From

Science -- Invention -- Discovery -- Progress

A Pictorial Library for Home Reading, covering all the very latest events in the Workshops of the Industrial, Scientific and Natural World

A graphic account of the amazing achievements which best tell of the genius, spirit and energy of the age and depict the grand march of improvement in the various domains of human activity. (Wonderful indeed is this world's workshop, for its doors are open wide and all that is within can be seen and understood -- whether it be in an airship above the clouds, upon or under the sea, in the city, town or country; all that has been wrought by man for the progress and advancement of the world is arrayed under the broad head "The World's Workshop".)

A Comprehensive Volume of live subjects so presented as to make it equally adaptable for pleasant reading, ready reference, accurate instruction or careful study.

By

W. J. JACKMAN, M. E., Author of "Flying Machines, Construction and Operation,"

"A B C of the Motor Cycle!" "Facts for Motorists," etc.

TRUMBULL WHITE, Noted Traveler and Author

and

FERDINAND ELLSWORTH CARY, A. M., Celebrated Historian and Writer

Embellished and Illuminated with

FIVE HUNDRED PHOTOGRAPHIC

ILLUSTRATIONS

[Chicago: L. H. Walter, 1911]

All text in bold is from The World's Workshop. Internal quotations in italics are from the inventor and polymath Sir Hiram Maxim.

PROGRESS IN METHODS OF NAVAL WARFARE

If it be true that the most certain way to put an end to warfare is to make war more terrible, we should include the Krupps, the Gatlings and the Maxims in the list of our true promoters of peace. Improved artillery, rifles, armor plate and explosives have been devised of late years with a rapidity not second to industrial inventions.

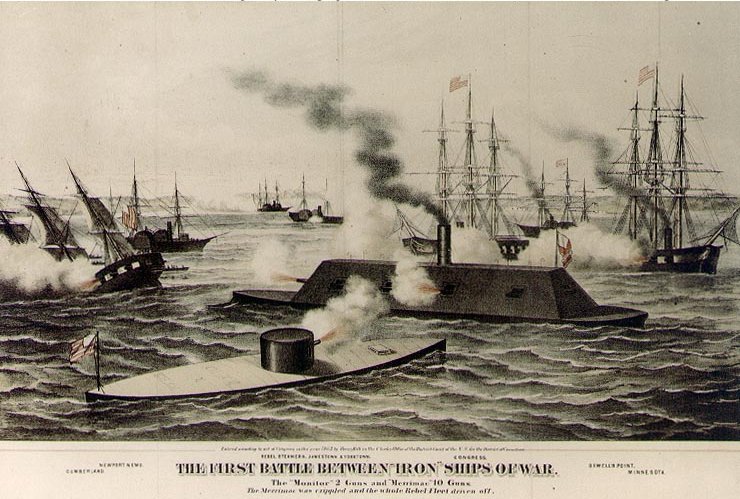

The world's naval wisdom received a surprise and a shock when Ericsson's little iron-sided Monitor fought its duel with the ponderous Merrimac, ribbed with railroad iron. American ingenuity, both north and south, had grappled with the problem of invulnerable warship construction, ignoring absolutely all other naval architects of the world and their cumbrous lore. Slow-going conservatism had to be abandoned, and the old wooden hulks then constituting the navies of the earth's great powers were doomed to the scrap heap.

