"In the month of February, 1861 ..." Photo by Christopher S. German, Springfield, 1861 February.

Oakland, California, 1898: Dr. Samuel Houston Melvin is dying. He writes a final testament:

"MEMORANDUM OF CERTAIN FACTS FOR INFORMATION OF THOSE WHO FOLLOW AFTER

"In the month of February, 1861, being at that time a resident of Springfield, Illinois, I called one evening at the residence of my friend Dr. John Todd. The doctor was an uncle of Mrs. Abraham Lincoln. While there Mr. Lincoln came in, bringing with him a well-filled satchel, remarking as he set it down that it contained his literary bureau. Mr. Lincoln remained some fifteen or twenty minutes, conversing mainly about the details of his prospective trip to Washington the following week, and told us of the arrangements agreed upon for the family to follow him a few days later. When about to leave he handed the grip above referred to to Mrs. Grimsley, the only daughter of Dr. Todd, who was then a widow but who subsequently became the wife of Rev. Dr. John H. Brown, a Presbyterian minister located in Springfield, remarking as he did so that he would leave the bureau in her charge; that if he ever returned to Springfield he would claim it, but if not she might make such disposition of its contents as she deemed proper.

"A tone of indescribable sadness was noted in the latter part of the sentence. Lincoln had shown me quite a number of letters a few days before, threatening his life, some predicting that he never would be inaugurated, and it was apparent to me that they were making an impression upon his mind, although he tried to laugh the matter off.

"About five years later the Nation was startled by the announcement of Lincoln's assassination. The corporation of Springfield selected twelve of its citizens to proceed at once to Washington and accompany the remains of the dead President back to his old home. I was one of that number ; and shall never forget the indescribable sadness manifested by millions of mourners along the route of travel of the funeral cortege as it wended its way westward over two thousand miles.

"A few evenings after his body was laid to rest, I again called upon my neighbors, the family of Dr. Todd. Scenes and incidents connected with the assassination and funeral of the dead President were discussed, and the remark made by Lincoln on his last visit to the house was referred to as indicating a presentiment that he would not return alive. This recalled the fact of his having left his so-called literary bureau, and his injunction as to its disposition. Mrs. Grimsley brought the grip from the place where it had been stored, and opened it with a view to examining its contents.

"Among them was found this manuscript, and attached to it by means of a piece of red tape was another of like character. They proved to be manuscripts of two lectures which he had prepared and delivered within a year prior to his election to the presidency, one at Jacksonville, Illinois, and a few days later at Decatur, Illinois; the other a little later at Cook's Hall, Springfield, Illinois, at which I was present. Mrs. Grimsley told me to select from the contents of the bureau any one of the manuscripts it contained, and supposing at that time that the two manuscripts belonged to the same lecture, I selected them. On subsequent examination I discovered that while they both treated upon the same subject (Inventions and Discoveries) they were separate lectures ; twenty-five years later I disposed of one of the manuscripts to Mr. Gunther of Chicago. The other it is my hope and desire shall remain in possession of my family and its descendants."

Actually, neither of the two Lincoln-autograph manuscripts once owned by Dr. Melvin seems to preserve a complete talk: both end so abruptly that they must be fragments. They were clearly meant for very different audiences.

The first fragment -- rather at odds with the entrenched modern view of Lincoln as one of America's least-religious presidents -- is a Protestant "Bible study", complete with chapter-and-verse citations. This is no doubt one reason that Dr. Melvin selected it for the edification of his descendants. When finally published at the centennial of Lincoln's birth, it first enjoyed great popularity and then, from the secular Twenties on, was largely forgotten. As the preface to a widely-distributed 1915 reprint comments, this "Lecture by our greatest American ... shows as clearly as any of his other writings how great was Lincoln's knowledge of the progress of mankind, particularly as related in the Bible, and it reveals also his debt to that Book of Books for inspiration and illustration, as well as his masterly use of pure English, largely gained through that study."

The second fragment presents a more familiar Honest Abe, the wise-cracking country lawyer (his jokes always sly enough that one is never quite sure what they mean), the hard-line opponent of slavery and imperialism who is also an advocate of compromise, perplexing friend and foe alike.

