Natural Processes

Following the Fill: Artificial Land in a Natural System

Introduction

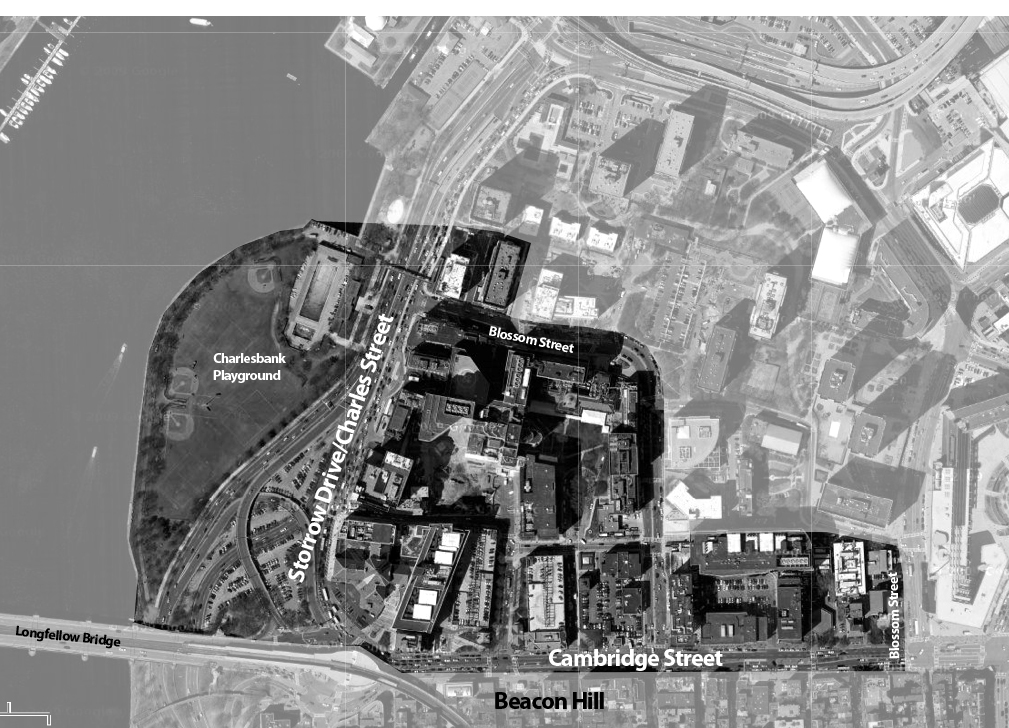

The West End is a very interesting case study for examining the impact of natural processes, particularly the area shown in the site map below, because only about half of its landmass is actually natural. Over the course of 75 years, areas of the Charles River bank were filled in to create adjacent manmade land. While nature was the underlying force behind the original land’s development, the manmade land was driven by the economics of construction instead. Natural forces, particularly topography, plant life, and water flow, shaped each kind of land very differently. The discrepancies that resulted from this clash of land origins played a major role in the characteristics of this site and are still shaping it today.

[base map from Google Earth]