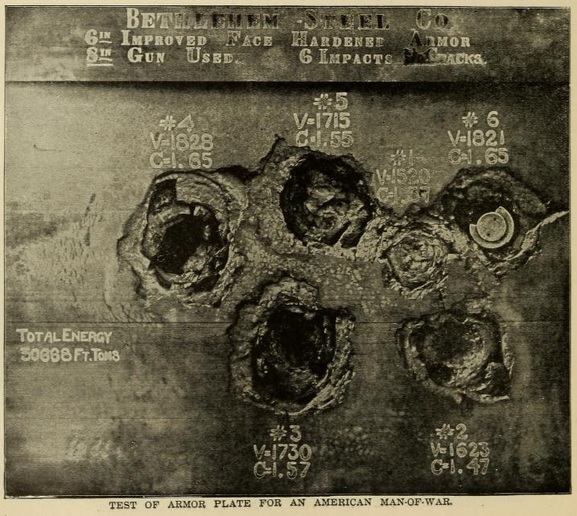

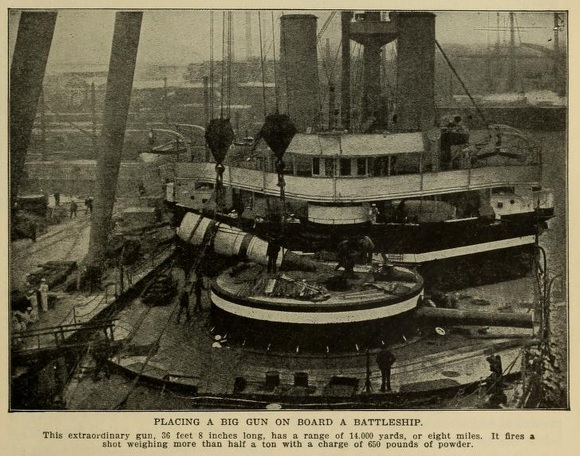

Since that time there has been a constant rivalry between the ship-builder and armorer on the one hand, and the gun, gunpowder and projectile manufacturer on the other hand. Every improvement in armor plate has been met by a further advance, either in the gun, the projectile, or the propelling charge of the gunpowder. An armor-maker would announce the production of a steel plate which no existing cannon could penetrate. Then the projectiles were made conical, and with a sharp point, having a fine temper, and the gun was rifled to give the projectile rotation and true flight, and the guns were made to load at the breech instead of the muzzle, adding greatly to the rapidity and facility of fire.

Another inventor then came forward with a method of hardening the surface of the plate, by a process bearing his name. A Harveyized plate is so hard that it cannot be scratched with a file or cut with a cold chisel. Nickel was put in the plate, adding ing still more to its hardness and toughness.

Then smokeless powder was produced, developing much greater energy than its black predecessor, and made to burn with accelerating combustion, and with it projectiles could be hurled with such velocity that the energy of their impact could not be resisted by the plate, and the gun had to be lengthened and strengthened forward to meet the new demands upon it. The limit in the weight of armor plate was soon reached. Twelve inches in thickness came to be about the maximum for the belt of the strongest warship, for she could not carry thicker and float. The projectile was still more improved, being made of the finest forged steel and tempered with great skill. Then came Kruppized plate, and the projectile was again turned aside or smashed upon its surface. Lastly a soft nose made of mild steel was placed on the point of the armor-piercing projectile, and the gunner could again laugh at the thickest Kruppized plate that could be carried by the battleship.

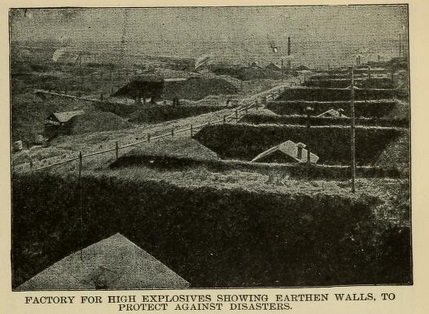

Contemporaneous with this work, the high-explosive manufacturer and inventor have been busy, but so burdened has been their work by popular misunderstandings of the nature of the high explosives, that they have had a much stronger barrier in the form of prejudice and ignorance to get through than has the gun manufacturer in keeping ahead of the armorer.

There was such a wholesale dread entertained by even rational investigators, and some inventors themselves, of high explosives, that they chose rather to theorize than to learn by experiment. It was believed by many that high explosives must of necessity be very ticklish, and that their sensitiveness must be in direct proportion to their explosive power. The word dynamite was sufficient to cause a person of average information to seek safety in flight from its vicinity. It was generally believed that if high explosives could only be thrown in any considerable quantity from guns they would destroy anything they might hit, or if they should strike in the water anywhere near a warship it would be sent to the bottom. But it was thought that guns must be constructed in some peculiar way, and a propelling means especially adapted to lessen the shock be employed for throwing some special kind of bomb, in order to get the dynamite out of the gun very gently.

