"What is often being argued, it seems to me, in the idea of nature is the idea of man; and this not only generally, or in ultimate ways, but the idea of man in society, inded the ideas of kinds of societies." --Raymond Williams, Ideas of Nature

In the introduction to “Philadelphia Murals and the Stories They Tell”, Jane Golden, Executive Director of The City of Philadelphia’s Mural Arts Program, writes:

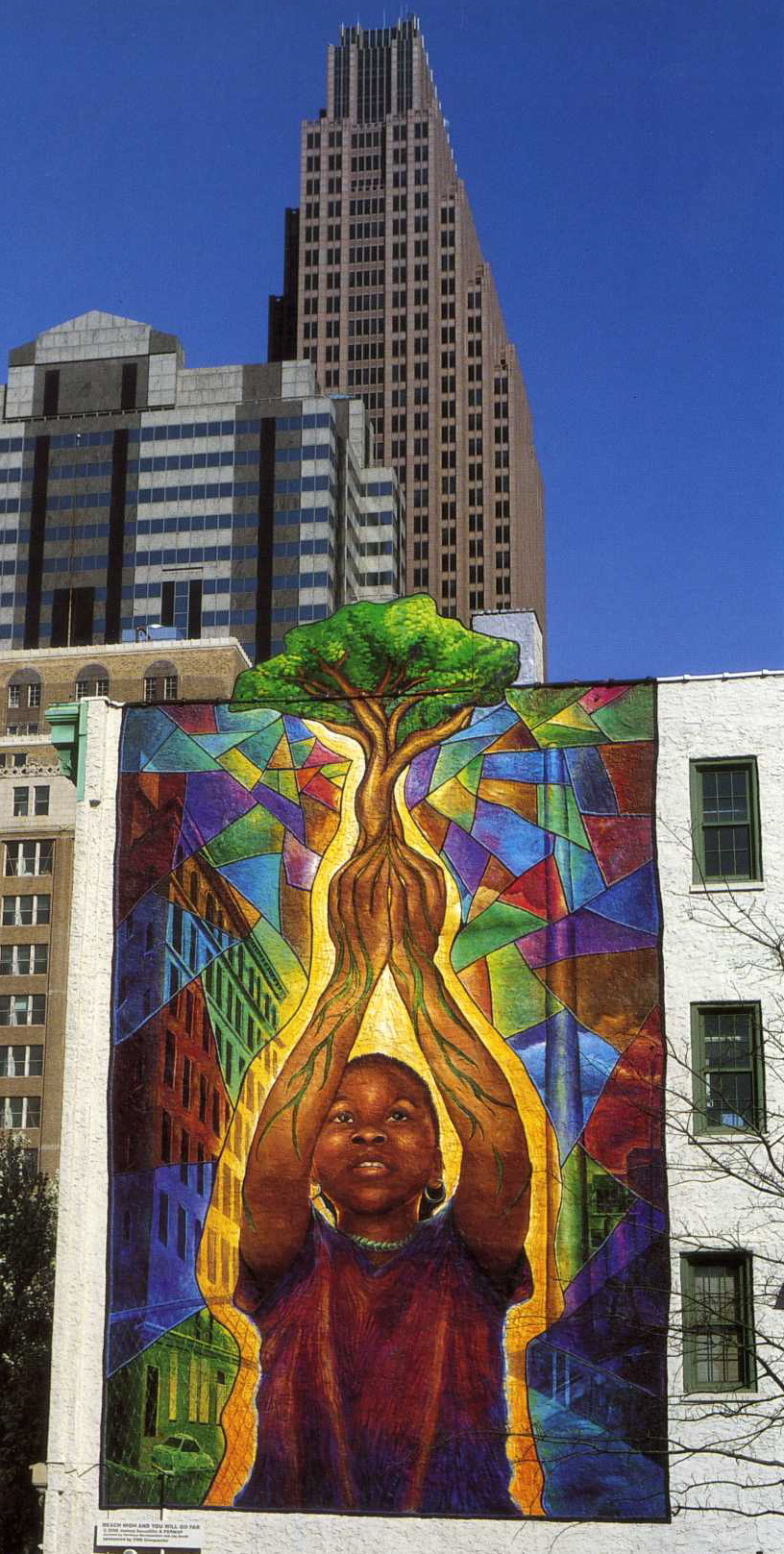

“Murals have this kind of personal impact. They engage you, stir questions, make you see things in new ways. I don’t know whether it is their intense color, imposing size, or symbolic power, but they seem to be imbued with a mysterious energy that radiates outward, touching everyone who sees them… The murals’ images and themes reflect aspects of ourselves we rarely take the time to articulate but which nevertheless strongly influence our lives.”