Topography and Early Development

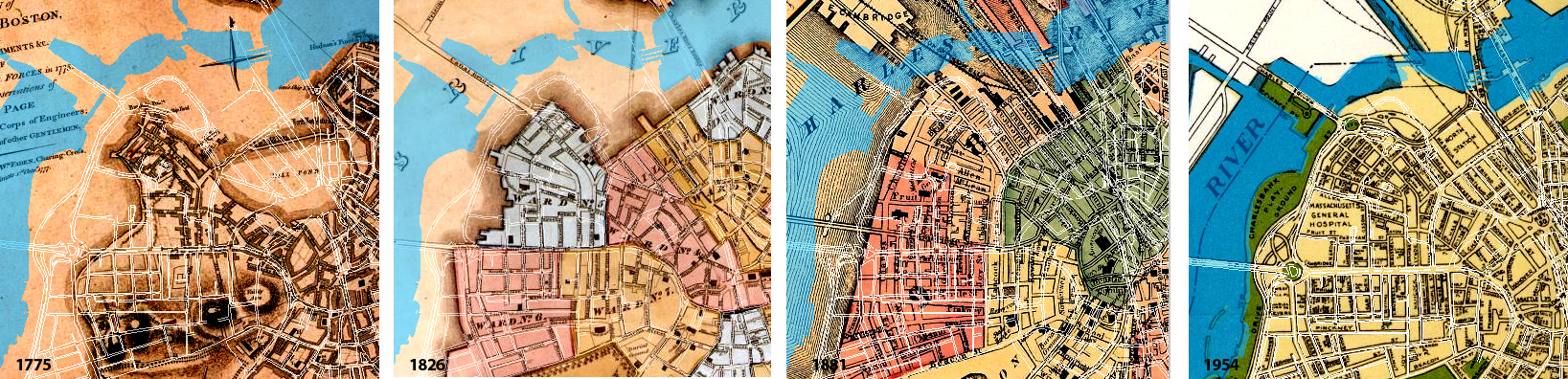

The West End was once a small landmass extending from the base of the Tri-Mountain peaks in Beacon Hill until its gentle slope reached the shore of the Charles River. A similar landform extending from the same peaks was settled as the North End, and the bay separating the two points became known as Mill Pond.

As a result Boston’s topography, almost all roads into the West End contained some degree of a kink. Roads connecting the West End to the North End had to curve around Mill Pond, and by 1775 the majority of the West End was settled between the shore of the pond and this main road. To access to the West End from mainland Massachusetts, roads spanning the neck of the Boston peninsula followed the natural curve around the contours of Beacon Hill until they reached Barton’s Point at the very tip of the landmass.

[historical map series from The Boston Atlas, from left to right: 1775 Town of Boston Entrenchments, 1826 Annin and Smith, 1881 Mitchell Boston Overview, 1954 City Planning Department]

[1953 topography map. West End Project Report, Boston Housing Authority]

By the early 19th century, the natural topographical logic that influenced the settlement and street pattern of the original West End was dismissed for the manmade land, which infill operations, mapped above, reclaimed from the Charles River. Since it was not created by nature or governed by topography, the new land’s development instead took on the more desirable characteristics of nearby Beacon Hill. The roughly gridded streets of Beacon Hill were emulated or extended on the West End side of Cambridge Street, the road dividing the two neighborhoods. The break between the kinked, topographically driven street pattern and efficient, gridded blocks desired on the manmade land was considered further evidence for the need to radically replan the area in the 1960s, and most of the area was demolished.

Today, one of the only indications of the original West End topography is the discernable slope of Cambridge Street from Staniford Street down to about North Anderson Street. The two surviving churches of the old West End, built in the 1750s, are still perched at the top of this slope. The land west of North Anderson is the land reclaimed from the harbor, land that was built to be flat and therefore inexpensive to construct and construct upon.

Signs of Life

After the West End’s redevelopment was completed, the vast majority of uses on the site were devoted to an upper-middle class demographic. As a result, the modern West End suffers from what Grady Clay would call an excessive amount of turf. Prestigious private institutions like Mass General Hospital or luxury industries like hotels and residential towers thrive on the illusion of order and exclusivity, an image they exert through their landscaping. At first glance, the site displays nature as a manicured “geometry of territoriality” (Clay, 153). If the pruned hedges and planter beds aren’t conveying the message “someone owns this property” loudly enough, the wrought iron gate surrounding the bed certainly is.

It seems like almost every scrap of unbuilt land is accounted for, and has become part of someone’s groundskeeping routine. Even the few tree-lined streets in the West End grow dutifully away from building facades. The pattern can’t be explained by wind or solar stimuli, since the trees don’t bend in a consistent direction. Further examination of the trunks shows four to six large branches removed from each one by human means. This is just one example of the expensive landscaping practices that are required to maintain this artificial nature. But despite all the care that these private turfs require, in many cases the nature they contain certainly isn’t flourishing. However, on the few corners and back alleys where ownership is more ambiguous, pioneer and volunteer plant life are beginning to take back the landscape.

[Site photos, taken February 28, 2010]

While late winter isn’t the best time to evaluate the health of plant life, it is clearly evident which trees grew naturally in the West End and which trees were artificially introduced for neighborhood aesthetics or as part of someone’s turf. For example, the tree in the foreground of the following photograph is, by far, one of the largest street trees on Cambridge Street. The awkwardness of its positioning in the middle of a Mass General sidewalk, the clumsy attempt to contain it in a planter bed, and the girth of the trunk all suggest that this tree grew on the site before the hospital was ever built. Older trees such as this prove that the typically subpar soil quality of filled land reclaimed from the harbor is not a factor impeding plant growth.

