Assignment 2: Natural Processes

Charles Bulfinch’s map of the proposed Bulfinch Triangle. Mill Pond is outlined in blue, while my site for this project is shaded in blue. Map reproduction courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.[1]

While it may initially appear to be a paved, urbanized area devoid of nature and isolated from change, there are many clues around Bulfinch Triangle that hint at how it has been and continues to be influenced by environmental processes over time. The site is the result of an interaction between the natural setting of the site and the human needs like food processing power, sanitation, and living space. Despite being a piece of city that has had quite a lot of human intervention from the very beginning, it has been shaped by ongoing natural processes that the early Bostonians who built it probably did not foresee. Many irregularities in the patterns of the Triangle can be traced back to a combination of its environmental history, specifically, its past as a filled in pond, with the settling of the soil since then having caused changes in the surface of the brick, concrete, and asphalt of the ground. The movement of water through the site is also both an indicator of how the site continues to change, and a motive force for the decay of the structures built there. Bulfinch Triangle exemplifies how whatever man builds straight and true, nature will eventually render more organic.

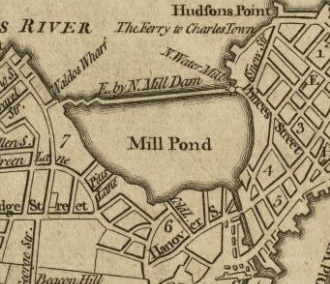

1774 Map of Boston, showing the Mill Pond that would eventually become Bulfinch Triangle. Map reproduction courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library. [2]

As shown on the earliest maps of Boston, there was no Bulfinch Triangle in early Boston. According to Prof. Jeffery Howe, the area was previously on water, with the North Cove being dammed to create Mill Pond, so named because tidal waves powered a mill at the outlet of the dam. This pond was later filled in with soil from the nearby Beacon Hill, and Bulfinch Triangle was named after the architect who engineered the project. [3] The fact that this site is built on filled in land has massive consequences for the formation of the urban architecture there, and is the major cause for what gives it its characteristics today. In The Granite Garden, Anne Spirn asserts that “In coastal cities like Boston, half the downtown may have been constructed on filled land, whose stability depends upon its content and length of time it has been in place.” [4] While Mill Pond was filled in with relatively stable and homogenous materials, this concept is fundamental to how natural processes have changed and shaped Bulfinch Triangle over the course of 200 years and will continue to do so.

The bricks of this sidewalk show a sharp break between the bricks within the building’s footprint and the bricks outside of it, a sign of the shifting soil underneath the sidewalk.

Throughout the site, the sidewalks are sloped downwards towards the middle of the street, with the curb lower than the edges of buildings. While at least some of this was certainly planned to aid in drainage, the cracks between buildings and the sidewalk hint at what is happening to the underlying soil. Building foundations may have been filled in with more solid materials, while the sidewalk was simply bricked or paved over, causing it to settle and shrink at a different rate from the building foundations. This manifests itself in as the sidewalk peeling itself from the edges of buildings, and sharp breaks in the slope of the ground when the sidewalk extends into the footprint of a building. Additionally, the facades of many of the buildings are cracked in the front, usually but not always perpendicular to Causeway Street. Given that much of Boston was built on water in a similar manner to Bulfinch Triangle, it would be reasonable to expect this to be a pattern that is consistent throughout much of the landfill parts of Boston, and an issue that will continue to be relevant for any future constructions.

Much of Canal Street features brick-lined sidewalk, which readily shows evidence of the movement of the underlying soil as it bends and buckles, but cannot stretch to keep aligned with the shoulder of the road.

Though Canal Street may now be several blocks from water, Bulfinch Triangle was once bisected by a canal next to the titular street. Ostensibly, this was filled in at a later date since the canal no longer exists. Filling in the canal at a later date would create a region with newer, less settled soil that moves differently from its surroundings. This could explain the consistent pulling away of the street curb that is very pronounced along Canal Street, with the soil towards the middle of the street where the canal used to be compacting and settling more quickly than the soil of the older buildings and sidewalks dipping down further, thus resulting in the shoulder of the road separating from the sidewalk.

While it is not surprising to see the façades of older, historic buildings have cracks and faults, it is more interesting to note that the newer brick of the ground-level façade already has a similar crack running down the side.

One of my most surprising discoveries was how even very recent urban features like roads or brick walls succumbed to the natural processes that sought to rend everything out of square. Brand new brick facades cracked along the same lines of old cracks, while new brick and pavement shifted along lines prescribed by old maps. Additionally, this cracking tends to be parallel to the direction of Canal Street. Given how the houses are arranged all next to each other, it is possible that the soil on which the buildings were built settled together as a unit, resulting in cracks in the pavement and buildings parallel to Canal Street.

1814 map of Bulfinch Triangle, with Causeway Street built on top of the Mill Pond dam. Site boundaries for this project are marked in blue, parking lots in black, and brick walkways with significant deformation marked in red. Salt deposits on roads are white lines. Map reproduction courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library. [5]

The dam wall of Mill Pond was expanded into a strip of island much earlier than the pond was filled in, with the wall itself becoming Causeway Street. Given the older age and possibly sounder construction of the dam wall and nearby strip of land, I expected to see some differences between Causeway and the rest of the site in terms of geography. It may have been better maintained because it was a major road for cars, but perhaps the lack of interesting features was more a sign of more settled, solid ground than the rest of Bulfinch Triangle, which is marked by strange geometry.

