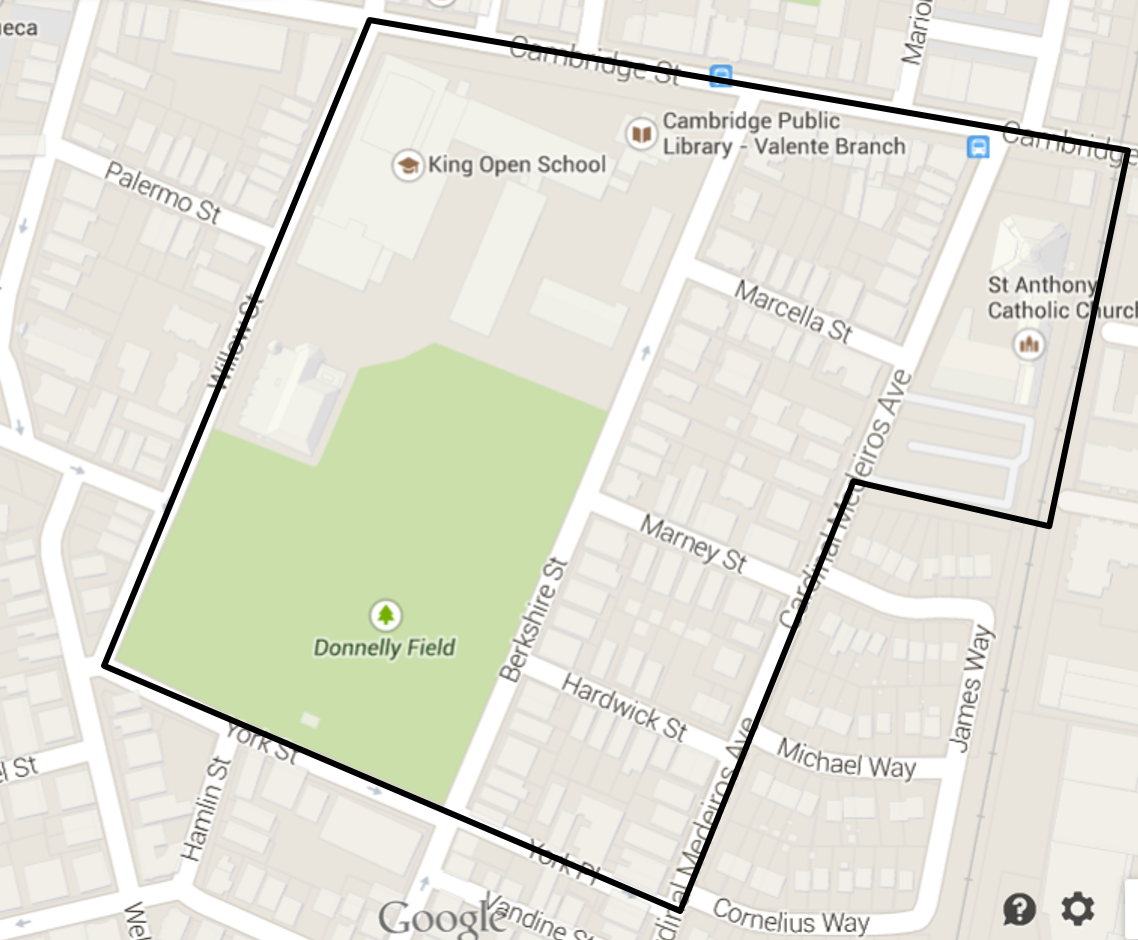

Figure 1: Map of my site, image from Google Maps, 2015

Figure 1: Map of my site, image from Google Maps, 2015

In our heads, mankind tends to draw a line between urban landscape and nature, separating them as two distinct things. However, this is an inaccurate view of the world. The city exists within nature and is shaped by its processes. My site, as outlined on the map above, is no exception. Its location on the mainland of Cambridge means that the changes to this site over time have been quite different than in the majority of the city surrounding it. The water flow in the area is almost entirely regulated by built infrastructure, a far cry from its original state. Unlike in many parts of the city, strong wind is not constant irritation here. Only by the field could the wind be described as more than a gentle breeze. The plant and animal life in the area is definitely the most obvious appearance of nature and natural processes in the neighborhood. As most of the trees and plants have been deliberately cultivated, they show signs of how people would like nature to appear in the city. In spite of the deliberate planting, the trees still point out the prevailing processes in the area. There is often a conflict between having natural plant life and other urban infrastructure, though, a tension that is inherent in urban landscapes. This tension exists in regards to animal