Source:Brookline, MA. (17 February 2014).Google Maps.

Google. Retrieved from https://maps.google.com/maps?ct=reset&tab=ll

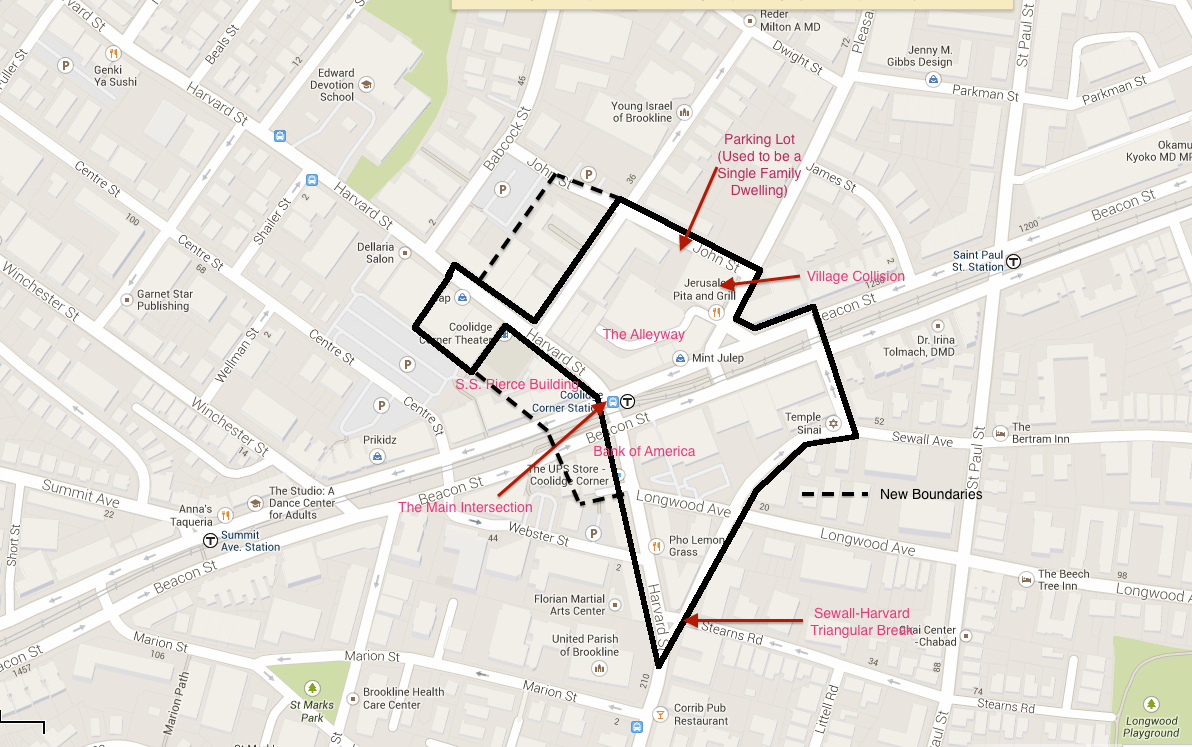

Visiting Coolidge Corner today reveals the longstanding dichotomous relationship between the residential and commercial sectors. These opposing forces are trying to inhabit the same space, vying for control but ultimately forced into forming an adaptive coexistence. Over time my site has changed from a sparsely populated, entirely residential terrain to a location occupied primarily by offices, stores, and restaurants. This change was prompted by the introduction of the electric trolley which is characterized by Jackson in Crabgrass Frontier as “a revolutionary advance in transportation technology,” an invention that dramatically altered the towns surrounding major cities across America.¹ Sam Bass Warner coined the term “streetcar suburbs” to describe this phenomenon of rapid development and expansion that impacted cities like Brookline, Massachusetts.² As the commercial sphere—originating at the intersection of Harvard Street and Beacon Street—encroached further onto residential territory, it gradually pushed the starting line for homes and apartments further back. The buildings themselves have evolved over the years as well. Just as apartments replaced homes, national franchises have overtaken local and regional shops. Interestingly buildings have typically maintained their purpose and have instead only changed their respective company. Traces of the hasty growth that occurred in Coolidge Corner and the destructive consequences imposed onto preexisting homes are present today and imply that in the early days of commercial evolution people did not realize just how drastic the transition would affect the residents that had already been living in the area.

