Portrait of A. P. Trotter by Alphonse Legros (1895).

© Trustees of the British Museum.

Alexander Pelham Trottter did many things in the nine decades of his now all-but-forgotten life, among them essentially founding, as a scientific discipline, the entire branch of engineering concerned with street-lighting and open-air illumination. Although he spent years in public service and was a (largely unheeded) senior technical-advisor to the British government during the First World War, he hated the ever-growing bureaucracy (which he blamed for the slaughter in the trenches), and, as noted elsewhere on this site, was among the few champions of Mrs. Hertha Ayrton, whose career (and with it perhaps the advance of whole fields of physics) was stalled by the sexism and anti-Semitism of the British establishment. He was an early adopter of every new technology, but a student of old technology as well: his article "Stonehenge as an Astronomical Instrument" (he doubted it was) appeared in Volume 1, Number 1 of Antiquity. A radical within the system ... an internationalist in a time of jingoistic xenophobia ... one of the great electrical-engineers of his generation ...

Not quite so good as a poet, though.

Wormhole by Les Bossinas [NASA]

TIME TURNED BACK:

A Poem by A. P. Trotter

[Knowledge 4, 362 (1883)].

Trotter's words are in

bold.

-

Bring out Imagination,

And we'll put her to the Car,

And harness fitful Fancy,

For to-day we travel far,

-

Due northwards our direction,

And through chilly gloomy space,

One hundred six' five billion miles --

And at a rattling pace.

-

Now stop, and turn our telescope

Towards the distant Earth,

And we shall shortly see how much

Our expedition's worth.

To the middle of the field ;

Slip on a higher power

That will good definition yield.

That we've never seen before,

And 'tis as though we stood

Before a lowly cottage door ;

There's an aged woman sitting

In an arm-chair by the fireside,

Feebly toiling at her knitting.

Bursting through the cottage door?

'Tis her son -- and see, she knows

His footstep on the sanded floor --

No more battles, night alarms,

No more hardships and privations --

Leave him in his mother's arms ...

Of light : 'tis quickly reckoned.

You'll find 'tis nigh three seven' three

Thousand miles through Space per second.

There's a sight that makes one glad,

As the thankful mother kisses

The brown cheeks of her dear lad.

With outstretchèd arm ;

The good old lady sinks into

Her chair, and with a calm

In the firelight, gently rocking,

Is quietly at work,

But is unpicking her new stocking.

(His strong arms are still stretched out)

Backs through the door which opens

Of itself to let him out.

Shows us plainly, if we wait,

We shall see the soldier's mother,

Who now wipes a pewter plate,

Would surely turn us pale,

So over the description

We had better draw a veil.

Evening, After Rain by Benjamin Williams Leader (1886).

To him it's not surprising

That in the glowing western sky

The evening sun is rising,

With never-ceasing clack,

Makes grain from flour, and with the wheel

It laps the mill-stream back,

Where gurgling eddies gleam,

Nodding their heads, bend forward

Against the rapid stream.

Kinburn, Ukraine, 1855 October 17.

For Fancy knows no limits.

The story of the previous weeks

Whirls by in a few minutes.

The ships stern-foremost skim :

Whoa ! Slacken speed to former rate

For see, the air grows dim,

The battle's all around,

But as we have no telephone

There's not the slightest sound.

'Twill be better, if you please,

To travel at a slower rate,

And see things at our ease.

Diorama, Regimental Museum of the Argyll &

Sutherland Highlanders [Photo: Kim Traynor]

And he ought to think it fun,

For here the clouds of smoke

Grow thicker, rolling t'wards the gun.

And with a blinding blaze,

The shot comes up and drives them down

The barrel as we gaze.

The Valley of Death.

A dispatch by Raglan signed ;

The pencil gliding to the right

Leaves paper clean behind.

Does not seem so very sad,

For the dead on all sides rise up,

Although many wounds are bad ;

Leaving unharmed skin,

And, finding their respective muskets,

With a flash go in.

And soon the cannonadings cease,

The troops march backwards to their camps,

And all again is peace.

Serpens Caput: "twice as far as is Arcturus". [Animation by MicheletB]

Attraction should allure us,

For now we're more than twice as far

As Earth is from Arcturus.

To witness bygone scenes,

But it is not unthinkable

To us by any means.

We cannot but obey :

This does not contradict the laws

Of Thought in any way.