Pneumatic dynamite-gun battery in San Francisco.

The most notorious of these freaks in ordnance is the so-called pneumatic dynamite gun, a battery of which guns was erected at Sandy Hook and protected at great expense, and a similar battery was put up at San Francisco. The expense of these outfits was enormous, and absolutely to no purpose whatever. Their range is limited to about a mile and a half. The projectile has no power of penetration whatever, and must necessarily go off on impact outside of an object, should the gunner be so lucky as to hit anything with it; but the angle of fire is so high, and the range so short, that the question of hitting an enemy's battleship with one of these weapons can be no longer seriously considered. A fleet of modern battleships could lie with perfect safety within close gunshot of these batteries and bombard them out of existence, and it would be impossible for the pneumatic guns to get a single shot within half a mile of any of the battleships.

Sandy Hook proof battery in 1900.

In 1899 Gen. A. K. Buffington, the Chief of Ordnance of the United States Army, determined to thoroughly investigate the subject of high explosives, and he arranged that the Ordnance Board, with headquarters at Sandy Hook Proving Ground, New Jersey, should carry out a line of experiments in such a thorough and efficient manner as to settle once for all what known high explosives were the most suitable for use in the service, and also to test thoroughly and without partiality, any and all new high explosives which might be submitted by different inventors and manufacturers, provided they appeared to offer sufficient merit to warrant investigation.

Maximite, which was adopted by the Government, satisfactorily stood every test to which it was subjected. It is very inexpensive of manufacture; has a fusion point below the temperature of boiling water; cannot be exploded from ignition, and, indeed, cannot be heated hot enough to explode, for it will boil away like water without exploding. It is, therefore, perfectly safe to melt over an open fire for filling projectiles, in the same manner that asphalt is melted in a street caldron. Should the material by any chance catch on fire, it would simply burn away like asphalt, without exploding.

When cast into shells, it not only solidifies into a dense, hard incomprehensible mass on cooling, but it expands and sets hard upon the walls of the projectile like sulphur, that is to say, in the same way as water does in freezing. Hiram Maxim, the inventor of this explosive, describes its effects as follows, and adds his opinions on the tendencies of modern warfare :

"When a shell filled with it strikes armor-plate, the Maximite does not shift a particle, and it is so insensitive that it not only stands the shock of penetration of the thickest armor-plate which the shell itself can go through, but it will not explode, even if the projectile breaks upon the plate.

"In one experiment a six-pounder projectile, filled with Maximite, fired against a thick plate, entered the plate about half its length and upset --- that is to say, shortened nearly two inches and burst open at the side, and some of the Maximite was forced through the aperture and the projectile rebounded from the plate about 200 feet and struck in the front of the gun from which it was fired, and all without exploding.

"Some lyddite shells --- that is to say, shells charged with picric acid, the high explosive adopted by the British Government, --- filled in the same way as was Maximite, into the same kind of projectiles and fired at a thin plate an inch and a half in thickness, all exploded on impact. So insensitive is this high explosive that melted cast iron may be poured upon a mass of it without causing an explosion. The writer has repeatedly made this experiment.

"When a projectile, however, charged with Maximite, is armed with a proper detonating fuse, such as that used in these experiments, the invention of a United States Army officer, it is exploded with such terrific violence that a 12-inch armor-piercing projectile was broken into at least 10,000 fragments; 7,000 were actually recovered. This armor-piercing projectile, weighing 1,000 pounds, was filled with seventy pounds of Maximite, armed with a fuse, and burned in the sand. After exploding, the sand was sifted to obtain the fragments.

