refer+ing, the result

that you get is refering instead of referring.

The direct technical problem here is that whenever Kimmo attempts to add the

second "r", gemination15 fails. Essentially, the doubling of the

letter "r" is only permitted by gemination15 if it is in state 14.

However, without a symbol to indicate the stressed syllable in the word,

it won't ever do anything aside from staying in state 1 or rejecting.

Practically, we need to always provide the stress indicator for these

machines to work, and indeed generating from the string re`fer+ing

works properly, as shown in this screenshot:

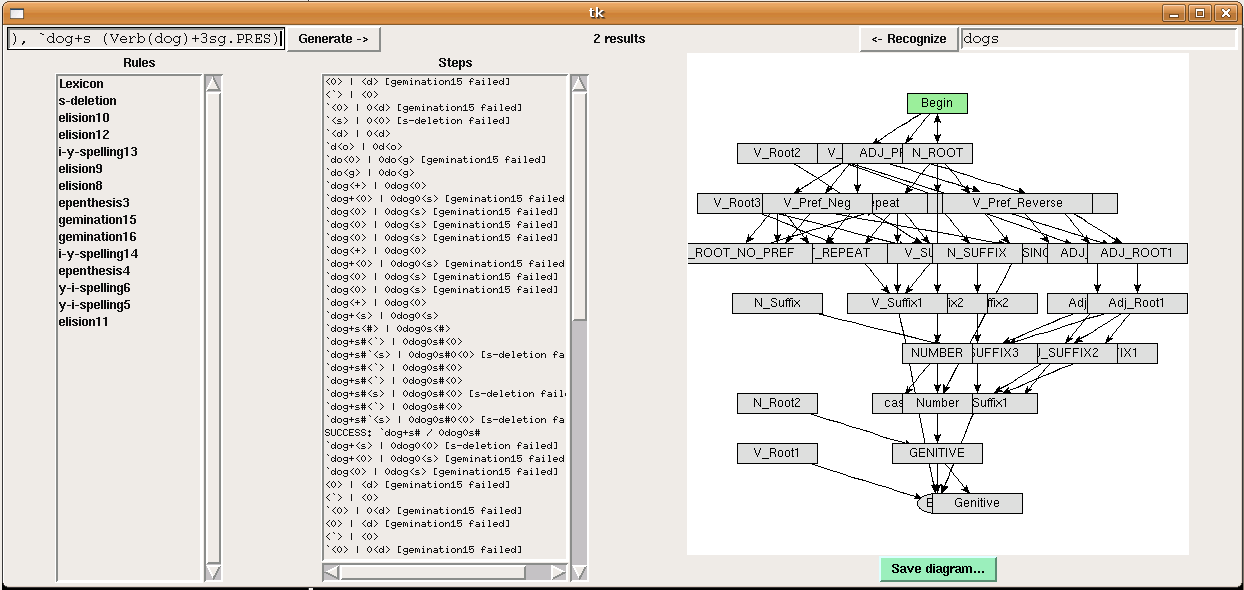

dogs is

`dog+s (Noun(dog)+PL). I added "dog" as a verb by putting

the following line in the V_ROOT_NO_PREF section of the

lexicon:`dog AfterVerb Verb(dog)

flier, it at first

appears that the system is making more than one left-to-right pass across

the word to find it. However, this is not strictly speaking the case.

It is making a single pass across the word, and backtracking as far as

necessary when it fails. In this case, it fails after it has gone through

most of the word and finds that it needs to backtrack pretty much all the

way to the beginning. That is, essentially Kimmo is running a depth-first

search. This means that while Lauri Kartunnen's quote claiming that "the

recognizer only makes a single left-to-right pass through the string as it

homes in on its target in the lexicon" is technically not wrong, there are

some cases in which it will appear to be misleading.

