Introduction

In a historical city like Boston, almost every district has its own unique story of its changing character and the socioeconomic factors driving those changes. Even though the Boston Financial District was part of the original Boston and had been a gather place for merchants and commerce since the 1700s, it was nearly destroyed in the Great Boston Fire of 1872. In consequence, with the exception of street layouts, the present day Financial District only tells a limited part of its tale, specifically, the part that occurred after the Great Fire.

At the time, powered by the Industrial Revolution, the textile industry occupied most of the area, taking full advantage of the harbors at Long Wharf with its rich flood of raw materials and its access to consumers around the globe. However, as competition increased globally within the industry, the Boston textile industry saw its decline. At the same time, the prosperous financial industry and the increasing need for office spaces in downtown Boston took over the area. Architects and designers were hired to repurpose the textile warehouses and stores for commercial needs. Each taking a different approach, some architects chose to reuse the original buildings as much as possible, some attempted to integrate the parts of the original buildings in their new design, while others torn down the old completely in favor of a drastically different design. Their different approaches resulted in a diverse building environment, showcasing a juxtaposition of building with similar purposes but in drastically different architectural styles (Hayden).

Boston’s Financial District is a prime example of American cities’ transformation from industrial centers to commercial centers, revealing key shifts in the urban landscape.

Traces of History

Figure 1. Summer Street (Source: Google Maps).

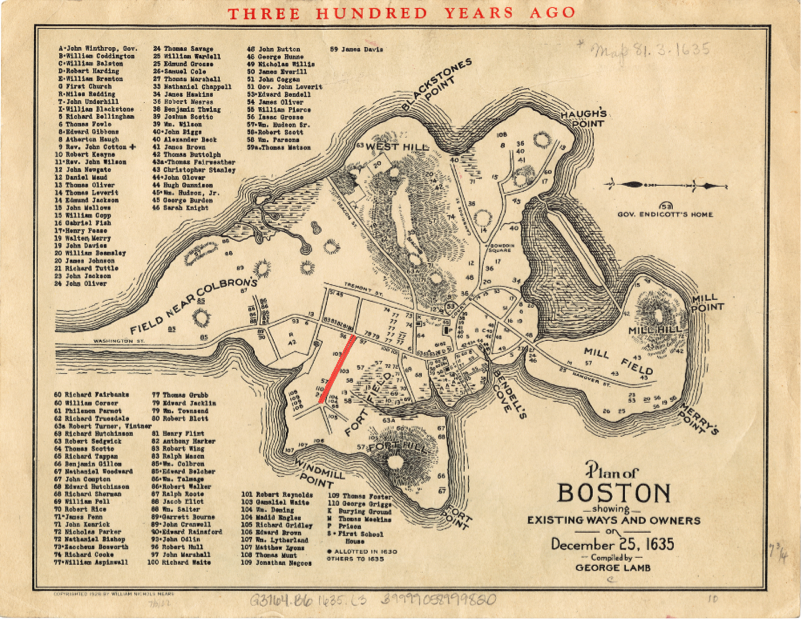

Figure 2. Map of Boston in 1635. Red line marks Summer Street. (Source: Massachusetts Historical Society)

The most original historical artifacts still present in the Financial District right now are none other than the streets dividing the area. Comparing historical maps, one can see that the streets were incrementally put in over the course of the past 300 years. Nonetheless, they are almost completely unchanged from their original layouts. Summer Street was one of the first streets in Boston to be laid out (see Figure 2, Summer Street is highlighted in red); and it remained one of the most major and busiest streets in the Financial District nowadays, with many cross streets both originating from and intersecting it (Figure 1). Historically, Summer Street, with its abundance of businesses, had been the center of the industrial activities in Boston, especially in the context of the textile industry. Though the industry is virtually nonexistent in the Financial District now, Summer Street is still the center of commercial activities. One can observe from Figure 1 that the street is filled with office supplies stores and other shops servicing the white collar community working in the financial industry. Summer Street’s present thriving business community reflects its historical significance as the first street in the district to be constructed (See Figure 2) and its role as the center of the commerce in this area (Spirn).

![Description: HD:Users:angelaz:Dropbox:Photos:[United States]:130417 Financial District:IMG_4112.JPG](3.png)

Figure 3. Multiple layers of buildings (Personal Photograph).

