A view down Commonwealth Avenue

A view down Commonwealth Avenue The Back Bay seems to me what a “typical” city of the Northeast is like. Granted, my concepts may be a bit skewed, since I have lived most of my life in South Florida. But when I think of New England, the idea of quaint brownstones and one way streets immediately fills my mind. Brick buildings and fire escapes winding down narrow alleyways. The streets are quiet but busy; any sound is muffled by the perpetual cloud of gloom that I’ve learned to recognize as the trademark of Boston weather. And Back Bay is just this. I find it a peaceful place to be; the more I visit, the more I want to go back. There’s just something about those brownstones that feels so calm and inviting. And yet, I constantly see waves of people scurry about. Their flurry of action is almost comical paired with the stoic facades of brownstones that have been there for almost two centuries. They’re just walking down the street, completely mindless of the rich life around them—the life embedded in the buildings and in the streets. No one sees the history etched into the pavement.

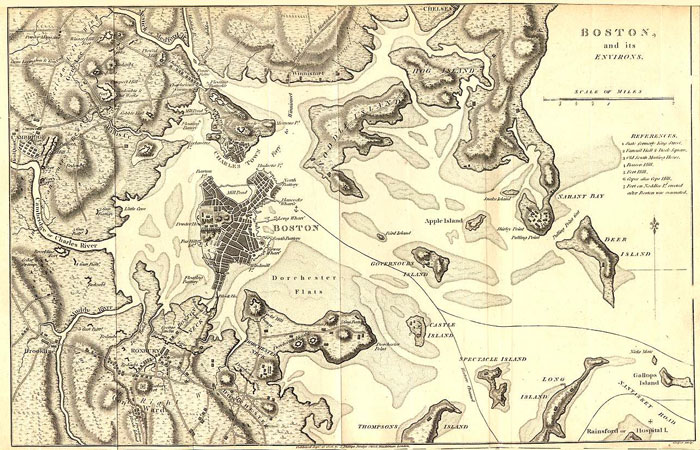

Back Bay is thus called because originally, it was just marshes and water. There were hills, at one point, that were leveled and used to fill the surrounding marshland. In the 1880s, this project was completed, drastically increasing Boston’s boundaries and giving birth to a new bay. It was behind the “front” that is Boston Harbor and thus, it is Back Bay.

A map depicting Boston in the 1800s before the fill was completed. At this point, the Back Bay is still under water.

A map depicting Boston in the 1800s before the fill was completed. At this point, the Back Bay is still under water.

Evidence of this historical fact is clearly visible on the urban landscape. For one, the land drops off dramatically as Boston slopes into the Charles River. The banks are not wide and subtly inclined, like a natural river bank is. Instead, the bank slopes off rapidly from the street to the river, the inclination obvious. This is due to the rapid accumulation of matter into a compacted form. The builders didn’t try to make the slope gradual, because there was no need for it. Once they’d reached the size of land they wanted, they just created a decline and were done. The pockmarks in the roads are another tell-tale sign. Since the land is filled, there are bound to be air pockets and places where the land isn’t completely compact. Once things start being built, the weight of all of it will keep pushing the land down until something shifts and the ground gives way. This causes “fatigue cracking”, where the under-layers of the road are too weak and give way (Elkins). This is what causes cracks in the roads that eventually lead to potholes.

Trees down the east side of Beacon Street

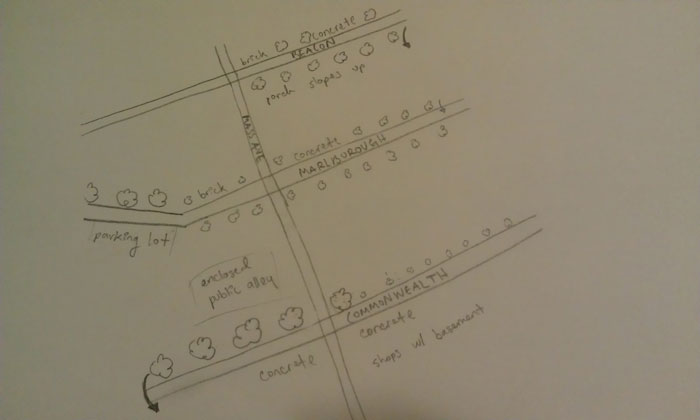

Trees down the east side of Beacon StreetTake Beacon Street, for instance. There are trees planted by the city on the curbside, as well as trees planted in the front yards of the homes situated here. The trees planted next to the street are of varying sizes, but are spaced in equal increments—thus, it shows that these trees are cared for by the city and are planted there to adorn the street. Some of these trees are rather small and thin. Either they are newly planted trees; or their growth has been so stunted that they look like young trees, but are in fact several years old. And yet, there are some very large trees present here in the same environment as the little trees. How is this possible? These large trees defy all odds to even survive. In The Granite Garden, it states that the toxidity of street-side soil is a massive problem. I've never really thought about this, but now I wonder how the street trees even survive with such toxic soil. "The soil adjacent to a busy street may contain thirty times the lead of a nonroadside soil" (Spirn). And yet these trees have managed to beat all the odds and thrive. My theory is that the roots of the larger trees have been able to wiggle out of the concrete box and into the plots of soil that exist on the front gardens of the adjacent buildings. Although this plot of land is not at all large, it may still be big enough to provide a tree with the necessary nutrients. The observation that led to this theory is the fact that the slabs of concrete between many trees and the front gardens are buckled and raised, forced apart by the strength of the roots.

