This week we present excerpts from an 1894 science-fiction novel remembered mainly for its author: real-estate and hotel magnate John Jacob Astor IV, in his day quite possibly the richest man in the world. A Journey in Other Worlds is "hard sf", full of technical details in the manner of Jules Verne; it is also a utopian novel of the perfect future (as imagined by a white American capitalist with fairly conventional political views) and the sometimes tedious manifesto of a then widespread, now almost extinct, form of mystical Christianity. Although Astor had inherited an immense fortune, he was gifted and intelligent, an inventor as well as a businessman. Like many Americans of his generation, he was patriotic to the point of jingoism, serving with distinction in the Spanish-American War, and his racial views, mild and unremarkable for the era, seem shocking today. It was his social life, featuring divorce and remarriage, that scandalised and fascinated his contemporaries. Something of an artist, he dabbled in acting as well in literature. A Journey in Other Worlds is not on a par with the novels of Wells or Bellamy, but it is better written than many of the futuristic fantasies and "Edisonades" which proliferated at the turn of the century.

And of course one cannot read Astor's account of an imagined space-voyage to the gates of Death without thinking of another, mythically far more resonant, voyage on which he and his pregnant wife were passengers ...

Mr. Astor with the second Mrs. Astor

Excerpts from

A JOURNEY IN OTHER WORLDS:

A Romance of the Future by John Jacob Astor

[New York: Appleton, 1894]

Astor's words are in bold.

"Come in!" sounded a voice, as Dr. Cortlandt and Dick Ayrault tapped at the door of the president of the company's private office on the morning of the 21st of June, A. D. 2000. Col. Bearwarden sat at his capacious desk, the shadows passing over his face as April clouds flit across the sun. He was a handsome man, and young for the important post he filled, being scarcely forty, a graduate of West Point, with great executive ability, and a wonderful engineer.

"Sit down, chappies," said he ; "we have still a half hour before I begin to read the report I am to make to the stockholders and representatives of all the governments, which is now ready. I know you smoke," passing a box of Havanas to the professor.

Prof. Cortlandt, LL. D., United States Government expert, appointed to examine the company's calculations, was about fifty, with a high forehead, greyish hair, and quick, grey eyes, a geologist and astronomer, and altogether as able a man, in his own way, as Col. Bearwarden in his. Richard Ayrault, a large stockholder and one of the honorary vice-presidents in the company, was about thirty, a university man, by nature a scientist, and engaged to one of the prettiest society girls, who was then a student at Vassar, in the beautiful town of Poughkeepsie.

"Knowing the way you carry things in your mind, and the difficulty of rattling you," said Cortlandt, "we have dropped in on our way to hear the speech that I would not miss for a fortune. Let us know if we bother you."

"Impossible, dear boy," replied the president genially. "Since I survived your official investigations, I think I deserve some of your attention informally."

"Here are my final examinations," said Cortlandt, handing Bearwarden a roll of papers. "I have been over all your figures, and testify to their accuracy in the appendix I have added."

So they sat and chatted about the enterprise that interested Cortlandt and Ayrault almost as much as Bearwarden himself. As the clock struck eleven, the president of the company put on his hat, and, saying au revoir to his friends, crossed the street to the Opera House, in which he was to read a report that would be copied in all the great journals and heard over thousands of miles of wire in every part of the globe.

When he arrived, the vast building was already filled with a distinguished company, representing the greatest intelligence, wealth, and powers of the world. Bearwarden went in by the stage entrance, exchanging greetings as he did so with officers of the company and directors who had come to hear him. Cortlandt and Ayrault entered by the regular door, the former going to the Government representatives' box, the latter to join his fiancée, Sylvia Preston, who was there with her mother.

Bearwarden had a roll of manuscript at hand, but so well did he know his speech that he scarcely glanced at it. After being introduced by the chairman of the meeting, and seeing that his audience was all attention, he began, holding himself erect, his clear, powerful voice making every part of the building ring.

"To the Bondholders and Stockholders of the Terrestrial Axis Straightening Company and Representatives of Earthly Governments.

