Portugal

Montanha do Pico (7,731ft)

Matthew Gilbertson (Oct 8 2012) and Eric Gilbertson (Nov 9 2014)

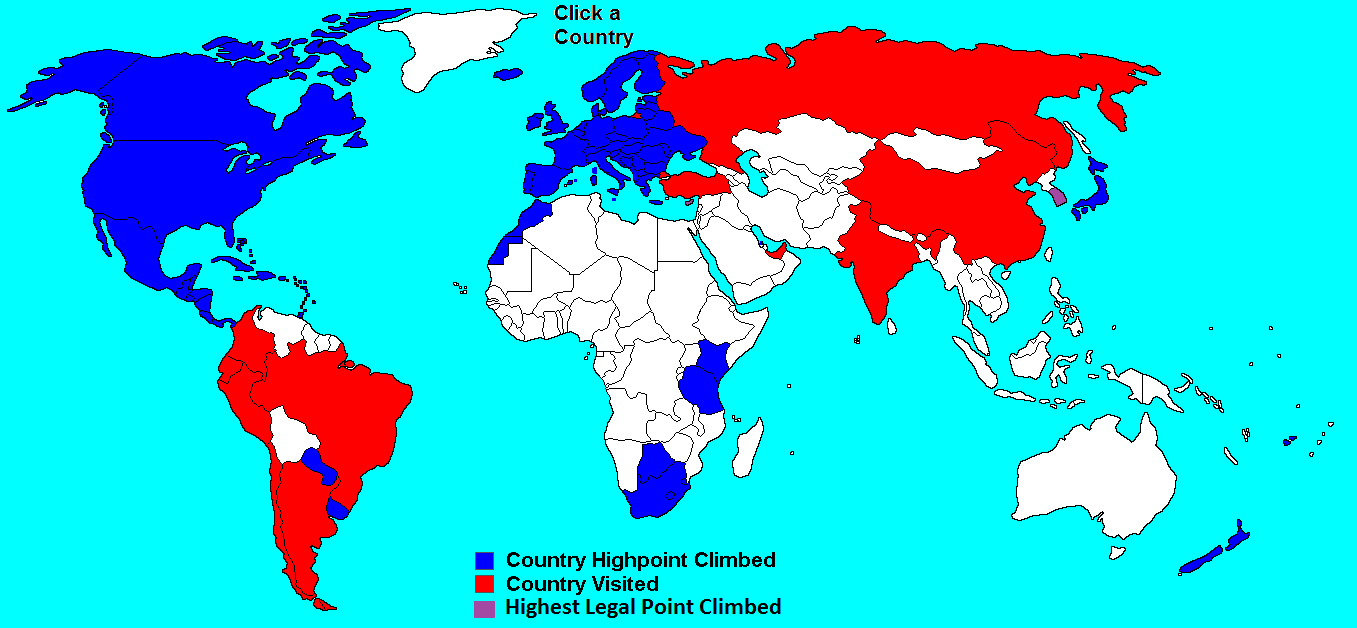

Montanha do Pico - Azores (7,731ft) - Highest Pt in Portugal

Pico Piquinho (7,713 ft) on Pico do Montanha - Azores

Highest Point in Portugal

October 4-7, 2012

Amanda Morris and Matthew Gilbertson

§ § § § § §

T-minus 10 minutes (somewhere on the slopes of Pico):

The ring could not get wet. So far, it had survived the long journey from Cambridge intact, protected from the elements by its cute little cardboard box and a Ziploc bag. It was still secret and still safe, buried deep inside my pack. But as I stopped to transfer the precious package into my pocket, in preparation for the big moment, the ferocious rain, driven by the hurricane-force winds of hurricane Nadine, threatened to tear it from my grasp and cast it into the Azorean Atlantic. Amanda probably wouldn’t like that.

A tremendous gust of wind ripped the breath from my lungs and blasted rain into my face like a fire hose, knocking me off balance. As I stopped to the squeeze the water out from beneath my eyelids, I began to understand some of the toils that poor Frodo had to undergo with his little ring on his own great quest.

§ § § § § §

T-minus 3 days (Cambridge, MA):

I was on a mission. It would involve danger. It would involve secrecy. It would require impeccable timing and an element of luck. And it began now.

The weather models showed a huge storm system converging on Massachusetts and the rest of New England, which didn’t bode well for our transatlantic flight that evening. The plan was to meet up with my girlfriend Amanda in Newark, before flying out to Lisbon together for the IROS robotics conference in southern Portugal later on that week. As a presenter at the conference, I already had a free ticket to Portugal; Amanda, meanwhile, had a week of vacation at the same time, so we decided to take full advantage of the situation with a mini-vacation together.

Of course, a big trip such as this wouldn’t be complete without a country high point. I spent some time researching the options and it looked like Portugal’s high point, Montanha do Pico, would be within the realm of possibilities. The intriguing thing about Pico is that it’s actually a tall volcano in a group of islands called the Azores, located about a thousand miles off the west coast of Portugal in the North Atlantic. Back in 1492, Christopher Columbus actually stopped in the Azores to stock up before heading west to the Bahamas. The Azores looked to be cool and green, and we figured that October would be the perfect month to go. That would turn out to be a miscalculation.

With the looming threat of flight cancellations, I deigned, against my dignity, to take a taxi to the airport. After forty-five minutes of gridlock that I probably could have beaten by walking, I made it to Logan and boarded an earlier flight with five minutes to spare. As it turned out, five minutes later and the trip would have had a vastly different outcome.

After rendezvousing with Amanda in Newark and enjoying some free food in the United Club lounge, we boarded our night flight to Lisbon. Seven hours later, we were in the capital of Portugal, ready for Phase 3 of the journey: getting to the Azores. And here’s where things got complicated.

T-minus 2 days (Lisbon airport, Portugal):

“Hmm, that’s weird,” I said to Amanda, “it looks like our flight to Horta is delayed by three hours.”

“I wonder what’s going on?” she said.

“I’ll go check.”

It’s not exactly straightforward to get to Pico. The plan was to fly from Lisbon to the island of Horta, then take an evening ferry to Pico Island, where we’d rent a car and drive to the trailhead. With any luck, we’d hike up at night, camp on the summit, and I’d ask Amanda the big question as the sun rose over the Atlantic. That was the plan.