Early Roads and Odd Breaks

Source: Photo taken April 2014.

Marked paths began popping up on maps in the late 1600s.³ The unconventional intersection of Sewall Avenue and Harvard Street, the region’s first two streets, is noticeable today and is what originally drew my attention to the site. Because these two winding roads formed when the area was a wide open, rural town, the streets intersect at a point, creating a triangular in-between space. The current buildings’ shapes conform to this break, which was formed in the 17th century (Figure 1). After the streetcar’s introduction to Beacon Street sparked commercial development in the area, detached dwellings with surrounding lawns and backyards were replaced by expansive brick storefronts that extended largely across the entire lot. Because the Sewall-Harvard break created a triangular property, the shape of the new structures formed a V-shape in order to take advantage of as much space as possible.

Recently while walking along Harvard Street toward the Sewall Avenue intersecting point, I saw another break between two building complexes that lie in the triangular property space. Between these two structures, a gap about four inches wide runs straight through from one side to the other. The building on the south side is taller and peering into the gap reveals that its north facing wall contains a grid of windows, indicating that the taller building was built prior to the smaller one (Figure 2). Referring to historical maps shows this inverted triangular lot remained uninhabited for a long time; by 1897 the triangle was cut into thirds, with two lots at the larger base region of the triangle and one lot on the point side.⁴ The two lots on the base each contained one home while the point region was left barren. A map from 1913 still shows the two homes on the northern region, but also shows a large V-shape brick complex at the triangle’s point.⁵ The placement of the windows that are still present on this brick structure makes sense, because at the time of the building’s construction there was a larger space to view. In fact, during this time, one could probably gaze out of the higher windows and spot the iconic S. S. Pierce Building at the Coolidge Corner intersection. This view did not last for long because by 1927, the two houses had been torn down and replaced by another massive structure which ran nearly right up against the side of the first building.⁶

Source: Photo taken April 2014.

The inclusion of these windows hint at a peculiar mindset of the first developers from the early 1900s. It signals that whoever built the building thought they would be purposeful and ultimately worth the effort and expense, suggesting that the person did not expect the two homes to be soon replaced by another commercial building that would block the windows’ views entirely. Up until this time, few homes had suffered the axe of big business taking over their properties. Though massive storefronts started popping up ever since the streetcar arrived in the 1880s, they were generally constructed on undeveloped land or on land that had previously been under commercial use. The stores had not started cutting so deeply into the residential sphere and away from the Coolidge Corner intersection. This lack of foresight also implies a hasty thought process in development. As Jackson explains, the potential of the streetcar sent “property values...rising rapidly in anticipation of a change in land use. Speculators bought such properties in the hopes that the houses could be torn down to make room for commercial development.”⁷ Owners of open land either quickly built stores themselves or sold to businessmen. The latter seems more prevalent because the names of owners in 1913 compared to those in 1927 shows a transition from single names to names with “et al Trs.”⁸ Businesspeople catalyzed the transformation of Coolidge Corner and proved detrimental to the residential sector as they tore down homes. Still, these people did not initially realize the extent of success the commercial sphere would gain nor its power to easily remove and overtake residences.

New Name, Same Face

Source: Photo taken April 2014.

Though the commercial areas of Coolidge Corner have dominated Harvard Street and Beacon Street property lots whose buildings have stayed nearly the same since 1965 and have driven most residences off the boundaries of my site, the companies themselves have changed over the years. Interestingly enough, as the stores were taken over by new companies (usually by national chains) they tended to maintain their original use (Figure 3). The S. S. Pierce building, for instance, whose building footprint shows up on the northwest corner of the main intersection as early as 1913, originally took the lot of the Coolidge Brothers’ small grocery store that had served the area in the 19th century.⁹ Now this building houses a large Walgreens pharmacy which is similar not only in that it is a store, but also in the kind of store. Directly opposite, in the southeast corner, a grand building towers high over the intersection and is topped with an American flag. As noted on a map from 1913, the building was occupied by the Boulevard Trust Company, a local bank. Staying true to its identity, the corner building is now inhabited by a Bank of America.¹⁰

Waldo Street leads to the area behind the Beacon Street storefronts, an area that since 1913 has been associated with automobiles when the first garage entered my site. By the late 1920s the garage had extended and an adjacent garage had popped up. As detailed by a map from 1965, the second garage later became an auto sales and service with the original garage acting as an auto repair and parking.¹¹ Currently the auto sales and service building is a Village Collision, a local repair service which as stated on their company website did not take over the building until 1970, and the auto repair and parking garage doors are boarded up with wood and the old windows with brick (Figure 4).¹² This automobile driven area shows its age in its worn buildings with stained brick, chipping paint, and distressed wood.

