Gravitational Waves: Theoretical

Interpretation

Introduction

General relativity states that gravity is expressed as a space-time

curvature, and it predicts the existence of gravitational waves.

Gravitational waves are propagating gravitational fields produced

by the motion of massive objects. They are often called ripples of

space-time curvature. Gravitational fields produced by massive

particles control the motion of matter or light in space-time in a

manner similar to how electric fields produced by charged particles

control how other charged particles move. It is important to detect

gravitational waves because they would bring new information about

distant galaxies which electromagnetic waves cannot. It could also

directly prove general relativity.

How matter emits gravitational waves

According to General Relativity, when any objects with mass

accelerate, they emit gravitational waves. This is analogous to the

electromagnetic waves emitted by accelerating charged particles.

For example, consider a gravitational wave propagating in the z

direction in Cartesian coordinates. The wave only deforms space-time

in the direction perpendicular to its propagation

direction. Deformation of space-time means shrinking and stretching of

the physical length between two points. Gravitational waves affect

space-time in such a way that certain deformation patterns occur

periodically.

If at time t, space is stretched in the x-direction at the maximum

amplitude, then at time t+T/2 (where T is the period), one-half period

later, space will have shrunk by the maximum amplitude and then will

again stretch to its maximum at time t+T, one full period later. The

theory also states that in the y-direction, space is deformed in the

opposite phase of the x-direction. Thus, if space is stretched out in

the x-direction, space is shrunk in the y-direction.

Stretching and Shrinking

The relative length change of two points resulting from

gravitational wave is expressed as

Max stretching & shrinking = hL,

where L is a distance between two points and h is the dimensionless

strain amplitude which is proportional to the second derivative of the

mass distribution of the source and inversely proportional to the

distance from the source. Therefore, the ratio of the stretched length

to the original length is the same for any two points if the

measurements were exercised at the same angle and distance from the

source. However, the longer the original length, the larger the actual

stretching/shrinking effect. This is why interferometers are as large

as 4km and larger ones are being developed. The fact is that motion of

the existing matter in the universe limits h to the range of less than

10^(-21). A 10km interferometer will be able to detect length changes

of 10^(-17)m, which is certainly technically challenging since various

sources of noise make it difficult to distinguish the gravitational

wave. Gravitational waves have not yet been directly detected by this

method.

Sources of detectable gravitational wave

Binary system

The magnitude of the gravitational waves depends on the

distance from the source and the second derivative of the mass

distribution (mass times acceleration in case of one

particle). Thus, one must consider very massive objects moving

violently as the candidates for the sources of detectable

gravitational waves. The most promising candidates are compact

binaries consisting of either two neutron stars, two black holes

or one neutron star and one black hole. They are small and heavy,

which allows them to orbit at a closer distance and at a high

orbital frequency, which means that the second derivative of the

mass distribution of the system is large. Therefore, the system

emits strong gravitational waves. Compact binaries have another

interesting aspect associated with gravitational radiation

(explained in a later section).

Rotating neutron stars

If non axis-symmetric along the rotation axis, a rotating

neutron star will emit gravitational waves. If symmetric, the

second derivative of the mass distribution holds constant at zero

in the system, which leads to no gravitational wave emission.

Supernovae

Supernovae are a good gravitational source. They are compact

and have large accelerations. Similar to rotating neutron stars,

if a supernova's explosion has axial symmetry, gravitational waves

will not be emitted for the constant mass distribution. Initial

density and temperature fluctuations and other factors may direct

asymmetric collapse. If a supernova, which is exceptionally

bright, is observed in gravitational wave, we will be able to test

a prediction of general relativity which states that the speed of

gravitational wave is the same speed as light.

Stochastic background

This comes from the density fluctuation of the early stage of

the universe. Measuring the background would tell us about the

nature of the Plank-size universe and provide clues for testing

the various cosmological models. Although stochastic background is

interesting, it is so weak that modern technology is far from

achieving this task.