Indeed, there is something about murals that catches our attention, perhaps distracting us from whatever contemplative process we were engaged in at the moment, sending our thoughts to a different time or place engraved in memory – our own, or someone else’s. As one classmate commented, “Whether enjoyed or abhorred, [murals] do stir our emotions and force us to take notice if only for a fleeting moment.”

The trigger of that fleeting moment itself – the mural – and the process and program that brought that mural to being, are each at the core of this project. In this research I examine some of the ways that murals – as a form of public art in urban spaces– have been used to create place identity, and further, how ideas of nature – so often considered to be the antithesis of “urban” -- play a role in shaping this identity. I examine the self-selected “City of Murals” in Toppenish, WA, the Balmy Alley Project in San Francisco, CA that is now managed by the Precita Eyes Mural Arts Association, and the Mural Arts Program of the City of Philadelphia, PA.

“In the beginning there was the story. Or rather: many stories, of many places, in many voices, pointing towards many ends.” --William Cronon, A Place for Stories: Nature, History, and Narrative

Toppenish, WA

“While in Toppenish you’ll want to make time to wander its streets with old fashioned street lamps and grab an espresso or old fashioned soda while you check out what we have to offer. This small city’s pride and joy are 70 painted outdoor, historical murals. The mural project depicts events, men and women that have made lasting contributions to the city. The murals can be viewed year round. May through September you can jump on a horse drawn wagon for a narrated tour with a little colorful local lore thrown in for good measure." -- From the Toppenish.net website

Toppenish, WA is a small city in the Yakama Valley of Washington. Recognizing that its location within the Yakama Indian Nation and its historic experience as the location of the Treaty of 1855 between natives and settlers, was a major asset the Toppenish Mural Foundation was formed in 1989 to transform the city’s walls into a medium for narrating the place’s history and turning it into a “city of murals”. This was above all else an effort to revitalize the declining area through beautification and tourism, so the murals played an important role in the city’s economic development efforts. The program is now operated through the Chamber of Commerce, which offers tours of the murals, and organizes the process of producing new murals through events such as the annual Mural-A-Day project on the first Saturday of every June. The Mural-A-Day project is itself an economic development venture, as it essentially serves as a food, arts, and craft festival organized around the production of a new mural, where mural artists paint throughout the day for visitors and residents to watch.

According to a 2003 article in the Seattle Post, the murals “need to meet rigorous standards set by the foundation, and mural suggestions must be historically accurate and feature a person or activity from 1850-1950.” This regulation is an intriguing element of the process, as it creates a limited view of the area’s history. An overview of the mural gallery begs the question of whether, by starting the town’s history around the time period of white settlement in the Yakama Valley, the history of native life before the arrival of settlers is misrepresented or ignored.

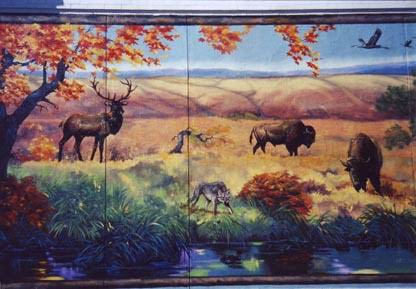

The above image, titled Wildlife and captioned as a "mural [that] depicts wildlife native to this area prior to its settlement," is one of the few images that attempts to depict life in the Yakama Valley before 1850. The landscape evokes the calmness and peacefulness of coexisting western game, but also suggests that “prior to its settlement” no human life existed in the valley. This in fact highlights one of William Cronon’s key observations about narrative, in his piece entitled "A Place for Stories." He writes: “where one chooses to begin and end a story profoundly alters its shape and meaning” (Cronon, 1364).

