms for you and cut to the front of the line to hand them to the correct border agents. In this case Tommy didn’t immediately ask for any money, but instead said he would meet us here the next day on our return to the DR and help us again, then ask for ten dollars apiece. We thanked him and headed for the gate pushing our bikes.

THE “HELPERS”

The agents waved us through, and we were quickly approached by two Haitian men hoping to help us through the rest of the border. It turns out this was only the first of four gates we had to pass through. It’s not completely clear, but I think the gates represented customs, then immigration for leaving DR, then customs then immigration for entering Haiti.

We accepted the new “helpers’” offer, and made it through the next gate after getting a new passport stamp. At gate number three they said we needed to register our bikes' serial numbers with the officials. This seemed very suspicious, but we dutifully wrote down our bike serial numbers and paid the little fee to leave that gate. The final gate was the most difficult. We suspected the “helpers” were ripping us off on the last fee to enter Haiti, and argued for ten minutes until they relented and charged us only the real price for the final paperwork.

With all the paperwork in hand we approached the final gate. A tough man holding a chain across the gate blocked our path and would not let us through. He argued with our helpers, and then the helpers just ducked under the chain and motioned for us to follow. The chain-holder man was furious, but we ducked under as well and quickly jogged away. If we’d been in cars or on motorcycles he could have held us back and asked for money, but with our bikes we’d easily snuck by.

We were officially in Haiti! Now multiple other “helpers” approached, all wanting a piece of the gringo money pie. Our helpers demanded $40 for their services. I tried to negotiate, but they wouldn’t budge. In the end I pulled out 1000-peso note (worth about $20), handed it to one of them, and we quickly took off on the bikes. They all were too busy yelling and arguing with each other about how to split up the money that they didn’t bother to chase us and we made a clean getaway.

BIKING IN HAITI

“Why couldn’t this border crossing just be simple, like on the US borders?” Matthew yelled back to me.

“Because then ten different people couldn’t each get money from tourists like us,” I replied.

We’d hoped, based on the satellite images, that the road into Haiti would be paved, but that was unfortunately not true. We carefully navigated over the rough gravel road on our little foldable bikes, praying no sharp rock would puncture our tires. It was noon by now and we began to notice the sun glaring down on us in the dry 90-degree air.

Just outside the town of La Source we turned left onto an even rougher gravel road leading up into the mountains. This time we were forced to walk the bikes. After an hour we met up with a more major road. It was labeled Route 102 on the map, but the fancy name signified only a minor improvement in road quality. We took a water break under a tree and each chugged a liter of water. Motorbikes passed silently rolling downhill, their motors off to save fuel. Huge trucks rumbled uphill with dozens of Haitians hitching rides on the back. We wished we could catch a ride on one of those trucks, but agreed the bikes would be worth the effort today for the ride back down tomorrow.

On Route 102 we were able to ride the bikes again, and slowly made progress up the hill to the small village of Lastic Le Roche. Matthew had marked our planned route on the GPS, and here we turned down a side road and dropped into a big river valley where the road petered out. The river valley was filled with fist-size rocks, making it impossible to ride the bikes and we were forced to dismount and push them.

THE BLANCOS

There were many small villages on the side of the river valley, and we soon started hearing “Blan! Blanco!” yelled from above [white, in Creole and Spanish]. Little kids would run up to get a view of the strange new characters entering the valley, and for some reason each little kid felt compelled to yell “Blan” or “Blanco” at the top of his lungs. I thought it was kind of funny at first, but then some of the kids started throwing rocks at us. I wanted to throw rocks back, but we instead started jogging to get away.

Farther up the valley some older kids on Motorcycles spoke a little bit of Spanish and told us it was impossible to bike up the river and that we should pay them to take us up on their motorbikes. We were determined to climb under our own power, though, and told them no thanks.

Higher up the valley we passed people washing clothes in a small trickle of river, and without fail every person we passed stared at us or yelled “Blan!” or “Blanco!” Eventually we reached the section of our planned route where we needed to leave the river valley and start climbing. That meant we needed to ditch the bikes.

HIDING THE BIKES

“If anyone sees us hiding these bikes, they’ll certainly steal them,” Matthew warned.

We stumbled upon a bushy area with no people in sight, though, and quickly folded up the bikes. Matthew plunged into the bushes with bikes and lock while I stood guard outside. I soon heard some kids approaching and walked toward them before they could get to the bike location. I tried talking to them to distract them, but they kept walking towards the bikes. Just then Matthew emerged from the bushes.

Thinking quickly, Matthew acted like he was zipping up his pants and buckling his belt, as if he had just gone to the bathroom in the woods. The kids pointed towards the woods and shouted something. Matthew shouted back "toilette!" I think the kids believed his show, because they started following us up the hill instead of inspecting the bushes Matthew had just walked out of.

THE GUIDE

We walked on a trail through a small village, then dropped back down to the river and started walking up the valley again. A young man caught up to us in the river valley and asked where we were going. (At least, I think that’s what he was saying in Creole, since it kind of sounded like French). "Pic la Selle," I replied, pointing up at the mountain.