The Great Fire of 1872 effectively eradicated all the manmade structures that were built prior to the fire. Therefore, it is impossible to find buildings and other manmade structures from before the late 1800s in this area. The oldest existing structures in the district today dated from the 1880s and 1890s. Though the current building community consists primarily of office buildings, it is very diverse in terms of architectural styles and building ages. As shown in Figure 3, a small city block contains buildings ranging from the modern high-rise that is the Fiduciary Trust Company, an older six-story building with stores on the ground level, a taller residential building that looks like it was squeezed in between its neighbors, and another office building to its right (Figure 3). The multi-layered nature of the Financial District region is a result of the different approaches to repurposing warehouses for office use. While some architects elected to preserve as much original building spirit as possible, others chose to tear down the old structures completely and build modern skyscrapers in their place. Though the fire prevented us from finding evidence of the oldest history of the Financial District from its present state, we can nonetheless learn much about the district’s happenings thereafter by simply walking around the neighborhood and analyzing the various historical artifacts.

Decline of the Textile Industry

![Description: HD:Users:angelaz:Dropbox:Photos:[United States]:130417 Financial District:IMG_4137.JPG](4.png)

Figure 4. Historical plate near One Lincoln Street (Personal Photograph).

Boston is no longer known for manufacturing textile today, yet evidence of the industry’s past glory is still clearly visible to the careful eye. Next to One Lincoln Street, visitors can easily spot the wall on the side of the building with a short description of the history of Boston’s textile industry (Figure 4). The wall has been built using the remnants of the building, 80-86 Kingston Street, which had stood there until the 2000s.

“80-86 Kingston Street was noted as a fine example of the late 19th century fireproof construction. It housed a succession of small-scale clothing-related manufacturing firms through most of the 20th century… The textile industry was previously located in the adjacent commercial palace district which arose from the ruins of the Great Fire of 1872. That conflagration devastated the central city… By the early 20th century, Boston was noted as the largest woolen market in the United States…

January, 2004”

– Text on the wall

Though the wall was built in the early 2000s, it represents city planner’s attempt to celebrate Boston’s once prosperous textile industry and its status as the “birthplace of the ready-made clothing industry” (text on the wall). The Boston Financial District was then packed with wool warehouses, clothes sewing plants, and related businesses. The existence of the wall and the text on it reminds Bostonians of the rich history behind the Financial District and shows a glimpse of the textile industry’s past glory and dominance.

![Description: HD:Users:angelaz:Dropbox:Photos:[United States]:130417 Financial District:IMG_4142.JPG](5.png)

Figure 5. Textile shop (Personal Photograph).

![Description: HD:Users:angelaz:Dropbox:Photos:[United States]:130417 Financial District:IMG_4146.JPG](6.png)

Figure 6. Silk Screen print shop and the Farley Harvey Company Building (Personal Photograph).

As I walked around the neighborhood, to my surprise, I was able to locate some of the last surviving evidence of the once prominent textile industry (Figure 4 & 5). It is no surprised that both the textile store Clement’s Textile (in Figure 4) and the silk screen-printing shop (in Figure 5) reside in rundown brick buildings that have not been remodeled to become office buildings. Even though it was mid-day during a weekday when I visited the site, both of these stores were completely empty and looked like they were bordering being out of business. The building that houses the silk screen-printing shop has painted gold letters “Farley Harvey Co” on its exterior, indicating its ownership. A quick Google search would indicate that Farley Harvey Co was in the linen textile business, further reaffirming the historical prevalence of the textile industry in this area. Just across the street from this building, a new office building is under construction (Figure 6). The contrast between the soon-to-be new high-rise and the old run down textile building is stunning. One cannot help but wonder how long it will be until the Farley Harvey building gets torn down in favor of more office spaces, erasing what little remains of the textile industry.

Rise of Commercial Office Buildings

As the textile industry continuously declined, the need for commercial office spaces in downtown Boston increased steadily. In order to fulfill this need, the property owners sought means to repurpose their properties to serve as office buildings. There are several different approaches to this reconstruction.

Figure 7. One Winthrop Square (Personal Photograph).