Source: Photo taken April 2014.

Source: Photo taken April 2014.

Much as the S. S. Pierce and Boulevard Trust Company buildings have traditionally been, respectively, a pharmacy and a bank, the space that the garages occupy has been continually associated with cars for an entire century, even if the companies themselves changed over the years. The recycling of places with the same function says something about the specific program that is planned in every architectural design and how each structure fits a distinct purpose. The large open spaces and high ceilings of the auto repair building as well as garage doors accessible for cars accounts for the services that occurred over the years. The wide flat area in the S. S. Pierce store made for a perfect transition into a pharmacy with multiple aisles filled with various products, and a bank’s specific needs of a teller space and a vault make it adaptable to any bank enterprise. Buildings are tailored to certain services and, as seen in my site, have been through many iterations of the “same service, new company” paradigm.

National chain corporations and various regional and local shops have cycled through my site as well. The arrival of chain stores indicates the commercial success Coolidge Corner achieved during the 20th century and the location’s appeal drew in brand names - including Starbucks, Peet’s Coffee, The Body Shop, CVS Pharmacy, Panera Bread, Yogurtland, and Gamestop - that congregated on the east facing side of Harvard Street north of Beacon Street. These franchises are all found in the strip of stores on the northeast corner of the main intersection. This mass was one of the first major commercial structures built after Beacon Street’s trolley line was created; thus, it had a longer time to develop the commercial identity associated with the closely-packed stores.

Source: Photo taken April 2014.

This strip has also fared better because of its location on the main intersection, especially when compared to the more recent line of storefronts that can be found by simply taking a left onto Pleasant Street. These slightly younger stores, added when the new garage was built, now contribute to a shabbier part of my site with their run-down wooden frames and deserted states. Although they were made with more uniformity - indicated by their homogenous colorful wooden exteriors adorned with large photos of smiling families - than the ones on Beacon Street and Harvard Street, their suffering condition either causes or is caused by their lack of foot traffic and neglected surroundings (Figure 5). Since they rest just outside of the alleyway entrance and are attached to the auto repair shop, itself in very poor condition (at first glance easily assumed abandoned), their lack of success in Coolidge Corner most likely results from their surroundings (Figure 6).

Commercial Conquests and Residential Woes

Source: Photo taken April 2014.

Source: Photo taken April 2014.

The Village Collision, the alley, and the Pleasant Street storefronts compose a darker side of Coolidge Corner’s transformation into a commercial center. Together, these places form a run-down layer that lies in between the thriving commercial sections on the main roads and the pristine residences found further back. The floundering stores and their overall dilapidated appearance have proven unsightly to their neighboring apartments. A huge brick wall separating the flats from the alley marks an effort on behalf of the residential sphere to mask the unappealing commercial sphere (Figure 7). Towering roughly fifteen feet, the wall encloses the backyards of the apartments and completely shields the view of the run-down alleyway . The brick wall is one example of passive resistance to the displeasing parts resulting from the rapid growth of stores. Still, the windows from the higher-story rooms see straight into the dirty alley and the boarded-up, abandoned garage bins of the stores.

Since the streetcar’s appearance, the dwellings in my site and their residents have been fighting a losing battle. Their properties have been bought up, torn down, replaced, and pushed back. Even where the land use has been lucky enough to remain residential, the space still rings different because the detached dwellings are now contiguous apartments (Figure 8). A stark example of a loss for the residential sector can be seen in a small parking lot wedged between the Village Collision and the John Street apartments—the space that used to hold the longest standing single family home in my site. The home (appearing on maps from 1897 to 1969) had been the only remaining structure from 1897 and, for this reason, its destruction marks a great casualty(Figure 9). Trees dot the space in areas that originally surrounded the house, traces of the building they used to adorn. It is not difficult to visualize the small home, set far back from the sidewalk, behind the two colossal trees in front that framed the entrance. Though the home is long gone, as Hayden says in The Power of Place , places that no longer exist are significant and should “still be considered a place, if only to register the importance of loss and explain it has been damaged by careless development.”¹³ This image represents Coolidge Corner’s original identity: a small suburb of Boston, full of dwellings that stood alone on large lots. The trees all extend past the heights of the neighboring buildings, serving as a reminder that the area is far older than its buildings.

