|

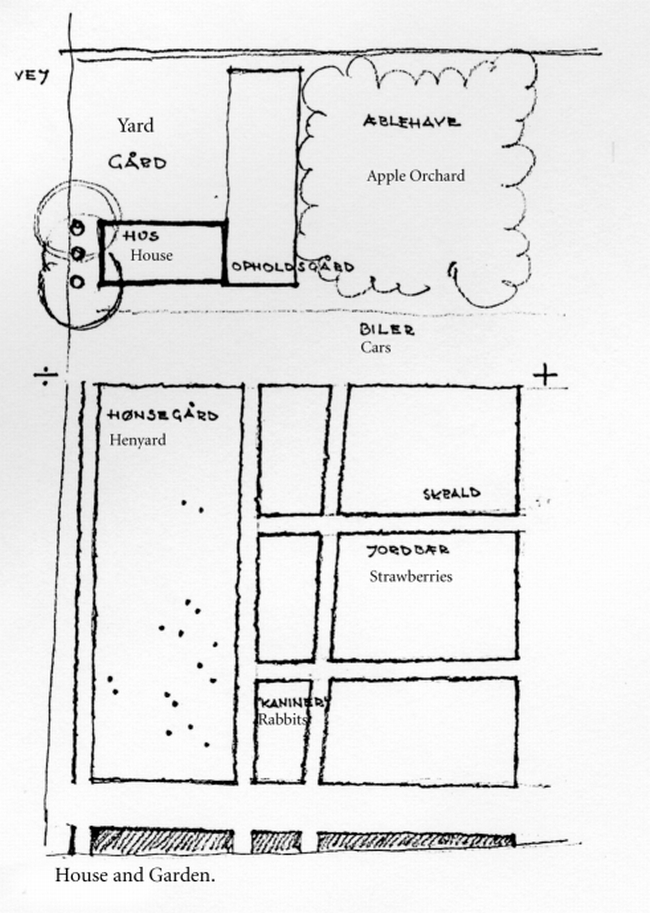

LETTER FROM MY HENYARD Sven-Ingvar Andersson Arkitekten (1967): 579-583 This essay was published first in 1967 as "Brev fra min hønsegård" in Arkitekten, the journal of the Danish Federation of Architects. The translation by Anne Whiston Spirn is copyrighted 2004. For permission to reprint, please contact spirn@mit.edu. There really is nothing to speak of but eggs so far. They won't begin to cluck for two or three years, and they probably will have to grow for another five to six years before they are finished – with feathers and all. But then it will be a really wonderful sight with all those beautiful birds coming tearing down the hillside with necks outstretched. The henyard isn't finished either, but so long as the chickens remain in their eggs, it really doesn't matter that the fence is only a meter high and open. In time it will reach four meter's height and be completely impenetrable to anything other than sparrows and robins who may make their nests there. This does not involve ordinary hens, you understand. They are made of plants – that is, they are about to be made of plants. Of hawthorn, clipped. First into tight balls, so that the birds, in their time, will not be bare-legged, then later, little by little, into hens two to three meters high. The fence will also be made of hawthorn. People have told me that animals belong in an adventure playground and that a man in my position is expected to have his affairs in order. I don't visit my playground frequently enough to keep living animals, so I have to make do with plant-animals. The henyard is part of a playground with a differentiated plan. Not with respect to traffic, but spatially. There are eleven rooms in all. The hens have the largest of the seven that are enclosed by hawthorn hedges. In others there are rabbits of boxwood, strawberries, compost, and fire. One is set aside for a hammock and one for people. And just as Winnie the Pooh has “an empty pot for useful things,” in our playground we have an empty garden room that can be used for one thing or another. •

Every man needs a nook, some corner where he can make something that doesn't have to add up to anything. A possibility for some kind of undertaking that doesn't have to be judged, at least not in connection with professional advancement, livelihood, or status. Women and children have the same need. This shouldn't necessarily be taken literally, this bit about the nook. Making music, for example, gives one the opportunity to stand back and recognize oneself, which many consider essential. For most people there seems to be a desire to mark their identity visually, that is, to make something or other that can be seen and that others can see. Children build their own worlds of thoughts, which we adults cannot see, but also of bricks, boxes, and beer cases if they can. Women have always made some kind of handicrafts over and above those chores which have been seen as their particular responsibility.