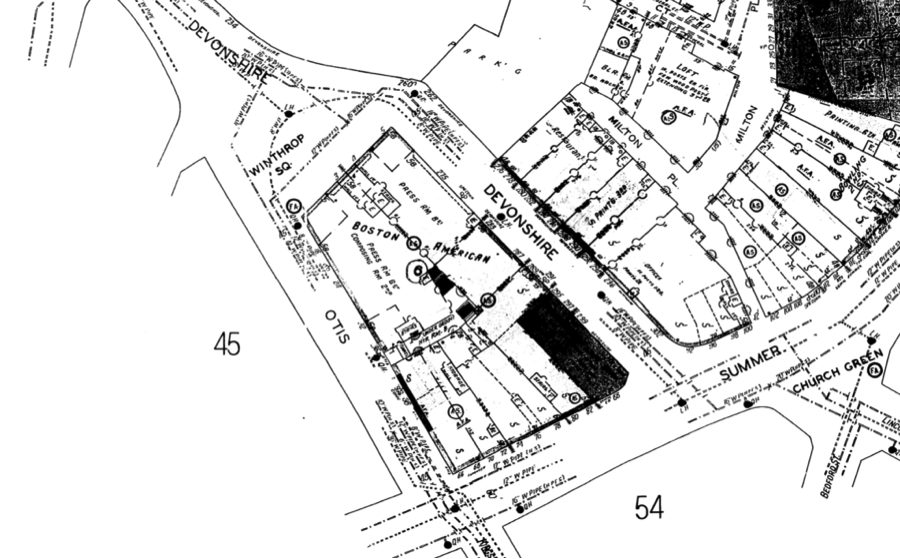

Figure 8. One Winthrop Square in 1929 (Source: Digital Sanborn Maps from UMI).

In some cases, the existing characters and context of the original buildings were carefully respected when the architects were repurposed for office buildings. The reconstructions were minor and discrete, preserving the original spirit of the place almost entirely. Built in the late 1800s, One Winthrop Square (Figure 7) was originally the New England Press Building (Figure 8), where newspaper content was written and edited by writers in one side of the building and printed in another. Though its surrounding buildings have been torn down and rebuilt as high-rises since then, One Winthrop Square’s exterior remained almost identical to its original building plan. Looking closely at the building, I could see that the interior of the building has been redone to be better suited as an office building and the windows on the building looked like they’ve been replaced and put in recently. However, these new elements are intentionally chosen in harmony with the style of the old structure. At a glance from afar, one would almost believe this building has been untouched since its inception, though this is clearly not an accurate assessment upon careful examination.

It is rather uncommon to see an historical building go through repurposing while still being able to preserve its original spirit like One Winthrop Square. I speculate there are several reasons for its preservation. First of all, the design and construction of the original structure was well planned out and executed. The building has no major flaws that would have been revealed during its first usage cycle. Secondly, the building must have been well maintained after its inception, with no destruction by major natural disaster. Finally, either the building must be originally designed to be adaptable enough to suit different purposes, or the new purpose of the building must be similar enough to the previous one that little redesign is required. In the case of One Winthrop Square, there was nothing about this building that was strongly tied to its historical role as a newspaper building. It has a building type is fairly generic and hence is versatile enough to be transformed into shops and offices with little disruption. As a result, it stands today distinct from the surrounding modern skyscrapers and tells its history as a newspaper printing press once serving the New England region (Hayden).

![Description: HD:Users:angelaz:Dropbox:Photos:[United States]:130417 Financial District:IMG_4129.JPG](9.png)

Figure 9. Current day, 125 Summer Street (Personal Photograph).

![Description: HD:Users:angelaz:Dropbox:Photos:[United States]:130417 Financial District:IMG_4117.JPG](10.png)

Figure 10. Current day, 125 Summer Street (Personal Photograph).

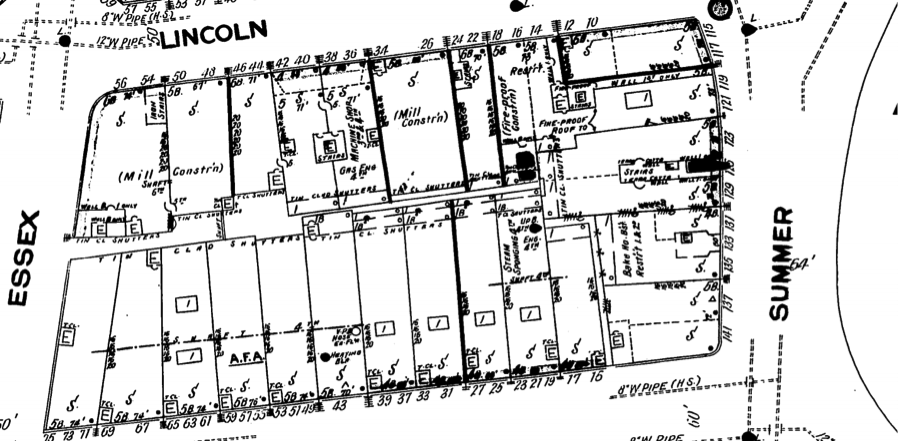

Figure 11. Map of 125 Summer Street in 1909. Source: Digital Sanborn Maps from UMI.