"Gentlemen:

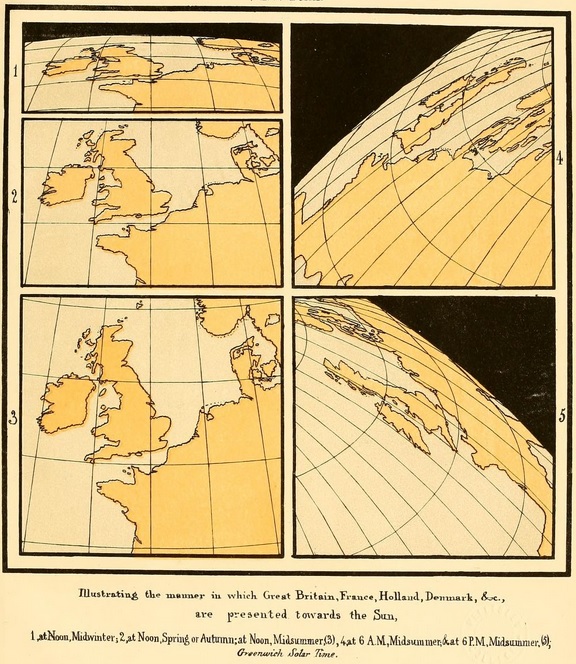

"You know that the objects of this company are, to straighten the axis of the earth, to combine the extreme heat of summer with the intense cold of winter and produce a uniform temperature for each degree of latitude the year round. At present the earth's axis, that is, the line passing through its centre and the two poles, is inclined to the ecliptic about twenty-three and a half degrees. Our summer is produced by the northern hemisphere's leaning at that angle towards the sun, and our winter by its turning that much from it. In one case the sun's rays are caused to shine more perpendicularly, and in the other more obliquely. This wabbling, like that of a top, is the sole cause of the seasons ; since, owing to the eccentricity of our orbit, the earth is actually fifteen hundred thousand miles nearer the sun during our winter, in the northern hemisphere, than in summer.

"That there is no limit to a planet's inclination, and that inclination is not essential, we have astronomical proof. Venus's axis is inclined to the plane of her orbit seventy-five degrees, so that the arctic circle comes within fifteen degrees of the equator, and the tropics also extend to latitude seventy-five degrees, or within fifteen degrees of the poles, producing great extremes of heat and cold ...

"In Uranus we see the axis tilted still further, so that the arctic circle descends to the equator. The most varied climate must therefore prevail during its year, whose length exceeds eighty-one of ours. The axis of Mars is inclined about twenty-eight and two thirds degrees to the plane of its orbit ; consequently its seasons must be very similar to ours, the extremes of heat and cold being somewhat greater.

"In Jupiter we have an illustration of a planet whose axis is almost at right angles to the plane of its orbit, being inclined but about a degree and a half. The hypothetical inhabitants of this majestic planet must therefore have perpetual summer at the equator, eternal winter at the poles, and in the temperate regions everlasting spring. On account of the straightness of the axis, however, even the polar inhabitants if there are any are not oppressed by a six months' night, for all except those at the very pole have a sunrise and a sunset every ten hours ...

"The inclination of the axis of our own planet has also frequently considerably exceeded that of Mars, and again has been but little greater than Jupiter's ; at least, this is by all odds the most reasonable explanation of the numerous Glacial periods through which our globe has passed, and of the recurring mild spells, probably lasting thousands of years, in which elephants, mastodons, and other semi-tropical vertebrates roamed in Siberia, some of which died so recently that their flesh, preserved by the cold, has been devoured by the dogs of modern explorers.

"It is not to be supposed that the inclining of the axes of Jupiter, Venus, the Earth, and the other planets, is now fixed ; in some cases it is known to be changing. As long ago as 1890, Major-Gen. A. W. Drayson, of the British Army, showed, in a work entitled Untrodden Ground in Astronomy and Geology, ... that in 1900 (one hundred years ago) it would be 23° 27′ 08⋅8″. This natural straightening is, of course, going on, and we are merely about to anticipate it.

"When this improvement was mooted, all agreed that the extremes of heat and cold could well be spared. 'Balance those of summer against those of winter by partially straightening the axis; reduce the inclination from twenty-three degrees, thirty minutes, to about fifteen degrees, but let us stop there,' many said.