life as well. The city is not simply inhabited by humans, a fact that people simultaneously enjoy and dislike. Although people look at a city and think that the landscape and conditions are predominantly controlled by man, natural processes have shaped the area from the beginning and will continue to do so long after the city is gone.

Environmental History

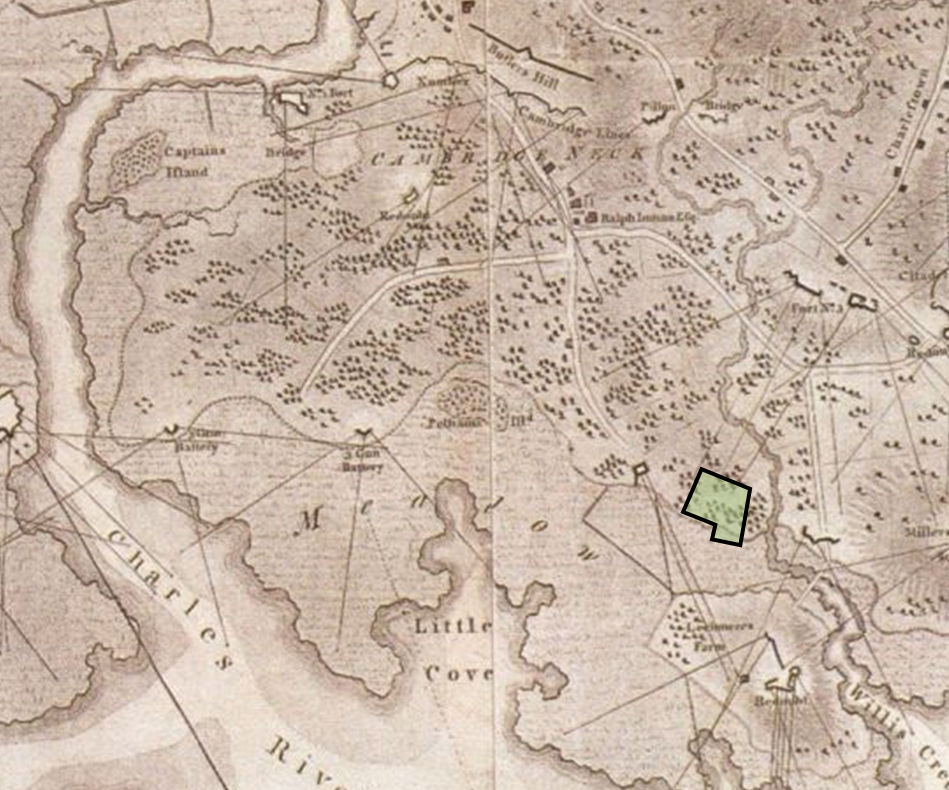

The land that this site was built on appears to have been on higher ground adjacent to a meadow. As the historical map shows, the site is relatively near a creek that no longer exists, as well as a hill. The site itself, however, is quite flat, as it appears to have been for centuries. It is not located on top of an old swamp or filled land, unlike much of the rest of Boston and Cambridge. This is highlighted in a historical map of the city area from 1775-76 shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: This map shows the site location before the area was developed. From my best guess, the site was located on the high ground by the meadow and the creek. The area is not denoted as swampland on this map. Map source: Pelham, 1777 from Krieger, 1999.

Figure 2: This map shows the site location before the area was developed. From my best guess, the site was located on the high ground by the meadow and the creek. The area is not denoted as swampland on this map. Map source: Pelham, 1777 from Krieger, 1999.