[Site photo, taken February 28, 2010]

This older street tree has fortunately been preserved responsibly with a large, gravel covered soil bed to keep the roots’ access to air and water intact. The younger street trees in the following set of images, however, are not growing nearly as well. Even though they were transplanted over six years ago, as shown by the 2003 BWSC Orthophoto, these trees have yet to fill out. Successive buds stack on top of one another, translating to a growth rate of about a quarter of an inch per year. Since their planting conditions appear to allow adequate levels of air and water to reach the roots, this stagnated growth is likely a direct reflection of the massive amount of traffic that surrounds this median and the air pollutants that become trapped in the Cambridge Street street canyon.

[Left: Google Streetview. Right: site photo, taken February 28, 2010]

While a hardier species of tree may be able to survive the poor air quality, this image provides evidence that this median was not landscaped with the harsh growing conditions in mind. Comparing the Spring 2007 Google Streetview Image with the current conditions, it is clear that while a variety of species were planted on this median, some survived much better than others, resulting in large patches of dirt that were once planted. Rather than designing for pure aesthetic, this median should have been designed according to the site-specific growing conditions. Consequentially, the trees on this median will likely only have a lifespan of ten years or less (Spirn, 171).

The majority of the West End was landscaped for aesthetics in this way, without concern for the growing conditions each species is best suited for. An enormous amount of effort and resources are required to keep them alive, while species from the local urban biome grow autonomously on immediately adjacent sites.

[Site photo, taken February 21, 2010]

The photo above shows a private courtyard, complete with ornamental fencing but lacking any sign of life in its planting pots. The row of shrubs along the right wall is the owner’s attempt to give the courtyard some visual privacy from the street, but their growth is too slow and sparse to accomplish this. However, a moss species is able to creep up one of the concrete walls even though winter has barely passed. Had local plant life been used in this garden instead of fragile, foreign species, the dense growth of the local vegetation would create far more privacy for this courtyard while consuming fewer resources. While this courtyard is a small-scale example, the image illustrates a largely upheld trend not only in the West End, but generally across the country as well. Plant life incompatible with the site’s natural forces is continuously planted and wastefully maintained in a privatized landscape, rather than designing with nature to harness the adaptive power of the urban biome.

Changing Shorelines

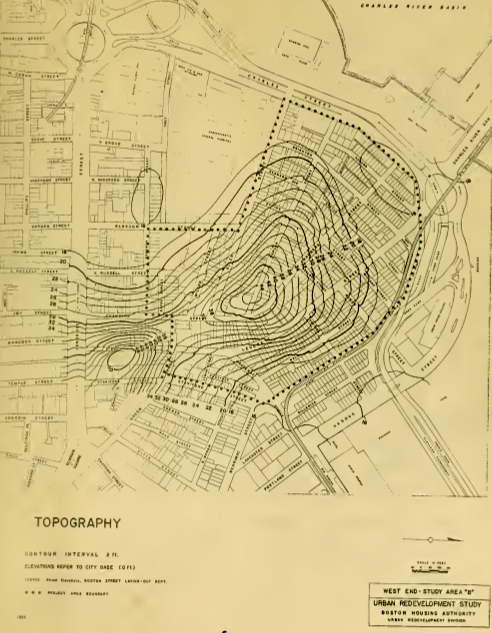

Despite the fact that at least half of the site was once below sea level, the modern West End seems extremely divorced from the Charles River. This is largely the impact of Storrow Drive. At its widest point, nine lanes of high-speed traffic separate the West End from its waterfront. To reach the shore, today’s pedestrians are only allotted one bridge to cross the highway in the course of its nearly half-mile span through the West End. Prior to this transformation, the site for Storrow Drive’s expansion was actually the Charles River Beach, as seen in the photo below (note the Lechmere Viaduct in the background of both images).

[Left: West End Museum archive, right site photo, taken February 21, 2010]

By the completion of Storrow Drive in 1951, the shoreline of the Charles River had been pushed over 1,500 feet away from its original location through the infill of land. An important side effect of this infill process today is the direct effect it has had on the flow of rainwater on the site. The original topography of the West End allowed for rainwater to follow the gradual slope of the land down to the River.