Source: Left top: Atlas of the Town of Brookline 1897, map. Left bottom: Insurance Maps of Brookline, Revised to 1965, map. Right: Photo taken April 2014.

The fate of Coolidge Corner lies in these trends that have taken precedent over the 20th century. While visiting the parking lot, a woman came up to me and let me know that the spot (among others off my site) had just been bought up by a company planning to develop on nearby open areas. This company is likely to be one of many picking up the slack, and continuing the commercial growth of the region and leading to the indisputable invasion of more local residences in the near future. However, this infiltration has created two sides to the story, and they are fighting for dominance in the area. The flourishing commercial scene of Coolidge Corner is a facade, expressing only the good parts of the prosperous development. Behind these storefronts lies the space of true territorial war that comes with rapid development in any city across the country. This is the area where battles are won and lost, where homes are destroyed, where walls are erected in defense. The uprooting of homes and the failure of small businesses is inevitable in this cycle. Only time will tell if the bad effects of commercial development will ultimately outweigh the prosperity and popularity it brings the region.

Notes

1. Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 114.

2.Sam Bass Warner, Streetcar Suburbs: The Process of Growth in Boston, 1870-1900 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1962), vii-x.

3.Theodore F. Jones, Muddy River in 1667 (Brookline, Massachusetts: Brookline Historical Society, 1923), map.

4.Atlas of the Town of Brookline 1897, Plate C. (French & Bryant, 1897), map.

5.Atlas of the Town of Brookline, Norfolk County Massachusetts, 1913, Plates 13 and 14. (G.W. Bromley and Co, 1913), map.

6.Atlas of the Town of Brookline 1927, Plates 13 and 14. (G.W. Bromley and Co, 1927), map.

7.Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier, 90.

8.Atlas of the Town of Brookline 1927, map.

9.Atlas of the Town of Brookline 1913, map.

10.Ibid.

11.Insurance Maps of Brookline, Massachusetts: Volume One, Revised to 1965 (New York: Sanborn Map Company, 1957) Accessed from MIT Rotch Library.

12."Collision Center - Boston, MA - Village Automotive Group- Boston, MA - Village Automotive Group.” Village Automotive Group, 2014, http://www.villageautomotive.com/about-us/about-village-automotive-group/collision-center.

13.Dolores Hayden, The Power of Place (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1995), 18.

Bibliography

Atlas of the Town of Brookline 1897, Plate C. French & Bryant, 1897. Accessed online from WardMaps LLC 2014.

Atlas of the Town of Brookline 1927, Plates 13 and 14. G.W. Bromley and Co, 1927. Accessed online from WardMaps LLC 2014.

Atlas of the Town of Brookline, Norfolk County Massachusetts, 1913, Plates 13 and 14. G.W. Bromley and Co, 1913. Accessed online from WardMaps LLC 2014.

Clay, Grady. Close-Up: How to Read the American City. Chicago IL: The University of Chicago Press, 1980.

"Collision Center - Boston, MA - Village Automotive Group- Boston, MA - Village Automotive Group." Village Automotive Group 2014, http://www.villageautomotive.com/about-us/about-village-automotive-group/collision-center (accessed April 21, 2014).

Coolidge Corner: Past-Present-Future. Boston, Massachusetts: Hewitt Publishing Company: 1926.

Hayden, Dolores. The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1995.

Insurance Maps of Brookline, Massachusetts: Volume One, Revised to 1965. New York: Sanborn Map Company, 1957. Accessed from MIT Rotch Library.

Jackson, Kenneth T. Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Jones, Theodore F. Muddy River in 1667. Brookline, MA: Brookline Historical Society, 1923. Photo taken from Brookline Public Library.

Spirn, Anne Whiston. The Language of Landscape. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1998.

Warner, Sam Bass. Streetcar Suburbs: The Process of Growth in Boston, 1870-1900. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1962.