SOURCE:

A Memoir of Zerah Colburn; Written by Himself

[Springfield, Mass.: Merriam, 1833]

Colburn's words are in bold.

CHAPTER II.

Zerah proceeds to New York, Philadelphia, and Washington. --- Returns to Norwich, Vermont. --- Starts once more for the South. --- Visits Boston. --- New Hampshire. --- Goes to New York and Washington. --- Richmond Theatre. --- Shipwreck. --- Mr. Colburn concludes to go to England.

The rejection of the proposals made in Boston, very speedily raised a prejudice against Mr. Colburn in that city. Some of the parties named in the Indenture were exceedingly displeased by his unwillingness to comply with their terms ; and he soon found that little prospect remained of promoting his object while within the scope of their influence. Accordingly, after many unavailing efforts to effect a change in the course which public feeling had taken, he departed for the South.

In New York and Philadelphia the reception his son met with was very flattering, the inhabitants signifying their approbation of his talent by liberal attendance and donations. In the latter city, a likeness of him was taken by Rembrandt Peale and placed in the gallery of the Museum.

Arriving at Washington, they found the Congress in session, and they spent some time in that city. However they met with no particular encouragement that appeared likely to alter their situation for the better, and they returned towards the North. At this period Mr. Colburn had money with him to the amount of five or six hundred dollars.

When they landed at the ferry from the Jersey side, Mr. C. proceeded to the tavern where he had put up during his former visit to New York. On going in, he inquired of the landlord if he could be accommodated there that night. The landlord replied in the affirmative.

They sat down in the bar-room and waited till about nine o'clock ; then he spoke to the host and said he should like to go to bed. The landlord started --- paused a moment, and then said : "Mr. Colburn, I have deceived you ; when you came in, I told you I could entertain you ; but my beds are all occupied."

"Very well," said Mr. C. "I can go somewhere else."

The landlord rejoined, "There is a room in the back part of the house, where I sometimes sleep when the other beds are full ; if you please, you may lodge there."

"Any place," said Mr. C., "is preferable to going out at this late hour." He took his trunk, and with Zerah followed the landlord through a back-yard surrounded with buildings, connected with the front of the house, up three flights of stairs, into a room where was a bed, set down the candle, and retired.

Zerah was soon in bed ; his father took off his boots and coat, blew out the candle, and lay down to think. Not feeling safe or satisfied, he rose, put on his coat, and descended, picking his way along to the bar-room. Informing the amazed landlord that he wished to speak with him alone, they went into an inner room, and Mr. C. began :

"When I first came into your house, you told me I could be accommodated with a bed ; during the evening I have seen very few guests, not half enough to fill your large house ; at bed time you have taken me up into that back-room, without lock or latch ; I know not what to think ; from the public papers you must know that I have a good deal of money with me, and it is my opinion you have a design upon my life. I shall not sleep in that room. If you can lodge me in the front of the house, well --- if not, I shall go to another tavern."

The host appeared completely at a stand ; twice or thrice he attempted to speak ; at length he made out to say : "You may have your choice of my rooms." Accordingly after bringing Zerah and the trunk out of the garret, the landlord conducted them into an apartment in the front of the house, furnished with two beds and a lock on the door ; he handed the key to Mr. Colburn, who said to him, "Now you may come at any hour in the night with as many as you please." He slept without disturbance.

The next day he called for his bill. The landlord inquired why he was going away ; on being told that it was because he could board cheaper in a private family than at a tavern, the man replied, "Only do not mention last night's adventure to any one, and you may stay here as long as you please at your own price." Mr. C. promised, and with his son remained there while in New York.

They afterwards went in the steam-boat up to Albany. It was on this passage, that a gentleman, by the name of Hopkins, taught Zerah the names and powers of the nine units, of which he had been previously ignorant. From Albany, they proceeded to Utica, receiving a patronage proportioned to the population of those places. At length Mr. Colburn directed his course towards Vermont.

[In Nineteenth Century arithmetic texts, the term "nine units" is quite frequent; it means simply the numbers 1 to 9. Colburn presumably has something else in mind, but it is unclear what.]

During this period that he had spent traveling through the States, he had very frequently been injured in his feelings by the remarks made by persons who labored under a wrong impression in regard to the indenture. When he arrived in Boston, he called upon the publishers of the public journals, in hopes that he might succeed in having the original paper, (which he always kept) printed, for the general information of the public. They all refused to admit the article into their columns, alleging as a reason, that it would be an indelible disgrace to the gentlemen concerned.

While on his journey to the South, many gentlemen of knowledge and experience had suggested the propriety of a voyage to England, on the ground that the wealthy and scientific in that country would be likely to afford patronage sufficient to answer every desirable purpose. This was a measure no way adapted to Mr. Colburn's feelings and wishes.

While he was in Boston, at this time, Elbridge Gerry, Esq. formerly Governor of Massachusetts, who was always a kind adviser, recommended the course, and offered letters of introduction. The time however was not yet come, for him to indulge the thought of such a separation from his family and country. He left Boston and went on to Norwich, Vermont, in April, 1811, where his family were transiently residing.

Had he at that time, in view of all his former trouble and vexations relative to his son, concluded to abandon the idea of obtaining property, and perhaps some honor on account of his boy's remarkable talent, it is a matter of belief, if not of certainty, that by returning to his farm, and laying out the money collected by exhibition in a prudent manner, he might have supported his family and brought them up in a respectable manner. Yet it was not surprising that the singular endowment of a member of his family in this manner, should produce an anxiety to secure its probable benefits ; while at the same time, a curiosity to seek in a proper use of means the object of the gift, might have had an influence ; moreover he felt himself injured in the Boston business, and being of a high spirit, he was unwilling to settle down at home, for he hoped such success would attend his efforts, as to convince the framers of the indenture that liberality was not confined to them, nor his welfare wholly dependent on their patronage.

After tarrying about a week at Norwich, he departed with his son, leaving about five hundred dollars with Mrs. Colburn, from which period he never saw his children. He went to Boston by way of Amherst, and was at length successful in getting the indenture printed. According to a previous arrangement, in May Mrs. Colburn joined her husband in Boston, and accompanied him to Concord, Exeter, and Portsmouth, New Hampshire. On the second of July, she took her final leave of her husband and returned to Cabot.

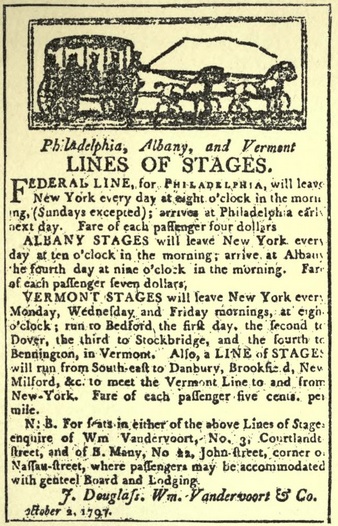

After her departure, Mr. C. pursued his way to Portland and soon made up his mind to try the effect of another journey to the South. They now visited Providence, New Haven, Hartford and the other places of note in Connecticut. Arriving at New York, they went on to Lancaster in Pennsylvania.

It was while on this road that they passed a pump which would probably have remained unknown and unnoticed in history, but for its handle, which by the sinking of the piston, was thrown up into the air.

A few weeks previous to their passing it, the stage, while traveling along in the evening, was suddenly stopped by the frightened driver, who declared, that an armed highwayman with shouldered musket, was waiting to intercept their passage. The passengers looked out and discovered the unconscious object of their alarm, standing in a truly threatening attitude, and even they thought he was moving towards them. The result of their council of war may be speedily told : one gentleman flung out his pocket book, another his purse, &c. &c. and the driver wheeling his horses rapidly round, they returned with all imaginable speed and related their wonderful preservation. The stolen pocket book and other articles were picked up the next day by some honest laborers, who little knew to what beneficent being they were indebted for their booty.

Another little circumstance may be related to show the erroneous views entertained by some in regard to the gift of Zerah. Being at Columbia, a little village on the Susquehanna, a woman sent a request to the tavern where he put up to have him come and see her ; he went, and after some preliminaries, she said : "About twenty years ago, I lost some silver spoons ; I suspect they were stolen. I want you to tell who has got them." It is needless to add, that being neither prophet nor conjurer he could not tell.

They arrived at Washington in the fall of 1811 ; --- at this time the Hon. Josiah Quincy was there, and Mr. Colburn called on him, hoping from the interest he had formerly taken, that he might then be able to point out some course that would render it advantageous for him to remain in America. However, Mr. Quincy did not feel himself in a situation to assume the responsibility of giving further advice.

Discouraged here, Mr. C. made up his mind to sail for England, and with that intention, engaged places in the northern stage. The night before he contemplated starting for Annapolis, Matthew Clay came in, being just arrived from the south. He had some conversation with Mr. Colburn that night, and finally dissuaded him from going to Boston until he had traveled more extensively in Virginia and the Carolinas. Yielding to his advice, and receiving letters from him to a number of the first people in Richmond, Mr. C. changed his course.

On their journey towards Richmond, a very striking comment was exhibited on the convenience of having good roads ; traveling along in the cloudy evening at a rapid rate, the stage went down a slight descent, and soon after reaching the level below was suddenly stopped. The driver applied the whip, but the horses could not start their load. After several fruitless attempts of this kind, the driver dismounted from his box and looked around to discover the impediment, but as the night was dark, and the stage unfurnished with lamps, he sought in vain. After a little deliberation it was deemed advisable that the horses should be liberated from the vehicle, and the passengers mount them to ride to the nearest stopping place. They went on about a mile before they reached a small house where the male and female travelers were accommodated as well as circumstances would admit, until morning. Then a stout yoke of oxen was sent down after the empty stage, and dragged it along. They found that the carriage had been thus forcibly detained by means of a stump, against which the axle-tree had been lodged, perhaps by some deviation from the road.

The next day they came to Fredericksburg. Here they were invited to stay a day or two by General Mercer. While at this place intelligence came of the burning of Richmond theatre. Among the victims of that awful conflagration were a number of the first people in the place to whom Mr. Colburn had letters of introduction. As he had never witnessed a dramatic exhibition, and but for General Mercer's invitation would have reached Richmond on the day that closed with that memorable night, he used to consider it a providential interposition that detained him in Fredericksburg: had he gone on, bethought it possible that some of the friends to whom Mr. Clay directed him would have taken him and his son to the theatre, in which case, he might have shared the mournful destiny of others.

When they arrived in the city, they visited the spot on which the theatre had stood, and beheld a striking lesson of the uncertainty of life, and the feeble tenure by which all earthly good is held. The place was lone and still ; so lately echoing with the cries of mirth --- still later with the frenzied shriek and wail of despairing, dying men, women, and children ; all was silent, and except foundation wall, and ashes, nothing was left to tell what life had glowed, what hearts had throbbed with joy, and soon with wildest grief, a few short days before.

By reason of this awful calamity Mr. Colburn's expectations of patronage in Richmond were cut off, and after a brief tarry among the bereaved and the suffering, they went on towards the South.

It appears by a letter written to his wife from New York City, dated October 14, 1811, that he had been strongly urged to remove his family to Charleston, in South Carolina, with ample promises of encouragement, but on account of the climate, he would not consent ; however he now concluded to visit that city in hopes of finding there what Providence withheld in Richmond. On his way he tarried a few days in Norfolk.

The actors connected with Richmond theatre, being thrown out of employment by the catastrophe stated above, had also started for Charleston ; and it so happened that they engaged their passage in the same vessel with Mr. C. and his son. They sailed from Norfolk at noon, January 12, 1812. As evening came on, the passengers began to prepare for spending it in the most jovial manner ; with cards, and songs, and merriment, they passed their time until nearly eleven. When they retired to rest, the snow was falling fast, and it was very dark.

At midnight the vessel struck in shoal water. Instantly the sleepers were awake, and soon learned the cause of their disturbance. The exuberance of their gaiety, which perhaps had not been wholly calmed by their short slumber, now met with a check perhaps equal to the terror and confusion of the burning theatre. The wind was high, the storm was severe, and the darkness so thick that on deck no object could be discerned, not even the hand held up before the eyes. The scene was truly terrific ; the vessel striking every minute with an awful shock ; no coast to be seen ; the commander unable to give directions for safety ; men vociferating ; women in agony, praying ; all combined exhibited a scene of sorrow better conceived than described.

Indeed there seemed to be no human probability of escape or of assistance. Some, under apprehension of the worst, went to the Steward, and swallowed as much strong drink as would suffice to render them insensible to the pain of drowning. One, a Captain in the Navy, declared if he ever set foot on dry land again, he would there abide. Another, a Frenchman, when first waked by the shock, learning the cause, was so completely paralyzed by fear, that beginning to dress, he put on his spectacles and sat down on the edge of his berth, with nothing over him, seemingly unconscious of every thing around.

Some of the men proposed to cut away the mast, as a probable expedient for safety --- to this the Captain objected with all his authority ; to this objection they were eventually indebted for their safety. Thus three or four hours passed heavily along, when by a providential shift of the wind, the vessel taking the advantage, filled her sails, and ran ashore, fast bedded in the sand about two roods below high water mark.

In the morning they landed on the beach, and traveling about a mile through the woods, discovered a house. From the inmates they learned that they were about thirty miles below Norfolk : that the place on which their vessel was cast was called False Cape. A few days were spent on this lonely beach under tents constructed with sails ; during which time the cargo was landed, and the shattered vessel abandoned.

They returned to Norfolk and, unsuccessful in this journey, Mr. Colburn began to think that his situation and prospects were not likely to be improved by a longer effort in his own country. The decided objections he had entertained to leaving his native country, and seeking his fortune in Europe, were strong in his mind ; but disappointed thus far in obtaining patronage to educate his son in a way that met his concurrence, he was very reluctantly led to a resolution to visit England.

In unison with this, while on his way to the North, he received letters of introduction, from the Hon. Rufus King, formerly Minister from this country to the British Court ; Elbridge Gerry, Esq., of Massachusetts; and others. Perhaps indeed it has fallen to the lot of very few, if any individuals, while attracting curiosity and notice, to receive at the same time so many flattering marks of kindness as the subject of this memoir ; and it is not unfrequently a sorrowful reflection to him, that after all the sympathy and benevolence shown by the liberal and scientific, certain unforeseen and unfortunate causes have prevented and still prevent his reaching and sustaining that distinguished place in the Mathematical Literature of the age, to which on account of the singular gift bestowed upon him, he seemed to be destined

Yet let him not repine, while realizing the higher obligations, honor, and usefulness of the station, which he now in the Providence of God, imperfectly and unworthily fills.