Cyanide & Gold:

Is a US Mining Company Poisoning the People of Honduras?

Jesse Barnes, MIT '02 (Eloranta Fellow, Summer 2002)

Daniel Moss (Grassroots International)

7 p.m., Monday, December 2, 2002

in MIT Room 4-237

This event is co-sponsored with the MIT History Faculty. It is

part of our "It's Our Planet" series, in which members of the MIT

community report on research, activism, or volunteer work they have done across the hemisphere.

After graduating from MIT this year, JESSE BARNES spent

the summer in the village of El Porvenir, in Honduras. El

Porvenir is across a river from one of the largest gold mines

in Honduras, owned by a US mining company. To retrieve gold

cheaply and profitably, the company uses cyanide solution

to leach the precious metal out of the ore. Is this form

of mining poisoning the people and the environment? Jesse's

project aims to find out; and to empower the people of El

Porvenir so that they can continue to monitor the quality of

their environment. Commenting on Jesse's presentation will be

DANIEL MOSS, Development Director at Grassroots International

and former Program Officer for Latin America at Oxfam. Also an

MIT alumnus, Daniel has helped to organize communities in

Peru, El Salvador, the United States, and elsewhere. He will

discuss Jesse's project in the context of what various

international agencies & development NGOs do in Latin America.

After graduating from MIT this year, JESSE BARNES spent

the summer in the village of El Porvenir, in Honduras. El

Porvenir is across a river from one of the largest gold mines

in Honduras, owned by a US mining company. To retrieve gold

cheaply and profitably, the company uses cyanide solution

to leach the precious metal out of the ore. Is this form

of mining poisoning the people and the environment? Jesse's

project aims to find out; and to empower the people of El

Porvenir so that they can continue to monitor the quality of

their environment. Commenting on Jesse's presentation will be

DANIEL MOSS, Development Director at Grassroots International

and former Program Officer for Latin America at Oxfam. Also an

MIT alumnus, Daniel has helped to organize communities in

Peru, El Salvador, the United States, and elsewhere. He will

discuss Jesse's project in the context of what various

international agencies & development NGOs do in Latin America.

For more information:

An article by Robert McClure and Andrew Schneider observes that while cyanide

is not new to the mining business, it is being used more aggressively than ever before:

The leaching technique was used in small measure by miners

in the early 1900s to draw gold and copper out of ore so low

in mineral content that large-scale operators would have

tossed it out as waste.

In the old days, leaching was done by misting cyanide over a

barrel or large vat filled with crushed ore. The cyanide

dissolved microscopic specks of gold from the rock, much as

water dissolves sugar. As gold soared to $850 an ounce in

the early 1980s, mining companies brought back the leaching

technique in a big way, wringing more gold from long-closed

mines and developing new ones where the ore had been

considered too poor to bother.

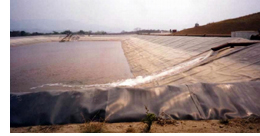

Miners still mix cyanide and water and slowly trickle it

over piles of ore, but the piles are much bigger. Now they

blast away entire mountains of rock, pile the ore in heaps

the size of a football field and apply a river of cyanide,

leaving behind hills of tailings and waste rock.

Environmentalists cringe at the technique, not just because

of the hazard of an accidental cyanide release, but also

because of a long-term risk related to exposure of rock to

the weather. The ore is often high in sulfides, and water

passing through the rock and soil creates sulfuric acid,

which in turn leaches poisonous heavy metals into runoff

water, with iron in the rock turning streams an orange-red.

The article appeared in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer (June 11, 2001).

McGraw-Hill's Integrative Biology Glossary

defines heap-leach extraction as "[a] technique for separating gold from extremely low-grade ores. Crushed ore

is piled in huge heaps and sprayed with a dilute alkaline-cyanide solution, which percolates through the pile

to extract the gold, which is separated from the effluent in a processing plant. This process has a high

potential for water pollution."

The Mineral Policy Center reports

that the use of heap-leach mining has caused environmental damage and harmed human health.

Rocky Ledge Mining Supply agrees:

Cyanide is extremely dangerous to site personnel and the environment. It is an archaic methodology

that has no place in today's world now that there is a better solution.

The company markets a non-cyanide alternative for which it claims a gold-recovery rate that is

higher than that of the usual cyanide leach.

Glamis Gold, Ltd., based in Reno, Nevada, is the owner

of the San Martín gold mine near El Porvenir, where the cyanide heap-leach process is employed.

The Earth Island Institute reports

on another Glamis mining project (in California):

The Glamis Imperial Mine, proposed by Glamis Gold, Ltd.

(trading symbol GLG) six years ago, would be a massive

open-pit cyanide heap-leach gold mine located in the heart

of an area now withdrawn from future mining claims. This

area is adjacent to designated wilderness, critical habitat

for the desert tortoise and an area of critical

environmental concern for Native American cultural values.

The proposed mine has drawn substantial opposition from

Native American tribes, labor groups, environmental

organizations, academia and experts in religion, economics,

the National Historic Preservation Act and water rights.

The Center for Economic & Social Rights tracks the

gold-mining industry in Honduras:

Extraction industries pose a serious threat to the

environment and human health, especially in less developed

countries that [desperately] need foreign exchange. In the

last five years, the Honduran government has quietly granted

mining companies 350 licenses to exploit over 30% of

national territory. CESR has worked with Honduran community

groups to document the human rights effects of gold mining

and have submitted a joint report to the UN Committee on

Economic, Social and Cultural Rights asking the Committee to

ensure that the rights of affected communities are protected

from unregulated mining companies.

The Center's full report is available.

In May, 2001, the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

has noted its concern and made recommendations:

23. The Committee is concerned about the occurrence

of forced evictions, especially among peasants and

indigenous populations and in the areas where mining

activities are conducted, without adequate

compensation or appropriate relocation measures.

[…]

38. The Committee strongly urges the State party to

adopt and implement legislative and other measures

to protect workers from the occupational health

hazards resulting from the use of toxic substances —

such as pesticides and cyanide — in the

banana-growing and gold-mining industries.

38. The Committee strongly urges the State party to

adopt and implement legislative and other measures

to protect workers from the occupational health

hazards resulting from the use of toxic substances —

such as pesticides and cyanide — in the

banana-growing and gold-mining industries.

[…]

45. Given that mining concessions may have a

significant impact on the enjoyment of article12 and

other provisions of the Covenant, the Committee

recommends that applications for mining concessions

be publicized in all the localities where the mining

will take place, and that opposition to such

applications be allowed within three months (not 15

days) of their publication in the relevant locality,

in accordance with principles of procedural

fairness.

46. The Committee urges the State party to adopt

immediate measures to counter the negative

environmental and health impacts of the use of

pollutants and toxic substances in specific

agricultural and industrial sectors, such as banana

growing and gold mining. In this regard, the

Committee recommends that the State party establish

a mechanism by which it can review effectively the

environmental impact studies conducted by or on

behalf of these sectors.

At MIT, other students are working to help ensure clean water in developing countries:

MIT graduating students who did clean water projects in Nicaragua and Nepal took the

top prizes … in MIT's first IDEAS Design Competition for "original innovative

designs that serve a wider community need." A team headed by Rebecca Hwang, a senior

in chemical engineering from Buenos Aires, Argentina, won the $5,000 first prize for her

project on colloidal silver ceramic filters in Nicaragua.

A full report

is available in MIT's Tech Talk (May 22, 2002).

|