"There were other high explosives tested with Maximite which also produced remarkable results. Had not Maximite been invented, the Ordnance Board would still have in its possession a high explosive developed by the Army Department itself, far superior to anything that has ever been employed in any other country, and the work of that Board for the last two years would have still been highly rewarded. Maximite has been adopted for the sole reason that it fulfills the largest number of the highest requirements sought for by the Ordnance Board."

Sir Hiram Maxim with a Maxim gun.

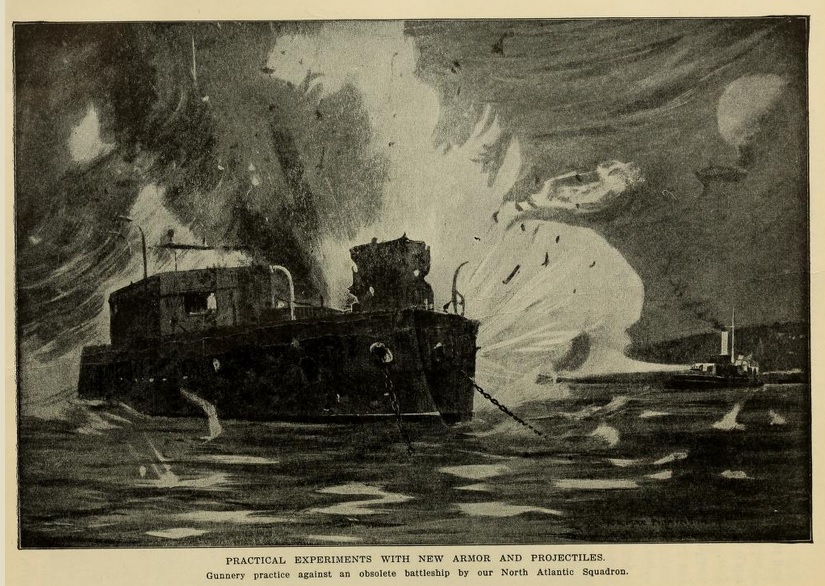

Not since the lesson taught by Ericsson's Monitor has anything been accomplished in military science more pregnant with meaning than these results at Sandy Hook. They have demonstrated that nothing whatever can be made to float with armor which will be capable of withstandmg the destructive effects of Maximite shells thrown from modern high-power guns, which are capable of penetrating the thickest Kruppized plates, to explode into a battleship.

Should the United States now become involved in war with any other great power, we should be able to throw these high explosive projectiles through the thickest armor of our enemies, to explode inside their warships, while they, in turn, would be able to penetrate our armor with solid shot, or, at least, with projectiles carrying no bursting charge whatever.

Mr. Maxim also says: "The moral taught by these new developments is that the ponderous battleships must go and be replaced by the small, swift torpedo boat or torpedo gunboat and cruiser, and practically unarmored, as no protection whatever can avail against such missiles. There must be no sacrifice of mobility for cumbersome armor.

"While Maximite places this government far in the lead of any other power in its weapons of offense and defense, it will, as well, save this government many hundreds of millions of dollars which should otherwise have been expended in the building of unwieldy battleships, for which other powers have squandered fabulous sums, and which must soon be recognized as obsolete. The competition between the great powers for naval and military supremacy is about as keen as it could be in an actual state of war, and the drain upon their resources is enormous, and the burden year by year is growing heavier. It is problematical whether England, France or Germany would prove the stronger in the event of war, and it is equally problematical which can longest endure the ever increasing drain upon its resources as a measure of insurance in the event of hostilities.

"And there is another problem --- and one of vast concern --- and it is whether these stupendous preparations are altogether wise on present lines; but no power dares to deviate too far from the main course pursued by the other powers for fear of making an irreparable, mistake, and so big battleship building still goes on, with a sort of half-awakened consciousness that these craft will prove a source of weakness rather than of strength.

"Along with the ponderous, armor-clad battleship, we have seen developed means for its destruction, so that to-day it holds no higher place with respect to invulnerability in face of these means, than did the wooden hulk of a half century ago in the face of the weapons then used. Indeed, it is probable that the modern battleship, costing five or six millions of dollars, will be in still greater danger of being sent to the bottom in a modern naval engagement than was the wooden craft of Nelson's time.