“Uh, we’ve got a little problem here,” I said to Amanda. “Check this out, there’s actually a hurricane over the Azores right now. Hurricane… Nadine.”

“Great,” she said.

That wasn’t super-exciting news, considering that two of our four modes of transportation to Pico, plane and ferry, were very much weather-contingent. The other two modes of transportation, driving and hiking, would also be a bit trickier in hurricane conditions. I gasped when I clicked on the US National Hurricane Center’s advisory for Nadine. This was Hurricane Nadine’s twenty-second day as a storm, and the second time that it had struck the Azores. It would turn out to be the fourth longest-lived Atlantic tropical cyclone in history. I recalled vaguely, a few weeks ago, hearing about a storm passing through the Azores, but hadn’t paid any attention because I was certain it’d be gone by the time we arrived.

Hurricane Nadine was alive and well, and would you believe it, the center of the storm, the very eye itself, was centered where? Two miles southwest of the summit of Pico. The current weather map showed a monstrous spiral of storm rotating about Pico, probably the least favorable day for climbing the mountain in the past several years. The latest advisory said Nadine had maximum sustained winds of 90 mph, and was expected to weaken as it drifted slowly to the northeast. But would it vacate the islands in time?

“Well, we better get comfortable,” I said. “We might not be going to the Azores after all.”

We expected the flight to be canceled altogether, but the scheduled departure time held firm at 2pm. The original plan was to fly to Ponta Delgada first, the capital city of the Azores, then board a smaller flight that afternoon to Horta. But the Horta flight had already been canceled. As the hours ticked away we contemplated our options. The weather was fine here in Lisbon, but how could a plane land in a hurricane? Soon the gate agent made an announcement over the intercom.

“Announcement for all passengers traveling on SATA Flight 44012 to Ponta Delgada, the originally-scheduled 11:40am departure: your plane is here in Lisbon but the weather in Ponta Delgada is currently not safe to land. We’d really like to get you all to Ponta Delgada so here is what we’re going to do. The flight will take off at two o’clock and will land in Santa Maria [a tiny island in the Azores 100 miles south of Ponta Delgada, and 1,000 miles from Lisbon]. Based on the current conditions, the pilots think that they can land safely in Santa Maria. In Santa Maria, your pilots will wait for the conditions to improve in Ponta Delgada. The flight will take off from Santa Maria and attempt to land in Ponta Delgada. If the conditions are not favorable for landing in Ponta Delgada, the plane will turn around and return to Lisbon.”

Seriously? That was the plan? “We’ll attempt to land”? I mean, you’ve got to give them credit for their gutsiness and determination, but I think that any American airline would just say, “sorry, flight’s canceled, come back tomorrow.”

“Wow, cool!” I said to Amanda. “It’ll be just like the ‘Hurricane Hunters’ – we’ll get to fly right into the eye of the storm!”

She was not quite as amused. “Well we might make it to the Azores,” she said, “but we might be stuck in Santa Maria or Pont Delgada for the next few days – there might not be any flights to Horta.”

True. The chances for getting to the summit of Pico were dwindling and we began to discuss how we could salvage our rapidly-crumbling plans. São Miguel (Ponta Delgada’s Island) and Santa Maria both looked cool, but they were so small that the opportunities for two days of adventure appeared limited. What if we just stayed in Lisbon, rented a car, and drove around Spain and Portugal instead? As cool as that sounded, we agreed that we were still intrigued with the Azores, and decided to give this flight a try. If we made it to the Azores, great, if we had to return to Lisbon, that’d be fine too, we’d still have a good time.

T-minus 45 hours (Lisbon):

At 2pm we were up. A shuttle bus took us to our plane, an A320. “Wow, that’s a lot bigger than I expected,” I said. We filed in and sat down next to a Canadian woman. As we would learn in painful detail over the next few hours, the woman was part of a large hundred-person or so Canadian tour group that was headed to Ponta Delgada (PD). They had taken off from Toronto the previous evening and actually had a direct flight to PD. After making two unsuccessful attempts to land at the PD airport in spite of the raging hurricane, including one pass in which they could see the runway, their direct flight to PD became a direct flight to Lisbon. We were getting the sense that there were a few daredevils among the SATA flight crew.

This would be the Canadian group’s second try to get to PD and they were getting a little tense. “We better make it to Ponta Delgada,” the woman said, “or I’m gonna demand my money back.” So that explains one reason for the larger plane and thus the delay: perhaps they needed a bigger plane to carry an extra hundred people, not to mention the superior stability of a larger plane when landing in strong winds.

Three hours later, buffeted by gusty winds, the plane jerked up and down as we began our final descent into Santa Maria. There wasn’t much in the way of scenery except the dark gray storm clouds of Nadine above the roiling, violent, white-capped North Atlantic.

“Ladies and gentlemen, in preparation for landing, please ensure that your seatbelt is fastened securely about your waist,” the captain said, “it’s going to get a little bumpy here.” With a few jerks the pilots expertly brought the plane down at the Vila do Porto Airport in Santa Maria and the cabin erupted with applause. We were closer to our destination, but still had a ways to go.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” the pilot said, “we just got a report from Ponta Delgada and the weather conditions have improved. But it’s still not safe to land there. For now, we will wait here, monitor the conditions, and give you an update in about one hour.”

“Oh, come on, you’ve got to be kidding me,” the Canadian woman said. “We’re going right back to Lisbon.” Tension began to increase until it became almost palpable. After half an hour, as we sat in our seats amid the torrential downpour and ferocious wind bearing down outside, the tension had reached a boiling point. It felt like a mutiny was about to occur.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” the flight attendant said, “some of you have expressed interest in disembarking here in Santa Maria. We’re going to open the door in a moment and give you the option to do that. But keep in mind, I’ve just been informed that all of the hotels on the island are booked tonight. This is a small island that is not able accommodate many people. If you choose to disembark here, you will be on your own, and you will be responsible for your return flight.”