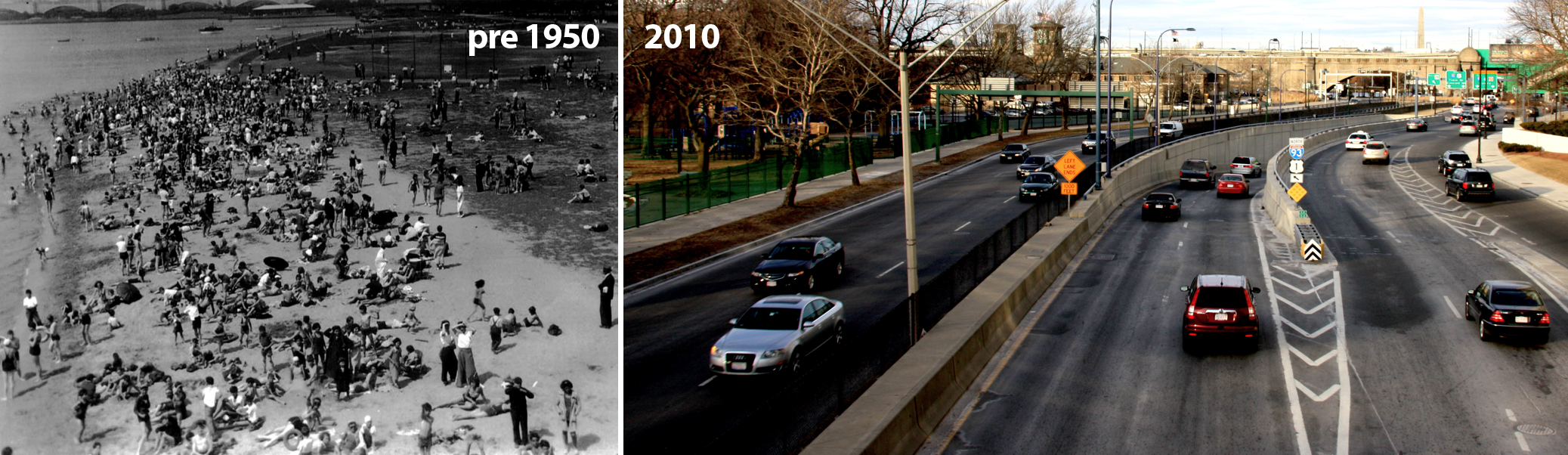

While that natural drainage system is still in effect for the West End’s original land, the new land was not designed to engage with this system. Not only does the manmade land not benefit from the topography-driven drainage, it is actually damaged by it. The new land interrupts the water’s path to the River because of it was filled to be as level as possible for construction purposes. As a result, the new land collects considerably more standing water than the original, sloped land, the effects of which are recorded in the pavement of the low-lying areas of the site. The photos below illustrate the damage the standing water can cause, particularly the alligatoring sidewalk cracks on the left.

[Site photos, taken February 28, 2010]

The water drainage problem is only exacerbated by the turfing phenomena described earlier. With the majority of the landscaped areas in the West End containing plants that are very fragile under local growing conditions, irrigation systems are required to maintain their growth, especially in the elevated areas that are shedding water downhill. Even if the species the planter bed contains happen to not require excess watering, an irrigation system is probably put in place regardless due to lack of awareness about the full spectrum of environmental issues that cause plants to die. Because the turf is so privatized, irrigation systems are implemented on an ad-hoc basis, and often inconveniently retrofitted in the case of the older land. For example, this photo is taken just 20 feet away from the private courtyard discussed earlier to show the damage it has caused to the public sidewalk over time.

[Site photo, taken February 28, 2010]

The drain pumps out the excess water once the irrigation is complete, creating a depression and radiating cracks, only for this water to crack the sidewalk again once it recollects as standing water on the low-lying land near the River. This unnecessary amount of damage allows the plants in the courtyard only a marginal level of growth. The consequences of turfing in terms of drainage needs and water flow add to the argument against forcibly proliferating inappropriate species of plant life in this manner.

Interrelation of Natural Systems

Without any doubt, the natural forces in effect on this site, including water flow and plant life among others, are interrelated to the point where affecting one area of the system is guaranteed to somehow influence the others down the line. In the case of the West End, the common link between these forces is the underlying role of the site’s topography, whether it’s natural or manmade. Dealing with the natural forces has undeniably caused some compounding of already complex problems, but precedents for environmentally responsible developments, such as the Woodlands, demonstrate that equally comprehensive solutions are available to solve issues such as water flow and erosion or the plant life of the metro-forest. The question of how the natural forces in cities may continue to shape the urban areas is answered in the human response to these problems.