![]() Evidence of the concrete slabs being pushed up by the tree's roots on Beacon Street

Evidence of the concrete slabs being pushed up by the tree's roots on Beacon Street

Marlborough Street

Marlborough StreetMoreover, this part of the street looks like it may not have been well cared for. It even exhibits poor planning (or lack thereof). The first four trees present on the north side of the street are very thin and small, planted curb-side. Normally, this would mean that the city put them in and thus they’d be equally spaced. But these trees seem to be randomly dispersed down the sidewalk. After this set of four, the next tree visible is in a private garden, not a curb-side plot. And it is massive, startlingly so next to the spindly trees that come before it. It has a bit of vine growth, and there seems to be a mangled trunk spiraling up its sides. The ones that come after this tree are rather large as well, all of the growing almost haphazardly. It is these trees that inflict the most visible change in the road—pushing up the pavement in waves, and breaking through the concrete curbs put in to hold them in place. The large trees are tiny walkways give this side of Marlborough Street a secluded and (literally) shady look.

A view down the west side of Commonwealth Avenue

A view down the west side of Commonwealth AvenueAnd yet, the huge trees present here are nothing compared to the trees on the west side of Commonwealth Avenue. These monstrous trees tower over the street side, leaning heavily into the street. These giants bring back the earlier question of how they are even standing. They have a much greater disadvantage than the trees on Beacon Street, since Commonwealth is a broad avenue for two-way traffic, with the end of the Green Belt running through the center. Not only that, but the sidewalks are three slabs of concrete wide, as opposed to Beacon’s two.

In stark contrast, the east side of Commonwealth has only one of these giants present, planted in private plots. The rest of the trees on this block are small and spindly. Instead of the enormous street-side trees, this side of Commonwealth has decorative lamps. And the north-facing side of the street has virtually no trees, since this side of the street receives markedly less sunlight than the opposite side of the street would. The south-facing wall gets much more direct sunlight than the north-facing wall does, giving plant life more favorable conditions.

As always, anomalies do occur. As previously stated the “optimal” location for plants is along the south-facing wall. It is here that trees would grow biggest and healthiest. And yet, many of the south-facing trees lean heavily into the street while the trees on the opposite side stand relatively straight. This type of behavior can be seen on both Commonwealth Avenue and Beacon Street. Because the trees on Commonwealth are much larger, their tilt is much more obvious. On Beacon, it is easy to see that the trees on the south-facing wall lean heavily out into the street, while the ones on the north-facing side stand straight up. This could be due to the fact that, since sunlight is heavier on the south side of the tree, the tree will naturally want to grow in that direction so as to receive maximum light. And perhaps the trees on the north-facing wall are so submerged in shadow, that the tree feels no difference in growing straight up, or tilting to the side.

Anomalies in tree growth can also be caused by the type of ground a tree is set in. As previously mentioned, a tree surrounded by concrete will obviously have more difficulty growing than a tree set in a large patch of soil would. This is evident all across the Back Bay.

Marlborough is a prime example of this. Looking at the south-facing side of the street, one would expect that the trees would be pretty much the same, considering that they receive the same amount of sunlight. But obviously, this is not the case, for the east side of Marlborough has smaller, thinner trees than the heavyset trees found on the west side. This is due to the fact that the east side of Marlborough has concrete sidewalks, while the west side has sidewalks make of brick set in dirt. Thus, the trees on the east side can only shoot roots in the small plot of land that it is given. The trees on the west side, on the other hand, are free to extend their roots further underneath the sidewalk. Another major advantage of brick is that air and water are allowed to cycle through the material. Concrete suffocates the roots of the tree and doesn’t allow any nutrients to flow through to the roots, causing the tree to be unhealthy. And this is apparent in the two streets. The trees on the east side are thinner and smaller because they aren’t as healthy. Also, it could be that they are this small because they are new, since the city would have to keep planting new trees every time the lack of nutrients killed a street tree.

Because this tree is set in a it's own plot, with brick sidewalks, it has much more freedom to expand.

Because this tree is set in a it's own plot, with brick sidewalks, it has much more freedom to expand.

Entrance to the hidden alleyway

Entrance to the hidden alleywayWith all of these quirky details, I have grown to love Back Bay. To get there, I always walk across the Harvard Bridge, relishing in the refreshing pause from the hectic campus life. The sight of the sturdy brownstones is so comforting for its quiet, neighborhood feel. I suppose I like it because it reminds me of the reliability of the suburbs, without the suffocating monotony. As you keep walking down Massachusetts Avenue, you encounter mostly residential buildings. Any commercial activity is either on Mass Ave or just around the corner. But it is still a largely residential area. The streets aren’t too wide, since they’re just one way. And, as has been thoroughly mentioned, there’s an abundance of trees.

But then, a few blocks down, you cross Commonwealth Avenue and are suddenly struck with a metropolitan chaos. A highway runs down Newburry Street, making that crossing a perpetual nightmare (now more so with the construction going on). A cluster of mismatched buildings and awkward intersections greet you with the roar of incoming traffic. Suddenly you realize that Boston is full of college students and they all decided to show up at the same time. The stark contrast between this zone and Back Bay is incredible, making Back Bay seem like time capsule, preserving the calm of an era past.

My own map showing a rough size distribution of trees and details.

My own map showing a rough size distribution of trees and details.

Bibliography

Clay, Grady. Close-up. How to Read the American City. New York: Praeger, 1974.

Vitale, Don. "Boston and Its Environs." Map of , Circa 1800. Archiving Early America, n.d. Web. 05 Mar. 2013.

Spirn, A. (1984). The granite garden: urban nature and human design. New York: Basic Books