Google. Retrieved from https://maps.google.com/maps?ct=reset&tab=ll

Coolidge Corner is home to one of the thriving, commercial hubs in the suburb of Brookline. Centered around the Green Line’s Coolidge Corner Station at the intersection of the major roads Harvard Street and Beacon Street, the area demonstrates an urban commercial setting, with numerous shops, restaurants and heavy traffic to match. Moving to streets past these two main roads reveals Coolidge Corner’s suburban residential backbone. Because the different land uses occur within such distinct areas in my relatively small site, the contrast and interplay between the commercial and residential spheres is heightened and can be easily tracked. The ways in which natural processes interact with the built environment varies depending on the location within the site. These processes are most evident in the pavement and trees; the former revealing Brookline’s uniform response to its urban ties and original topography and the latter showing distinguishable measures of its current mixed land use.

A Solid Foundation, A Cracking Surface

As revealed in Spooner’s early map of Brookline, the city was originally a hamlet of Boston, nested along the Muddy River; it was even referred to as “Muddy River” until 1705 when it became its own independent town.¹ Because my site rests on original land, the region was able to be settled very early, unlike many parts of Boston which was originally underwater. Marshes and small rivers can be found east of my site’s boundaries, but Coolidge Corner has developed on relatively stable and flat land which proved attractive for early agricultural use. Thus the buildings hold their footing on the same type of foundation, resulting in an area that does not have many distinct breaks, differing surface levels or underground happenings.

However, the site does exhibit many signs of stress and wear on its surface, especially present in the pavement and curbs of the main roads. According to the terms defined and used by James Elkins in How to Use Your Eyes, Coolidge Corner shows various signs of raveling, shoving, and cracking.² Cars and people constantly flow through my site, primarily by means of Harvard Street and Beacon Street. As a bustling part of Brookline, Coolidge Corner experiences continuous crowding and many moments of stop-and-go traffic. These moments are worsened by the lack of traffic lights and regulated intersections and the multitude of four way stops and crosswalks. This, combined with natural weathering, results in perpetually worn-down streets mirroring those found in Boston.

Aside from the lights that regulate the main intersection (Harvard Street and Beacon Street), there are no other stop lights in the site. Harvard Street has very few stop lights even when including parts outside of my site’s boundaries. Instead the streets are full of crosswalks, each with a neon sign that reads “State Law Yield to Pedestrians” (Figure 1). Because the street is not regulated by lights and is, as a result, subject to the will of pedestrians, cars stop more randomly and arguably more often. At the very least, the process of slowing, stopping, and starting is more prevalent. The nature of this movement creates a perfect setting for distress in the road. The wheels of cars grip the pavement and cause shifting with each start and stop, and after many times, this motion causes noticeable dents and crinkles in the asphalt. Additionally, a contributing factor to the formation of cracks stems from the weather of the Northeast. New England’s tendency for on-going periods of snow, rain, and freezing temperatures creates the perfect conditions for freeze-thaw weathering. When water that seeps into small cracks in the ground freezes, it expands and forces the material to split, creating bigger gaps. These new spaces give water room to sink further into the pavement and cause more stress fractures from its repeated freeze-thaw expansion.

After the cracks form, the rampant traffic causes even more cracks; each time resulting in more intricate fragmentation and deeper potholes. Once the potholes are deepened and the fragments are loosened, wind becomes a key contributor to the weathering processes. The wind carries the detached pieces away, exposing a new, smooth canvas to become cracked once again. On windier days and especially at the large intersections prone to eddies, the debris from the cracks is displaced. The places of speckled cracking that resembles the speckled skin of reptiles (what Elkins’ calls “alligator cracking”) become prone to chips of pavement breaking off, exposing the interior layers of asphalt and causing loose gravel to accumulate by the curbs.³ An example of this, present in Figure 2, shows how this perpetual chipping away can lead to a gaping hole in the road. Harvard Street displays many of these potholes, which tend to branch off the patches of alligator cracking. The raveling has turned the roads into bumpy throughways.

Although this form of cracking is easily spotted, the roads also display long thin cracks that span the width of the street. These too are most likely the result from the combination of wear and tear from the traffic and the natural weathering from wind and water. These cracks cut into the streets and reveal their worn state, suggesting that either Brookline does not concern itself in the upkeep of its roads or that the distress is occurring more rapidly than the maintenance can mitigate. Because some areas, especially on Beacon Street, look much newer (still showing cracking on the edges but not cracks in the center of the street) I would guess that the latter is more likely to be the case. The number of patches and temporary repairs present on Harvard Street also show the town of Brookline’s effort to counteract the scarring on its streets (Figure 3). Construction processes resulting in partial road closures imply that the area’s condition is closely watched. Brookline, an affluent suburb, continually battles the natural declination of its roads. Coolidge Corner draws business and people to the town, and which more than likely contributes to the watchful care given to Harvard Street and Beacon Street.

Even so, the attentiveness seems to be limited to the area’s main roads, leaving out the more remote locations. One example, supportive of this mindset, is seen in and around the alley along Waldo Street. Despite the apparent lack of traffic-caused erosion, this inlet shows many uneven irregularities. The pooling of water in Figure 4 caught my eye and revealed noticeable shifts in the pavement. I cannot say for sure what forces, if not general wear from weather and traffic, could cause such deep impressions in the road. However, it remains unsurprising that the area receives little care from the residents of Brookline, given the absence of people and stores that wander and inhabit the street. Still, the various puddles and dents shout for attention as you walk past the dingy alley.

Sidewalks throughout my site contain discontinuities that reflect shifts in the earth as well. One memorable spot located on the sidewalk of Stearns Road has a small wedge of cracked asphalt in the middle of concrete paths (Figure 5). The reason for this break is not clear, but it reveals how much more vulnerable asphalt is to stress when compared to a material such as concrete. Another notable change in sidewalk material can be seen on Green Street; this too appears to be asphalt. The strip contains some cracks and rough edges but has fared better than the asphalt seen on Stearns Road, and is generally smooth.

In addition to the worn surfaces of the sidewalk, the curbs show many signs of wear as well. The edges of the curbs that were once sharp are now full of grooves and waves and are smooth to the touch (Figure 6). Smooth curvy curbs are in spread throughout my site, but are especially present in areas prone to wind. Weathering from the wind has gradually deformed the curbs. In the open space where Harvard Street, Green Street and a tall, arched entrance to an alleyway meet, wind forms a circular motion. I visited my site on a day when local weather reports showed 11 mph south winds for the day. At this intersection point, air blew in east and west directions and grew stronger as it funneled into the arched entry way. In addition to the alleyway tunnel, the area seemed particularly windy possibly due to downslope winds from the roof of the S. S. Pierce building. This building is very tall especially when compared to the surrounding single story shops. The roof also is triangular, resembling a mountain slope and angled down toward the street. In The Granite Garden, Spirn diagrams the ways buildings can redirect winds, and the particular placement at this intersection expresses many different reactions to the wind.⁴

A Variety of Trees

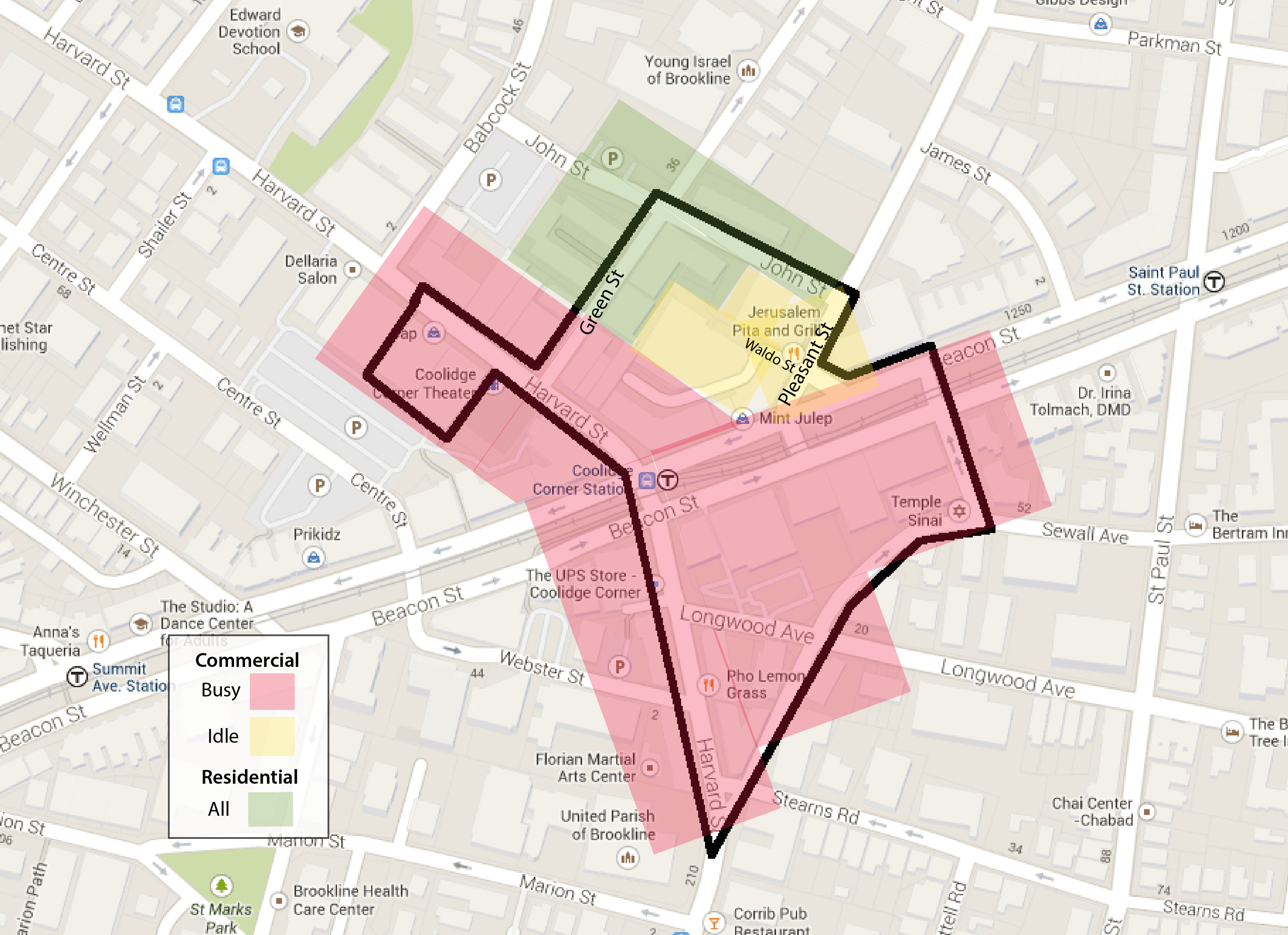

These grey regions in my site convey a sense of uniformity and continuity regardless of heterogeneity in land use. At any given point, the same irregularities are visible, and the differences between subareas become blurred, almost indecipherable. Though the surface may not reveal much diversity, the plant life shows a multifaceted space, split up into three distinct factions. I have defined three spaces in my site, classified first by the land use and then by the amount of traffic received (the map at the top of the page marks these areas). These three areas are especially highlighted in the following pairs of streets: Harvard and Beacon Street, Pleasant and Waldo Street, and Green and John Street. These pairs represent the following classifications respectively: busy commercial, idle commercial, and residential.

Looking at early maps reveals the long-standing importance and history of Harvard Street. This major road is shown on maps as early as 1822, so its later role as the commercial center of Brookline is no surprise.⁵ Harvard Street’s intersection with Beacon Street and its development into a commercial center influences both the reason for and survival rate of its trees. Typical of most urban centers, the trees of this region line the storefronts and, due to lack of space, are forced to grow in tiny rectangles of soil. The inviting appearance of trees lining a boulevard is thought to attract potential customers. Ideally, these trees would reflect a healthy and beautiful scene, but the hostile environments found in cities can often adversely affect their growth. As Spirn explains in The Granite Garden, “trees of a single species are planted equidistant in rows to achieve a uniform visual effect,” an act that tends to place the importance of choosing a species in its aesthetic appearance rather than in its viability.⁶ Thus the trees and vegetation in my site that were not intentionally planted and instead are indigenous to the region and naturally occurring, have survived and prospered, unlike the trees planted as decoration.