Fortunately for those who live in this site, this means that the buildings and land is much less prone to sinking or flooding. Once the land in Cambridge began to be filled in, a canal was constructed right along the edge of the site, likely because of the location along the edge of the meadow and higher ground. The canal’s path perfectly explains how Cardinal Medeiros and the rest of the neighborhood came to be constructed on a different grid pattern than the rest of East Cambridge: the streets follow the line of the old canal. This can be seen in Figure 3 which shows a map from 1848. The canal has since been filled in, but this neighborhood’s streets still mark its old location.

Figure 3: This map from 1848 show the parallel paths of an old canal and a street that seems to read “Dock Road”. I believe this so-called Dock Road is the first iteration of what is now Cardinal Medeiros Avenue. The rest of the site has been highlighted to show its historic location. Map source: Dearborn, 1848-49 from Krieger, 1999.

Figure 3: This map from 1848 show the parallel paths of an old canal and a street that seems to read “Dock Road”. I believe this so-called Dock Road is the first iteration of what is now Cardinal Medeiros Avenue. The rest of the site has been highlighted to show its historic location. Map source: Dearborn, 1848-49 from Krieger, 1999.

Water Processes

Although this area is not on filled land, as can be discovered from the historical maps, it was near a creek and a canal for a number of years. As was discussed, the path of the canal likely led to the structure of the grid for this site. However, other than this detail, the nearby water most likely had little influence on the buildings in the area. After all, most of the housing was developed after the natural water disappeared from surface maps. Though the site is not over a historic stream, it is now on top of a manmade stream: the sewer system. The many manholes that are found in this area attest to the fact that the sewer system is running beneath the streets, providing water and taking away waste. This system is a necessary attempt to exert control over the water flow in a city; otherwise the infrastructure of the neighborhood would cause flooding after rainstorms and drought the rest of the time.

Figure 4: Two manhole covers provide access to the sewer system running underneath Cardinal Medeiros Avenue.

Figure 4: Two manhole covers provide access to the sewer system running underneath Cardinal Medeiros Avenue.

To counter this danger, there is surprisingly good drainage for rain and snowmelt in this neighborhood. This system must easily handle the increased runoff due to the high percentage of paved land. Addressing the runoff itself, some of the drains were labeled by plaques stating that they drain directly into the Charles River. This indicates that city officials have been considering the effects of the runoff from the surrounding areas on the overall ecosystem of the Charles River. Hopefully residents also consider this before allowing chemicals and other waste to run into the drains. The emotional appeal to help the fish affected may help people take the extra care to protect the water, instead of disregarding natural processes and acting in a manner that is most convenient for themselves in the short term. In spite of all attempts to control the water flow in the area, we are dependent on the actions of many individuals and the processes of plants and animals that are out of our control.

Figure 5: Plaques near drains request better water habits of residents to prevent toxic runoff from entering the larger ecosystem. The small fish engraving calls attention to the creatures that could be affected if this request is ignored.

Figure 5: Plaques near drains request better water habits of residents to prevent toxic runoff from entering the larger ecosystem. The small fish engraving calls attention to the creatures that could be affected if this request is ignored.

While the drainage and sewer system fit well with the climate of the area, I was surprised at the lack of peaked roofs in the neighborhood. Generally, in northern climates or areas with heavy rainfall buildings have peaked roofs to redirect the precipitation. However, in this area, the roofs are predominantly flat. This seems to be a style of building that disregards the climate of Boston. Perhaps this signifies a lack of care in designing the buildings or perhaps the rain and snow generally are not heavy enough to cause a problem. Because of the unusually heavy snowfall, I wonder if some of the roofs are leaking since flat roofs can cause the water to pool instead of draining off. If so, this would demonstrate a rather shortsighted plan for the residences in the neighborhood in regards to how natural process affect buildings over time.