"Before we had gone far, however, we found it would be best to make the work complete. This will reclaim and make productive the vast areas of Siberia and the northern part of this continent, and will do much for the antarctic regions ; but there will still be change in temperature ; a wind blowing towards the equator will always be colder than one blowing from it, while the slight eccentricity of the orbit will supply enough change to awaken recollections of seasons in our eternal spring.

"The way to accomplish this is to increase the weight of the pole leaving the sun, by increasing the amount of material there for the sun to attract, and to lighten the pole approaching or turning towards it, by removing some heavy substance from it, and putting it preferably at the opposite pole. This shifting of ballast is most easily accomplished, as you will readily perceive, by confining and removing water, which is easily moved and has a considerable weight. How we purpose to apply these aqueous brakes to check the wabbling of the earth, by means of the attraction of the sun, you will now see.

"From Commander Fillmore of the Arctic Shade and the Committee on Bulkheads and Dams, I have just received the following by cable telephone : 'The Arctic Ocean is now in condition to be pumped out in summer and to have its average depth increased one hundred feet by the dams in winter. We have already fifty million square yards of windmill turbine surface in position and ready to move. The cables bringing us currents from the dynamos at Niagara Falls are connected with our motors, and those from the tidal dynamos at the Bay of Fundy will be in contact when this reaches you, at which moment the pumps will begin. In several of the landlocked gulfs and bays our system of confining is so complete, that the surface of the water can be raised two hundred feet above sea-level.

"'The polar bears will soon have to use artificial ice! Perhaps the cheers now ringing without may reach you over the telephone.'"

The audience became greatly interested, and when the end of the telephone was applied to a microphone the room fairly rang with exultant cheers, and those looking through a kintograph (visual telegraph) terminating in a camera obscura on the shores of Baffin Bay were able to see engineers and workmen waving and throwing up their caps and falling into one another's arms in ecstasies of delight. When the excitement subsided, the president continued :

"Chairman Wetmore, of the Committee on Excavations and Embankments in Wilkesland and the Antarctic Continent, reports: 'Two hundred and fifty thousand square miles are now hollowed out and enclosed sufficiently to hold water to an average depth of four hundred feet. Every summer, when the basin is allowed to drain, we can, if necessary, extend our reservoir, and shall have the best season of the year for doing work until the earth has permanent spring. Though we have comparatively little water or tidal power, the earth's crust is so thin at this latitude, on account of the flattening, that by sinking our tubular boilers and pipes to a depth of a few thousand feet we have secured so terrific a volume of superheated steam that, in connection with our wind turbines, we shall have no difficulty in raising half a cubic mile of water a minute to our enclosure, which is but little above sea-level, and into which, till the pressure increases, we can fan or blow the water ... We shall be able to find use for much of the potential energy of the water in the reservoir when we allow it to escape in June, in melting some of the accumulated polar ice-cap, thereby decreasing still further the weight of this pole, in lighting and warming ourselves until we get the sun's light and heat, in extending the excavations, and in charging the storage batteries of the ships at this end of the line. Everything will be ready when you signal Raise water.'" ...

... The building here fairly shook with applause, so that, had the arctic workers used the microphone, they might have heard in the enthusiastic uproar a good counterpart of their own period.

"I only regret," the president continued, "that when we began this work the most marvellous force yet discovered -- apergy -- was not sufficiently understood to be utilized, for it would have eased our labours to the point of almost eliminating them. But we have this consolation : it was in connection with our work that its applicability was discovered, so that had we and all others postponed our great undertaking on the pretext of waiting for a new force, apergy might have continued to lie dormant for centuries.

"With this force, obtained by simply blending negative and positive electricity with electricity of the third element or state, and charging a body sufficiently with this fluid, gravitation is nullified or partly reversed, and the earth repels the body with the same or greater power than that with which it still attracts or attracted it, so that it may be suspended or caused to move away into space. Sic itur ad astra, we may say. With this force and everlasting spring before us, what may we not achieve? ... 'Blessed are they that shall inherit the earth,'" he went on, turning a four-foot globe with its axis set vertically and at right angles to a yellow globe labelled "Sun" ; and again waxing eloquent, he added: "We are the instruments destined to bring about the accomplishment of that prophecy, for never in the history of the world has man reared so splendid a monument to his own genius as he will in straightening the axis of the planet.