The decorative trees on Harvard Street and Beacon Street serve the same purpose of attracting people to Coolidge Corner’s shops, but each street has a different effect on their ability to survive. Harvard Street’s trees generally face a less friendly environment, most inhabiting plots of soil half the size of the ones on Beacon Street (Figure 7 and Figure 8). The available sunlight also differs between the two sites. Beacon Street is much wider to account for the Green Line running through its middle; therefore, the buildings that surround the trees do not hinder the reception of light as much as the buildings on the much narrower Harvard Street, which shroud some of the trees in darkness. Furthermore, a decorative wireframe fence or a raised curb surrounds the soil of many Beacon Street trees, providing more protection from wind erosion and foot traffic. It seems as though more care and attention were put into Beacon Street’s plant placement when compared to the plant placement on Harvard Street, where most trees were very carelessly planted next to street lamps and various traffic signs (Figure 9). Trees have either grown away or around impeding obtrusions or fought for space and forcing the signs and posts to slant. As expected, the Beacon Street trees tend to dwarf their counterparts and appear healthier overall.

Narrowing the focus to trees on Harvard Street alone reveals how significant changes can occur due to subtle changes in location. For example, the west-facing trees fair worse off than their east-facing equivalents; their clustering branches shorter, thinner, and chopped off at a much lower height to cope with impeding street signs. Their bud scars appear in closer intervals and their size is smaller. Recent construction around these trees has shown just how small a space the trees have to inhabit and alludes to the city’s possible rethinking of the placement of their trees.

The second pair of streets bears virtually no resemblance to the first. When you turn the corner onto Pleasant Street, suddenly there is not a tree in sight. Though this area contains a few businesses, it is apparent that it mainly serves as a transitional space between the busy commercial throughway and the quiet residential community. Since the region typically lacks crowds of people, it is left barren. These streets were skipped when planting trees in the livelier parts of Coolidge Corner (Figure 10). Support for this lies in Spirn’s explanation in The Granite Garden that urban plant life is a heavily aesthetic decision that becomes a very expensive addition to a city.⁷ Intentional planting of trees in a city usually stems from people wanting to “add” or “reincorporate” nature into the city. Though the inclusion of plants is sometimes sparked by environmental concerns for better air quality and wind barriers, many trees that adorn commercial streets (and are not given larger green spaces) are placed for the facade. As a result, the incorporation of plant life on empty roads like Pleasant Street and Waldo Street would be wasteful and superfluous because no one would see it. My site further supports this conclusion because trees and other plants are only found in the more popular areas and not in the more remote parts. Sewall Avenue (another street in the southern region of my site) even transitions from having trees to not having trees based on these principles. Plants are left out of specific parts of a city, leaving places like Waldo Street devoid of both human and plant life, home only to concrete.

Lastly, the residential region of my site reveals the most successful plant environment. The plants in this region include both indigenous and introduced species. Plants intentionally included in residential land are still placed for aesthetic purposes; like businesses in commercial areas, apartment complexes want people to flock to their beautifully landscaped residences. However, residential areas also exhibit plants that are placed and cared for by specific individuals. People continue to desire the beauty of nature, so they plant smaller bushes and potted plants along their doorways and windowsills. They tend these plants, and because of the personal care, the plants typically fare better. The trees on Green Street and John Street are huge and seem to have been more successful than the trees lining the boulevards of the shops because they have far more room to grow. They reach significantly greater heights and contain many more branches (Figure 11). These trees are not planted in the narrow space between sidewalk and street but are instead introduced into miniature plant communities. The trees tower over the neighboring buildings and are significantly older than the other trees in my site.