“All right, that’s it,” the woman said to me, “we’re getting off here. I’ve had enough of this nonsense.” She grabbed her bags and exited the plane with a dozen or so of her compatriots. They shielded their faces with luggage as they staggered through puddles and rain squalls to the terminal, 100 feet away.

Amanda and I had to make our own decision. Fortunately the Wi-Fi signal from the terminal was strong enough that we could access the internet from the comfort of our seats. Latest forecast was for more of the same: winds and rain gradually decreasing over the next few days as the storm slowly departed. All flights to Horta had been canceled. “Well it looks like Pico’s out of the question at this point,” I said to Amanda. “Two options: get out here in Santa Maria or try for Ponta Delgada.”

“Well there’s not too much to do here in Santa Maria,” she said. “It’s pretty but the island is, what, five miles wide? We do have the tent, but do you think it’ll stand up to this kind of wind? I’d say we should stay on the flight, hope it can’t land in Ponta Delgada, and hopefully we’ll continue on to Lisbon for a different kind of adventure. No matter what, we’re probably not going to be able to make it to Pico.”

Agreed. “Yeah, hopefully we can’t land in PD. At this point, there’s no chance we’ll be able to get to Pico, and there’s more options in Lisbon. So we stay on this flight.”

T-minus 42 hours (Santa Maria runway, Azores):

A half-hour later the intercom crackled to life. “Ladies and gentlemen,” the pilot said, “the conditions at Ponta Delgada have not improved much over the past hour. But we’re going to give it a try. If we’re unable to land then we’ll continue to Lisbon. Flight attendants, please prepare the cabin for departure.”

We buckled up and launched back into the storm. Because of the short distance to PD, we had to fly lower, dodging storm clouds, and as a result the flight was a lot bumpier. A half hour later, the island of São Miguel emerged through the fog. As the wheels approached the asphalt, the pilots made a few final corrections, and everyone held their breath. We hit the ground softly and the thrust reversers deployed, spraying water everywhere with an enormous roar. The cabin erupted in applause and, for better or for worse, we were now in Ponta Delgada.

People began to disembark, and we were at yet another crossroads. Here we were, finally in the Azores! But we weren’t exactly celebrating. We could disembark here, but then what would happen tomorrow? We probably still couldn’t get to Pico, we’d be hanging out in Ponta Delgada for the next few days, and who knows what after that? Maybe the storm will stick around, ground all flights, and we’ll have to miss the conference. That would not be good.

“Let’s just stay on the flight,” Amanda said, “we know this is going to Lisbon, this might be our last chance.”

“But they want us to get off here,” I answered, “let’s just get out, then go the ticket counter, and tell them we want to re-board the flight to Lisbon.” Soon the flight attendant came to herd everyone out, and we had no option but to disembark.

We hurried out of the plane, entered the terminal, and dashed to the ticket counter, hoping that we could secure two seats on the flight before it departed. Ten agonizing minutes of waiting later, we were at the front of the line. During the next sixty seconds our fate would be decided.

“Hello, we just got off the flight from Santa Maria and were wondering if…” I started.

“What are your names, please?” she asked. We told her. “Amanda Morris and Matthew Gilbertson? Oh yes, we’ve been expecting you. The flight to Horta ended up being canceled today anyhow, so you didn’t miss it; we’ve scheduled a new flight to Horta that leaves at 9am tomorrow morning. As for tonight, we’ve booked you at the Hotel VIP Executive in downtown Ponta Delgada. There is free buffet dinner and buffet breakfast. And we’ve arranged for a free taxi to take you to and from the hotel.”

At that moment, SATA became my new favorite airline. Despite a raging hurricane, they had managed to bring us all the way to the Azores, had scheduled a make-up flight for us in the morning, and booked us at the fanciest hotel in town. Free buffet breakfast and dinner? Icing on the cake. I mean, I like camping in a tent and being a cheapskate, but there’s no loss of honor when you stay in the fanciest hotel for free, with unlimited food, and when it’s hurricane-ing outside. I thought briefly of the poor Canadian woman, who was probably sleeping on some benches in the Santa Maria Airport this evening, but it was only a fleeting thought.

“Thank you ma’am!” Amanda said, “Obrigado!”

“You’re welcome. And here are your taxi vouchers; the taxi is waiting outside to take you to your hotel. Enjoy your stay here in the Azores.”

Somehow, we had played our cards just right. In any respectable adventure, there’s always that one low point at which, battered by one setback after another, you think that there’s no way things could possibly work out favorably. But then, there’s a glimmer of hope, that turn-around moment. And then things finally begin to rebound. We had just passed through that point. Pico still looked out of the question, but things were finally falling favorably into place.

T-minus 41 hours (Ponta Delgada, Azores):

Fifteen minutes later the taxi dropped us off at our hotel, and it was no wonder why it was called the VIP Executive. There probably wasn’t a nicer or larger hotel within a thousand-mile radius. We were itching to do some exploring while it was still light out, so we dropped our stuff and started running. The vague plan was to run down to the Ponta Delgada waterfront and check out the waves created by the hurricane. “Don’t you think we should take a map?” Amanda said. “No, we’ll figure it out,” I reassured.

We had spent the past day and a half cooped up in airports and airplanes so it felt good to finally stretch our legs on Azorean soil. We ran down old cobblestone streets, marveling at the workmanship. The roads were comprised of black cobblestone, but on the sidewalks were cool white cobblestone mosaics of fish, squid, and other sea creatures. The buildings looked like they hadn’t changed too much since Columbus came through.

Down at the waterfront, we climbed up on a 30ft seawall and watched the giant waves crash into the shore. The waves were impressive, but we could tell that the indomitable seawall was not impressed. This area is accustomed to hurricanes, and a little Category 1 weakling like Nadine was hardly enough to wet the paint on the sea wall.

On the way back I insisted on taking a scenic route through the old neighborhoods. I had hoped to make a shortcut back to our hotel but, well, my sense of direction wasn’t perfect. “Um, I think we go this way,” I said to Amanda. In the end, we somehow ended up back where we had started. “Well, at least we got a good tour of the city,” Amanda said, with infinite patience. We ran back to the hotel, eager to check out the buffet dinner.

