|

Archives:

Fall 1999 Table

of Contents On a sunny July day on the tip of Nahant, a few bucket-toting beachgoers are gathering rocks and seashells. Above them, on a grassy hillock just downwind of Logan Airport, Dan Golomb is doing his own collecting with a pretty sophisticated system of buckets. For the past year, the UMass-Lowell associate professor in the Department of Environmental, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences and Ph.D. student George Fisher have been harvesting polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which are key ingredients in smog. PAHs are formed from the incomplete combustion of coal, oil, and gas. Black or blue smoke coming from a tailpipe or smokestack, says Golomb, is one telltale sign of PAH production. By measuring the amounts and identifying the sources of PAHs found on Nahant, the researchers hope to learn how these carcinogenic compounds arrive in Massachusetts Bay. That, in turn, should help coastal managers develop plans for decreasing the amount of harmful PAHs not just in Massachusetts Bay, but in many similar urban coastal areas. The research is funded by MIT Sea Grant.

PAHs are produced by a variety of sources: power plants, incinerators, boilers and furnaces, wood stoves, barbecues, lawn mowers, cars, trucks, and airplanes. Many PAHs are confirmed carcinogens for laboratory animals and are suspected carcinogens for humans. And, says, Golomb, "Bottom-living fish and crustaceans are affected by lesions and tumors that most likely are caused by the same PAHs." Just how do the PAHs get into coastal waters? Some come from spilled crude oil, leaching from paved roads, and dumped tar and residue oil. But, the primary source, says Golomb, is atmospheric deposition. That happens in two manners: dry and wet. In dry deposition,

airborne PAHs, in the form of vapor and particles, hit the ocean

surface and get absorbed. Explaining wet deposition, Golomb notes

that raindrops and snowflakes contain minute concentrations of PAHs.

"How do they get into raindrops and snow?" he asks. "As

rain or snow falls, it scavenges the PAHs that are airborne."

Those droplets then end up in coastal waters. "We created a

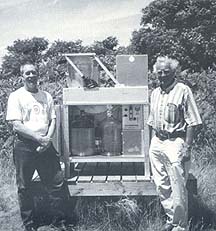

water surface which we expose to this direct impaction of mole- In an earlier project, Golomb made continuous measurements of PAHs in Nahant and in Truro, Mass. That work provided data on the total amount of PAHs that comes down per year per season. "But this project," says Golomb, "is really a whodunit," aimed at identifying the areas from which PAHs are streaming. Thus, the researchers are concentrating on episodes: collecting rain from one storm or PAHs that arrive when the wind is blowing from just one direction. This is accomplished via a wind vane next to the collection device and an innovative software program written by Fisher–whose earlier career as a meteorologist in the Air Force has come in handy. The program receives information from the wind vane and, depending on its sampling instructions, directs a motor to open or close a lid over the two collection spots. Fisher explains: "When it’s not raining, we have eight different sectors of compass we want to sample. If we want to collect from the north, the door will open and only collect when it’s not raining and the wind is coming from the north. The software allows us to change the sector that we are sampling. That will help us determine perhaps where the PAHs are coming from." With the collection device, wet precipitation trickles down a funnel into a cartridge filled with an adsorbent that removes PAHs. On the dry side (which collects PAHs on the pool of water), the water also runs down a funnel with a similar adsorbent. The adsorbed PAHs are then flushed out with a solvent so that they can be analyzed back at the lab with a gas chromatograph–mass spectrometer, which provides data on PAH content in grams per square meter per unit of time. That work is being carried out by Eugene Barry, a professor in the Department of Chemistry at UMass-Lowell. Golomb and Fisher are particularly interested in particles transported by northeast winds because Logan Airport lies directly southwest of the collection spot. According to Golomb, aircraft traveling to and from Logan are a major source of PAHs, which can be seen as a hazy dark thread in an otherwise blue sky. However, the researcher notes that the project doesn’t aim to point fingers at one airport or power plant, or even at a particular state or city. Instead, it focuses on source areas, figuring out where the clouds transporting PAHs originated. Using trajectory models published by NOAA, the investigators are able to backtrack clouds for 24 or 48 hours, thereby discerning "dirty clouds vs. clean clouds, or rain that contains a lot of PAHs and rain that contains little," explains Golomb. "Clouds that sweep up the Washington/Boston corridor seem to bring more PAHs than clouds that gather over the ocean and then precipitate here," he says. "This is fairly logical. Clean clouds came from systems that develop over the ocean and clouds from the southwest seem to bring more bad deposition." Eventually Golomb anticipates that the findings from this research will more closely pinpoint the culprits in PAH production. That, in turn, could help coastal managers with their jobs. "Suppose we found out that incinerators are a major source, then the managers would have to insist that the incinerators be run with more controls to catch more smoke," he explains. Gazing from Nahant to the airport, then to the Salem power plant in the northeast and the Saugus incinerator to the west, Golomb concedes that coastal pollution is inevitable with such urban sprawl. But by plucking a few PAHs from the air now, he hopes to ensure that less pollution winds up in Massachusetts Bay in the future.

|