Wind

One factor that is notoriously difficult to predict without being present on a site is the wind patterns and how they will affect buildings, landscapes, and pedestrians. There was a noticeable difference between this site and areas near campus: namely, the lack of strong wind. This observation may be the result of a coincidence based on the prevailing wind direction of the day, but it is equally likely that the lack of tall buildings in the area and the shorter streets keep the wind from being funneled strongly into the neighborhood. The only location where there was a more significant breeze was near the field. This is could be because the wind can flow without obstruction in this more open area. As a result, the pedestrian traffic is much more comfortable along streets that are not adjacent to the field in the winter. The opposite may be true in warmer weather. However, during colder seasons, the very design that makes the area an attractive place to walk prevents it from being comfortable.

Sunlight

Though we are not always consciously aware of the patterns of sunlight, these patterns do dramatically affect our surroundings. The trees and fallen snow can help us see the effect of the sun more easily. Many trees in the site show signs of asymmetric growth. This often is a result of the tree growing towards an area with more light. For example, in Figure 6, the tree is growing towards the southwest, where there is more sunlight.

Figure 6: This tree is growing asymmetrically as its upper branches reach towards the southwest where there is more sunlight.

Figure 6: This tree is growing asymmetrically as its upper branches reach towards the southwest where there is more sunlight.

Thus, the shape of trees can show where there is more light. This asymmetric growth can also be seen in the narrower streets. The trees along these paths have more branches higher up, reaching for the sun that shines above the buildings. Between these buildings, little sunlight reaches the ground. The trees on the wider streets do not show this same growth pattern.

Figure 7: The image on the left shows how trees on a narrow street only have branches that are up high, reaching for the sun. In contrast, the trees in the image on the right have grown wider and have more branches lower on their trunks.

Figure 7: The image on the left shows how trees on a narrow street only have branches that are up high, reaching for the sun. In contrast, the trees in the image on the right have grown wider and have more branches lower on their trunks.

Aside from the trees, the general lack of sun on these side streets was shown by the lack of snowmelt. Less snow had melted in these areas than on the wider streets or on the field. Although we generally do not consciously notice the patterns of the sun, they do have an effect on the microclimates of a neighborhood, as can be seen by the response of the trees and snow. We may have control over the climates inside of our buildings, but outside of the buildings, natural processes rule. If thought is put into the design and location of buildings and trees, we can influence the microclimates outside, but in small residential neighborhoods, this level of detailed planning is rare. Instead, people, animals, and plants make do with whatever conditions they find.

Sidewalks

More obvious to the casual pedestrian is the effect of tree roots on sidewalks. Predictably, by each and every street tree, the sidewalks are cracked or raised. There is little evidence of damage to the sidewalks anywhere else. Some of the sidewalk sections have been replaced by asphalt next to the trees, probably in areas where the damage became too severe.

Figure 8: The image on the left shows a section of sidewalk raised by tree roots. The edge is currently filled in with snow. In the image on the right is a section of sidewalk next to a street tree that has been replaced with asphalt.

Figure 8: The image on the left shows a section of sidewalk raised by tree roots. The edge is currently filled in with snow. In the image on the right is a section of sidewalk next to a street tree that has been replaced with asphalt.

This observation demonstrates the conflicting values that we try to reconcile in a city: the beauty and aesthetic of nature with the desire to have flat and straight paths. In our culture, we value trees and greenery, and street trees help to create a sense of beauty in an area. However, we equally value sidewalks and want these paths to be flat and crack-free. These two desires tend to conflict, as street trees cause cracks and bumps in sidewalks. Thus, street trees next to sidewalks illustrate the conflict in our cities between our idea of beautiful nature and functional infrastructure. We cannot control nature such that it does not impact our other infrastructure.

Overhead Wires

The overhead wires directly above street trees also demonstrate this conflict between functional infrastructure and nature. In this case, trees were planted directly below the wires, forcing utility companies to trim the branches to grow around the wires to prevent damage. Different placement of the trees may have been wiser, but for some reason, this placement was chosen and has been maintained. Aside from the conflict between competing values, this issue may also demonstrate a lack of true understanding of natural processes: perhaps people are simply not good at projecting plant growth into the future. Instead of understanding that plants and trees are dynamic and will change shape over time, perhaps people shortsightedly expect them to remain frozen, as most installed infrastructure in a city does.