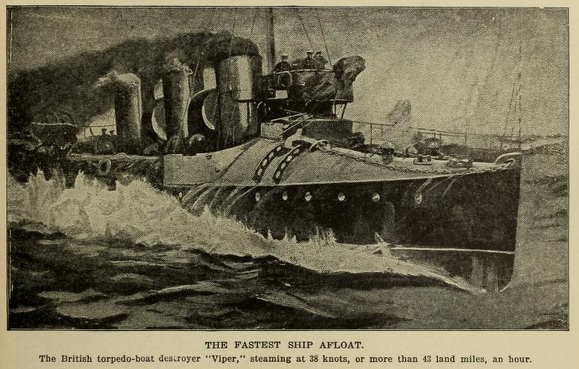

"Let us consider what will be the chief forces that will oppose the battleship and oppose one another in the next great naval engagement. First, there will be the torpedo boat and the torpedo boat destroyer, capable of traveling at a speed double that of the battleship, armed with Whitehead automobile torpedoes, which launched below the water lines will run beneath the surface as straight as an arrow to deal the battleship a fatal blow below its armored protection. There will also be the submarine boat, similarly armed, which has already shown itself capable of stealing upon the battleship wholly unobserved, to deal it a deadly blow, even in the glare of noon, as well as at the dead of night.

"And there will be another form of torpedo craft, armed with automobile torpedoes, which will run upon the surface of the water like an ordinary torpedo boat, but at railroad speed, and which will dive to a semi-submerged position when coming within the range of the enemy's guns. Half a dozen torpedoes will be launched by it in a moment, and the little boat will be endangered only by the huge vortexical gulf down which the battleship takes its plunge to the bottom of the sea.

"Now that a high explosive has been developed, which is capable of withstanding the shock of penetration of the hardest steel wall of the biggest armor-clad, to explode in vital parts, the battleship has another and most formidable antagonist. By means of this invention the destructiveness of the present high-power gun is enormously increased.

"There will be two systems of guns and projectiles employed --- the one the present quick-firing, high-power cannon, throwing armor-piercing projectiles carrying relatively small bursting charges of high explosives, to explode on the interior of the warship, or within the armor, to rip it from the sides. The other will be the torpedo gun, throwing aerial torpedoes carrying half a ton or more of high explosive at high velocity, to explode and crush the walls of the battleship or demolish its superstructure, or, if falling in the water, to crush in the sides below the armored belt. Each of these systems will have its advantages over the other, and will also have its disadvantages. While the large quantity of explosive carried in the aerial torpedo will be capable of working wide destruction when landing fairly on the mark, yet the quick-firing cannon, with equal range, and able to fire many times as fast, with projectiles capable of penetrating the strongest armor, to explode inside, will remain no mean rival to the torpedo gun, and any and all other forms of attack.

"The first and most important lesson which will be learned from the next great naval battle will be that armored protection will not protect, and the fight will soon be a duel between battleships at long range, aided by various forms of torpedo boats, and light unarmored cruisers, throwing high explosives ; and these latter will be the factors which will determine the fight. The heavy armorclad will be discredited, and then will be a wild scramble by the nations in the endeavor to make up for the lost time wasted on its construction, and light and very swift unprotected war vessels will be constructed, depending for their safety upon their speed, and upon their own ability to strike death-dealing blows. These are the true principles which must, sooner or later, be recognized.

"The British Government now proposes building still larger and heavier battleships and, of course, enormously more expensive. Within the next decade, and sooner, in the event of the great war, this will be learned by the British War Office to be a great mistake.