The dinner did not disappoint. With just about any food you could ask for, it was the kind of dinner where you’re like, “man, this food is awesome and unlimited, I wish I could just eat up now and not have to eat again this week.” Alas, it doesn’t quite work like that, but we certainly did get our money’s worth – actually SATA’s money’s worth – out of the feast.

Our only qualm with the hotel was that you had to pay five Euros for a shower cap in order to use the pool. Some kind of local superstition about uncovered hair in the pool. We figured our two hour run through the rain basically counted as a swim, and it had been free too. Five Euros was just plain ridiculous.

T-minus 27 hours (Ponta Delgada):

In the morning I went for a quick run through the torrential rain to get some photos of a cool stone fortress, and then we were back in the taxi, headed to the airport for our 9am flight to Horta. The weather hadn’t changed – in fact, it was now raining harder – but miraculously the flight was still on schedule. I suppose the Azorean pilots are just accustomed to a little wind and rain. “Maybe we’ll make it to Pico after all,” Amanda said.

After a smooth flight and a quick, scheduled stop in Terceira, we took off again for Horta. As we climbed, Amanda spotted a huge, towering mountain in the distance. “That’s Pico, Matthew!” she said. A dark, gigantic mountain loomed on the horizon. Amazingly, over 90% of the mountain was visible – just the very top was poking into the clouds. I perked up. “Wow, the weather looks good too, maybe we’ll actually make it to the top!”

My mind was already racing. Wow, with weather like this, I thought, the hike will be a piece of cake, so much for this Hurricane Nadine, ha. We’ll camp on the summit tonight, I’ll ask the big question in the morning, then what’ll we do the rest of the day tomorrow? We’ll have plenty of extra time. Oh, if had only been that simple.

Bursting with excitement, we landed at Horta, a short airstrip guarded on one side by a sixty-foot sea cliff. The rain had stopped, temps were near 70F, the sun was peeking out, and it finally began to feel like the Portuguese weather we had expected. We had arrived in Horta almost one day later than planned, but there was enough buffer in our schedule that the delay hadn’t set us back much.

The taxi driver took us straight to the ferry terminal, where we’d add another mode of transportation to our trip’s resume with the ferry to Madalena, on the Island of Pico. The spacious ferry terminal resembled a giant bunker – it was probably designed to handle any storm the Atlantic could dish out. Fortunately, the Transmaçor Ferry ran frequently, with a dozen crossings per day. We didn’t have to wait long before hopping onto the Cruzeiro do Canal for the half-hour ride to Madalena. The sea was mercifully calm and we stood on the top deck to admire the view. The wind had picked up and Pico was fully enshrouded in clouds, but we figured they’d burn off in the morning. Little did we know that Nadine was still very much present, and the past few hours of decent weather would turn out to be just a mere lull in the storm – basically the eye of the hurricane.

As we cruised to Pico, Amanda noticed a professionally-dressed woman sitting in the front row of seats. She was accompanied by two well-dressed guys, who seemed to be her body guards. “Hey, Matthew, that’s the woman who’s running for election, Berta Cabral! I’ve seen her photo on the billboards.” Amanda’s got an impeccable memory of faces so I didn’t doubt it. “I’ll go sit next to her,” she said. She must have been canvassing for more votes on Pico. Man, I thought, Azorean people are tough; they’re not afraid to travel and do business during hurricanes. (Editor’s note: it was indeed Berta Cabral, but unfortunately she would lose the election the following week.)

T-minus 21 hours (Madalena, Azores):

We disembarked the ferry in Madalena and made a beeline for the Ilha Verde car rental. It took some time to round up the owner, but fifteen minutes later he arrived and we began to chat.

“Welcome to Pico,” he said, “how long are you guys here for?”

“Just one full day,” I answered, “we’re going to climb Pico tonight or tomorrow morning.”

“Oh, Pico, very good,” he said, “it’s a nice hike but the weather is supposed to be very bad for the next few days. Lots of wind and rain.”

We were a bit dismayed with that update but I didn’t take it too seriously. “I guess we’ll just give it a try,” I said.

He showed us to our rental car. “Well this is the last car that we have, all the other ones are checked out.”

I peeked into the window and immediately noticed that it was a stick-shift. But that wasn’t a big deal. Online, I had reserved an automatic because it was a few dollars cheaper, but had secretly wanted a manual. In preparation for this trip, and for future car rentals in places without automatics, Eric and I had rented a stick-shift in Cambridge a month earlier and had driven it up to Maine for some hiking. There was a lot of gear grinding, engine revving, sputtering, and some words that will not be repeated here, but in the end it was a good learning experience.

So, with three full days of manual-driving practice under my belt, I plopped confidently into the driver’s seat of our little black Renault Clio, and we were on our way. Fortunately Amanda did the navigating and brought us to a nice little grocery store on the outskirts of town. We were delighted to discover that the food prices here in Madalena were actually comparable to those in the US. There was no tourist-gouging here on the Island of Pico.

We departed the village of Madalena and headed into the foothills. As we climbed, the fog grew denser, and we could feel the wind shake the car. We wound upwards through lush cow pastures and pumice stone fences that had probably been constructed hundreds of years ago. Amanda expertly navigated us through the network of farm roads and finally a large building emerged from the fog. It was the visitor’s center. After six flights, two taxis, a ferry, and ten miles of driving, we were finally at the trailhead for Pico. We still had the entire mountain left to climb, but it felt like we had already won. I mean, compared with all the other obstacles we’d overcome so far just to get to the trailhead, how hard can two miles of hiking and 3,600 ft of climbing be?

It was getting late but still I didn’t want to let go of my plan to camp on the summit. How cool would it be to camp on the top and ask the big question at sunrise? The hurricane’s leaving so it’ll clear up overnight, right? Hey, maybe there’ll even be stars. As we ate our dinner in the car at the visitor’s center parking lot and discussed the plan, we could feel the car rock back and forth, buffeted by the ferocious winds. The fog grew denser, the rain picked up, and we came to the reluctant conclusion that the storm was actually intensifying. “Well, I guess we can go up in the morning,” I said to Amanda, “now’s probably not a great time to be on the mountain.” So, with a sigh of relief from both of us, we relaxed into our seats as the storm raged outside.