Given that parking lots, especially ones these cramped, do not generally have to deal with substantial wear and tear from cars driving over them, it is safe to assume that these cracks are due to a combination of the shifting soil underneath being unable to properly support the weight of the cars ans water seeping and freezing into the cracks.

Some of the old building spaces have been turned into parking lots, no doubt in response to the sports stadium nearby. It is interesting to note that all of these are universally clogged with snow and feature cracked, strained asphalt. The piled snow suggests a combination of the fact that there is no place for the snow to move onto, that those spots retain cold, and that they are seen as not particularly useful by people. The cracks in the parking lot asphalt implies that the soil cannot properly support the weight of vehicles in the long term, and the cracks probably trap water that turns into ice, creating more cracks. Considering that Bulfinch Triangle was built long before the advent of automobiles and the streets have not changed layout since it was first made, it is possible that they were not designed in mind to hold up automobiles.

One of many pools of water formed along the side of the road without a place to drain to.

As filled land, the issue of water and water drainage becomes a confounding factor. Bulfinch Triangle appears to have few storm drains and grates upon initial inspection, and even after only a light layer of snow, there puddles formed where the asphalt had retained water without it properly draining. According to Spirn, “the concrete, stone, brick, and asphalt of pavement and buildings cap the city’s surface with a waterproof seal,” [6] a phenomenon exacerbated by the scarcity of storm drains. She asserts on the other hand that “the compaction of city soils retards water infiltration and drainage,” [7] so it is possible that, because of the landfill soil of Bulfinch Triangle, the water is deliberately directed elsewhere by the streets and drained there. This seems to be in conflict with many other sites, which prioritize draining water even at the cost of redundant grates, while Bulfinch Triangle seems only sparsely populated by means of removing water. In fact, many of the streets have a continuous, two foot wide streak of salt down the middle, where water has collected after melting and deposited the road salt onto the surface.

Line of salt produced by water collecting in the middle of the road.

While it is perhaps a matter of maintenance, poor water drainage could also hint as to why the site lacks plant life aside from human-planted trees. The lack of available soil, combined with how the water leaves road salt in the places that it is present may contribute to only pre-planted trees and older, extant ones from being able to survive. Spirn notes that “the density of city soils is one of the primary reasons for the demise of trees,” [8] of which the little available soil in Bulfinch Triangle is very much compacted. The few trees planted there have had soil brought in for the trees to subsist on, or otherwise the extant trees are quite mature enough to be paved over and survive on the existing soil. I noted these observations during the cold of winter, however, and I am curious to see if there would be more “volunteer” plants in the nooks and crannies of the site when the weather is more hospitable.

As Boston has grown over time, its landmass has increased by having the nearby water filled in and built upon. While Bulfinch Triangle is a particularly dramatic example of this, the process has happened all throughout Boston, as the maps show a gradual expansion outwards. This process of building onto the ocean will no doubt continue in the future, and urban planners need to take into consideration the implications of their work. The site features clear, though subtle, indicators that it was not held to as high standards in planning out its consequences as would be possible today. More broadly, the development of land must take into account both the history of a location (both natural and manmade) and the future problems and possible purposes. The initial damming of Mill Pond did not account for the possibility of the pond fouling or the mill becoming ineffective, and the Triangle itself shows signs of uneven settling of the underlying soil. Bulfinch Triangle appears to have weathered natural disturbances without major problems, but it demonstrates how the nature of a site continues to disrupt it hundreds of years in the future. While humans can drastically change the landscape and the environment, we cannot halt the natural every day processes as a result of our actions. Therefore, when creating changes and building developments, we need to be collectively aware of the possible consequences of plans for the future.

[1] Bulfinch, Charles. Manuscript plan of the Bulfinch Triangle, Boston MA. 1807. Map. maps.bpl.org/id/10513

[2] Lodge, John. A chart of the coast of New England, from Beverly to Scituate harbor, including the ports of Boston and Salem. Baldwin, Robert, 1774. Map. maps.bpl.org/id/10915

[3] Howe, Jeffery. “Boston: History of the Landfills.” A Digital Archive of American Architecture. www.bc.edu/bc_org/avp/cas/fnart/fa267/bos_fill2.html

[4] Spirn, Anne. The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design. New York: Basic Books, 1984, 100.

[5] Hales, John Goves. Map of Boston in the state of Massachusetts. 1814. Map. maps.bpl.org/id/12926. Annotations by author.

[6] Spirn, 130.

[7] Spirn, 104.

[8] Spirn, 105.

Bibliography

Bulfinch, Charles. Manuscript plan of the Bulfinch Triangle, Boston MA. 1807. Map. maps.bpl.org/id/10513

Hales, John Groves. Map of Boston in the state of Massachusetts. 1814. Map. maps.bpl.org/id/12926

Howe, Jeffery. "Boston: History of the Landfills." A Digital Archive of American Architecture. www.bc.edu/bc_org/avp/cas/fnart/fa267/bos_fill2.html

Lodge, John. A chart of the coast of New England, from Beverly to Scituate harbor, including the ports of Boston and Salem. Baldwin, Robert, 1774. Map. maps.pbl.org/id/10915

Spirn, Anne. The Granit Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design. New York: Basic Books, 1984.