Through a combination of French and hand gestures, he conveyed to us that the river valley was the wrong way, but that he could guide us up the mountain.

“Let’s follow him for a little while and see where he takes us,” I suggested.

We followed the young man back up out of the river bed and soon met up with a nice trail traversing the hillside. After ten minutes he abruptly turned around and asked for money. Matthew handed him the equivalent of one dollar in Haitian money, seeing if that would appease him, and it seemed to work. By now the river below had narrowed into a deep gorge with cliffs on both sides, and we were relieved to have followed this man on the correct route.

We dropped back down to cross the river, and then began steeply climbing. Again the young man turned around to ask for money, but this time we hesitated.

“He’s going to keep asking for money the whole way, and we don’t need him because we have the route already marked,” I said to Matthew.

“Yeah, just tell him we don’t have any money,” Matthew replied.

I said we were out of money, but I offered him a granola bar instead. He smiled and waved goodbye and started walking back to his village, without even accepting the granola bar. I was happy to be rid of this guy, but soon other villagers caught up to us on the trail and stopped and stared. There were little kids with bags of clothes balanced on their heads, and a couple of men carrying loads. They acted like they’d never seen white people before. We began to realize that all the trails we’d seen on satellite images were the routes between villages. There were no roads up in the mountains – people just walked everywhere.

We stopped to rest and let the villagers pass, then continued uphill. Surprisingly the trail had quite a few switchbacks, though it was still steep. I suppose since people take the trail every day they’ll invest some time to make it a follow a good route. As we wound up the mountain we noticed there were hardly any trees anywhere, compared to just across the border in DR where forests covered everything. The problem was that Haitians are so poor they rely on wood fires for all cooking, and most of the land has been deforested as a result. At least the lack of trees let us have a good view all day.

FOOD FOR WATER

As we climbed higher we came to the realization that we had already drunk most of our water. We’d each started with five liters, hoping that would be enough to last us through the next day, but the air had been so hot and dry that we’d drunk much more than we’d expected. We were unfortunately much higher than any river valleys, but soon stumbled across a village at the top of the hill. Luckily the villagers were nice enough to trade us water for some of our food, and we continued hiking.

We climbed steeply up more trails, and topped out on a large plateau with cornfields in the middle and several huts on the edges. Cows and goats roamed in the grass on the edge of the fields, and a few men walked by us towards the huts, probably heading home for dinner after a day in the field. This village looked completely self sufficient. They probably lived off the corn they grew and the animals they raised. It would certainly be difficult for any food or supplies from the nearest road to reach this village, given how long it took us to hike up.

We could see Pic la Selle tantalizingly close, but unfortunately we had to drop a thousand feet into another valley before starting our final climb. At the bottom of the valley we stopped to rest and eat a little food.

THE FINAL PUSH

“I sure hope we don’t have any more than two thousand feet of climbing left,” I said to Matthew.

“Well, actually we’re at 5000ft now,” Matthew said, consulting the GPS, “and the summit is at almost 9000ft, so we have 4000ft left to climb.”

“Dang! That’s like we’re climbing Mt Washington!” I exclaimed.

We’d hoped to see sunset from the summit, but with another 4000ft to climb and only an hour of daylight it didn’t look likely. We kept climbing, eventually leveling out in some cow pastures before climbing into some genuine forests.

“Well, we must have passed all the villages,” Matthew observed, “the only reason there would be trees here is that it’s too far away from the nearest village for people to walk to get firewood.”

By now the sun had already set and we had to hike by headlamp. We wound up the steep, gravelly trail for another hour until we reached a saddle between two peaks. The trail continued down the other side, but we turned off to the left and began bushwacking the final leg to the summit.

At 8:30pm I spied a small concrete block in the woods, and there was no more mountain to climb. We were on the summit of Pic la Selle, the tallest mountain in Haiti and our 52nd country highpoint! There was no sunset view, but I could see some lights of Port-au-Prince through the trees in the distance. There was actually a small summit register on top, and the last person to climb had been three months ago in May.

We had brought all our overnight gear with the hope of sleeping on the summit, but unfortunately we were both nearly out of water again. We decided it would be best to make it as far down tonight as we could to avoid hiking in the heat of the sun, and then try to find a village the next morning that could give us water. Matthew led the way down the summit, following the same way route we’d climbed.

UNEXPECTED WATER

“Wait a minute,” I said, “these plants have puddles of water on their leaves. I’m going to drink some.”

“How is there water here?” Matthew asked, “It didn’t rain today.”

“Must have been clouds passing through, but I don’t care,” I replied after slurping up some water.

We were now on the lookout for the special agave-type plant that had the perfectly-shaped leaves for collecting water. There were actually quite a few in the forest, and we managed to fill a nalgene halfway full of water. That would have to be enough to get us through the night. We soon reached the trail and descended until we reached the first flat spot on the grassy hillside. It was pretty late now, so we set up the tent and quickly went to sleep.