"No one need henceforth be troubled by sudden change, and every man can have perpetually the climate he desires. Northern Europe will again luxuriate in a climate that favoured the elephants that roamed in northern Asia and Switzerland. To produce these animals and the food they need, it is not necessary to have great heat, but merely to prevent great cold, half the summer's sun being absorbed in melting the winter's accumulation of ice ... I suggest that we blow up the Aleutian Isles and enlarge Bering Strait, so as to allow what corresponds to the Atlantic Gulf Stream in the Pacific to enter the Arctic Archipelago, which I have calculated will raise the average temperature of that entire region about thirty degrees, thereby still further increasing the amount of available land ... Let us speed the departure of racking changes and extremes of climate, and prepare to welcome what we believe prevails in paradise namely, everlasting spring." ...

The Board of Directors having ratified the acts of its officers, and passed congratulatory resolutions, the meeting adjourned sine die.

PROF. CORTLANDT, preparing a history of the times at the beginning of the great terrestrial and astronomical change, wrote as follows :

"This period A.D. 2000 is by far the most wonderful the world has as yet seen. The advance in scientific knowledge and attainment within the memory of the present generation has been so stupendous that it completely overshadows all that has preceded ...

"Electricity in its varied forms does all work, having superseded animal and manual labour in everything, and man has only to direct. The greatest ingenuity next to finding new uses for this almost omnipotent fluid has been displayed in inducing the forces of Nature, and even the sun, to produce it. Before describing the features of this perfection of civilization, let us review the steps by which society and the political world reached their present state.

"At the close of the Franco-Prussian War, in 1871, Continental Europe entered upon the condition of an armed camp, which lasted for nearly half a century ... Further mechanical and scientific progress, however, such as flying machines provided with these high explosives, and asphyxiating bombs containing compressed gas that could be fired from guns or dropped from the air, intervened. The former would have laid every city in the dust, and the latter might have almost exterminated the race. These discoveries providentially prevented hostilities, so that the 'Great War,' so long expected, never came, and the rival nations had their pains for nothing, or, rather, for others than themselves.

"Let us now examine the political and ethnological results. Hundreds of thousands of the flower of Continental Europe were killed by overwork and short rations, and millions of desirable and often unfortunately for us undesirable people were driven to emigration, nearly all of whom came to English-speaking territory, greatly increasing our productiveness and power.

"Gradually the different States of Canada (or provinces, as they were then called) came to realize that their future would be far grander and more glorious in union with the United States than separated from it ... the States of Mexico, Central America, and parts of South America, tiring of the incessant revolutions and difficulties among themselves, which had pretty constantly looked upon us as a big brother on account of our maintenance of the Monroe doctrine, began to agitate for annexation, knowing they would retain control of their local affairs ...

"Manhattan Island has something over 2,500,000 inhabitants, and is surrounded by a belt of population, several miles wide, of 12,000,000 more, of which it is the focus, so that the entire city contains more than 14,500,000 souls. The several hundred square miles of land and water forming greater New York are perfectly united by numerous bridges, tunnels, and electric ferries, while the city's great natural advantages have been enhanced and beautified by every ingenious device. No main avenue in the newer sections is less than two hundred feet wide, containing shade and fruit trees, a bridle-path, broad side-walks, and open spaces for carriages and bicycles. Several fine diagonal streets and breathing-squares have also been provided in the older sections, and the existing parks have been supplemented by intermediate ones, all being connected by parkways to form continuous chains.

"The hollow masts of our ships (to glance at another phase en passant) carry windmills instead of sails, through which the wind performs the work of storing a great part of the energy required to run them at sea, while they are discharging or loading cargo in port; and it can, of course, work to better advantage while they are stationary than when they are running before it. These turbines are made entirely of light metal, and fold when not in use, so that only the frames are visible. Sometimes these also fold and are housed, or wholly disappear within the mast.

