A Machine for Climate:

The House Beautiful/AIA Climate Control Project

1949-1952

2.2 | History

A Crisis of Fuel and National Identity

The increased importance of suburbia does not necessarily establish it as a problem, but rather as an important site for the application of solutions. With concerns of fuel shortage on the minds of scientists and interests in building technology and American identity on the minds of architects, the suburbs became one site of population concentration to which improvements could be posed.

In terms of fuel, the threat, as of 1953 was not an one of an immediate lack. The threat was based rather in the existence of abundance. 'As we shall see,' wrote Harrison Brown in his book The Challenge of Man's Future, 'we are now living in a phase of history which is destined never to be repeated. For the fifth of the world's population that lives in regions of machine culture it is a period of unprecedented abundance. And most of us who are a part of the fortunate one-fifth are so enamored with the achievements off the last century and with the abundance which has been created that we believe the pace of achievement will continue uninterrupted in the future... Whether or not it survives depends upon whether or not man is able to recognize the problems that have been created, anticipate the problems that will confront him in the future, and devise solutions that can be embraced by society as a whole.'4 Finding a solution to the problem, according to Brown, required 'an understanding of the relationships between man, his natural environment, and his technology.'

By the turn of the mid-century, scientists, economists, and historians were becoming aware of America's unprecedented dependence on fossil fuels and mankind's unprecedented technological innovations. While these changes in society did not create a need or lack, their unprecedented nature ignited the query of what this meant and what creative steps could be taken to both limit our dependence on fuels while applying the new technological innovations. 'By 1950 the shift to machine power had changed America from a rural agricultural nation to an industrial colossus in which the individual inhabitants had more material possessions than the inhabitants of any previous or any other contemporary society. Productivity per man-hour had climbed to more than five times the level that had existed a century previously. Three-quarters of the population of 150 millions persons were urbanites. Less than 13 per cent of the labor force was engaged in agricultural work. Human and animal power, both on the farm and in the factory, had become insignificant when compared with the huge amount of mechanical power available.'5

Concerns emerged mid-century that the nation would have trouble meeting these future demands. Other rumblings of the pumping of ground water and deforestation provided worries for the future based in anxieties developed from the past (i.e. the Dust Bowl and Great Depression).6 By 1947 the United States was importing more petroleum products than it exported, '[y]et it was predicted that during the period 1950 to 1975 both population and per capita consumption would expand further, resulting in greatly increased total consumptions of most raw materials. It was predicted that although the population would increase only an additional 25 to 30 percent during that period, consumption of electrical energy would increase nearly fourfold, consumption of petroleum would more than double, steel production would increase 50 per cent, aluminum production might increase fivefold, and demands for copper and zinc might increase another 80 per cent.'7

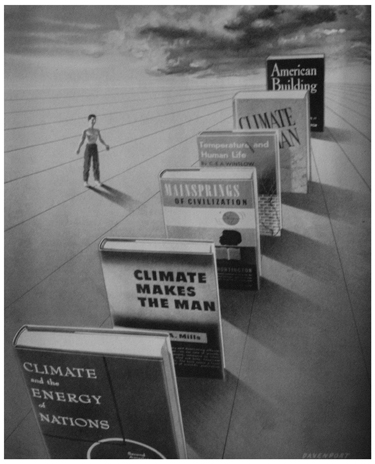

Image of climate literature is from October 1949 issue of House Beautiful magazine.