William E. Lockhart: The Golden Jubilee Service, Westminster Abbey, June 21, 1887

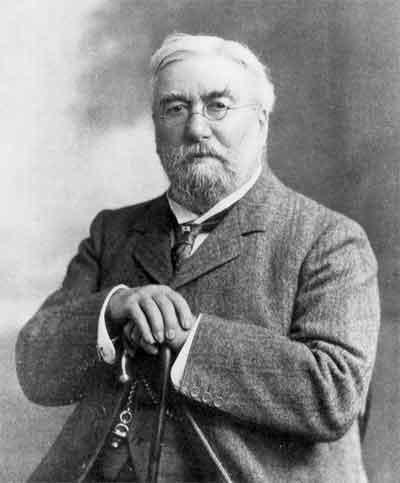

Lockyer was the co-discoverer of helium, and the founding editor of Nature. His words are in bold.

In loyalty the students of Nature in these islands are second to none, and their gladness at the happy completion of the fifty years' reign, and their respect for the fifty years' pure and beautiful life, are also, we believe, second to none. But the satisfaction which they feel on these grounds is tempered when they consider, as men of science must, all the conditions of the problem.

The fancy of poets and the necessity of historians have from time to time marked certain ages of the world's history and distinguished them from their fellows. The golden age of the past is now represented by the scientific age of the present. Long after the names of all men who have lived on this planet during the Queen's reign, with the exception of such a name as that of Darwin, are forgotten, when the name of Queen Victoria even has paled, it will be recognised that in the latter half of the nineteenth century a new era of the world's history commenced. Whatever progress there has been in the history of any nation during the last fifty years --- and this is truer of England than of any other country --- the progress has been mainly due to labourers in the field of pure science, and to the applications of the results obtained by them to the purposes of our daily and national life.

It is quite true that some men of Science take a pride in the fact that all this scientific work has been accomplished not only with the minimum of aid from the State, but without any sign of sympathy with it on the part of the powers that be.

We venture to doubt whether this pride is well founded.

It is a matter of fact, whatever the origin of the fact may be, that during the Queen's reign, since the death of the lamented Prince Consort, there has been an impassable gulf between the highest culture of the nation and royalty itself. The brain of the nation has been divorced from the head.

Literature and science, and we might almost add art, have no access to the throne. Our leaders in science, our leaders in letters, are personally unknown to Her Most Gracious Majesty. We do not venture to think for one moment that either Her Majesty or the leaders in question suffer from this condition of things ; but we believe it to be detrimental to the State, inasmuch as it must end by giving a perfectly false perspective ; and to the thoughtless the idea may rise that a great nation has nothing whatever to do either with literature, science or art --- that, in short, culture in its widest sense is a useless excrescence, and properly unrecognised by royalty on that account, while the true men of the nation are only those who wield the sword, or struggle for bishoprics or for place in some political party for pay and power.

The worst of such a state of things is that a view which is adopted in high quarters readily meets with general acceptance, and that even some of those who have done good service to the cause of learning are tempted to decry the studies by which their spurs have been won.

If literature is a "good thing to be left," as Sir George Trevelyan has told us ; if Mr. Morley, the politician, looks back with a half-contemptuous regret to the days when he occupied a "more humble sphere" as a leader of literature ; if students are recommended to cultivate research only "in the seed-sowing time of life ;" are not these things a proof that something is "rotten in the State," even in this Jubilee year ?

[The second Sir George Trevelyan, nephew of Lord Macaulay, combined a moderately successful career in Liberal politics with occasional forays into literature and history. Two of his works would perhaps interest readers of this blog: the essay Clio, comparing history to art and science; and a prize-winning science-fiction story about the later life of Napoleon in a world where the French had prevailed at Waterloo. I cannot find the source of his remark about leaving literature, but he seems never to have left it.

John Morley (later Lord Morley of Blackburn) had been a journalist, an acclaimed biographer of Eighteenth Century thinkers, and a leading Victorian intellectual before entering politics in the 1880s and becoming one of the most powerful Gladstonian Liberals.]

It surely is well that literature, science and art should be cultivated by men who are willing to lay aside vulgar ambition of wealth and rank, if only they may add the stock of knowledge and beauty which the world possesses. It surely is not well that no intellectual pre-eminence should condone for the lack of wealth or political place, and that as far as neglect can do it each scientific and literary man should be urged to leave work, the collective performance of which is nevertheless essential to the vitality of the nation.

It would seem that this view has some claims for consideration when we note what happens in other civilised countries. If we take Germany, or France, or Italy, or Austria, we find there that the men of science and literature are recognised as subjects who can do the State some service, and as such are freely welcomed into the councils of the Sovereign. With us it is a matter of course that every Lord Mayor shall, and every President of the Royal Society shall not, be a member of the Privy Council ; and a British Barnum may pass over a threshold which is denied to a Darwin, a Stokes or a Huxley.

Our own impression is that this treatment of men of culture does not depend upon the personal feelings of the noble woman who is now our Queen. We believe that it simply results from the ignorance of those by whom Her Majesty is, by an unfortunate necessity, for the most part surrounded.

The courtier class in England is --- and it is more its misfortune than its fault --- interested in few of those things upon which the greatness of a nation really depends.

Literary culture some of them may have obtained at the universities, but of science or of art, to say nothing of applied science and applied art, they for the most part know nothing ; and to bring the real leaders of England between themselves and the Queen's Majesty would be to commit a bêtise for which they would never be forgiven in their favourite coteries. No subject --- still less a courtier --- should be compelled to demonstrate his own insignificance.

That this is the real cause of the present condition of things which is giving rise to so many comments that we can no longer neglect them, is, we think, further evidenced by the arrangements that have been made for the Jubilee ceremonial in Westminster Abbey. The Lord Chamberlain and his staff, who are responsible for these arrangements, have, it is stated, invited only one Fellow of the Royal Society, as such, to be present in the Abbey ; while with regard to literature we believe not even this single exception has been made.

It may be an excellent thing for men of science like Professor Huxley, Professor Adams and Dr. Joule, and such a man of literature as Mr. Robert Browning, that they should not be required to attend at such a ceremonial, but it is bad for the ceremonial.

The same system has been applied to the Government officials themselves. Thus, the department responsible for science and art has, we believe, received four tickets, while thirty-five have, according to Mr. Plunket's statement in the House, been distributed among the lower clerks in the House of Commons. Her Gracious Majesty suffers when a ceremonial is rendered not only ridiculous but contemptible by such maladministration. England is not represented, but only England's paid officials and nobodies.

While we regret that there should be these notes of discord in the present condition of affairs, there can be no question that Her Majesty may be perfectly assured that the most cultured of her subjects are among the most loyal to her personally, and that they join with their fellow-subjects in many lands in hoping that Her Majesty may be long spared to reign over the magnificent Empire on which the sun never sets, and the members of which science in the future will link closer together than she has been able to do in the past.