"Steam-boilers are also placed at the foci of huge concave mirrors, often a hundred feet in diameter, the required heat being supplied by the sun, without smoke, instead of by bulky and dirty coal. This discovery gave commercial value to Sahara and other tropical deserts, which are now desirable for mill-sites and for generating power, on account of the directness with which they receive the sun's rays and their freedom from clouds ...

"The medicinal properties of all articles of food are so well understood also, that most cures are brought about simply by dieting ... As a result of this, fresh air, regular exercise for both sexes, with better conditions, and the preservation of the lives of children that formerly died by thousands from preventable causes, the physique, especially of women, is wonderfully improved, and the average longevity is already over sixty ...

"Our political system remains with but little change ... English, as we have seen, is already the language of 600,000,000 people, and the number is constantly increasing through its adoption by the numerous races of India, ... and by the fact that the Spanish and Portuguese elements in Mexico and Central and South America show a constant tendency to die out, much as the population of Spain fell from 30,000,000 to 17,000,000 during the nineteenth century. As this goes on, in the Western hemisphere, the places left vacant are gradually filled by the more progressive Anglo-Saxons, so that it looks as if the study of ethnology in the future would be very simple.

"The people with cultivation and leisure, whose number is increasing relatively to the population at each generation, spend much more of their year in the country than formerly, where they have large and well-cultivated country seats, parts of which are also preserved for game. This growing custom on the part of society, in addition to being of great advantage to the out-of-town districts, has done much to save the forests and preserve some forms of game that would otherwise, like the buffalo, have become extinct ...

"Notwithstanding our strides in material progress, we are not entirely content. As the requirements of the animal become fully supplied, we feel a need for something else. Some say this is like a child that cries for the moon, but others believe it the awakening and craving of our souls. The historian narrates but the signs of the times, and strives to efface himself ; yet there is clearly a void, becoming yearly more apparent, which materialism cannot fill. Is it some new subtle force for which we sigh, or would we commune with spirits ? There is, so far as we can see, no limit to our journey, and I will add, in closing, that, with the exception of religion, we have most to hope from science."

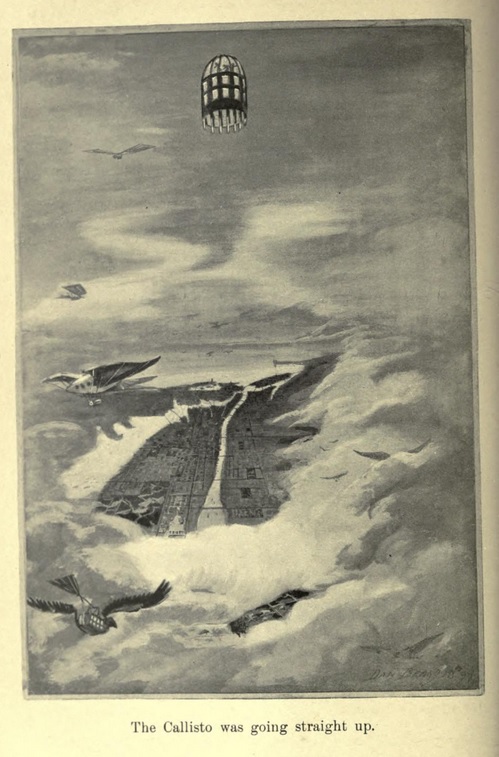

They had about as long a journey before them as they had already made in going from the earth to Jupiter. The great planet soon appeared as a huge crescent, since it was between them and the sun ; its moons became as fifth- and sixth-magnitude stars, and in the evening of the next day Jupiter's disk became invisible to the unaided eye. Since there were no way stations, in the shape of planets or asteroids, between Jupiter and Saturn, they kept the maximum repulsion on Jupiter as long as possible, and moved at tremendous speed. Saturn was somewhat in advance of Jupiter in its orbit, so that their course from the earth had been along two sides of a triangle with an obtuse angle between.

During the next four terrestrial days they sighted several small comets, but spent most of their time writing out their Jovian experiences. During the sixth day Saturn's rings, although not as much tilted as they would be later in the planet's season, presented a most superb sight, while they spun in the sun's rays. Soon after this the eight moons became visible, and, while slightly reducing the Callisto's speed, they crossed the orbits of Iapetus, Hyperion, and Titan, when they knew they were but seven hundred and fifty thousand miles from Saturn.