Some of the huge, older trees easily predate the apartments and parking lots around them. Along John Street a parking lot has formed around three towering trees with thick trunks. These trees are longstanding and have a firm hold in the earth. This parking lot is the one of the only places in my site where nature has proven strong enough to interfere with the pavement. As previously stated, most cracks in the pavement have been the result of weathering from inanimate forces of wind and water as well as human interaction; however, the roots of the two trees guarding the entrance to this parking lot have caused noticeable shifts and cracks in the ground (Figure 12). Their roots seem to have extended under the sidewalk, creating hilly waves in the surface and stress fractures in the parking spaces. Though cracking and level shifts in the asphalt has occurred, the parking lot has caused the trees stress, too. The tree on the left’s roots have moved closer to the surface around the surrounding parking space (Figure 13). The addition of the parking lot has obviously transformed the habitat into a hazardous region. As Spirn states, “the survival rate and life span of urban plants can…often be enhanced dramatically by a slight improvement of a single factor in their habitat.”⁸ Conversely, a new suffocating layer of asphalt that inhibits its ability to collect water causes the tree to respond in great lengths.

A chain-linked fence surrounds encloses the parking lot from a neighboring alley. This fence has become the home to many plants. Vine-like weeds have woven in between the links and have provided sprouted many leaves (Figure 14). The fence has a sporadic state of rusted metal and new metal parts, meaning that it is composed of parts that are not all from the original fence. Repairs and replacements in the fence imply that the plants may have at one point overtaken the fence. Currently, the areas of fence nearby larger plants are bent and angled. Once again nature is seemingly fighting back with the built environment.

The disparity between the commercial region’s trees and residential region’s trees is astounding. Though the land in Brookline was settled all at once, the trees located in the residential sphere have been given the chance to become deeply rooted in the soil and grow over many years. Because some of these trees have been able to grow for hundreds of years, they have reached much greater heights than other areas of the site. The hostile environments seen in Harvard Street and Beacon Street clearly account for the stunted growth of their trees, but it is likely that the trees in front of the shops are also much younger than the trees seen in front of the apartment complexes. Spirn states that because entire streets can go through “massive plantings of a single species [they are susceptible to losing] most of [their] trees within a decade.”⁹ With this in mind, it is unlikely that the trees on Harvard and Beacon Street have remained the same for the past hundred years. Because the trees there inhabit absurdly small plots, they probably have had to be replanted many times.

These areas of study – the forces that mold the street and sidewalk surfaces and the interaction between the city and its trees – give way to a larger emergent idea: that there is a complex relationship between the site, its inhabitants, and the natural land which it occupies, and that this relationship dictates the natural and artificial processes which ultimately shape the area. The regular displays of distress and wear within the pavement and roads point to the central commercial purpose of the area and the more “urban” aspect of the site, as well as to geological changes in the land on which the site rests. The stark contrast between the qualities of trees within the three subsections of the site suggests differing modes of interaction between a city and its environment. These result from the role, perceived or indirect, of nature in the lives of the city’s inhabitants. These interactions range from complete indifference to a forced relationship simply for commercially aesthetic purposes to the much more mutual relationship apparent in the sites more residential or “suburban” area. Coolidge Corner, like many suburban commercial centers, squeezes contrasting environments into one mosaicked location, serving as an ideal model for the natural processes that take place in and shape cities. The dramatic contrast between spaces serves to make each individual space easier to study, as its reactions become more apparent. As a result, many of these observations can be made in other suburbs as well as in major cities.

Notes

A.E. Spooner Del, The Town of Brookline, 1822, (Brookline Historical Society and Brookline Engineering Department, 1945) map.

2. James Elkins, How to Use Your Eyes, (New York: Routledge, 2000), 28-33.

3. Elkins, How to Use Your Eyes, 28.

4. Anne Whiston Spirn, The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design, (New York: Basic Books, 1984), 66.

5. A.E. Spooner Del, The Town of Brookline, map.

6. Anne Whiston Spirn, The Granite Garden,179.

7. Ibid, 175-182.

8. Ibid, 185.

9. Ibid, 180.

Bibliography

Elkins, James. How to Use Your Eyes. New York: Routledge, 2000. 28-33.

Spirn, Anne Whiston. The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design. New York: Basic Books, 1984.

Spooner, A.E. The Town of Brookline 1822. Brookline Historical Society and Brookline Engineering Department, 1945.