Rather a cross between William Topaz McGonagall and Martin Amis, to be sure, but there are salvageable bits. If I were rewriting this -- for a steampunk song, perhaps? -- I would certainly cut 11-15, and probably put 30 or 31 near the beginning. But a few lines are quite good: Nodding their heads, bend forward // Against the rapid stream, for instance, or The cartridge-cases fill, // And soon the cannonadings cease.

Trotter's contemporaries do not seem to have been much taken with "Time Turned Back"; I am unaware of any reference to it beyond its original publication. On that occasion, the editor of Knowledge, Richard A. Proctor, remarked that "I find so much that is really scientific, as well as amusing, in Mr. Trotter's poem that I have inserted it as it stood. I had occasion to make a little note upon one part of it, and as I found a prose note had a comical effect I ran the note (with as little change as possible) into rhymed form:

Just here I would throw in a note

Suggested by this poem

(On things thát we can surmise

Though perchance we'll never know 'em).

This voyager in space,

As our deponent seems to say

Saw more than had elapsed

Within the compass of a day ;

But all that time the Earth

Was swiftly turning without jars,

And the places seen from far away

Were turned towards diff'rent stars.

So to see those places clearly

During several days expiral,

Our traveller must have voyaged

In a most amazing spiral.

See this subject lightly touched on

In my cheerful little treatise

Called

Geometry of Cycloids

Which for seaside reading meet is.

It's advertised, I notice,

In the outside sheets of Knowledge

But the bulk of it I worked out

In my salad days at College."

(Proctor, too, was a Victorian polymath whose strong point was not comic verse!)

Richard A. Proctor [Wikipedia]

The existence of some connexion between superluminal velocities and time travel was at least intuited long before Einstein, probably soon after the realisation that the speed of light is not infinite. Looking at the stars (as every populariser of astronomy in the last four centuries has most likely remarked) is looking into the past, seeing them when the rays of their light departed. Likewise, observers hundreds of light-years away see us not as we are now, but as we were centuries ago.

(Of course, relativity makes these statements a bit less self-evidently correct, but never mind that -- one still hears them today.)

Therefore, if one could only race away from the Earth at a speed outstripping light's, then turn around, one would see the past.

Trotter's effort aside, there are several literary treatments of the underlying conceit, works in which time unspools before a distant observer. Among the most elegant is the prose-poem "Lumen" by the astronomer-visionary Camille Flammarion in his Récits de l'infini [Paris: Didier, 1873] (English translation Stories of Infinity [Boston: Brown, 1873]) -- science fiction, but of a type completely different in tone and content from that of his contemporary Jules Verne. Flammarion's dream-like tales will be the subject of a future blog-entry here, but they share little beyond their subject with "Time Turned Back".

Bernafay Wood, 19 July 1916 by Ernest Brooks.

Alexander Trotter's wife Alys was a far more talented poet than he; some of

her anguished Great War verse (notably

"The Hospital Visitor") is still read -- and still painful --

today. She was also as an

historian of South Africa. If Alexander Trotter was ahead of his time

as an engineer, Alys Fane Trotter was ahead of hers as a scholar. Her most

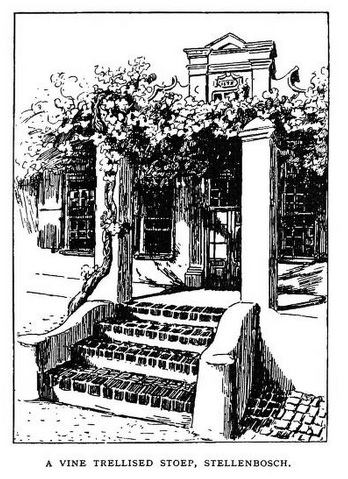

significant book,

Old Cape Colony: A Chronicle of Her Men and Houses

[London: Selwyn & Blount, 1903], told the story of the Dutch settlers

largely through their material domestic culture -- very much a

Twenty-first Century approach, although unusual enough in 1903 for

her to modestly insist "This is not a history". She illustrated the

book herself, and her sketches are of enormous value in their own right.

As she said in the preface: "Calamity falls on houses as well as on

people. I learn that to several buildings has come, since I drew

them, that worst of fates, 'modern improvement.' I make no apology

for including the drawings of houses that can never be seen again ..."

FURTHER READING: