Little Sinners

Charles R. Gibson's Autobiography of an Electron

2014 January 6

Happy New Year! And how better to start the year than with a few words from the Edwardian equivalent of the immortal Qfwfq ?

Excerpts from

THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF AN ELECTRON

by Charles R. Gibson, F.R.S.E.

[London: Seeley (1911)]

The electron's words are in bold.

WHILE many scientific men now understand our place in the universe, we electrons are anxious that every person should know the very important part which we play in the workaday world. It was for this reason that my fellow-electrons urged me to write my own biography. My difficulty has been to find a scribe who would put down my story in the way I desired. The first man with whom I opened negotiations wished me to give him dates and names of which I knew nothing. And he asked such stupid questions about where I was born and who my parents were, as if I were flesh and blood.

I am pleased to say that my relationship with the scribe who has put down my story in the following pages has been of the most friendly description. Apart from a little tiff which we had at the outset, there has been no difference of opinion ...

... It is most amusing to me and my fellow-electrons to hear intelligent people speak of us as though we were new arrivals on this planet. Dear me ! We were here for countless ages before man put in an appearance. I wonder if any man can realise that we have been on the move ever since the foundations of this world were laid. It is man himself who is the new arrival.

It does seem strange to us that men should be so distinctly different from one another. We electrons are at a decided disadvantage, for we are all identical in every respect. I have no individual name ; it would serve no purpose. Even if you could see me, you could not distinguish me from any other electron.

I wonder sometimes if men appreciate the great advantage they have in possessing individual names ! I was impressed with this thought one fine summer morning. While I was riding on the back of a particle of gas in the atmosphere, I was carried through the open window of a nursery just as the under-nurse was putting the room in order. A little later there was some commotion in the nursery, for the young mother and her mother had come to see the twin daughters being bathed by the nurses. The grandmother happened to remark how very much alike the two little infants were. She said laughingly to the head nurse that she must be careful not to get the children mixed. But the big brother, aged five years, remarked that it would not matter really how much they were mixed until they got their names.

Sometimes I wish we electrons did differ from one another, so that we might each possess an individual name, but no doubt it is necessary for us all to be exactly alike ...

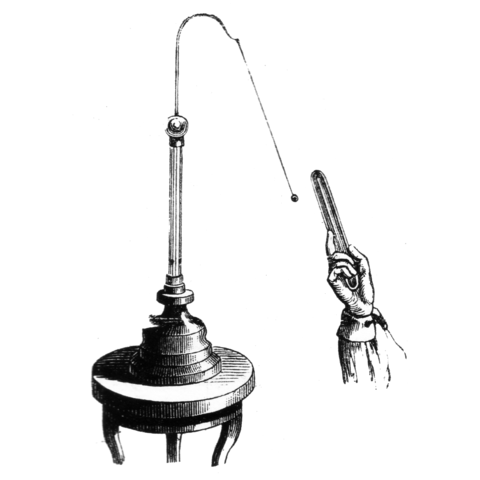

Long before man had discovered us, he caused us deliberately to do certain things. He was mystified by the results of his experiments, for he was not aware of our presence. A few of my fellow-electrons have rather hazy recollections of being disturbed while clinging to a piece of amber. They had been disturbed often before in a similar way, by being rubbed against a piece of woollen cloth, and the result had been always that a number of electrons let go their hold upon the cloth and crowded on to the amber. The overcrowding was uncomfortable, but it happened usually that the surplus electrons found some means of escape to the earth, where there is no need of excessive crowding.

On the occasion to which I refer, it so happened that the rubbing had been unusually vigorous and prolonged, so that the electrons were crowded on to the amber in great numbers. In their endeavour to escape they produced a strain or stress in the surrounding æther, and this caused a small piece of straw, which was lying within the disturbed area, to be forced towards the amber.

What attracted the attention of the electrons was that the man who was holding the piece of amber removed the clinging straw and replaced it exactly where it had been lying. In the meantime he had been handling the amber, and many of the crowded electrons had managed to make a bolt for the earth by way of the man's body. They did this so very quietly that the man did not feel any sensation. However, as soon as the amber was rubbed again, a similar crowd provided the same attractive property.

We electrons became impatient to hear what man would say of our work, for it was apparent that he had noticed the movements of the straw. You will hardly believe me when I tell you to what decision these wise men of the East came. They declared that, in rubbing the amber, it had received heat and life. As if life could be originated in any such simple manner !