THE BUCKET KIDS

I expected to sleep in late the next morning after having essentially not slept the night before, but we both rose at sunrise and started packing up. Before we were done two little kids popped up from the side of the hill, each carrying a big bucket. We reasoned they had to be fetching water, so Matthew approached them and asked “avez-vous l’eau?” [do you have any water?]

They said “oui,” so Matthew quickly grabbed a big water jug and followed them around the mountain. Pretty soon, though, they just stopped and stared at Matthew. Matthew repeated his question about water, but this time they just said “no.” Maybe they were nervous with this weird white-skinned person following them, or maybe they had some other use for the buckets. Either way Matthew returned water-less and we quickly started hiking back down the mountain.

MORE FOOD FOR WATER

We soon reached the dry valley and climbed back up a thousand feet to the village on the plateau. By now we were one hundred percent out of water. We walked toward some huts and began asking people for water, holding out our empty jugs. They gladly poured a liter into each jug, and we handed over the last of our bagels as payment. I’m not sure if we needed to pay them, but we knew it had probably taken them a lot of effort to get that water to the village, and they might be reluctant to give it out for free. When we were out of sight we stopped to throw in some more iodine tablets. The water was crystal clear, but we gave it twice the recommended dosage of iodine because we didn't want to take any chances.

Several kids followed us to the edge of the plateau as we hiked away, but then we were on our own. The descent went fast, and soon we were back in the river valley.

A REFRESHING SWIM

“I know Haiti’s about the last place you should swim in the water, but that water looks so fresh and it’s so hot outside I just have to jump in,” Matthew said. "The benefit of a cool dip outweighs the risk of schistosomiasis."

We both agreed, and had a very refreshing dip in the water. I bet plenty of other tourists would enjoy the trails we hiked on, especially after seeing the awesome river gorge that we swam in. But the area is just so hard to get to and has no tourism infrastructure that I doubt many hikers will visit it any time soon.

Refreshed and back at capacity on water, we continued hiking down the trail until we reached the village near our bikes. We were greeted by the familiar chorus of “Blanco!”, but Matthew also heard one little kid yell “velo!” [French for 'bicycle'].

“Uh oh, I bet they found the bikes,” Matthew said. “We didn't pass through this village with bikes, so why else would that kid mention 'velo'? Hopefully they didn’t break them and we can just buy them back, or trade for them. I'd give it a 50% chance that the bikes are still there.”

We rounded the corner to the bushes and Matthew plunged in. In a minute he came back out with both bikes! Those kids must have really thought he’d gone to the bathroom in the bushes, and that must have kept them away.

DESCENDING IN STYLE

Now we got our reward for the grueling hours spent pushing the bikes up the valley. Despite the fist-sized rocks in the path, the valley was steep enough that we could actually ride down the entire way without walking the bikes. The foldable bikes were certainly not meant for such abuse, and I think we pushed them to the limit on what they were capable of. It was certainly a lot of fun blasting down the river valley so fast. This time nobody even had a chance to yell “Blanco!” We were just passing by too quickly. People only had time to turn and stare. I imagine we were quite the sight: two white guys riding weird-looking bicycles over big rocks in the middle of rural Haiti.

Soon we reached Route 102, and had a much easier time biking. We didn’t want to gain too much speed, though, because there were still plenty of sharp rocks in the road that could pop our tires. Somehow we made it all the way down to the main road with no bike issues, and continued biking up to the border.

BORDER CROSSING NUMBER TWO

“Ok, this time I ain’t paying a single dollar in bribes or helper fees,” I said to Matthew as we approached gate number one. “We already know where everything needs to be paid and what paperwork to get, so we should be able to do this all by ourselves.”

“Agreed, let’s save some money this time,” Matthew replied.

We got to the gate and a Haitian man asked for our passports and twenty dollars each. I refused and tried to bargain for five minutes, but he wouldn’t bargain. He even showed me an official ID card for the border, so I finally trusted him and gave him the money and passports. We made it through the gate with the official paperwork, then easily passed by gate number two (without needing to register our bikes again – that must have all been for show the first time).

At gate number three I went into the customs office, paid twenty dollars for each of us, and got both passports stamped. Finally we passed through the last gate, and saw Tommy waiting for us. He was surprised to see us so cut up from the bushwacking, but happy that we’d made it back. He walked us over to the immigration booth and took our passports for the final paperwork. In all, we each paid about $85 total in the form of fees and bribes to cross the border and return.

When Tommy returned we followed him on our bikes back to the police station in Jimani. Our car was exactly where we’d left it, unscathed and unbroken-into. We breathed two huge sighs of relief. We had successfully bagged the Pic la Selle and were finally back safe with all our belongings in the Dominican Republic. Twenty-four hours was all the time we’d needed on the ground in Haiti. We got in the car, turned up the victory Rock-n-Roll music, and started heading toward our next objective – Pico Duarte, the highest mountain in the Dominican Republic.

Email us (matthewg@alum.mit.edu, egilbert@alum.mit.edu) for the GPX/GPS track of our route up Pic La Selle.