"I am anxious to ascertain," said Cortlandt, "whether the composition of yonder rings is similar to that of the comet through which we passed. I am sure they shine with more than reflected light."

"We have been in the habit," said Ayrault, "of associating heat with light, but it is obvious there is something far more subtle about cometary light and that of Saturn's rings, both of which seem to have their birth in the intense cold of interplanetary space."

Passing close to Mimas, Saturn's nearest moon, they supplemented its attraction, after swinging by, by their own strong pull, bringing their speed down to dead slow as they entered the outside ring. At distances often of half a mile they found meteoric masses, sometimes lumps the size of a house, often no larger than apples, while small particles like grains of sand moved between them. There were two motions. The ring revolved about Saturn, and the particles vibrated among themselves, evidently kept apart by a mutual repulsion, which seemed both to increase and decrease faster than gravitation ; for on approaching one another they were more strongly repelled than attracted, but when they separated the repulsion decreased faster than the attraction, so that after a time divergence ceased, and they remained at fixed distances ...

Landing on a place about ten degrees north of the equator, so that they might obtain a good view of the great rings since on the line only the thin edge would be visible they opened a port-hole with the same caution they had exercised on Jupiter. Again there was a rush of air, showing that the pressure without was greater than that within ; but on this occasion the barometer stopped at thirty-eight, from which they calculated that the pressure was nineteen pounds to the square inch on their bodies, instead of fifteen as at sea-level on earth. This difference was so slight that they scarcely felt it. They also discarded the apergetic outfits that had been so useful on Jupiter, as unnecessary here. The air was an icy blast, and though they quickly closed the opening, the interior of the Callisto was considerably chilled.

"We shall want our winter clothes," said Bearwarden ...

... Finding that the doctor's prediction as to the suitability of the air to their lungs was correct, they ventured out, closing the door as they went.

Expecting, as on Jupiter, to find principally vertebrates of the reptile and bird order, they carried guns and cartridges loaded with buckshot and No. 1, trusting for solid-ball projectiles to their revolvers, which they shoved into their belts. They also took test-tubes for experiments on the Saturnian bacilli. Hanging a bucket under the pipe leading from the roof, to catch any rain that might fall (for they remembered the scarcity of drinking-water on Jupiter) they set out in a southwesterly direction ...

"Is it possible we did not see them?" gasped Ayrault.

"We must inadvertently have walked some distance since we saw them," said Cortlandt.

"They were what I looked forward to for lunch," exclaimed Bearwarden.

They were greatly perplexed ...

"That humming confuses me so that I cannot work correctly," said he ...

"I found the same thing," said Bearwarden, "but said nothing, for fear I should not be believed. In addition to going blind, for a moment I almost forgot what I was trying to do."

Cortlandt worked the combination lock of the lower entrance, through which they crawled. Going to the second story, they opened a large window and let down a ladder ...

Bearwarden and Ayrault immediately set about combining the chemicals that were to produce the force necessary to repel them from Saturn. Bubbles of hydrogen were given off from the lead and zinc plates, and the viscous primary batteries quickly had the wires passing through a vacuum at a white heat.

"I see you are nearly ready to start," said the spirit, "so I must say farewell."

"Will you not come with us?" asked Ayrault.

" No," replied the spirit. "... The vision of your own grave," he continued, addressing Cortlandt, "may not come true for many years, but however long your lives may be, according to earthly reckoning, remember that when they are past they will seem to have been hardly more than a moment, for they are the personification of frailty and evanescence."