These two fragmentary speeches on "discovery and invention" neither outline the soon-to-be President's technological policy nor present an original system of back-woods philosophy. They do, however, provide insight into the mind of Nineteenth-Century America's quintessential autodidact. Lincoln taught himself by reading a very small number of books, but reading them very carefully and thoughtfully. His intellectual depth and almost superhuman detachment -- the character-traits which startled his contemporaries and provide the factual core at the heart of the Lincoln mythology -- are unmistakable when one considers that these were the subjects which occupied the rising politcian's mind between the debates with Douglas and the historic speech at Cooper Union!

US National Park Service

DISCOVERIES AND INVENTIONS, Part One: The Melvin Fragment.

Text from Discoveries

and Inventions: A Lecture by Abraham Lincoln Delivered in 1860.

[San Francisco: J. Howell, 1915].

Lincoln's words are in bold.

All creation is a mine, and every man a miner.

The whole earth, and all within it, upon it, and round about it, including himself, in his physical, moral, and intellectual nature, and his susceptibilities, are the infinitely various "leads" from which man, from the first, was to dig out his destiny.

In the beginning, the mine was unopened, and the miner stood naked, and knowledgeless, upon it.

Fishes, birds, beasts, and creeping things are not miners, but feeders and lodgers merely. Beavers build houses; but they build them in nowise differently, or better now, than they did, five thousand years ago. Ants and honey bees provide food for winter; but just in the same way they did, when Solomon referred the sluggard to them as patterns of prudence. Man is not the only animal who labors; but he is the only one who improves his workmanship. This improvement he effects by Discoveries and Inventions.

His first important discovery was the fact that he was naked ; and his first invention was the fig-leaf apron. This simple article, the apron, made of leaves, seems to have been the origin of clothing -- the one thing for which nearly half of the toil and care of the human race has ever since been expended.

The most important improvement ever made in connection with clothing, was the invention of spinning and weaving. The spinning jenny, and power loom, invented in modern times, though great improvements, do not, as inventions, rank with the ancient arts of spinning and weaving. Spinning and weaving brought into the department of clothing such abundance and variety of material ! Wool, the hair of several species of animals, hemp, flax, cotton, silk, and perhaps other articles, were all suited to it, affording garments not only adapted to wet and dry, heat and cold, but also susceptible of high degrees of ornamental finish.

Exactly when, or where, spinning and weaving originated is not known.

At the first interview of the Almighty with Adam and Eve, after the fall, He made "coats of skins, and clothed them" ( Genesis iii: 21). The Bible makes no other allusion to clothing, before the flood. Soon after the deluge, Noah's two sons covered him with a garment; but of what material the garment was made is not mentioned ( Genesis ix: 23).

Abraham mentions "thread" in such connection as to indicate that spinning and weaving were in use in his day ( Genesis xiv: 23), and soon after, reference to the art is frequently made. "Linen breeches" are mentioned ( Exodus xxviii: 42), and it is said "all the women that were wise-hearted did spin with their hands" ( Exodus xxxv: 25), and, "all the women whose heart stirred them up in wisdom spun goats' hair" ( Exodus xxxv: 26) . The work of the "weaver" is mentioned ( Exodus xxxv: 35). In the book of Job, a very old book, date not exactly known, the "weaver's shuttle" is mentioned [ Job vii: 6, citation added].

The above mention of "thread" by Abraham is the oldest recorded allusion to spinning and weaving; and it was made about two thousand years after the creation of man, and now, near four thousand years ago. Profane authors think these arts originated in Egypt; and this is not contradicted, or made improbable, by anything in the Bible; for the allusion of Abraham, mentioned, was not made until after he had sojourned in Egypt [ Genesis xii: 10ff, citation added].

The discovery of the properties of iron, and the making of iron tools, must have been among the earliest of important discoveries and inventions. We can scarcely conceive the possibility of making much of anything else, without the use of iron tools. Indeed, an iron hammer must have been very much needed to make the first iron hammer with. A stone probably served as a substitute.

How could the "gopher wood" for the Ark [ Genesis vi: 14, citation added] have been gotten out without an axe? It seems to me an axe, or a miracle, was indispensable.

Corresponding with the prime necessity for iron, we find at least one very early notice of it. Tubal-Cain was "an instructor of every artificer in brass and iron" ( Genesis iv: 22). Tubal-Cain was the seventh in descent from Adam ; and his birth was about one thousand years before the flood. After the flood, frequent mention is made of iron, and instruments made of iron. Thus "instrument of iron" at Numbers xxxv: 16 ; "bedstead of iron" at Deuteronomy iii : 11 ; "the iron furnace" at Deuteronomy iv: 20, and "iron tool" at Deuteronomy xxvii: 5.

At Deuteronomy xix: 5, very distinct mention of "the ax to cut down the tree" is made; and also at Deuteronomy viii: 9, the promised land is described as "a land whose stones are iron, and out of whose hills thou mayest dig brass." From the somewhat frequent mention of brass in connection with iron, it is not improbable that brass -- perhaps what we now call copper -- was used by the ancients for some of the same purposes as iron.

Transportation -- the removal of person and goods from place to place -- would be an early object, if not a necessity, with man. By his natural powers of locomotion, and without much assistance from discovery and invention, he could move himself about with considerable facility; and even, could carry small burthens with him. But very soon he would wish to lessen the labor, while he might, at the same time, extend, and expedite the business. For this object, wheel-carriages and water-crafts -- wagons and boats -- are the most important inventions.

The use of the wheel and axle has been so long known, that it is difficult, without reflection, to estimate it at its true value. The oldest recorded allusion to the wheel and axle is the mention of a "chariot" ( Genesis xli: 43). This was in Egypt, upon the occasion of Joseph being made governor by Pharaoh. It was about twenty -five hundred years after the creation of Adam. That the chariot then mentioned was a wheel-carriage drawn by animals is sufficiently evidenced by the mention of chariot wheels ( Exodus xiv: 25), and the mention of chariots in connection with horses in the same chapter, verses 9 and 23. So much, at present, for land transportation.

Now, as to transportation by water, I have concluded, without sufficient authority perhaps, to use the term "boat" as a general name for all water-craft. The boat is indispensable to navigation. It is not probable that the philosophical principle upon which the use of the boat primarily depends -- to-wit, the principle, that anything will float, which cannot sink without displacing more than its own weight of water -- was known, or even thought of, before the first boats were made. The sight of a crow standing on a piece of driftwood floating down the swollen current of a creek or river, might well enough suggest the specific idea to a savage, that he could himself get upon a log, or on two logs tied together, and somehow work his way to the opposite shore of the same stream. Such a suggestion, so taken, would be the birth of navigation; and such, not improbably, it really was. The leading idea was thus caught ; and whatever came afterwards, were but improvements upon, and auxiliaries to, it.

As man is a land animal, it might be expected he would learn to travel by land somewhat earlier than he would by water. Still the crossing of streams, somewhat too deep for wading, would be an early necessity with him. If we pass by the Ark, which may be regarded as belonging rather to the miraculous than to human invention, the first notice we have of water-craft is the mention of "ships" by Jacob ( Genesis xlix: 13). It is not till we reach the book of Isaiah that we meet with the mention of "oars" and "sails," [ Isaiah xxxiii: 21ff, citation added].

As man's food -- his first necessity -- was to be derived from the vegetation of the earth, it was natural that his first care should be directed to the assistance of that vegetation. And accordingly we find that, even before the fall, the man was put into the garden of Eden "to dress it, and to keep it," [ Genesis ii: 15, citation added]. And when afterwards, in consequence of the first transgression, labor was imposed on the race, as a penalty -- a curse -- we find the first born man -- the first heir of the curse -- was "a tiller of the ground," [ Genesis iv: 2, citation added]. This was the beginning of agriculture; and although, both in point of time, and of importance, it stands at the head of all branches of human industry, it has derived less direct advantage from Discovery and Invention, than almost any other.

The plow, of very early origin; and reaping- and threshing-machines, of modern invention, are, at this day, the principal improvements in agriculture. And even the oldest of these, the plow, could not have been conceived of, until a precedent conception had been caught, and put into practice -- I mean the conception, or idea, of substituting other forces in nature, for man's own muscular power. These other forces, as now used, are principally, the strength of animals, and the power of the wind, of running streams, and of steam.

Climbing upon the back of an animal, and making it carry us, might not occur very readily. I think the back of the camel would never have suggested it. It was, however, a matter of vast importance.

The earliest instance of it mentioned, is when "Abraham rose up early in the morning, and saddled his ass" ( Genesis xxii: 3), preparatory to sacrificing Isaac as a burnt-offering; but the allusion to the saddle indicates that riding had been in use some time; for it is quite probable they rode bare-backed awhile, at least, before they invented saddles.

The idea, being once conceived, of riding one species of animals, would soon be extended to others. Accordingly we find that when the servant of Abraham went in search of a wife for Isaac, he took ten camels with him; and,on his return trip, "Rebekah arose, and her damsels, and they rode upon the camels, and followed the man" ( Genesis xxiv: 61) .

The horse, too, as a riding animal, is mentioned early. The Red Sea being safely passed, Moses and the children of Israel sang to the Lord "the horse and his rider hath he thrown into the sea ( Exodus xv: 1).

Seeing that animals could bear man upon their backs, it would soon occur that they could also bear other burthens. Accordingly we find that Joseph's brethren, on their first visit to Egypt, "laded their asses with the corn, and departed thence" ( Genesis xlii: 26) .

Also it would occur that animals could be made to draw burthens after them, as well as to bear them upon their backs; and hence plows and chariots came into use early enough to be often mentioned in the books of Moses ( Deuteronomy xxii: 10; Genesis xli: 43; xlvi: 29; Exodus xiv: 25).

The revolutionary Halladay wind-mill, invented shortly before Lincoln's speech.

Photo taken at the American Wind Power Center and Museum by Billy Hathorn.

Of all the forces of nature, I should think the wind contains the largest amount of motive power -- that is, power to move things. Take any given space of the earth's surface -- for instance, Illinois; and all the power exerted by all the men, and beasts, and running-water, and steam, over and upon it, shall not equal the one hundredth part of what is exerted by the blowing of the wind over and upon the same space.

And yet it has not, so far in the world's history, become proportionably valuable as a motive power. It is applied extensively, and advantageously, to sail-vessels in navigation. Add to this a few wind-mills, and pumps, and you have about all. That, as yet, no very successful mode of controlling, and directing the wind, has been discovered; and that, naturally, it moves by fits and starts -- now so gently as to scarcely stir a leaf, and now so roughly as to level a forest -- doubtless have been the insurmountable difficulties. As yet, the wind is an untamed, and unharnessed force; and quite possibly one of the greatest discoveries hereafter to be made, will be the taming, and harnessing of it. That the difficulties of controlling this power are very great is quite evident by the fact that they have already been perceived, and struggled with more than three thousand years; for that power was applied to sail-vessels, at least as early as the time of the prophet Isaiah.

In speaking of running streams, as a motive power, I mean its application to mills and other machinery by means of the "water wheel" -- a thing now well known, and extensively used; but, of which, no mention is made in the Bible, though it is thought to have been in use among the Romans (Am. Ency., "Mill"). The language of the Saviour "Two women shall be grinding at the mill, etc." [ Matthew xxiv: 41, citation added] indicates that, even in the populous city of Jerusalem, at that day, mills were operated by hand -- having, as yet, had no other than human power applied to them.

The advantageous use of Steam-power is, unquestionably, a modern discovery. And yet, as much as two thousand years ago the power of steam was not only observed, but an ingenious toy was actually made and put in motion by it, at Alexandria in Egypt. What appears strange is, that neither the inventor of the toy, nor any one else, for so long a time afterwards, should perceive that steam would move useful machinery as well as a toy.

DISCOVERIES AND INVENTIONS, Part Two: The Gunther Fragment.

Text from the 1894 edition of the

The Complete Works of Abraham Lincoln .

[New York: Century, 1894]

[The opening paragraphs contain a double entendre which would have been clear to Lincoln's audience, but is now obscure: "Young America", beside its obvious generational meaning, was the name of a faction in the Democratic Party which advocated spreading the ideals of the United States around the world both by territorial conquest and by active support for revolutionary movements against European monarchies. Despite its ostensible radicalism, Young America was strongest in the South, and viewed abolitionism as a British plot to weaken the Union. One of its most prominent members was Lincoln's political arch-rival, Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas.]

We have all heard of Young America. He is the most current youth of the age. Some think him conceited and arrogant ; but has he not reason to entertain a rather extensive opinion of himself? Is he not the inventor and owner of the present, and sole hope of the future ?

Men and things, everywhere, are ministering unto him. Look at his apparel, and you shall see cotton fabrics from Manchester and Lowell ; flax linen from Ireland ; wool cloth from Spain ; silk from France ; furs from the arctic region ; with a buffalo-robe from the Rocky Mountains, as a general outsider. At his table, besides plain bread and meat made at home, are sugar from Louisiana, coffee and fruits from the tropics, salt from Turk's Island, fish from Newfoundland, tea from China, and spices from the Indies. The whale of the Pacific furnishes his candle-light, he has a diamond ring from Brazil, a gold watch from California, and a Spanish cigar from Havana. He not only has a present supply of all these, and much more; but thousands of hands are engaged in producing fresh supplies, and other thousands in bringing them to him.

The iron horse is panting and impatient to carry him everywhere in no time ; and the lightning stands ready harnessed to take and bring his tidings in a trifle less than no time. He owns a large part of the world, by right of possessing it, and all the rest by right of wanting it, and intending to have it.

As Plato [ Addison, Cato, V. i. 2] had for the immortality of the soul, so Young America has "a pleasing hope, a fond desire -- a longing after" territory. He has a great passion -- a perfect rage -- for the "new"; particularly new men for office, and the new earth mentioned in the Revelations, [ xxi: 1] in which, being no more sea, there must be about three times as much land as in the present.

He is a great friend of humanity ; and his desire for land is not selfish, but merely an impulse to extend the area of freedom. He is very anxious to fight for the liberation of enslaved nations and colonies, provided, always, they have land, and have not any liking for his interference. As to those who have no land, and would be glad of help from any quarter, he considers they can afford to wait a few hundred years longer.

[Lincoln means that the Mexican War, which he opposed as unwarranted aggression, was promoted as a "war of liberation" by politicians who supported slavery at home.]

In knowledge he is particularly rich. He knows all that can possibly be known; inclines to believe in spiritual rappings, and is the unquestioned inventor of "Manifest Destiny."

His horror is for all that is old, particularly ''Old Fogy" ; and if there be anything old which he can endorse, it is only old whisky and old tobacco.

Photo taken at Christ Church Cathedral Dublin by Andreas F. Borchert.

If the said Young America really is, as he claims to be, the owner of all present, it must be admitted that he has considerable advantage of Old Fogy. Take, for instance, the first of all fogies, Father Adam.

There he stood, a very perfect physical man, as poets and painters inform us; but he must have been very ignorant, and simple in his habits. He had had no sufficient time to learn much by observation, and he had no near neighbors to teach him anything. No part of his breakfast had been brought from the other side of the world; and it is quite probable he had no conception of the world having any other side. In all these things, it is very plain, he was no equal of Young America; the most that can be said is, that according to his chance he may have been quite as much of a man as his very self-complacent descendant. Little as was what he knew, let the youngster discard all he has learned from others, and then show, if he can, any advantage on his side.

In the way of land and live-stock, Adam was quite in the ascendant. He had dominion over all the earth, and all the living things upon and round about it. The land has been sadly divided out since; but never fret. Young America will re-annex it.

The great difference between Young America and Old Fogy is the result of discoveries, inventions, and improvements. These, in turn, are the result of observation, reflection, and experiment. For instance, it is quite certain that ever since water has been boiled in covered vessels, men have seen the lids of the vessels rise and fall a little, with a sort of fluttering motion, by force of the steam ; but so long as this was not specially observed, and reflected, and experimented upon, it came to nothing. At length, however, after many thousand years, some man observes this long-known effect of hot water lifting a pot-lid, and begins a train of reflection upon it. He says, ''Why, to be sure, the force that lifts the pot-lid will lift anything else which is no heavier than the pot-lid. And as man has much hard fighting to do, cannot this hot-water power be made to help him ?" He has become a little excited on the subject, and he fancies he hears a voice answering, ''Try me." He does try it; and the observation, reflection, and trial give to the world the control of that tremendous and now well-known agent called steam-power. This is not the actual history in detail, but the general principle.

But was this first inventor of the application of steam wiser or more ingenious than those who had gone before him ? Not at all. Had he not learned much of those, he never would have succeeded, probably never would have thought of making the attempt. To be fruitful in invention, it is indispensable to have a habit of observation and reflection ; and this habit our steam friend acquired, no doubt, from those who, to him, were old fogies.

But for the difference in habit of observation, why did Yankees almost instantly discover gold in California, which had been trodden upon and overlooked by Indians and Mexican greasers for centuries ?

[Here we see the often-mentioned Lincoln paradox: the opponent of slavery and defender of Mexican independence sounding more like one of his less-enlightened contemporaries!]

Gold-mines are not the only mines overlooked in the same way. There are more mines above the earth's surface than below it. All nature -- the whole world, material, moral, and intellectual -- is a mine; and in Adam's day it was a wholly unexplored mine. Now it was the destined work of Adam's race to develop, by discoveries, inventions, and improvements, the hidden treasures of this mine. But Adam had nothing to turn his attention to the work. If he should do anything in the way of inventions, he had first to invent the art of invention, the instance, at least, if not the habit, of observation and reflection. As might be expected, he seems not to have been a very observing man at first; for it appears he went about naked a considerable length of time before he ever noticed that obvious fact. But when he did observe it, the observation was not lost upon him ; for it immediately led to the first of all inventions of which we have any direct account -- the fig-leaf apron.

The inclination to exchange thoughts with one another is probably an original impulse of our nature. If I be in pain, I wish to let you know it, and to ask your sympathy and assistance ; and my pleasurable emotions also I wish to communicate to and share with you. But to carry on such commnnications, some instrumentality is indispensable. Accordingly, speech -- articulate sounds rattled off from the tongue -- was used by our first parents, and even by Adam before the creation of Eve. He gave names to the animals while she was still a bone in his side ; and he broke out quite volubly when she first stood before him, the best present of his Maker.

From this it would appear that speech was not an invention of man, but rather the direct gift of his Creator. But whether divine gift or invention, it is still plain that if a mode of communication had been left to invention, speech must have been the first, from the superior adaptation to the end of the organs of speech over every other means within the whole range of nature.

Of the organs of speech the tongue is the principal; and if we shall test it, we shall find the capacities of the tongue, in the utterance of articulate sounds, absolutely wonderful. You can count from one to one hundred quite distinctly in about forty seconds. In doing this two hundred and eighty-three distinct sounds or syllables are uttered, being seven to each second, and yet there should be enough difference between every two to be easily recognized by the ear of the hearer.

What other signs to represent things could possibly be produced so rapidly ? or, even if ready made, could be arranged so rapidly to express the sense ! Motions with the hands are no adequate substitute. Marks for the recognition of the eye, -- writing, -- although a wonderful auxiliary of speech, is no worthy substitute for it. In addition to the more slow and laborious process of getting up a communication in writing, the materials -- pen, ink, and paper -- are not always at hand. But one always has his tongue with him, and the breath of his life is the ever-ready material with which it works.

Speech, then, by enabling different individuals to interchange thoughts, and thereby to combine their powers of observation and reflection, greatly facilitates useful discoveries and inventions. What one observes, and would himself infer nothing from, he tells to another, and that other at once sees a valuable hint in it. A result is thus reached which neither alone would have arrived at.

And this reminds me of what I passed unnoticed before, that the very first invention was a joint operation, Eve having shared with Adam the getting up of the apron. And, indeed, judging from the fact that sewing has come down to our times as "woman's work,'' it is very probable she took the leading part -- he, perhaps, doing no more than to stand by and thread the needle. That proceeding may be reckoned as the mother of all "sewing-societies," and the first and most perfect "World's Fair," all inventions and all inventors then in the world being on the spot !

But speech alone, valuable as it ever has been and is, has not advanced the condition of the world much. This is abundantly evident when we look at the degraded condition of all those tribes of human creatures who have no considerable additional means of communicating thoughts. Writing, the art of communicating thoughts to the mind through the eye, is the great invention of the world. Great is the astonishing range of analysis and combination which necessarily underlies the most crude and general conception of it -- great, very great, in enabling us to converse with the dead, the absent, and the unborn, at all distances of time and space ; and great, not only in its direct benefits, but greatest help to all other inventions.

Suppose the art, with all conceptions of it, were this day lost to the world, how long, think you, would it be before Young America could get up the letter A with any adequate notion of using it to advantage?

The precise period at which writing was invented is not known, but it certainly was as early as the time of Moses ; from which we may safely infer that its inventors were very old fogies.

Webster, at the time of writing his dictionary, speaks of the English language as then consisting of seventy or eighty thousand words. If so, the language in which the five books of Moses were written must at that time, now thirty-three or -four hundred years ago, have consisted of at least one quarter as many, or twenty thousand.

[Lincoln is following Bishop Ussher's chronology, according to which Adam was created around 4000 BC and Moses lived around 1450 BC. If Adam had a vocabulary of size zero -- an underestimate, since the Biblical text has him giving names to all the animals and conversing with Eve -- a linear extrapolation backward from 1850 would indicate that a typical language in the time of Moses had at least thirty-five thousand words. How then did Lincoln arrive at the figure twenty-thousand? I suspect that in doing the calculation he mistakenly put down 1450, the number of years Moses lived before Christ (instead of 2550, the number of years he lived after the Creation), divided by 5800 (the approximate age of the world), and concluded that three-quarters of human history, rather than only a little more than half, must have taken place since Moses wrote the Pentateuch.]

When we remember that words are sounds merely, we shall conclude that the idea of representing those sounds by marks, so that whoever should at any time after see the marks would understand what sounds they meant, was a bold and ingenious conception, not likely to occur to one man in a million in the run of a thousand years. And when it did occur, a distinct mark for each word, giving twenty thousand different marks first to be learned, and afterward to be remembered, would follow as the second thought, and would present such a difficulty as would lead to the conclusion that the whole thing was impracticable.

But the necessity still would exist ; and we may readily suppose that the idea was conceived, and lost, and reproduced, and dropped, and taken up again and again, until at last the thought of dividing sounds into parts, and making a mark, not to represent a whole sound, but only a part of one, and then of combining those marks, not very many in number, upon principles of permutation, so as to represent any and all of the whole twenty thousand words, and even any additional number, was somehow conceived and pushed into practice. This was the invention of phonetic writing, as distinguished from the clumsy picture-writing of some of the nations. That it was difficult of conception and execution is apparent, as well by the foregoing reflection, as the fact that so many tribes of men have come down from Adam's time to our own without ever having possessed it. Its utility may be conceived by the reflection that to it we owe everything which distinguishes us from savages. Take it from us, and the Bible, all history, all science, all government, all commerce, and nearly all social intercourse go with it.

The great activity of the tongue in articulating sounds has already been mentioned, and it may be of some passing interest to notice the wonderful power of the eye in conveying ideas to the mind from writing. Take the same example of the numbers from one to one hundred written down, and you can run your eye over the list, and be assured that every number is in it, in about one half the time it would require to pronounce the words with the voice; and not only so, but you can in the same short time determine whether every word is spelled correctly, by which it is evident that every separate letter, amounting to eight hundred and sixty-four, has been recognized and reported to the mind within the incredibly short space of twenty seconds, or one third of a minute.

[This quite modern bandwidth calculation is fairly accurate, as the reader may easily verify!]

I have already intimated my opinion that in the world's history certain inventions and discoveries occurred of peculiar value, on account of their great efficiency in facilitating all other inventions and discoveries. Of these were the art of writing and of printing, the discovery of America, and the introduction of patent laws. The date of the first, as already stated, is unknown; but it certainly was as much as fifteen hundred years before the Christian era ; the second -- printing -- came in 1436, or nearly three thousand years after the first. The others followed more rapidly -- the discovery of America in 1492, and the first patent laws in 1624.

(Though not apposite to my present purpose, it is but justice to the fruitfulness of that period to mention two other important events -- the Lutheran Reformation in 1517, and, still earlier, the invention of negroes, or of the present mode of using them, in 1434!)

[In 1434 Gilianez, an explorer employed by Henry the Navigator, rounded Cape Bojador south of Morocco and disproved the myth that a terrible "Sea of Darkness" lay on the other side. This marked the beginning of Portuguese expansion in West Africa, and thus of the Atlantic slave-trade.]

But to return to the consideration of printing, it is plain that it is but the other half, and in reality the better half, of writing ; and that both together are but the assistants of speech in the communication of thoughts between man and man. When man was possessed of speech alone, the chances of invention, discovery, and improvement were very limited; but by the introduction of each of these they were greatly multiplied. When writing was invented, any important observation likely to lead to a discovery had at least a chance of being written down, and consequently a little chance of never being forgotten, and of being seen and reflected upon by a much greater number of persons; and thereby the chances of a valuable hint being caught proportionately augmented. By this means the observation of a single individual might lead to an important invention years, and even centuries, after he was dead. In one word, by means of writing, the seeds of invention were more permanently preserved and more widely sown.

And yet for three thousand years during which printing remained undiscovered after writing was in use, it was only a small portion of the people who could write, or read writing ; and consequently the field of invention, though much extended, still continued very limited.

At length printing came. It gave ten thousand copies of any written matter quite as cheaply as ten were given before ; and consequently a thousand minds were brought into the field where there was but one before. This was a great gain -- and history shows a great change corresponding to it -- in point of time. I will venture to consider it the true termination of that period called ''the dark ages." Discoveries, inventions, and improvements followed rapidly, and have been increasing their rapidity ever since.

The effects could not come all at once. It required time to bring them out; and they are still coming. The capacity to read could not be multiplied as fast as the means of reading. Spelling-books just began to go into the hands of the children, but the teachers were not very numerous or very competent, so that it is safe to infer they did not advance so speedily as they do nowadays. It is very probable -- almost certain -- that the great mass of men at that time were utterly unconscious that their condition or their minds were capable of improvement. They not only looked upon the educated few as superior beings, but they supposed themselves to be naturally incapable of rising to equality. To emancipate the mind from this false underestimate of itself is the great task which printing came into the world to perform. It is difficult for us now and here to conceive how strong this slavery of the mind was, and how long it did of necessity take to break its shackles, and to get a habit of freedom of thought established.

It is, in this connection, a curious fact that a new country is most favorable -- almost necessary -- to the emancipation of thought, and the consequent advancement of civilization and the arts. The human family originated, as is thought, somewhere in Asia, and have worked their way principally westward. Just now in civilization and the arts the people of Asia are entirely behind those of Europe ; those of the east of Europe behind those of the west of it ; while we, here, in America, think we discover, and invent, and improve faster than any of them. They may think this is arrogance; but they cannot deny that Russia has called on us to show her how to build steamboats and railroads, while in the older parts of Asia they scarcely know that such things as steamboats and railroads exist. In anciently inhabited countries, the dust of ages -- a real, downright old-fogyism -- seems to settle upon aud smother the intellects and energies of man. It is in this view that I have mentioned the discovery of America as an event greatly favoring and facilitating useful discoveries and inventions.

Next came the patent laws. These began in England in 1624, and in this country with the adoption of our Constitution. Before then any man [might] instantly use what another man had invented, so that the inventor had no special advantage from his invention. The patent system changed this, secured to the inventor for a limited time exclusive use of his inventions, and thereby added the fuel of interest to the fire of genius in the discovery and production of new and useful things.

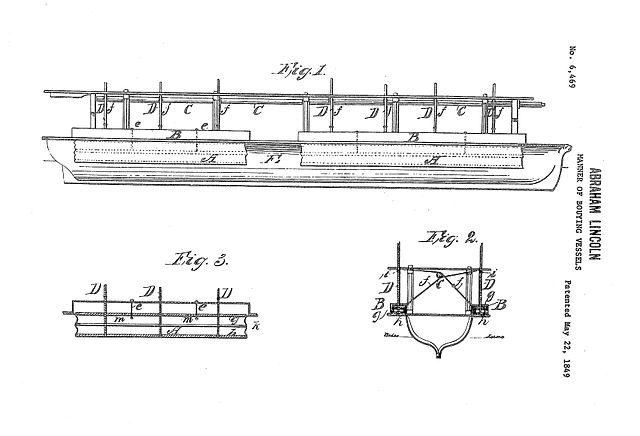

Just as Lincoln reaches a subject in which he had a great personal interest, the survivng text breaks off! Lincoln, like many frontiersmen, was a self-taught engineer, and a patent-holder, as we see from the illustration above.

One wonders what he would have made of the Internet Age. It is certainly remarkable that, speaking of "discoveries and inventions" at the very height of the Nineteenth Century industrial revolution, he has so little to say about "steam-power", and so much about the flow of information!

Abraham Lincoln, October 1859. Photo by Samuel M. Fassett.