Relation between the motion of the source and the period and the

amplitude of the consequent gravitational wave

The magnitude of gravitational waves is proportional to the second

derivative of the mass distribution of the emitting system and

inversely proportional to the separation of the source and observing

point. The next question that arises is how the period of a

gravitational wave is related to that of the motion of the source. If

the binaries are in a circular orbit, the resulting gravitational

waves have a frequency that is twice that of the binary system--that

is, the period of the gravitational wave is one half of the orbital

period.

The magnitude changes with the orientation. However an

angle-averaged estimate of the signal strength is expressed in the

following formula.

missing formula

To see why this is proportional to the second derivative of the

mass distribution of the system, recall that the derivative is

proportional to  and inversely

proportional to

and inversely

proportional to  .

.

This leads to the above equation. Therefore, if the frequency of

the orbital period increases, the resulting gravitational wave will

also increase its frequency and amplitude. And this is achieved by

self-energy loss of gravitational radiation.

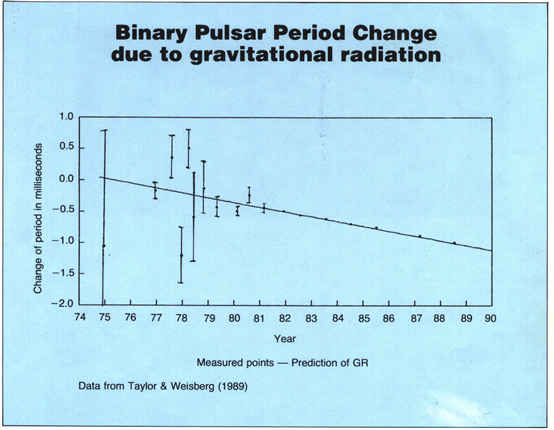

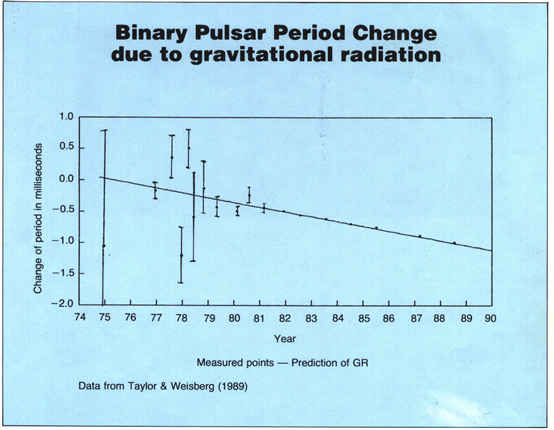

Gravitational radiation and self-energy loss of binary system

According to general relativity, gravitational radiation takes

energy from its source. The energy loss results in the smaller

separation of the binaries and therefore shorter orbital

frequency. This comes from the fact that the rate of change in orbital

period of a binary system is negatively proportional to the rate of

change in gravitational potential energy of the binary system:

,

,

where m is the gravitational mass of the primary star and M is the

total gravitational mass of the binary system. The gravitational mass

m is the sum of the rest mass and the total self energy of the

gravitating body.

As the system radiates gravitational energy, it decreases its

orbital period. Therefore, the resulting gravitational wave has a

waveform of increasing frequency and amplitude. Furthermore, the

radiation energy is proportional to the square of the amplitude of the

associated gravitational wave. This means that the radiation power

increases faster and faster as the system loses its energy due to

gravitational radiation and thus resulting in the larger rate of

change in orbital period. In fact, the final stage of the binary

system consisting of two neutron stars has such a large radiation

energy that the neutron stars will lose all their potential energy and

finally collide. The waveform resulting from the collision will be

very rough. Looking at the waveform, we can also obtain information

about the mechanism of astronomical events.

Collision of two neutron stars

Binary Neutron Star Merger, calculated by Maximilan

Ruffert

Black Hole - Neutron Star Binary Mergers

Why is it important to measure the gravitational wave?

Gravitational waves are most unique in that they propagate without

interacting with matter. This allows us to obtain new information

about the universe that electromagnetic waves fail to provide. The

amplitude and frequency of gravitational waves describe the frequency

and mass of the emitting source. The shape of the final phase of a

binary system might give some new insight in astronomy. Stochastic

background would reveal the mass distribution of the early plank-scale

universe and the evolution of the early universe.

and inversely

proportional to

and inversely

proportional to  .

. ,

,