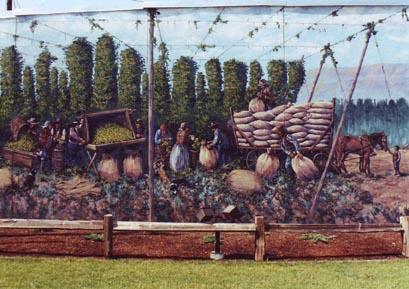

To be fair, a large number of the Toppenish murals do in fact depict important native individuals, but many of these images exacerbate social myths about Native American experiences. The below image, titled When Hops Were Picked by Hand, for example, carries the following caption: “The mural… shows an early hop harvest when the crop was picked by hand. This was usually done by Indians from all over the Northwest, who came to the Toppenish area each year with their families, pets and chickens. They set up small Indian villages of teepees at the hop fields, staying until the harvest was complete.”

This caption not only suggests that Indians were “guests” on settler’s land, but its language coupled with the image of natives working peacefully in the rural landscape idealizes the experience and redefines the meaning of the landscape in its relationship to natives. Cronon explains a similar phenomenon in discussing Worster’s narrative of the Dust Bowl: “Although he acknowledges the prior presence of Indians in the region, he devotes only a few pages to them. They are clearly peripheral to his narrative... If we shift time frames to encompass Indian past, we suddenly encounter a new set of narratives… As such, they offer further proof of the narrative power to reframe the past so as to include certain events and people, exclude others, and redefine the meaning of landscape accordingly” (1364).

The Toppenish murals certainly offer a questionable narrative of the past, but when we examine the San Francisco murals, we begin to see that a determining force in this questioning often has more to do with the narrator, rather than the narrative itself.