T-minus 15 hours (Pico do Montanha trailhead):

“Well I think I’m going to sleep outside in the tent tonight,” I told Amanda, “I can never get to sleep in cars.”

“Are you kidding? There’s no way you’re going to get any sleep outside in that storm,” she answered. “That tent is going to be flapping around all night.”

“I think it’ll be OK, I’ll just stake it down really well.”

I grabbed the tent, opened the door, and took the plunge into the tempest.

Rule #47 in camping: when you buy a new tent, practice setting it up indoors first. Don’t try to figure out how to set up the tent for the first time during a hurricane. Well that’s one rule that I won’t be breaking again anytime soon. As I unrolled the brand new tent, trying to figure out which side was up and which was down, the wind nearly ripped it from my grasp. I was like a flagpole and my tent was the flag, flapping in the wind.

Imagine that you’re in an airplane, flying through a hurricane. Then imagine that, with a tent in your hand, you open the cabin door and make you way onto the wing of the airplane. You then proceed to pitch your tent on wing itself. Well, that’s just about how it felt trying to set up our tent in the parking lot. The tent would be flapping all over the place, plastered to my face by the wind and rain. I’d finally locate a corner of the tent and attempt to stake it to the ground. But the gravel parking lot was so hard-packed that the aluminum stakes preferred to bend rather than penetrate the ground, and the tent would go sailing back into the air.

Amanda came out to help and eventually we managed to pin the tent down to the ground, assemble the poles, and threw on the rainfly. We hopped back inside the car for a breather, completely soaked and out of breath.

“Do you really think it’s worth it?” Amanda asked.

“No, you’re definitely right,” I said, “there’s no way I’d get any sleep tonight in there – the wind’s so strong it’d probably snap the poles. Let’s take that thing down, I think I’ll sleep in the car tonight instead.” We broke the tent down and stuffed the sopping wet pile of nylon into the stuff sack. It would be more effective as a pillow tonight than as a shelter.

It wasn’t exactly the most comfortable sleep in the back of the tiny little Renault, but with the wind and rain lashing the car all night, it was certainly cozier to have steel and glass between us and the wind instead of a few hundred microns of synthetic fabric.

T-minus 3 hours, 7am (Pico Trailhead):

Dawn broke and, with a heavy heart, we came to the conclusion that the weather had actually not improved. In fact, it had probably worsened overnight. “Well, at least it’s brighter now than it was last night,” I said. “Psychologically, at least, it feels nicer.”

“Do you really think it’s a good idea to go up in this weather?” Amanda asked.

“Well the weather’s not great, but maybe we could at least give it a try, maybe just go up a little ways? Looks like it’s about 1.8 miles of hiking and 3,600 ft of climbing from here to the summit, so a little less than Mt Washington.”

“How long do you think that’ll take?”

“Well Summitpost says between 6-7 hours roundtrip, but we’re usually a little faster than that.”

While we packed up inside the car and discussed our options, another car drove up and two people walked into the visitor’s center. We guessed that they were probably rangers and would be able to give us the scoop on Pico. “Let’s go talk to them and see if they have any more info,” I suggested. I was expecting some pushback when we announced our plans to the ranger, but was not prepared for the extent of the dissuasion that we would receive.

We walked inside and a uniformed woman greeted us. “Good morning,” she said.

“Good morning,” we answered. “Nice day to climb Pico, huh?” I joked.

“Yeah right,” she smiled, “this is one of the worst days of the year to climb the mountain.”

“How far is it to the top?” Amanda asked. By that point, I think Amanda had already decided that she wouldn’t be climbing the mountain today, but she wanted to gather information for me.

The ranger stopped smiling. “It’s about three kilometers to the top and about 1500 meters of climbing. Don’t tell me you want to climb it today.”

“Well we’d at least like to give it a try,” I said.

“Do you realize how bad the weather is today? We’re in the middle of a hurricane. Do you know how much stronger the wind will be at the top? There are many guides here on the island who have climbed the mountains hundreds of times, and I can tell you, they wouldn’t even climb it today, it’s just too dangerous.”

“I know the weather is bad, but we’d hike up a little ways, and if it is too dangerous to continue then we’ll turn around.”

“The problem is not the wind and the rain but the visibility. The trail is marked, there are forty-five numbered posts along the trail from here to the crater rim, and they are spaced closer together near the top. But today I don’t think you’d be able to see from one post to the other. If you do turn around, what if you can’t find the trail? It would be very easy to get lost today.”

“Well, I do have a GPS,” I said, showing it to her. “And I have someone else’s GPS track on it that I can follow to the top.”

She rolled her eyes and could tell that I wasn’t going to budge. “Well, if you insist on going,” she said, “even though I’m telling you that it’s extremely dangerous, you are first required to watch a ten minute video downstairs. I’m not able to tell you that you cannot climb. I can only present all the information that you need to make your own decision.”

“OK, we would like to watch it.”

“Follow me.”

We sat down in the cozy auditorium in the basement and watched as the video discussed the climb and showed videos of a tantalizingly cloudless, windless summit. Oh, if only we could have come a few days earlier or a few days later, I thought, and things would have been so much simpler. As the video concluded, she asked, “so, what have you all decided?”

“I think we’d like to talk about it a little bit,” I said. Amanda and I stepped outside for a powwow. By now I could tell that Amanda was not interested in climbing to the top. But she could tell that I had not given up. I wanted to climb, but I felt bad suggesting that she stay at the bottom while I climbed to the top - I didn’t want her to think I was abandoning her. At the same time, I think she felt bad letting me go by myself – she didn’t want me to think she was abandoning me. We soon came to the conclusion that the most mutually agreeable solution would be for me to climb by myself. Amanda would get to hang out in the nice, warm, dry visitor’s center while Matthew got lashed by the cold wind and rain. It sounded like a fair compromise to me.

Meanwhile, my secret plan to propose to her on the summit was rapidly crumbling.

“What do you think?” Amanda asked.

“It’s about like Mt Washington foggy day,” I said. “It’s pretty windy, but I’d still like to give it a try. I think I would really regret it if I turned around here and didn’t even take one step on the trail. I’ll go up and turn around if it gets too bad, I’ll be safe.”