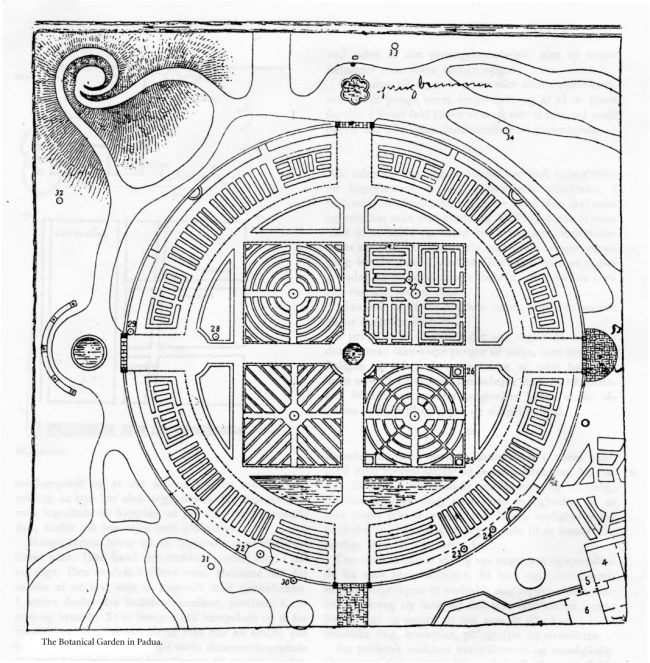

The result is that one way or another we decorate our surroundings, and we enjoy it. In any case, we grow grumpy when we aren't allowed to paint our door red or make psychedelic shop windows. • All kinds of societies in all times have established ways for limiting individual development. In our society, there are rules for what one should eat and how one should dress. When one builds a house on the Fiji Islands, one must abide by constraints set by material and technology, and once people lived in igloos in Greenland. Many rules are rooted in economic context, but there is no lack of social considerations either. One has to watch out that neither roof nor social status sticks up too far. In primitive societies, one doesn't just decorate one's environment, one makes it. One either makes house and furnishings, tools and clothes oneself or in close collaboration with a craftsman. People and environment become a strong and simple whole under such conditions. • The conditions are completely different in our society with its specialization and mass production. We have great freedom and economic opportunities to buy manufactured products, but the possibilities for making something ourselves are very few. Our potential for shaping is completely limited to combining finished things to form new wholes. The great quantity of things was something new and exciting for our grandparents. So the bourgeois home at the turn of the century became a veritable storehouse of things. At first one collected all those things factories could produce and later all those things they couldn't: exotic things, conch shells, peacock feathers, and beach pebbles. A puritanical reaction was necessary and unavoidable. The many things were replaced by the few, the wonderful by the modest, those rich in association by the unambiguously simple--the functional. Most important was that material, construction, and form were authentic and answered to a specific, legitimate need. Say, “fake,” and that which is framed is lost. The white living room with two sophisticated, simple chairs, placed side by side, a third of the way along the longest wall of the room, has not lost its grip upon the majority of architects. One finds it particularly advisable that the common man makes do with this pure clarity. Even though architects, with their well-developed taste and sense for the authentic may, of course, surround themselves with Japanese handcrafts, painted Mexican plaster figurines, and Balinese masks. It has an inspirational effect on the work of giving form! If one cannot trust the users to restrain themselves and/or to have good taste, architects ought to make sure that there are nice, neutral curtains which can be pulled shut. Now, we know that this is crazy, but the users were the first to understand that this is a good old double standard. Their opposition is, for the most part, passive. During the work week they hide their unaesthetic, thing-full, and inauthentic display behind the curtains, but all who have the opportunity parade it on the weekend an appropriate distance from their regular home. Summer house and weekend shack are adventure playgrounds for adults, places where we have the nerve to decorate with our multiple personalities, with all that we were brought up to be asshamed of in the real, productive, weekday world. Therefore they flourish – thatched roofs and planted wheelbarrows, miniature forests and wooden shacks, barbecue pits, and my hawthorn hens. • Freud and others have attacked the Victorian double standard, and slowly we bring ourselves to accept the fact that humans, in spite of everything, are animals. How then can we justify the aesthetic double standard which imprisons the user behind a nice facade and prevents him from the exuberant display and marking of place that could be the true folklore of industrial society? • I have a definite idea of how my henyard will end, but what lies between now and then is an open plan. If I am so fortunate to live to a patriarchal age and feeble senility, and if my henyard hasn't been torn down for a rocket launching pad or some other useful thing, sometime near the turn of the century, I will sit in a grove of hawthorns with a blanket around my legs. Perhaps there is a little clearing which lets the sun reach the ground in a few places, but mainly all that I have shaped has disintegrated now I no longer have the strength to hold clippers or clamber up ladders. My son-in-law has no interest for this sort of thing, and folk cannot be hired for garden work. Nonetheless, I am satisfied. The hawthorns are grateful for the freedom to develop a lovely, healthy growth. In early summer all the branches are covered with masses of yellow-white flowers, like whipped cream, which later fall to the ground like a silent snowfall, leaving the crooked stems standing black against the white ground. In fall, the branches are weighed down by dark red fruits and by all the birds that thrive in the sheltered world of the thorn grove and enjoy its edible fall dress. If I am truly fortunate, my great grandchild will dig holes under the trees. But a lot can happen before the henyard becomes a hawthorn grove. Except for the plants that will be shaped into hens, all the hawthorns are planted so that they form the sides of seven rectangles. This fixes the main framework, which can scarcely be altered. But there are many potential variations still open. How high should the hedges be? It's hard to clip them if they are over a meter and a half, but I would like to enclose the henyard a bit better, more for my own