You can picture our disappointment when we found that man was going to ignore our presence. Occasionally we were given opportunities of displaying our abilities in drawing light objects towards pieces of rubbed amber. But the funny thing was that man got hold of the stupid idea that this attractive property belonged to the amber instead of to us. If he had only tried pieces of sulphur, resin, or glass, he would have found that these substances would have acted just as well. You see it was not really the substance, but we electrons who were the active agents.

We had given up all hope of being discovered, when news came along that a learned man was on the hunt for us. He was crowding us on to all sorts of substances. He rubbed a piece of glass with some silk, and at first he was surprised greatly to see light objects jump towards the excited glass. Of course, we were not surprised in the very least. The only thing that amused us was to find that he was making out a list of the different substances which showed attractive properties when rubbed. He could not, evidently, get away from the idea that it was the substances themselves that became attractive.

We were sorry that the poor experimenter wasted so much time and energy in trying to crowd us on to a piece of metal rod. He rubbed and he rubbed that metal, but it would attract nothing, and I shall tell you the reason. You know that we electrons hate overcrowding ; indeed we always separate from one another as far as possible when there is no force pulling us together. We only crowded on to the amber because we could not help ourselves ; we had no way of escape, for amber is a substance we cannot pass through. But we have no difficulty whatever in making our way along a piece of metal, and as soon as the rubbing began, some electrons moved off the metal by way of the man's arm and body to make room for those being crowded on to the metal from the rubber. And so there never was any overcrowding, and consequently no straining of the æther.

But it was not long before we found that man had succeeded in cutting off our way of escape. He had attached a glass handle to the metal rod, and we were compelled to overcrowd upon the metal as we could not pass through the glass handle. Neighbouring light objects were attracted by the excited or "electrified" metal. Even this demonstration did not put man upon our track.

Perhaps I should explain in passing, that when a glass rod is rubbed with a silk handkerchief we crowd on to the silk, and not on to the glass. This leaves the glass rod short of electrons, and the æther is strained so that light objects are attracted. Man did notice that there was some difference between a piece of amber and a piece of glass when these were excited. What the difference was he could not imagine, but to distinguish the two different conditions he said that the amber was charged with "negative electricity" and the glass with "positive electricity".

From that time forward man became of special interest to us. We felt sure that sooner or later he was bound to recognise that we were at work behind the scenes. It seemed to us, however, that man was desperately slow in turning his attention towards us, and we tried to waken him up in a rather alarming fashion ...

... I must tell you of a surprise in which I took an active part. Some man thought he would separate a great crowd of us from our friends. Of course, he did not think really of us, but whatever he may have supposed he was doing, he succeeded in accumulating greater crowds of us together than he had done previously. He managed this by making simple machines to do the rubbing for him on a larger scale. The result was really too much for us ; we were kept crowding on to a sort of brass comb arrangement from which we could not escape, as the metal was attached to a glass support. Talk about overcrowding ! I had never experienced the like before, and I felt sure some catastrophe would happen. Suddenly there was a stampede, during which a great crowd of electrons forced their way across to a neighbouring object and thence to the earth.

I can assure you it was no joke getting through the air. We all tried to leap together, but some of the crowd were forced back upon us ; then bang forward we went again, back once more, and so on till we settled down to our normal condition. Of course all this surging to and fro occupied far less time than it takes to tell. Indeed, I could not tell you what a very small fraction of a second it took.

I wish you had seen the experimenter's surprise as we made this jump ! We caused such a bombardment in the air that there was a bright spark accompanied by a regular explosion. Some men ran away with the idea that electricity was a mysterious fire, which only showed itself when it mixed with the atmosphere.

Nothing delighted us more, after our own surprise was over, than to have a chance of repeating these explosions, to the alarm of the experimenters. But the best sport of all was to come, and when I heard of it I was so disappointed that I had not been one of the sporting party. It came about in the following way.

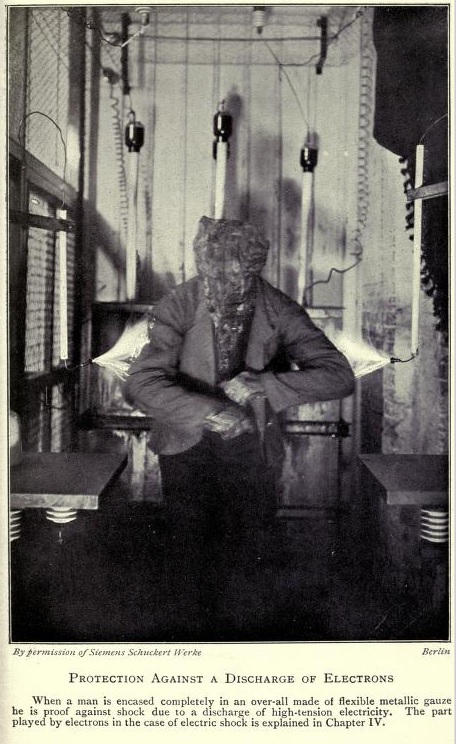

One learned man thought he had hit upon a good idea. He tried to crowd a tremendous number of us into some water contained in a glass jar. Without condescending to think of us, he crowded an enormous number of electrons from one of his rubbing machines along a piece of chain which led them into water. The overcrowding was appalling, for it was impossible to escape through the glass vessel.

Things had reached a terrible state, when the experimenter stopped the machine and put forward his hand to lift the chain out of the water. Now was the chance of escape, so the whole excited crowd made one wild rush to earth by way of the experimenter's body. The rapid surging to and fro of the crowd racked the man's muscles. I wish I had been there to see him jump ; they say it was something grand. You can imagine how the little sinners enjoyed the joke ; they knew they were safe, as man had no idea of their existence at that time.

Another man was foolhardy enough to try a similar experiment, and they say that his alarm was even greater ; indeed, he swore he would not take another shock even for the crown of France ! We were all eager to get opportunities of alarming man --- not that we wished him any harm, but we thought he might pay us a little more attention.

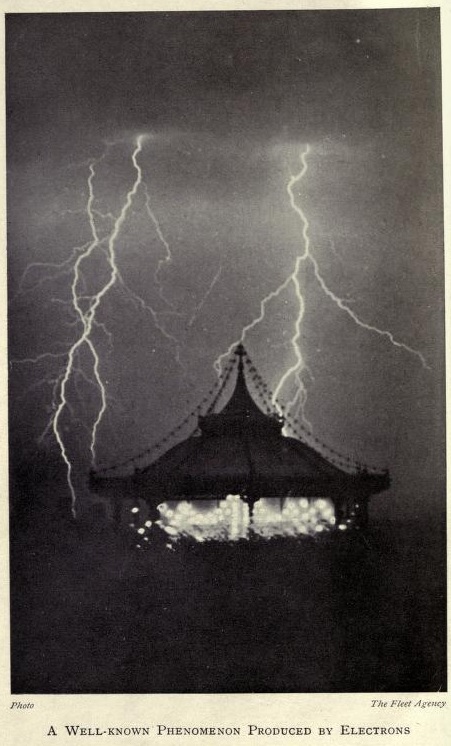

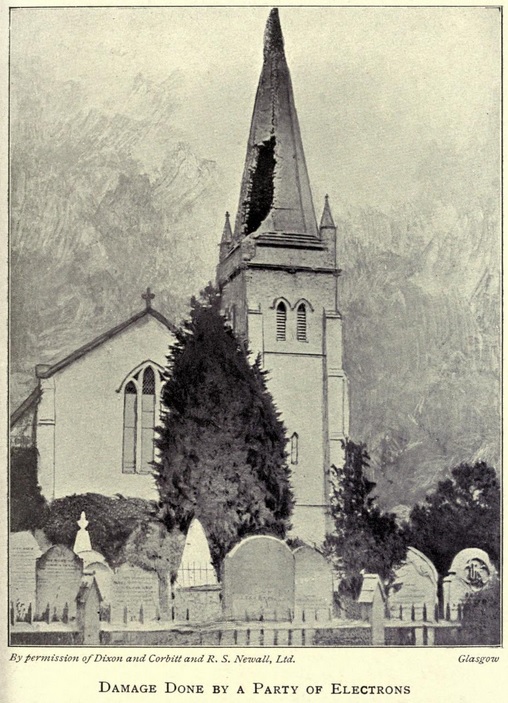

I remember one occasion upon which some of us were boasting of what we had done in the way of alarming men, whereupon one fellow-electron rather belittled our doings. He maintained that he had jumped all the way from a cloud to the earth, along with a crowd of other electrons. In doing so they had scared the inhabitants of a whole village, for they alighted upon the steeple of a church, and in their wild rush they played such havoc among the atoms composing the steeple that they did considerable outward damage to the great structure.

I may as well confess that we are not free agents in performing these gigantic jumps ; we are compelled to go with the crowd when things are in such a state of stress. We simply cannot hold on to the atoms of matter upon which we happen to be located. It is only under very considerable pressure that we can perform this class of jump, and I beg to assure you that we are perfectly helpless in those cases where we have been dashed upon some poor creature with a message of death.

Alas ! on one occasion I was one of a party who killed a very learned man. It was most distasteful to us ; we could not possibly prevent it. He had erected a long rod which extended up into the air, and terminated at the lower end in his laboratory. Some of us who were in the upper atmosphere were forced on to this iron rod, and from past experience we quite expected that we should be subjected to a sudden expulsion to earth. Indeed we were waiting for the experimenter to provide us with a means of escape, when suddenly he brought his head too near to the end of the rod, and in a moment we were dashed to earth through his body. We learned with deep regret that the poor man had been robbed of his life.

To turn to something of a happier nature, I shall proceed to tell you of some of my earliest recollections. Remember I shall be speaking of a time long before man existed even before this great planet was a solid ball.

... The whole, world then was a great ball of flaming gas. I have heard some fellow-electrons say that we were attached to a greater mass of incandescent gas before the beginning of this world, but I have no personal recollections of it. But one thing I do remember is a great upheaval which caused a large mass of gas to become detached from our habitation.

Without any warning a great myriad of our fellow-electrons were carried away on this smaller mass. At first this detached mass circled around our greater mass at very close quarters, but we soon found that our friends were being carried farther and farther away, until they are now circling around this solid planet at a comparatively great distance ...

When I have heard children say in fun that they wish they could visit the man in the moon, I have longed to go and see how it fares with those fellow-electrons who seem to be separated from us in such a permanent manner !

... But you will be interested in what happened before the moon's birth. I saw a crowd of electrons suddenly congregate together along with -- something else -- which man has not discovered.

Never mind the other part, but picture a number of electrons forming a little world of their own. There they went whirling around in a giddy dance. I saw these little worlds or "atoms" being formed all around, and I feel truly thankful now that I was not caught in the mad whirl, for these fellow-electrons have been kept hard at it ever since, imprisoned within a single atom. I have met a very few electrons who have escaped from within an atom, but I shall tell you about them later on.

The first thing I noticed was that each of the atoms had practically the same number of electrons in it. At that time I thought only in an abstract way, but since then I have learned that these were hydrogen atoms ; hydrogen being the lightest substance known to man. Exactly what happened next I cannot recollect, but my attention was attracted later to larger congregations of electrons forming other little worlds of their own. These atoms were, of course, heavier than the hydrogen atoms. I saw quite a variety of different systems, of which I thought then in an abstract fashion, but which I know now to be atoms of oxygen, nitrogen, carbon, iron, copper, and so on. While man has given the atoms these distinguishing names, you will understand that the incidents which I am relating took place long before there was any appearance of solidity about our planet ; these substances were all in a gaseous state.

After this, I recollect that there was a great envelope of water-vapour condensed around the planet. Some condensed into liquid water upon the surface of the globe, while part was suspended in the form of clouds. Some of my fellow-electrons acted as nuclei or foundations for the formation of the cloud particles. The water which condensed upon the earth settled down in the hollows, which had been produced previously by the immense pressure of the water-vapour envelope. We can hardly believe it is the same world !

You cannot imagine how strange it was to see the great oceans boiling and steaming; of course, they were fresh water then. I need hardly tell you that they have become salt only because the rivers have brought down sodium into them, and when these sodium atoms unite with chlorine atoms they form particles of common salt. I know all about this because we electrons play a very important part in all such combinations.

One very memorable recollection is that of life originating in the oceans. I wish I could let you into the secret of the origin of life, but, according to the Creator's plan, man must find out for himself. (Your guesses are all wide of the mark.)

By the way, perhaps I should explain why I have been selected to write this biography.

The first reason is that I am a free or detachable electron, and the second point in my favour is that I have had exceptional opportunities of seeing about me. I have heard men say that "lookers-on see most of the game," and as I have witnessed the gradual evolution of things, you will understand that I have views of my own.

A casual observer might think that things had deteriorated, for long ago there were immense monsters upon this planet, and these would put all modern creatures in the shade as far as size and strength are concerned. But one of the most interesting things to me has been to watch the evolution of man, and more especially the gradual development of his brain. Indeed, sometimes I have wished that I had happened to be an electron in the brain of a man ; but, on the other hand, my career would not have been of the varied kind which it has been ...

... Personally, I knew nothing about marching until quite recently. Indeed, none of my fellow-electrons seem to have had definite ideas of regular marches previous to last century. (That century is prominent in our history as well as in man's.) There is no doubt that before then we must have made more or less regular marches through the crust of the earth and elsewhere ; but for myself I have no such recollection previous to the following occasion.

The experience was not a very exciting one. I found myself passing along from atom to atom in a copper wire. But what was of special interest to us was that it became evident that these enforced marches were being deliberately controlled by man. Of course you will understand that man knew nothing of our existence at that time. All he knew was that when he placed a piece of zinc and a piece of copper in a chemical solution, there were certain effects produced in some mysterious fashion.

For instance, when he connected the top of the two metals in this chemical cell or " battery " by a piece of wire, he got what he described as an electric current. Now all that happened really was this. The chemical action in this battery which man had devised caused a rearrangement among the atoms composing the metals and the solution, with the result that we poor electrons had to rearrange our domiciles !

As an accumulation of electrons gathered on the zinc, some of us were forced along the connecting wire towards the copper. As long as the chemical action in the battery was kept up, so long were we kept on the march from the zinc to the copper by way of the wire.

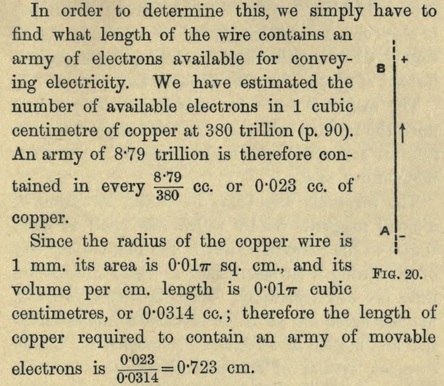

Man tried increasing the length of this wire bridge across which we had to pass, but we had no difficulty in making our way along. But you must not run away with the idea that we rush along the wire with lightning speed. Although we can fly through the æther at a prodigious speed, our progress from atom to atom in a wire is more like a snail-pace. As a matter of fact, our rate of march is much less than the walking pace of a man ; indeed it may be stated conveniently as so many yards per hour.

(Some people may find it difficult to believe that our rate of march is so very slow. Their front door is a good many yards away from their electric bell, but it does not take an hour, or any appreciable part of a minute, to summon the maid. The secret is that there is a whole regiment of us along the wire, and before one of us moves on to a neighbouring atom, another electron must move off that atom and on to its neighbour, and so on. In this way the electrons at the far end of the wire commence to move at practically the same moment as those near the battery.)

It has been a source of amusement to me to see people perfectly mystified by the fact that they can get no electric current unless they have a complete circuit. What else could they expect ? How could man march if he had no road to march on ?

You see, the reason for our march is that we wish to escape from the overcrowding on the zinc, and we are forced towards the copper. The atoms composing the wire are our stepping-stones, and if there is not a complete chain of atoms we are helpless. You have already heard how we can jump an air-space under very great pressure, but that condition does not exist in the present case. When we are disturbed by the chemical action of the battery, we should prefer to have a short-cut from the zinc to the copper, but if the only path man gives us is by way of a long wire, then we must be content to travel that road, in order to reach the copper ...

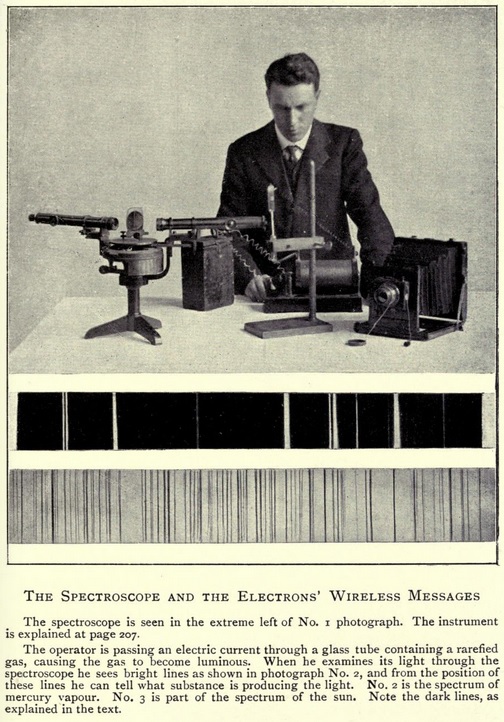

... After we had settled down to our ordinary duties, we got word that at last man had really detected us in a flame of gas. This seemed quite reasonable, for, as I shall relate to you in another chapter, we have a very lively time of it in a flame of gas. ...

... The next event was our christening, and this was not all plain sailing. Indeed, we have been rather annoyed with one name which some good friends persist in giving us. I refer to the name corpuscle, which we feel to be a sort of nickname, although it may have been suggested in all kindness.

It may be difficult for you to appreciate our dislike to this name, but it seems to us to savour too much of material things. It is not dignified ; you must remember we are not matter. We are delighted with what we prefer to call our real name -- electron -- for that speaks of electricity.

OUR RELATIONSHIP TO THE ATOMS

I am sorry that this part of my story must remain incomplete for the present. I am not free to tell you all I know ; you must try and get behind the scenes on your own account ... One thing I am at liberty to tell you is that my fellow-electrons who are locked up within the atoms are not without hope that they may gain their freedom once more at some future time. I know this first-hand, for I have met some fellow-electrons who have escaped from within an atom, but I shall delay telling you about these fellows till the succeeding chapter. My object in mentioning this fact now is to give you confidence in what I am about to say regarding the nature of the atom.

On one occasion I overheard a conversation between two men who were discussing the construction of matter. One remarked that the atoms were the "bricks of the universe", whereupon the other asked how the little "bricks" were cemented together. I wish that man could have seen a lump of matter as we see it. He would have been surprised to learn that the atoms never really touch each other. They are always surging to and fro, or vibrating, and it is this motion which constitutes the temperature of the body which they compose ...

First of all, perhaps, I should explain that the different kinds of atoms are simply congregations of different numbers of electrons. Of course there is the other part, of which I am forbidden to speak the part which man vaguely describes as "positive electricity". However, you may take it from me that while it is true that the main difference between an atom of gold and an atom of iron, or of oxygen, is in the number of electrons it contains, there is a very important difference in the arrangement of the electrons. You know that they form rings outside one another, all of which revolve at enormous speeds. The number of electrons in the different rings varies according to the kind of atom.

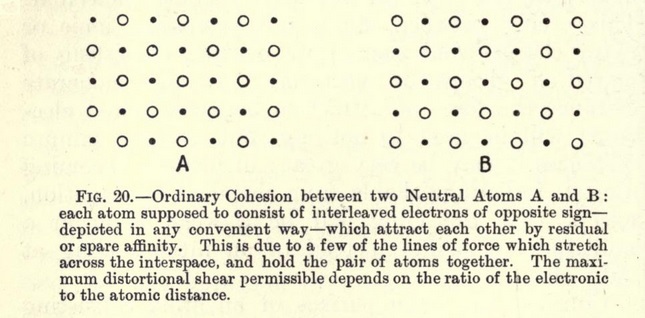

It is quite correct for man to speak of the atoms containing certain definite numbers of electrons, but I should like you to understand clearly that the exact number of electrons is not permanently fixed ; one or more electrons can slip off one atom and become attached to a neighbouring atom which happens to be capable of accepting it or them ... When man speaks of a chemical change having taken place in a substance, it is simply the electrons who have made a friendly interchange of detachable electrons, thereby causing a different assemblage of the same atoms ... It is the interchange of these few detachable electrons that causes one atom to attract another. In other words, it is the differently charged atoms which attract each other, just as man crowds a surplus of electrons on to one object and finds it attracted bodily towards another object having a deficiency of electrons ...

... We have formed only a limited number of atoms. I am not free to tell you exactly how many, for man has discovered only about eighty of these different congregations of electrons, each kind of which he calls an "element".

... I have heard a man ask how two different gases, hydrogen and oxygen, when united, should form a liquid, and not a gas. I wish you could see things as we see them. The atoms are neither gaseous, liquid, nor solid ; they are little worlds of revolving electrons.

From what I have told you of myself and my fellow-electrons, it must be apparent that we are of tremendous importance ... I have told you something of the part we played in building up this world how we not only form the atoms of matter, but also hold these bricks of the universe together. I have given you a rough sketch of the composition of these bricks.

You must have realised also that without us the whole universe would be in darkness. There would be no light, no heat, and consequently no life. Indeed, there could be no material existence without us.

Where would man be if we failed to perform our mission? He could not exist if we even neglected a few of our duties. Not only do we form the atoms of which his body is composed, also holding these together, but we produce all those chemical changes within his body which are absolutely necessary to maintain life. His very thoughts are dependent upon our activities !

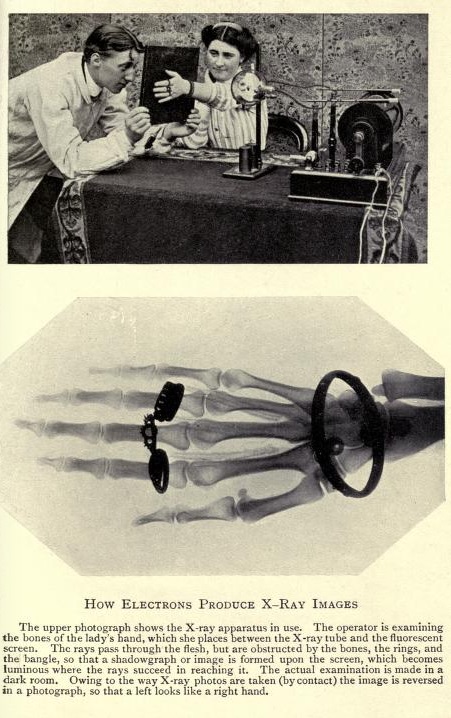

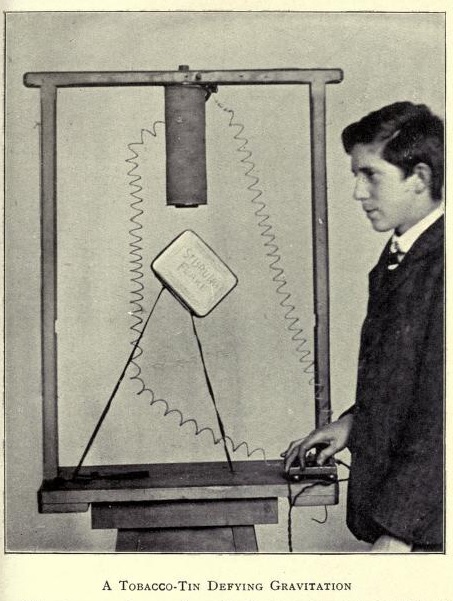

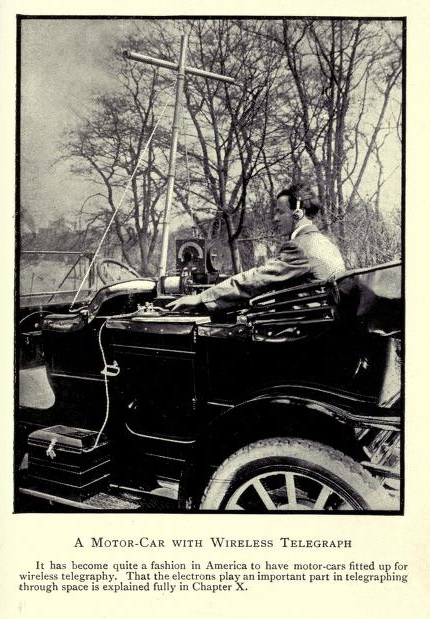

I have told you how we send man's messages across the earth, and how we transmit power from place to place. Also how we have enabled man to gain knowledge of the distant stars, and to examine the bones of his living body.

If man could cross-examine me or any of my fellows, I expect the first question would be "What are you electrons made of ?" But man must find this out for himself. The Creator has placed man in a world full of activity, and it is of intense interest to man to discover the meaning of all that lies around him. That is why I have been bound over by my fellows to tell you only so much of our history as man has discovered. But I am disclosing no secret when I admit that our very existence as electrons is dependent upon the æther.

If I can find another scribe to write a revised biography for me a few hundred years hence, I shall have a much more interesting tale to tell, for many of our doings, of which man knows nothing at present, will be secrets no longer by that time.