Amanda accepted that, and we walked back inside the visitor’s center to announce our plans to the ranger.

“We’ve talked about it, and I’ve decided that I would still like to give it a try. Amanda will stay here and I’ll hike it by myself.”

It was a solemn moment. The ranger rolled her eyes and breathed deeply, clearly disappointed with the decision. “OK, if you are going to climb it today, I am not going to be surprised if you need to be rescued. Do you know how much a rescue costs? It’s about one-thousand Euros. And with weather like this, the rescue team might not even come to get you. Many people have gotten hurt in weather much better than this and have needed to be rescued. You will have to pay the entire cost of the rescue. I am going to give you our phone number, so you can call us if you have problems.” She gave me her colleague’s cell phone number and I called it just to make sure it worked.

“Inside the crater there is no cell phone coverage, so if you get hurt in the crater you will be on your own. As I said before, I cannot stop you from climbing the mountain, but I can present all the information that you need to know. Do you agree that I’ve talked with you about all of the dangers that you’ll be facing today?”

“Yes, I agree, you’ve told me about all of the dangers. But I still think it’s an acceptable level of risk for me. I will be safe, and I will turn around if the conditions get too bad.”

“OK, then I think you will be turning around very soon. It’s usually 7-8 hours to the top, but if you make it I would expect about six hours for you.”

“OK, then if I make it to the summit I’ll try to call from there. Otherwise, I will try to call in three hours. But if you don’t hear from me then, don’t send a rescue party.” I was starting to get more worried about her jumping the gun and sending up a rescue party than I was about the actual dangers of the mountain. I’d never encountered so much pushback from a ranger about climbing a mountain. She spent another ten minutes trying her best to dissuade me.

“Why don’t you climb up tomorrow?” she asked. “The weather is going to be much nicer.”

“Unfortunately, we’re leaving tomorrow,” I said.

Over the course of the past half an hour, the ranger had tried every tactic from every angle to dissuade me from climbing. But she was just doing her job. From our perspective, we had spent so much effort to get from the States all the way over here to Pico; despite the hurricane, we had managed to make it to the trailhead itself. To make all that effort worth it, we needed to at least give Pico a try, right? Meanwhile, from the ranger’s perspective, here were two Americans, who had made a long journey, but had given themselves just one day to climb the mountain. People have gotten hurt on the mountain in fine weather, even those who know the mountain. How can someone unfamiliar with the mountain just show up on the worst day of weather in the past year, and expect to safely make it to the top, alone?

But Amanda respected my decision. “Be careful,” she said, “take my poncho.”

“I will. I’ll be back in a few hours,” I said.

And with that, I bid farewell, opened the doors, and took the plunge into the storm.

T-minus 2.5 hrs (Pico trail):

At that point, the weather wasn’t all that bad. The wind was gusty but the rain had paused and the fog had thinned slightly. I started out running, hoping for a rapid ascent to minimize the ranger’s chances of calling an unnecessary rescue party. I passed the first wooden marker and stopped to delayer. One marker down, forty-four to go. Hey, this isn’t so bad, I said to myself. Just like climbing Mt Washington.

I kept running and soon the fog thickened up, the wind stiffened, and a cold drizzle began. I definitely couldn’t see one from one marker to the other, but the trail through the bushes was evident enough so it wasn’t a big deal. Higher up though, the bushes disappeared and things began to get dicey. I kept climbing and the trail fizzled out. Oops, I had just taken the wrong path – I was now in a creek bed. I backtracked to the last marker post and found the correct path. OK, Matthew, time to concentrate, I said to myself. Take your time and be sure of the trail, you’re on your own here.

As the vegetation disappeared and the terrain turned to volcanic rocks, the trail became fainter and fainter. Normally, you can locate a trail by looking for an absence of vegetation or lack of lichen on the rocks. But in a sterile environment like this, it became tricky. Post #32, post #33, … I was getting higher but the conditions were rapidly deteriorating. Gusts would occasionally knock me off balance, and I’d often need to brace myself against the rocks to keep from falling over.

How fast was the wind blowing? Like any fish story, it’s easy to exaggerate windspeed (“man, it must have been blowing at 150mph!”), but I’ve heard that one rule of thumb to is to take your weight in pounds and divide that by two. That gives you the wind gust speed, in mph, that would knock you over. By that reasoning, I’d estimate the gusts were in the 80 mph range. Seriously!

But it wasn’t just the wind, it was also the rain, cold, and fog that really made things sketchy. A huge gust of wind would hurl the windborne rain droplets against my face; it felt like someone had just thrown gravel at me. Sometimes, during particularly epic gusts, the rain would get driven underneath my eyelids and I’d need to squeeze and massage the moisture out with my fingertips. At that point, I wish I had brought my swimming goggles – I actually think that they would have helped. To make things worse, the temperature dropped as I climbed, and I was rapidly losing feeling in my hands. A quick check of my thermometer revealed temps in the lower 40Fs. I tucked my hands underneath my armpits and kept running.

Unfortunately, after many years of abuse, my rain jacket was no longer waterproof. By about marker post #35, all of my layers were completely saturated. With water directly against my skin, I was now wearing an extremely inefficient wetsuit. To stay warm, I absolutely had to keep running. There would be no “stopping for lunch” this morning.

I had been following a little gulley up for most of the way so far, but suddenly the trail turned and began to traverse the side of the mountain. I crested a short hill and felt like I had just stepped against a wall. The roaring wind repelled me back. I ducked and tried again and managed to pierce through the invisible barrier, finding refuge on the other side.

Finally, after about an hour of climbing, I reached the magical marker post #45 and was greeted with the flatness of the summit crater. Um, great, now what? I asked myself. I descended a short ledge into an area of relative shelter and the summit plateau spread out before me, blending into the fog. No higher ground was visible, but I knew that I wasn’t on the summit just yet. Somewhere, hiding in the fog like some tall ship, was the final summit hill known as Pico Piquinho, which rises 210 ft from the floor of the crater. But there was no trace of any trail whatsoever, just rocks all over the place.