San Francisco, CA

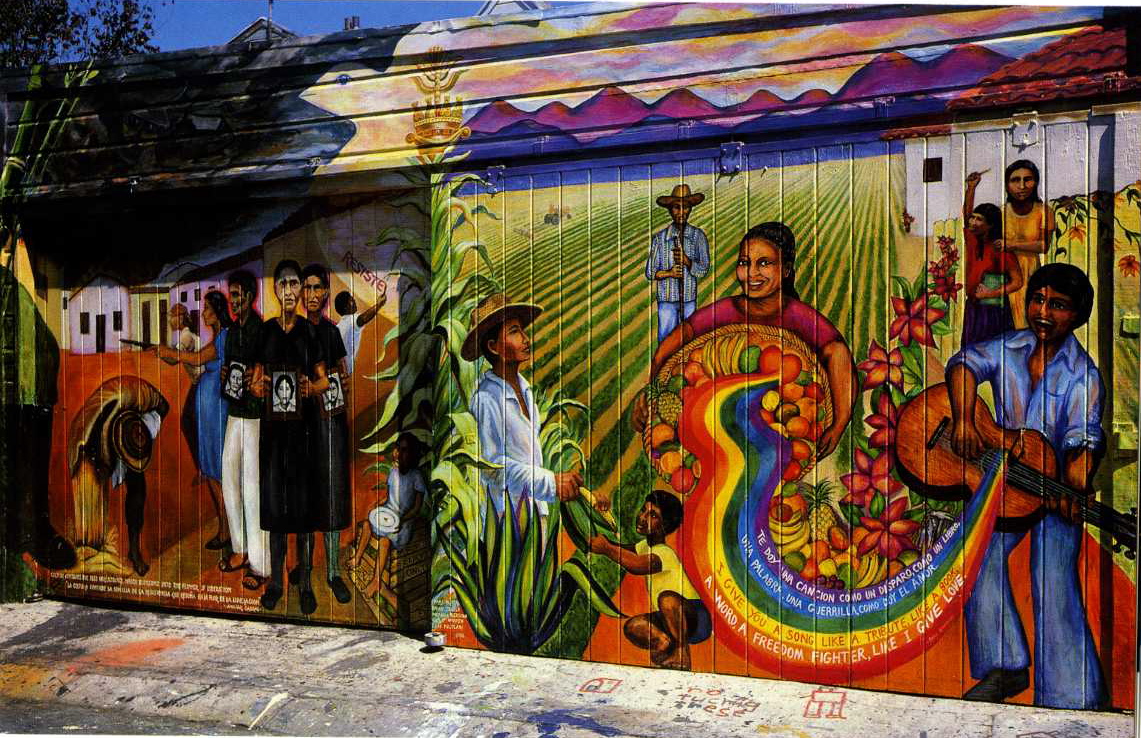

The Balmy Alley Project in San Francisco’s Mission District was initiated in 1984 by a group of mural artists that were actively painting throughout San Francisco and the Mission District. In the 1930s the Mission District started shifting from a predominantly Irish base to the core of the Latino community: a process that was exacerbated by the construction of the Bay Bridge, which displaced many Latino communities, and new immigration laws that brough thousands of Latin American immigrants to the city (Drescher). By 1984 San Francisco already had a thriving mural movement, which was influenced by the tradition of public art and murals in Mexico and other parts of Latin America; this tradition complemented the political activism that existed in the bay area throughout the mid to late 20th century. When funding for the Balmy Alley Project was secured in 1983, over 30 artists active in the local movement came together to create 27 new murals in the alley. The murals reflected themes relevant to the lives of the areas Latino populations, this translated into the dual themes of opposition to US involvement in Central America, and a celebration of Central America’s indigenous cultures. In many of the murals, these themes incorporate ideas of nature to convey their political message:

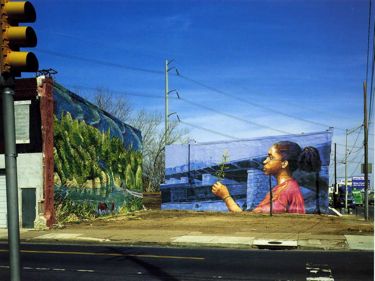

The above image, titled Culture Contains the Seeds of Resistance which Blossoms into the Flower of Liberation, uses the rural agrarian landscape as a metaphor for indigenous culture, which has its roots – and thus contains its seeds -- in Central America; we know that this landscape is somewhere in Central America because in the bottom center of the image a young girl is sitting on a box of harvested crops that reads “for export only.” Metaphorically, the landscape (and thus their culture) contains the seeds that give its people strength to resist the oppression experienced at the height of US involvement in Central American politics and agriculture policy. The image also expresses the idea of resistance “flowering” into a sense of freedom, as the rainbow reads: “I give you a song, like a book, a work, a freedom, like I give love.” In the below image, titled Indigenous Beauty, we see another agrarian landscape tucked under mountains and a blue sky: men are farming while women attend to children and harvest flowers. The scene is idyllic and shares a sense of romanticizing-the-past with the Toppenish murals. This thread, however, highlights the importance of the process and production of the murals itself: Indigenous Beauty was initiated by a community of individuals representative of the indigenous culture itself, whereas the Toppenish murals were developed through the Chamber of Commerce for economic development purposes. This distinction makes the romanticizing of a past life more palatable to the conscious viewer. The Balmy Alley murals are now operated by the Precita Eyes Mural Arts Association, a non-profit organization founded in 1977 by mural artist Susan Cervantes, who worked closely with San Francisco’s famous Las Mujeres Muralistas (The Women Muralists). “Precita” literally means “little dam”, and refers to a small dam that once crossed Mission Creek, now existing under the neighborhood’s Precita Park. As a non-profit they engage in community development projects through arts and arts education; they help design and construct community murals throughout the city as they are requested by community groups.

“Place memory encapsulates the human ability to connect with both the built and natural environments that are entwined in the cultural landscape. It is the key to the power of historic places to help citizens define their public pasts: places trigger memories for insiders, who have shared a common past, and at the same time places often can represent shared pasts to outsiders who might be interested in knowing about them in the present.”

--Dolores Hayden, The Power of Place

“It is undoubtedly true that we all constantly tell ourselves stories to remind ourselves who we are, how we got to be that person, and what we want to become. The same is true not just of individuals but of communities and societies; we use our histories to remember ourselves” (Cronon, 1369)

“If we alienate the living processes of which we are a part, we end, though unequally, by alienating ourselves.” – Raymond Williams, Ideas of Nature