The actual issue that causes Kimmo's recognizer to have to backtrack all

the way in this case can be identified by stepping through the recognition

steps and watching the states that the lexicon is in. Up until the point

of backtracking, most of the states hint that it is trying to recognize

"flier" as a form of the noun "fly." Beyond the backtracking, most of

the lexicon states hint that it is trying to recognize "flier" as a form

of the verb "fly." Thus, we may expect to see this sort of behavior when

the root of a word may be used as multiple different parts of speech.

This behavior will not occur with generation because generation

only cares about spelling change rules, and since it doesn't care about

parts of speech at all, it makes no use of the lexicon. This is the key

way in which it differs from recognition.

Success, the machine does not actually

loop back at all. What is actually happening is just a continuation of

the depth-first search that it has been conducting all along. Misunderstanding

this is a result of failing to grasp the crucial point that the rules

should not be thought of as driving the process of generation to some end;

instead, the rules are filters, whose only purpose is to weed out

and reject the impermissible words. Kimmo needs to generate all

allowable words, and so it must eventually travel all the branches in its

depth-first search until each one either results in a complete valid

word, or is rejected by one or more of the filters (rules).

rule12.yaml appear in,

the output is kampat. The lab asks us to compare this with

what we hypothesized, and in fact this exactly matches what I expected to

happen, having read the Kimmo documentation that was suggested. However,

someone who had not yet familiarized themselves with the way Kimmo worked

would have expected the rules to be applied in the opposite order from

that order which they appeared to be applied in previously.

This is not the case because Kimmo does not order rules at all; all

the rules apply simultaneously, and can reference information in both

the underlying lexical representation and the surface form. They don't

feed one another; they each simply limit what the outputs from the total

system may be. There is, of course, another reason someone with the

above hypothesis would be confused... if rule 1 had been applied and

then rule 2 had been applied, the expected output would be kammat,

but it was actually kampat. Perhaps this is actually an

error in the way these rules are ordered in the lab.

Rather than take the rules as originally written in the lab, I felt

that the syntax used there was insufficiently expressive in that it doesn't

reflect the true two-level nature of the Kimmo engine. Specifically,

it doesn't specify whether the various elements of the environments are

constrained with respect to the lexical form, the surface realization, or

both. Thus, considering the generation we wished to happen, I rewrote the

rules in the much more expressive syntax outlined in the Kimmo documentation,

and proceeded to compile those into FST tables, discarding the original

implementations entirely. In essence, I think the problem was posed in

a strange way, and that suggesting that we modify the machines to interact

"better" is going about the problem the wrong way - properly written

two-level rules should not have to care much about one another, and if

the rules are expressed correctly at the outset, this problem shouldn't

exist in the first place.

The rules I implemented in my file, corresponding to the functions performed

by the original rules, are as follows:

# p:m <= @:m ___

p realized as m: |

FSA

p @ p @

m m @ @

1: 1 2 1 1

2. 1 1 0 1

# N:m <= ___ p:@

N realized as m: |

FSA

N N p @

m @ @ @

1: 1 2 1 1

2. 1 2 0 1

kammat from kaNpat

while rejecting kampat.

>>> k=load("rule12mine.yaml")

>>> print list(k.generate('kaNpat', TextTrace(3)))

p realized as m: 1 => 1

N realized as m: 1 => 1

k

k

p realized as m: 1 => 1

N realized as m: 1 => 1

ka

ka

p realized as m: 1 => 2

N realized as m: 1 => 1

kaN

kam

p realized as m: 2 => 1

N realized as m: 1 => 1

kaNp

kamm

p realized as m: 1 => 1

N realized as m: 1 => 1

kaNpa

kamma

p realized as m: 1 => 1

N realized as m: 1 => 1

kaNpat<#>

kammat<#>

p realized as m: 1 => 1

N realized as m: 1 => 1

kaNpat#

kammat#

SUCCESS: kaNpat# <=> kammat#

kaN

kam

p realized as m: 2 => 0

N realized as m: 1 => 1

['kammat']