Figure 9: This tree has been split in two as it is forced to grow around the overhead wires.

Figure 9: This tree has been split in two as it is forced to grow around the overhead wires.

Animal Life

Although we are in a city, there are still animals that share the space with us. Dogs and cats are animals that we generally invite to live with us. This site shows clear signs of pet owners in the area. I spotted both cat tracks and dog prints in freshly fallen snow, as shown below. We do not generally think that pets could have a large influence on natural processes, but they can. As Spirn explains in The Granite Garden, “Dog feces contribute to the bacterial contamination of urban runoff, which is equal to dilute sanitary sewage” (211). This is exactly the type of runoff that the plaques above the water drains discussed previously were attempting to avoid. Thanks to the snow, evidence of dog feces in multiple places around my site was easy to spot. It is clear that dog feces is a problem, since the park even provides bags for owners to use to dispose of their pet’s feces.

Figure 10: Owners clearly do not always diligently clean up after their pets, leaving feces behind to contaminate the paths and the eventual water runoff.

Figure 10: Owners clearly do not always diligently clean up after their pets, leaving feces behind to contaminate the paths and the eventual water runoff.

Aside from deliberately invited animals, cities are also home to many uninvited guests: some benign, some less pleasant. On the more pleasant side, I was excited to see songbirds perching in some of the trees along Cardinal Medeiros. Of these, I could identify Cardinals and Robins. There must be enough open space and different types of cover in the area to provide them shelter, something more typical of a residential neighborhood than a downtown area. Unfortunately, the good cover and food that attracts the birds also creates a good living environment for rats.

Figure 11: Rat tracks were found in the snow along the sidewalk in front of a house in my site.

Figure 11: Rat tracks were found in the snow along the sidewalk in front of a house in my site.

According to Spirn, “Each year, rats inflict property damage, and each year cities spend millions of dollars on rat control” (207-208). In spite of all of this expenditure, the rat problem remains. This aspect of nature simply is not easily controlled.

Conclusion

Humans may feel as though they are the manipulators of their environment, but this is only partially true. Underlying all of mankind’s “manipulations” are the natural processes that govern the world. These influences can be seen both on a large scale, as well as on the small scale within a certain site. In this predominately residential neighborhood in Cambridge, the very layout of the streets reflects the environmental history of the area. Man has created an infrastructure for water, attempting to prevent the issues that paving would otherwise cause and to avoid dumping toxic runoff into the larger ecosystem. Attempts to control the wind have been mostly neglected, with important implications for comfort. The trees and plant life, although many have been deliberately planted, in turn, takes a toll on the surrounding infrastructure as conflicting values trade off in the urban landscape. Animals can thrive in cities, as well, whether or not they have been invited. Humans try to harness the beauty of nature for their own designs, even though this sometimes creates conflict. They like to feel in control of the space that they live in. However, even though people look at a city and think that the landscape and conditions are predominantly controlled by man, natural processes have shaped the area from the beginning and will continue to do so long after the city is gone.

Bibliography

Spirn, Anne Whiston, The Granite Garden:Urban Nature and Human Design. New York: Basic Books, 1984.

Images:

All images by author unless otherwise noted.

Figure 1: Map from Google Maps 2015.

Figure 2: Map from Pelham, Henry, A Plan of Boston in New England with its Environs. London, 1777. Found in Krieger, Alex, David Cole, and Amy Turner, Mapping Boston. United States of America: The MIT Press, 1999.

Figure 3: Dearborn, Nathaniel, A new and complete Map of the City of Boston and Precincts including part of Charlestown, Cambridge, & Roxbury, From the best Authorities. Boston: Boston Directory, 1848-1849. Found in Krieger, Alex, David Cole, and Amy Turner, Mapping Boston. United States of America: The MIT Press, 1999.