It is more often the case that as a building lot acquires a new occupancy and a new usage, the original building fails to accommodate the new requirements, and demands more major and fundamental changes. Architects charged with the task of turning residential complexes and old warehouses to office buildings and skyscrapers sometimes sought creative means to preserve the original architecture. In the case of 125 Summer Street, the old, five-story brownstones that had taken up the lot were deemed inefficient in terms of utilizing its vertical space. By the time it was redesigned for offices, the invention of safety elevators had enabled buildings to expand upwards, increasing its usable surface space by a factor of ten, using conservative estimates. Consequently, architects decided to build a high-rise on top of these old houses and stores. By integrating the old and the new, these architects managed to create one of the most unique buildings in the Financial District.

Today, a modern office building stands at 125 Summer Street (Figure 9 & Figure 10). Looking at old maps of Boston from the early to mid 20th century (Figure 11), one can see that, until the late 20th century, many stone and granite houses collectively occupy this lot. As seen in Figure 9 and 10, the partial façade of the original structures was incorporated into the design of the new high-rise in its space and presides at the corner of Summer Street and High Street, embedded in the base of the new twenty-two story office building. The juxtaposition of the old and the new gives this building a style unique to cities like Boston, where the preservation of the past and the commercial needs of the present mix frequently to make for unexpected sceneries.

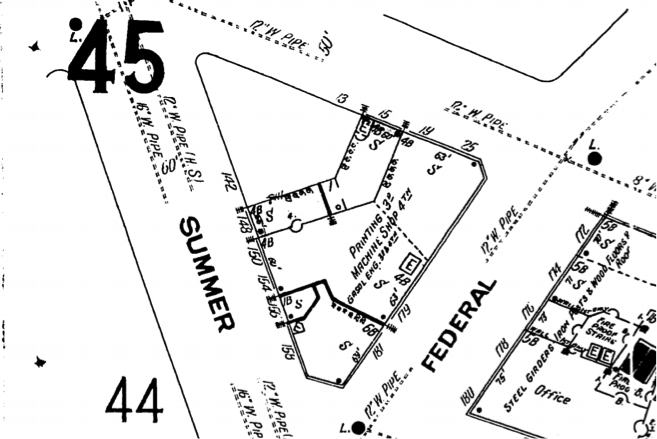

Figure 12. Map of 175 Federal St in 1909. Source: Digital Sanborn Maps at UMI.

Figure 13. 175 Federal Street, now Fiduciary Trust Building. Source: http://wikimapia.org/.

The most common case of building reconstruction in the Boston Financial District is undeniably the scenario where old buildings are completely torn down in favor of the new skyscrapers. For example, 175 Federal Street used to be a large printing and machine shop (Figure 12). However, when one visits the site today, traces of the original printing and machine shops are nonexistent. Instead, a concrete mushroom-like tower, the Fiduciary Trust Building, was built in its place around the mid to late 1900s, judging from the design and structure of the building (Hayden, 226-238). It is apparent to a visitor when s/he reads the occupant directory that this building occupants include large financial firms like the Fiduciary Trust Company and Bank of America; printing and machine shops, on the other hand, are nowhere to be found in the directory. This kind of complete renewal of a city block is very common in the Financial District, as well as in other urban centers across the globe. As a result, most existing buildings in the Financial Center today completely replaced and erased any traces of their predecessors.

Summary

This diversity in age and style distinguished the Boston Financial District from comparable downtown districts in newer cities, both in the United States and in metropolitan areas within developing nations. It is also a scene common to the original pre-landfill parts of Boston, where urban development was more of a gradual and natural process, in comparison to the newer and carefully planed out parts of Boston built on filled land in the span of less than a decade. The Financial District saw the rise and fall of the Boston textile industry, followed by the rising financial industry and more generally the skyrocketing demand for office spaces in downtown areas. Throughout the years, it has transformed itself to better adapt to the ever-changing demands for urban infrastructure created by the advancements in technologies and trends in the economy. The Financial District, as it stands today, tells a compelling story about its past and the path that has led it to its present state. What particular economic demand will drive its future is difficult to predict, but if there is one thing I can certain of, it is that no matter what lies ahead, the Financial District will eagerly transform itself to suit its occupants, one building at a time.

Bibliography:

Dolores Hayden, The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History (MIT Press), 14-43, 226-238 (on Stellar).

Spirn, “The Yellowwood and the Forgotten Creek,” in The Language of Landscape (Yale University Press), on Stellar).

The West Philadelphia Landscape Project Web site: www.wplp.net.