PART 3B: Minkowski's words are in boldface.

is the condition that the vectors with the components x, y, z, t and x1, y1, z1, t1 are normal to each other."

Minkowski is defining the concept of "normal" (i.e. perpendicular) vectors in space-time. Vectors are considered perpendicular when the sum of the products of their components adds up to zero, that is, when their "inner product" is zero. It is easy to show that the inner product so defined is equal to the magnitude of the first vector times the magnitude of the second times the cosine of the angle between. When the vectors are perpendicular, the cosine is zero.

In three dimensions, it is intuitively obvious that any surface has a "normal" direction perpendicular to all the vectors tangent to the surface. In higher-dimensional spaces, there is no longer a single unique normal. (To see this, consider: in three dimensions, the up-down axis is perpendicular to the floor. If there is a fourth dimension, it, too, is perpendicular to the floor.) So a formal definition of orthogonality as the vanishing of the inner product is necessary.

However, Minkowski chooses what in Euclidean geometry would be considered an incorrect definition of orthogonality: the formula

has minus signs in it.

He justifies this by noting that tangents of the "interhyperbolas" are then perpendicular to the radii of a unit sphere in three dimensions (think about a hyperboloid of one sheet and a unit circle around the origin in ordinary geometry). A better justification, which he has in fact already discussed with colleagues at Göttingen, would be to assume that the geometry of space-time is not Euclidean, and that points at equal four-dimensional distance from O lie not on a (hyper)sphere but on an (hyper)hyperboloid.

"The unit measures for the scalars [in modern language, magnitudes] of vectors of different directions are to be so determined that the scalar 1 shall always be given to a space-like vector from O to −F=1, and 1/c to a time-like vector from O to F=1, t > 0.

"If we now consider the world-line of a substance-point passing through a world-point P (x, y, z, t), the scalar

accordingly then corresponds to the differential time-like vector dx, dy, dz, dt in passing along the line."

The world-line is a curve in four dimensions. The microscopic element dτ is a tiny vector pointing along the curve. With the non-Euclidean hyperbolic distance metric, the length of this vector is given by the formula.

(Carus's translation of the rest of this section is not very good, and I have made a number of changes.)

"The integral ∫dτ = τ of this quantity on the world-line measured from any fixed initial point P0 to a variable terminal point P, we call the proper time of the substance-point at P."

"Proper" (eigen) meaning "own", something proper to the substance-point itself. "Time" because the vector is time-like. The axis along which it points is the time axis in the frame where the substance-point is at rest. If the particle is moving irregularly, the direction of this instantaneously tangent axis may be continually changing, but it can always be found.

"On the world-line we consider x, y, z, t (the components

of the vector OP) as functions of the proper time τ and designate

their first derivatives with respect to τ by

![]() ,

the second derivatives with respect to τ by

,

the second derivatives with respect to τ by

![]() .

We give names to the vectors formed

from these: the derivative of the vector OP with respect to τ we call

the velocity vector at P, and the derivative of this velocity-vector with

respect to τ we call the acceleration-vector at P."

.

We give names to the vectors formed

from these: the derivative of the vector OP with respect to τ we call

the velocity vector at P, and the derivative of this velocity-vector with

respect to τ we call the acceleration-vector at P."

Whereas ordinary velocity, i.e. the rate at which position changes with time, depends on the observer's choice of a time axis, the special velocity defined here using the proper time is an intrinsic property of the world-line itself.

"Then the relations hold:

that is, the velocity-vector is the time-like vector in the direction of world-line at P of unit length and the acceleration-vector at P is normal to the velocity-vector at P, therefore certainly a space-like vector."

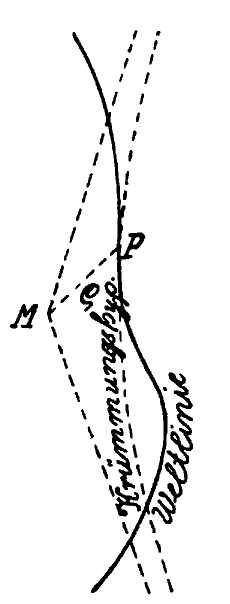

"Now there exists, as is easily seen, a definite hyperbola branch which has three infinitely-close points in common with the world-line at P and whose asymptotes are generators of a past and future cone (see Fig. 3)."

This hyperbola is a sort of local "best fit" hyperbola to the curve.

"Let this hyperbola branch be called the hyperbola of curvature at P. If M is the center of this hyperbola, we are here concerned with an interhyperbola with its center at M."

An interhyperbola (i. e. hyperbola in the "faster than light" region between the cones) because, as seen in the figure, its asymptotes run in the same time-like direction as the world-curve.

"Let ρ be the length of the vector MP, then we find the acceleration-vector at P to be the vector in the direction MP of length c²/ρ."

This is similar to the way that acceleration and circular radius of curvature are related in everyday physics -- think of a car going around a tight bend, that is, a place with a small radius of curvature, versus one travelling on an almost straight highway (a road with large radius of curvature).

"If

![]() are all zero, then the hyperbola of curvature reduces to the straight line

touching the world-line at P, and ρ is to

be put equal to ∞."

are all zero, then the hyperbola of curvature reduces to the straight line

touching the world-line at P, and ρ is to

be put equal to ∞."

This is the hyperbolic analogue of a circle with infinite radius reducing to a straight line.

TIME AND SPACE, by Hermann Minkowski