experience of the space than the need to keep the hens shut in. A position also has to be taken on whether the tops of the hedges should follow the slope of the terrain or lie in a horizontal plane. Or should the tops lie in two or possibly three different horizontal planes? This also depends upon the relationship to the surrounding landscape. A plane at the correctly-chosen level will yield a completely enclosed space in the lower part of the garden, and a view out over distant dales and ridges from the upper hedge-room. In the in-between spaces between the rectangles lie many other possibilities. One immediately experiences them as the garden's negative parts, as the separation between those parts which mean something, as passages from the house out to the attractions and activities. But it could also be just the opposite: all the in-between spaces could be made into enclosed leafy passages. They could be filled with fine, shade-loving plants or birdcages or moss-covered stones. From the rectangles one could peek in at these wonders through openings in the hedges.And how consistent should I be? Shall I perhaps use a bit of all the possibilities: positive and negative space structure, different room heights, open and closed spaces, spaces that gather themselves around something which happens on the ground plane or that open to the clouds; passages that follow the district's in-between spaces and passages that wind through the garden seemingly independent of the primary structure? Shall I perhaps make my playground into an illustration of “Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture” or shall I let form follow function in the hope that less is more? There are many Intentions in Architecture to choose from, and to the ecological requirements of the hawthorns, I can add my own social needs. The trees are planted, but my henyard is nowhere near finished. Despite the many possibilities, I am not anxious about the result. And even if it just becomes a big mess, it won't be all bad. My confidence stems not so much from a sense of my own ability to manage the affair, but from two facts: the simple pattern of the planting and the material, hawthorn. If I always proceed with a respect for the placement of the hawthorns and their existence as living organisms, they will always form a clear pattern that can adapt to whatever serendipitous circumstances are introduced by myself and by time. The hawthorns, on the other hand, permit enormous variation, from the meter high, closely-clipped to the freely-growing, five-meter tree. But not beyond those limits which lie in being a hawthorn, which means that every single cell, whether it sits in the roots or in the skin of the fruit, has a predetermined number of chromosomes with a particular set of genes, which can vary a little bit and give each plant its unique individuality, yet still ensure similarities in form and in mode of adapting to external conditions. • In the discussion of the flexible and the fixed, dynamic and static, open, functional plan and closed, formal plan, some would say that the conditions change so quickly that it is useless to plan. It is more important to produce, they say, and to produce so much so cheaply that we can discard and make anew as needs and opportunities change. In the slightly more bounded discussion about our need for an unfinished environment, it would mean that one gives in to the free play of forces and accepts chaos as the aesthetic of our time. Then one forgets, I believe, that humans, just like hawthorns, are very adaptable, but still bound to their genetic structure which is unchangeable. (Mutations are infrequent and most people would consider manipulating the laws of heredity inhumane.) And I don't think I am wrong if I believe that in our genetically fixed pattern there is also a need for stability in our physical surroundings, as well as the need for freedom, diversity, and individual development. The task, then, is to find the balance. Often we planners are so busy specifying all the details, and, if our clients have exchanged beargrass for red roses or bought solid lounge chairs instead of the Kj?rholm-poem we recommended, we think our work has been ruined, and we have to move everything around before we can photograph it. In those places we study as precedents there are also many fine details: the door handles of the Kunstindustri Museum in Copenhagen, the paper screens in Katsura, the fortifications in the Generalife, etc. But there are also environments that are exciting because they permit a brilliant freedom against the background of a fixed feature in the landscape context or in the pattern of the plan. I am thinking of such cities as Portofino, which presses up against the city walls in delightful irregularity. Of Dutch cities subordinated to the necessity of the canal pattern. Of Lucca, where the construction around the old ampitheater is both rigorously restrained and unbounded, free. Of Paris, where Louis XIV and Napoleon III managed, with Le Nostre's and Hausmann's help, to give a structure, which, despite great opposition in implementation and much critique by posterity, unified the richness of variety and change with well-planned clarity. (Unity and variety, as Le Nostre said.) I also think about the fact that the only ideal city planned in detail that still functions well is the botanical garden at Padua. But, then, it is plants that are concerned there. • What about a synthesis and a conclusion? I am not up to it.

I can only see the problem from within the closed world of my henyard.

Others, who keep pigeons, may be more fortunate.

|