Well, time to consult the GPS, I thought to myself. At that point, my fingers were almost completely useless; I could barely pass the thumb-to-pinky dexterity test. Before my fingers became completely numb, I decided that I should scarf down as much food as possible and perform all the tasks that required fingers. I chugged some water, and bit open a Gu packet and some granola bars, forcing them down. I fired up the GPS and stuffed it into my pocket.

Shivering, I consulted my thermometer. 39F. Brrr, time to get moving. In an effort to try to trap some precious body heat, I removed a small white trashbag from my pack, ripped a few holes in it, and slipped it on as a vest. Then I slipped on my saturated rain jacket and donned another, larger trashbag that fit around my upper body and pack. It was no use trying to keep things dry – there wasn’t a dry thread remaining on my body – it was now a matter of blocking the wind, and trying to warm up my wet clothes.

After consulting the GPS to point myself in the right direction, I stuffed my hands into my pockets and started sprinting across the talus, in an effort to generate some body heat. To any observer, it would have been a bizarre sight: a giant black trashbag with legs and a head dashing through the raging storm. But the only witnesses were the rocks and the raindrops.

Once in a while I would pass a small cairn, but they were so faint and sparse that they were not useful for navigation, only for confirming that I was still on the correct path. After a few minutes, a large dark form loomed in front of me. It was Piquinho, the final 200 ft of climbing. I was thankful for more climbing, because it meant more exertion and thus more body heat generation. The slope steepened dramatically, and I was forced to extricate my hands from the comfortable shelter of my pockets in order to help me keep my balance on the soft, steep screefield. It was hard work, but welcome hard work because it warmed me up.

At about the moment that the feeling returned to my hands, the climbing ended and, at 7,713 ft, I was on the roof of Portugal. “YEAH!” I yelled at the top of my lungs. There aren’t too many places where you can yell at the top of your lungs without attracting attention to yourself. Underwater is one place. And the top of Pico do Montanha during a hurricane is another such place.

On the summit, there was a small concrete pad and a short structure with rebar sticking out of it. But as I walked around a boulder, reaching for the structure, an epic gust of wind pushed me back. I felt like I was trying to walk upstream through a river. The wind was so saturated with water that it almost seemed like it was the momentum of the rain that was knocking me back. I leaned into the wind and pushed through, finally making it to the summit structure. I was the highest person in Portugal.

T-minus 1 hour (Pico summit):

At that moment, it occurred to me that Amanda had made an excellent decision not to come to the top. I was certain that she could have made it; I was also just as certain that she would not have enjoyed it. It was time to start thinking about my Plan B with the ring. It certainly would have been interesting to propose to her here on the summit, but it probably wouldn’t have been a great idea because the ring would have blown away and I couldn’t have heard her answer anyway. Well, if I can’t propose to her on the summit of Pico, I thought, I’ll at least do it as high up on the mountain as I can. So I decided that, at this point, best location would be the trailhead.

The wind was ferocious and I knew that I only had a few more minutes of warmth before I would start shivering again, so I quickly whipped out my Gorillapod, screwed it onto my camera, and snapped one precious self-portrait. There was no time to check the photo quality or remove the tripod, so I just stuffed it into my pocket and began my descent. It had taken almost three days of travel for just one minute on the summit, but it had been totally worth it.

I checked my watch. 1h30m up. If all went well, I realized that I would probably get back down to the bottom before they even thought I was half way. I wondered, what is that ranger thinking now? She’s probably worried because I kept going and didn’t turn around immediately. What’s Amanda thinking? Well, she’s probably less worried because she knows I have good judgment and will stay safe. Man, she’s probably sitting in a nice warm, comfortable chair, in that nice warm visitor’s center, reading a book... That sounds awfully good right about now.

I carefully picked my way over the boulders and did some glissading down the scree field. OK, Matthew, you’ve made it to the top, I said to myself, you’ve gotten your prize. Just don’t blow it on the way down. I was shivering, soaked, and ready for a breather, but I knew I had to keep moving in order to maintain my body heat.

In Wilderness First Aid class, I learned that you can keep track of a patient’s level of pain by asking them “on a scale of one to ten, with ten being the worst, how would you rate your current level of pain?” It helps to quantify pain, but it’s tough to really think of what a ten would actually be. For me, on that day near the summit of Mount Pico, I think I set my new definition for “ten” on my “discomfort scale.” I wasn’t exactly in pain, it was more of a “discomfort”; perhaps, more accurately, I’d call it a solid ten on the “desire to get back to the trailhead” scale.

I made it back to the crater rim, passing my old friend, Post #45, and continued to descend. Just forty-four more to go. As I made my way down and the weather gradually became less terrible (I wouldn’t go so far as to say it became “better”), my mind was able to start thinking about other things besides just survival.

T-minus 15 minutes (somewhere on Pico):

I had accomplished one major objective on the trip, climbing to the summit of Pico, but it wasn’t actually my main objective. The main objective wouldn’t require running, hiking, or any particular amount of physical exertion, it would instead require getting down on one knee and offering a ring.

Did Amanda suspect anything? I wondered. As I neared the finish line for Pico, I stopped in a small cave for a moment to transfer the precious cargo from my pack to my pocket in order to make it more easily accessible. I hopped carefully from one boulder to the other, jumping over the creeks and streams that seemed to have popped up out of nowhere since I had started up. Finally, after an elapsed trip time of 2h17m, the lights of the visitor’s center came into view.

I triumphantly tip-toed down the concrete stairway, snapped a quick photo and opened the door. Amanda came running over to meet me and the ranger lady meanwhile turned her head to glare at me. “I made it to the top,” I announced, showing off the summit photo.

“Yes that’s the top,” the ranger said as she examined the photo, “but what you did was very dangerous.” Now, I wasn’t exactly expecting any congratulations from the ranger, but I was at least hoping that she would have a positive word to say now that I had returned safely.

I stripped off my tattered trash bags and Amanda gave me some hot chocolate. “It only took two hours, seventeen minutes,” I said to Amanda.

“Wow, that’s impressive, I didn’t even expect you for another few hours,” Amanda answered.

“Well the record is one and a half hours, set by two German ladies,” the ranger interjected, after she overheard my comment. “You should have seen the two ladies, they’re in very good shape.”

“Well they probably weren’t climbing it during a hurricane,” I whispered to Amanda.