"The writer pointed out some years ago that the introduction of gunpowder was long opposed on grounds which, according to twentieth century ideas, are supremely ridiculous. To us moderns nothing could be more apparent than the superiority of firearms over bows and arrows as weapons of war. A few years hence, the present panorama of the nations will appear ludicrous, vying with one another for naval and military supremacy, and exhausting their treasuries in the construction of huge battleships, a dozen of which will be sunk by a torpedo fleet costing no more than one of them. Such battleship destroyers are now an accomplished fact, and lie under the eyes of all the world to-day, but are not seen. Their merits are told into ears that are as deaf as death. It is like knocking at the doors of an empty house for admission. Only the issue of a great naval battle can bring the torpedo fleet into proper recognition.

"When firearms were first introduced, the foot-soldier was clothed in armor, which was constantly increased in weight and thickness to resist improved weapons, until it became so ponderous and unwieldy as to sadly interfere with mobility. It was found impossible, however, for the soldier to carry armor thick enough to protect him against missiles hurled by gunpowder. As a result, all the armor was discarded. The modern war vessel has now entered upon a similar phase of its evolution, and for exactly the same reason that the soldier was obliged to discard his armor, so will armor have to be sacrificed in the coming war vessel, and the most practical means of defense will then be found to consist in the very means which serve best for offense."

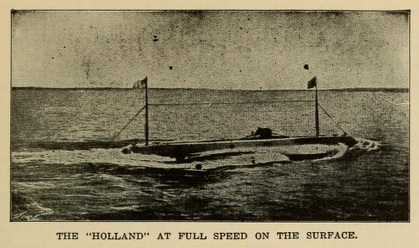

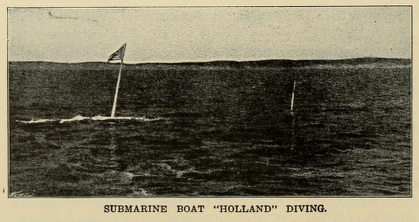

The naval authorities of most of the maritime powers have studied with great interest the progress of experiments in submarine craft. Inventors for years have been endeavoring to perfect vessels that could be submerged and still propelled and controlled with safety to their occupants. This series of investigations has been encouraged by the governments with some spirit of rivalry as to which country should first obtain such a practicable craft. In our own country the vessel known as the Holland, named for its inventor, has achieved remarkable success and has been adopted by the government as a worthy adjunct to our coast defense.

The vessel travels at fair speed on the surface, may be submerged for several hours without discomfort or danger to its crew, and can travel slowly under water, so that it may advance clandestinely upon an enemy without danger of discovery. For launching torpedoes against the side of a battleship without danger to the attacking party, such craft have every advantage. They have not been perfected yet to a degree that enables them to make long voyages, but the present success is sufficient to promise great improvements in the future.

The French experiments have been successfully achieved through the skill and genius of Gustave Zádé, an inventor of Toulon, who has built two interesting craft of which the latest, named for himself, is the most successful. This latter boat is 147 feet long and is propelled by electric motors with storage batteries. The hull is cigar-shaped, with very sharp ends, and the speed is eight-and-a-half knots an hour below, and fourteen knots above the surface. A crew of ten men is carried, with compressed air, stored in tanks, enough to last them while below. Torpedoes may be discharged from an opening in the bow of the boat. This vessel has been operated in deep and shallow water with remarkable success, and has made trips up to seventy miles without difficulty.

All of these submarine craft are operated on the same general principle, being sunk by admitting water to tanks provided for the purpose, and raised to the surface again by the buoyancy of these tanks when the water is pumped out.