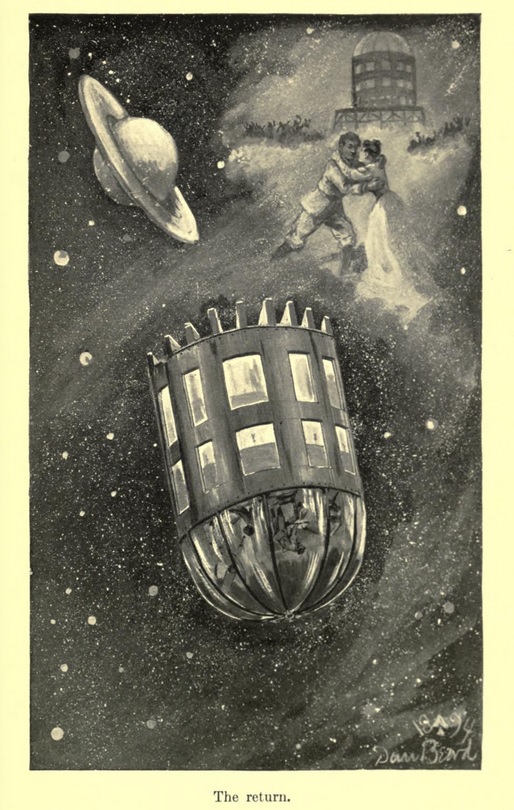

"I am overjoyed to see you," said Sylvia, when she and Ayrault met. "I had the most dreadful presentiment that something had gone wrong with you. One afternoon and evening I was so perplexed, and during the night had a series of nightmares that I shall never forget. I really believed you were near me, but your nature seemed to have changed, for, instead of its making me happy, I was frightfully distressed. The next day I was very ill, and unable to get up ; but during the morning I fell asleep and had another dream, which was intensely realistic and made me believe, yes, convinced me that you were well. After that dream I soon recovered ; but oh, the anguish of the first!"

Ayrault did not tell her then that he had been near her, and of his unspeakable suffering, of which hers had been but the echo ...

While Sylvia and Ayrault were standing up to receive the congratulations of their friends, Bearwarden, in shaking his hand, said :

"Remember, we have been to neither Uranus, nor Neptune, nor Cassandra, which may be as interesting as anything we have seen. Should you want to take another trip, count me as your humble servant." And Cortlandt, following behind him said the same thing.

Shortly after this, Sylvia went up-stairs to change her dress, and when she came down she and Ayrault set out on their journey together through life, amid a chorus of cheers and a shower of rice.

DR. CORTLANDT'S HISTORY CONTINUED.

"In marine transportation we have two methods, one for freight and another for passengers. The old-fashioned deeply immersed ship has not changed radically from the steam and sailing vessels of the last century, except that electricity has superseded all other motive powers. Steamers gradually passed through the five hundred-, six hundred-, and seven hundred-foot-long class, with other dimensions in proportion, till their length exceeded one thousand feet. These were very fast ships, crossing the Atlantic in four and a half days, and were almost as steady as houses, in even the roughest weather.

"Ships at this period of their development had also passed through the twin and triple screw stage to the quadruple, all four together developing one hundred and forty thousand indicated horse-power, and being driven by steam. This, of course, involved sacrificing the best part of the ship to her engines, and a very heavy idle investment while in port ...

"The next improvement in sea travelling was the 'marine spider.' As the name shows, this is built on the principle of an insect ... more like centipedes with large, bell-shaped feet, connected with a superstructural deck by ankle-jointed pipes, through which, when necessary, a pressure of air can be forced down upon the enclosed surface of water. Ordinarily, however, they go at great speed without this, the weight of the water displaced by the bell feet being as great as that resting upon them. Thus they swing along like a pacing horse, except that there are four rows of feet instead of two, each foot being taken out of the water as it is swung forward, the first and fourth and second and third rows being worked together ...

"Some passengers and express packages still cross the Atlantic on 'spiders,' but most of these light cargoes go in a far pleasanter and more rapid way. The deep-displacement vessels, for heavy freight, make little better speed than was made by the same class a hundred years ago. But they are also run entirely by electricity, largely supplied by wind, and by the tide turning their motors, which become dynamos while at anchor in any stream. They therefore need no bulky boilers, engines, sails, or coal-bunkers, and consequently can carry unprecedentedly large cargoes with comparatively small crews. The officers on the bridge and the men in the crow's nest (the way to which is by a ladder inside the mast, to protect the climber from the weather) are about all that is needed ; while disablement is made practically impossible, by having four screws, each with its own set of automatically lubricating motors ..."