After a few final admonitions from the ranger, we bid her farewell and stepped into the fog. We hopped in the car and I said to Amanda “hey, let’s drive over there a few hundred feet to that sign and take one last picture.”

“OK,” Amanda said, oblivious to what was coming.

“Stand over there, I’ll put the camera on time-delay mode,” I said to her. I attached the camera to my Gorillapod and mounted it to the handle of the car door. She didn’t know it, but I hadn’t set it up to take a photo, I had pressed the movie button instead. The video was now rolling. “OK, now look at the camera,” I said.

The wind was roaring and through the dense fog, you could barely see the car, even though it was just a few dozen feet away. Amanda’s hair blew into her face, obstructing her vision. Now is my chance, I thought. I pulled the little box from my pocket, knelt down, opened it up, and presented it to her. “Will you marry me?” I asked.

Amanda’s initial expression of absolute surprise quickly turned into a nice big smile. “Of course!” she said.

Mission accomplished.

§ § § § § §

The trip report should really end here. I had just completed the primary objective of the adventure. I was no longer the ring bearer. And to add some icing to the cake, I had summitted Pico and had returned safely. Amanda and I decided to celebrate by taking a little victory lap around Pico Island.

We pulled away from the now-hallowed ground of the Montanha do Pico trailhead parking lot. Luckily the excitement had occurred far enough away from the visitor’s center that the ranger hadn’t seen us. If she had, I can only imagine what she would have been thinking: a couple of Americans show up in the middle of a hurricane, some guy runs up to the summit, returns soaking wet, and then proposes to a girl at the trailhead? What kind of a bizarre ritual is this?

As we descended the steep road we dodged a few abominable mountain cows. “Don’t you guys know that it’s bad to hang out on the road in the dense fog?” I wanted to yell at them. But they probably wouldn’t have understood our English anyhow. A bit farther down, we pulled off onto a side road so Amanda could get some practice driving a manual. As she practiced stopping and starting, the ferocious winds of the hurricane bore down on the car and nearly pushed us across the parking lot.

“I think I’ll stick to navigating and you can do the driving!” she said.

“All right, sounds good to me.”

Finally we made it back down to the coast at Prainha de Cima and the fog began to thin. We headed around to the eastern end of the island then looped back on the EN-1. We stopped at the village of Ribeiras, a small fishing town perched atop the rocky coast. It looked like many of the boats had been taken out of the water in preparation for the big storm. We spotted a swimming pool that was situated right on the shoreline and had gotten swamped by the big waves. “Not a great day for a swim!” Amanda said.

As we looped back towards Madalena, we realized that we would have plenty of time to spare before the 5:15pm ferry to Horta so we decided to check out the beach. After passing through some old volcanic-rock stone fences we spotted a parking lot on the shore and a sign that read “praia não vigiada” [no-lifeguard beach]. “It doesn’t look very inviting does it?” Amanda joked. The beach was completely invisible, hidden beneath the crashing, foaming, ten-foot waves.

At last the clouds parted and we could finally enjoy our first few rays of direct Azorean sunlight. The sunshine quickly stirred up our primal hiker instincts to dry out gear, so we tossed our wet items on the warm ground for some free drying.

We returned the rental car and hopped back on the Cruzeiro do Canal for the journey back across the five mile wide Faial channel to Horta. The skies had cleared up but, as we pulled out of the sheltered harbor, it seemed that all the energy that had formerly been in the sky had just gotten dumped into the ocean.

At first, it was a peaceful ride. Amanda and I sat on the deck and admired a cool volcanic caldera sticking up out of the ocean, named Ilheus da Madalena. But after about five minutes the wind and waves picked up and it felt like we were out on the open ocean. It seemed that the waves were being magnified as the storm pushed the water between the two islands and focused the waves into the narrow channel. Meanwhile, a gigantic, towering lenticular cloud had formed downwind of Pico, indicative of some strong winds aloft.

The captain had the boat pointed at a 45-degree angle to the waves, which resulted in a complicated, nauseating, rolling/pitching/yawing motion. Soon the swells grew higher and higher until they reached probably twelve or fifteen feet. In the trough of a wave, from our seats on the upper deck, you could sometimes look out and see nothing but a big wall of water coming towards you. It was kind of exhilarating, but we really had to hold onto our stuff to prevent it from falling off the deck and into the ocean.

Mercifully, the captain finally pointed the boat into the waves and the roller coaster ride eased up a bit. Now the boat was plowing directly through the waves, sending massive clouds of seaspray billowing across the deck. Fortunately, most of our stuff was already completely saturated from the morning, so we didn’t have to worry about any additional water in our packs. After a half hour we docked safely in the Horta harbor, much to everyone’s relief.

Originally, I had scoped out a site for some stealth camping right near downtown Horta. From the satellite photos, it looked perfect – a nice big, building-less, tree-less hill overlooking the harbor. But camping there wasn’t particularly enticing this evening. The wind was probably roaring ferociously on top of the hill and it looked like it was going to rain again overnight.

Meanwhile, the tent was soaked and I didn’t have any dry clothes left. “How about we stay in a hotel in town?” Amanda suggested gently. “Absolutely,” I answered. A taxi took us to a nice hotel situated right in downtown Horta. It didn’t have a buffet dinner and it wasn’t exactly free, but it sure beat sleeping in a sopping wet tent.

T-plus 20 hours (Horta):

The sun rose brightly on our last morning in the Azores. We caught a taxi to the Horta airport and hopped onto the 10:35am flight to Lisbon. We took off right over the bright blue waters of the Horta Harbor and soon got a spectacular view of Pico Island.

We gazed down upon a thick mound of clouds piled atop Pico Montanha, straining in vain for any glimpse of ground. “Good, hopefully it’s just as bad on Pico today as it was yesterday,” I said, “people should have to work to see the summit.”

Somewhere, down there, underneath all of those clouds, was a special spot – the Pico trailhead. When I arrived at that spot yesterday morning after climbing Pico, I closed the book on one adventure, an adventure to the highest point in Portugal. But also at that spot yesterday, another, bigger adventure had begun. It wasn’t a journey to the top of a mountain, it was a different kind of adventure – it was my adventure with Amanda.