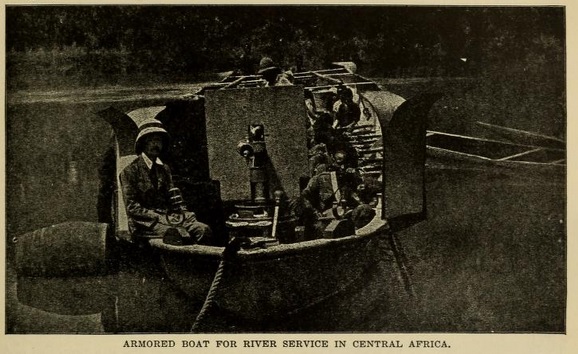

For warfare in the interior of uncivilized countries, the light-draft armed vessel also has been brought to a high degree of adaptability. The British in Africa use what they term an armored canoe, although the word "canoe" is a misnomer. It is a heavy steam launch, covered with boiler iron, and with shields to protect the men and the rapid-firing machine guns which it carries. Such a boat can penetrate the African jungles by way of the rivers and can assist in campaigns against savage tribes who could with difficulty be reached at all by the trails through the forests. The United States, like other powers, utilizes light-draft gunboats for service in the rivers and archipelagoes of the Asiatic coasts, and the Pacific islands where such service is needed. The rivers of China and Korea, at the time of native attacks on foreigners, have been the frequent scene of such operations.

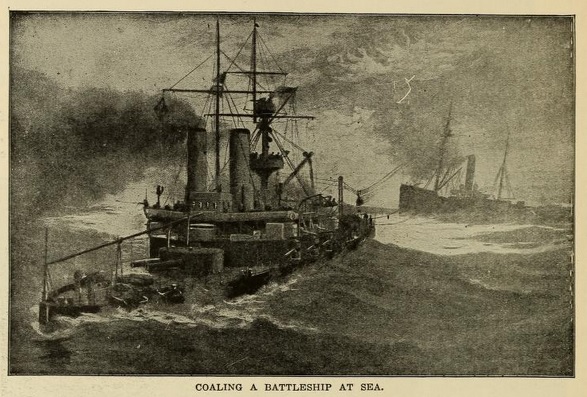

In order to still more facilitate the operations of warships at sea, a device has been invented by which the fighting craft may take coal without making port. Wire cables are strung between the masthead of the battleship and the collier, and upon these cables iron baskets are hauled back and forth until the coal is transferred. (This is an application of the trolley system by which ore and coal are conveyed from mines to cars for shipment, where valleys and hills intervene.) Experiments with this method of coaling have been made in the American navy and in the British navy, and in moderately rough weather forty tons per hour have been taken aboard a battleship from a collier. With practice it is believed that this speed can be greatly increased, and such embarrassments as hampered the American navy in the Caribbean during the late war will be eliminated.

The improvements in the appliances of warfare thus briefly indicated are typical of others upon which students of the arts of war are engaged. In these ante-millennium times, war is occasionally a necessary contingency, and when it comes we want the best tools we can get to fight with.

It is a crime for a nation not to be prepared for war, a crime against those who will be called upon to defend her in time of war. It is a crime for a nation not to be abreast of the times in arms and equipment. At best war is cruelty, but it is not only often a necessity but unavoidable, and, once engaged in, should be made as destructive as possible, in order that it may be brief as possible, thus minimizing the evil in the aggregate.

The approximate dates of the completion of the new battleships and cruisers of the United States were given by the Secretary of the Navy at the beginning of 1902 as follows : battleships : Maine, October, 1902 ; Missouri, March, 1903 ; Ohio, May, 1903 ; Virginia, May, 1904; Nebraska, July, 1904; Georgia, July, 1904; Rhode Island, July, 1904. Armored cruisers: Pennsylvania, January, 1904 ; West Virginia, February, 1904; California, August, 1904; Colorado, January, 1904; Maryland, February, 1904 ; South Dakota, August, 1904. With the completion of the above, the navy will have seventeen battleships and eight armored cruisers. The total number of warships of all kinds under construction at the same date was fifty-nine, including besides those mentioned, nine cruisers, four monitors, twenty-five torpedo boat destroyers, nine torpedo boats and seven submarines. In addition to these, the navy in commission at the same date included eleven men-of-war of the first rate, meaning above 8,000 tons ; fifteen of the second rate, or between 4,000 and 8,000 tons, and about eighty of less size, including monitors, cruisers, gun-boats and torpedo boats. The best calculations therefore credit the United States with being fourth among the powers in naval strength, surpassed only by England, France and Russia, and followed by Germany, Italy and Japan.

Hochseeflotte, 1917.