Acoustic data may reveal hidden gas, oil supplies

Just as doctors use ultrasound to image internal organs and unborn babies, MIT Earth Resources Laboratory researchers listen to the echoing language of rocks to map what's going on tens of thousands of feet below the Earth's surface.

The earth scientists are now using their skills at interpreting underground sound to seek out "sweet spots"—pockets of natural gas and oil contained in fractured porous rocks—in a Wyoming oil field. If the method proves effective at determining where to drill wells, it could eventually be used at oil and gas fields across the country.

A major domestic source of natural gas is low-permeability or "tight" gas formations. Oil and gas come from organic materials that have been cooked for eons under the pressure and high heat of the Earth's crust. Some underground reservoirs contain large volumes of oil and gas that flow easily through permeable rocks, but sometimes the fluids are trapped in rocks with small, difficult-to-access pores, forming separate scattered pockets. Until recently, there was no technology available to get at tight gas.

Tight gas is now the largest of three unconventional gas resources, which also include coal beds and shale. Production of unconventional gas in the United States represented around 40 percent of the nation's total gas output in 2004, according to the U.S. Department of Energy, but could grow to 50 percent by 2030 if advanced technologies are developed and implemented.

One such advanced technology is the brainchild of Mark E. Willis and Daniel R. Burns, research scientists in the Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences (EAPS), and M. Nafi Toksoz, professor of EAPS. Their method involves combining data from two established, yet previously unrelated, means of seeking out hidden oil and gas reserves.

To free up the hydrocarbons scattered in small pockets from one to three miles below ground, oil companies use a process called hydraulic fracturing, or hydrofrac, which forces water into the bedrock through deep wells to create fractures and increase the size and extent of existing fractures. The fractures open up avenues for the oil and gas to flow to wells.

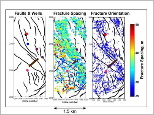

To monitor the effectiveness of fracturing and to detect natural fractures that may be sweet spots of natural gas, engineers gather acoustic data from the surface and from deep within wells. "Surface seismic methods are like medical ultrasound. They give us images of the subsurface geology," Burns said. Three-dimensional seismic surveys involve creating vibrations on the surface and monitoring the resulting underground echoes. "When the echoes change, fractures are there," Willis said.

A method called time-lapse vertical seismic profiling (VSP) tends to be more accurate because it collects acoustic data directly underground through bore holes. "Putting the receivers down into a well is like making images with sensors inside the body in the medical world," Burns said. "The result is the ability to see finer details and avoid all the clutter that comes from sending sound waves through the skin and muscle tissue to get at the thing we are most interested in seeing."

Time-lapse VSP is expensive and not routinely used in oil and gas exploration. The EAPS research team, working with time-lapse VSP data collected by industry partner EnCana Corp., came up with unique ways to look at the data together with microseismic data from the tiny earthquakes that are produced when the rock is fractured. "If we record and locate these events just as the U.S. Geological Survey does with large earthquakes around the world, we get an idea of where the hydrofrac is located. Then we look at the time-lapse VSP data at those spots and try to get a more detailed image of the fracture," Burns said.

The MIT team hopes to show that this new approach is the most effective way to find sweet spots. "If we can demonstrate the value of time-lapse VSP, this tool could be used in a wider fashion across the United States on many fields," Willis said.

—Deborah Halber, News Office Correspondent

This research is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy.