"We now add to these transformations all arbitrary shiftings of the space and time origin, and in this way construct a group of transformations obviously still dependent on the parameter c, which I designate by G(c)."

G(c) is then the set of

- all rotations of the space axes

- all scissor-like "boosts" involving the time axis

- all translations of the origin

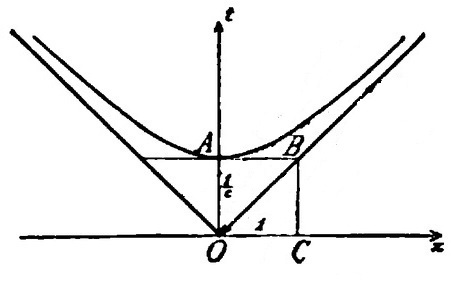

"If we now let c increase to infinity, 1/c thus converging to zero, we see from the figure described that the branch of the hyperbola always approaches closer to the x-axis, and the angle between the asymptotes widens into a straight angle."

The equation of the hyperbola is c² t² - x² = 1. The coordinates of point A are therefore (x=0, ct=1), or, equivalently, (x=0, t=1/c). The coordinates of point B are therefore (x=1, t=1/c), and those of point C are (x=1, t=0). As c becomes larger and larger, 1/c becomes smaller and smaller, so point A approaches the origin, point B approaches point C, and the hyperbola looks more and more like a straight line -- in fact, like the x-axis itself.

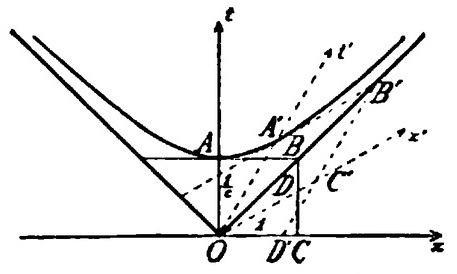

"At the limit the special transformation changes into one in which the t′-axis can have any upward direction and x′ steadily approaches nearer to x. "

Think about how x′ and t′ change as the distance OA goes to zero.

"In consequence of this, it is clear that the group G(c) in the limit for c=∞, (thus as the group G(∞)), becomes the complete group of Newton's mechanics."

Using Twentieth-Century language: Minkowski's metric space-time geometry becomes Newton's space-time fibre-bundle when c goes to infinity. Newtonian mechanics is then a limiting case of some more general kind of mechanics.

"Under these circumstances, and since G(c) is mathematically more intelligible than G(∞) ... "

More intelligible because it is finite. Although the situation is changing a bit in 1908, mathematicians remain uneasy about infinities.

"Under these circumstances, and since G(c) is mathematically more intelligible than G(∞), a mathematician in the free play of his imagination might well have had the idea that, after all, the phenomena of nature do not actually remain invariant for the group G(∞), but rather for a group G(c) with a c that is definite and finite but very large if taken in the ordinary units.

"Such an idea would have been an extraordinary triumph of pure mathematics. Now, although mathematics has here been caught napping, she still has the satisfaction that, owing to her happy antecedents, through senses made keen by their exercise in broad vistas, she is capable of grasping at once the far-reaching consequences of such a transformation of our conception of nature."

Einstein had taken classes from Minkowski at ETH. One can imagine how the (slightly) older mathematician must have felt in 1905: "Why didn't I think of that?" Perhaps he did think of it; he is supposed to have told Max Born that he had done so, not publishing because he wanted first to develop a fuller mathematical picture like the one in Raum und Zeit. But although Einstein found special relativity, and many people came close to finding it or perhaps would have found it eventually, only Minkowski understood just how amazing a thing had been found. Einstein's derivation involved (as in the title of his famous paper) "the electrodynamics of moving bodies"; his was a physicist's derivation, based on reasoning about light and motion. Minkowski, as a mathematician, recognised that this was needlessly restrictive and complicated; special relativity is not about physics, but about the geometry of space and time. It is about the very nature of reality.

Einstein was initially taken aback by the four-dimensional interpretation, but he quickly changed his mind (in part through the influence of Minkowski's friend David Hilbert) and made it the basis of his entire subsequent approach to physics. Without doing so, he would probably never have arrived at the far more abstract and original general theory of relativity a few years later, an astonishing achievement which no-one else but Hilbert came close to anticipating, and which remains strangely underappreciated even today.

"I shall now indicate what value of c will finally come into consideration. For c we shall substitute the term velocity of light in a vacuum. In order to avoid the terms 'space' and 'void' we can define this magnitude as the ratio between the electromagnetic and electrostatic units of electric quantity."

Electromagnetism has always been plagued by disagreements over units. Two once-popular systems, electromagnetic cgs and electrostatic cgs, employ rival units of charge which differ by a factor of the speed of light. There is a much deeper significance to this, however. The electrostatic system of units is based ultimately on Coulomb's law of the attraction between charges; the electromagnetic system on Ampere's law of the attraction between current-carrying wires. Each of these force laws contains an empirical, experimentally-measured constant in the other system of units. That the ratio of these two constants is the square of the speed of light was a surprise, and a major factor in the acceptance of Maxwell's theory. The use of electromagnetic methods to measure the speed of light was proposed jointly by Maxwell and the unjustly-forgotten Fleeming Jenkin in 1863; Minkowski may know that one of the best attempts to achieve this has just been made at the US Bureau of Standards.

"The existence of the invariance of natural laws for the group G(c) under consideration would now be derived as follows:

"From the totality of natural phenomena we can derive with ever increasing exactitude by successively closer and closer approximations, a system of reference x, y, z, and t, space and time, in terms of which these phenomena are then represented according to definite laws. But this system of reference is by no means uniquely determined thereby. It is still possible to change this system of reference at will, corresponding to the transformations of the above mentioned group G(c), without changing thereby the expression of natural laws.

"For example, according to the described figure, we can also call t′ the time, but then in connection with it we must necessarily define space by the manifold of the three parameters x′ y, z, in which case physical laws would be expressed in terms of x′, y, z, t′, exactly the same as in terms of x, y, z, t. According to this there would be in the world not that particular space but an infinite number of spaces, just as there is an infinite number of planes in three-dimensional space.

"Three-dimensional geometry becomes a chapter of four-dimensional physics. You now understand why I said at the outset that space and time are to fade away into mere shadows and that only a world-in-itself will exist."

Next: Part 2 -- Mathematics into Physics

Graphic by Miss MJ