The layers and traces of history are always around us. Whether in a rural setting where these layers are primarily shaped by nature, or in an urban setting where many of the layers tell a story of human activity, signs of the past can be found. These artifacts can be simple things, such as old buildings or trees that have been untouched for year. They could also be more complex or subtle signs of the past, hinting at larger social patterns. As Dolores Hayden discusses, the idea of a “place” or space has spatial, social and political connotations (14). On any site, there can be signs of any or all of these historical influences. My Cambridge Street site is mostly flat in terms of historical layers, yet there are traces and artifacts that point out the major physical changes that have given the area its current shape, as well as hint at the cultural background of the residents. However, new trends highlight a tension between the historic demographic of the neighborhood and new players who may be moving in and affecting changes. Will this area’s history be wiped clean as a new, gentrified layer attempts to take over or will this simply add a new dimension to the neighborhood?

Traces and Artifacts of Physical Changes

There are relatively few signs of the physical changes that occurred on my site earlier than the 1930s; however, there still are a few artifacts of the 1800s that can be found. The angle of Cardinal Medeiros Avenue as it meets up with Cambridge Street is an artifact of the old Canal that used to run alongside the street. As can be seen in the old maps of the site, this street, originally Dike Road, was built to run parallel to the canal, explaining why the road is not aligned with the other streets in nearby East Cambridge, or even with the railroad that still exists today.

Figure 1: Portland Street, Dike Road on this map by Nathaniel Dearborn, used to run parallel to the canal that connected the area to the Charles River. This alignment is different from the grid system used by East Cambridge in the right side of this map.

Figure 1: Portland Street, Dike Road on this map by Nathaniel Dearborn, used to run parallel to the canal that connected the area to the Charles River. This alignment is different from the grid system used by East Cambridge in the right side of this map.

The other artifact of nineteenth century history of this site is the existence of the Donnelly Park. This large open space was available to be made into parkland because the Binney family used to own a lot of land in the area, including my entire site. As part of an estate, this land was largely undeveloped and open. When the land was released from the estate and sold off, the city was able to set aside a sizable chunk as parkland, something that would have been difficult to do otherwise with the amount of development going on in the area at the time. Some potential artifacts of that time are the large trees that are found along the borders of the park. These trees look as though they are hundreds of years old and are the oldest trees found in the area by far. The longevity of these trees is only possible since this land was undeveloped originally and then held aside as parkland. Either deliberately planted or intentionally allowed to remain growing, these trees show the value that park curators placed on preserving nice trees in this area.

Figure 2:This tree is one of two or three old trees along the border of Donnelly Park. It looks as though these trees have been deliberately preserved for decades in this park.

Figure 2:This tree is one of two or three old trees along the border of Donnelly Park. It looks as though these trees have been deliberately preserved for decades in this park.

Once the rest of the land was sold off and opened up for use, it was developed quickly. Nearly all of the homes in the area were built between the 1900s and the 1930s. Some land use has changed since the 30s, but for the most part, residences have remained residences this whole time, making the site relatively flat in terms of historic development.

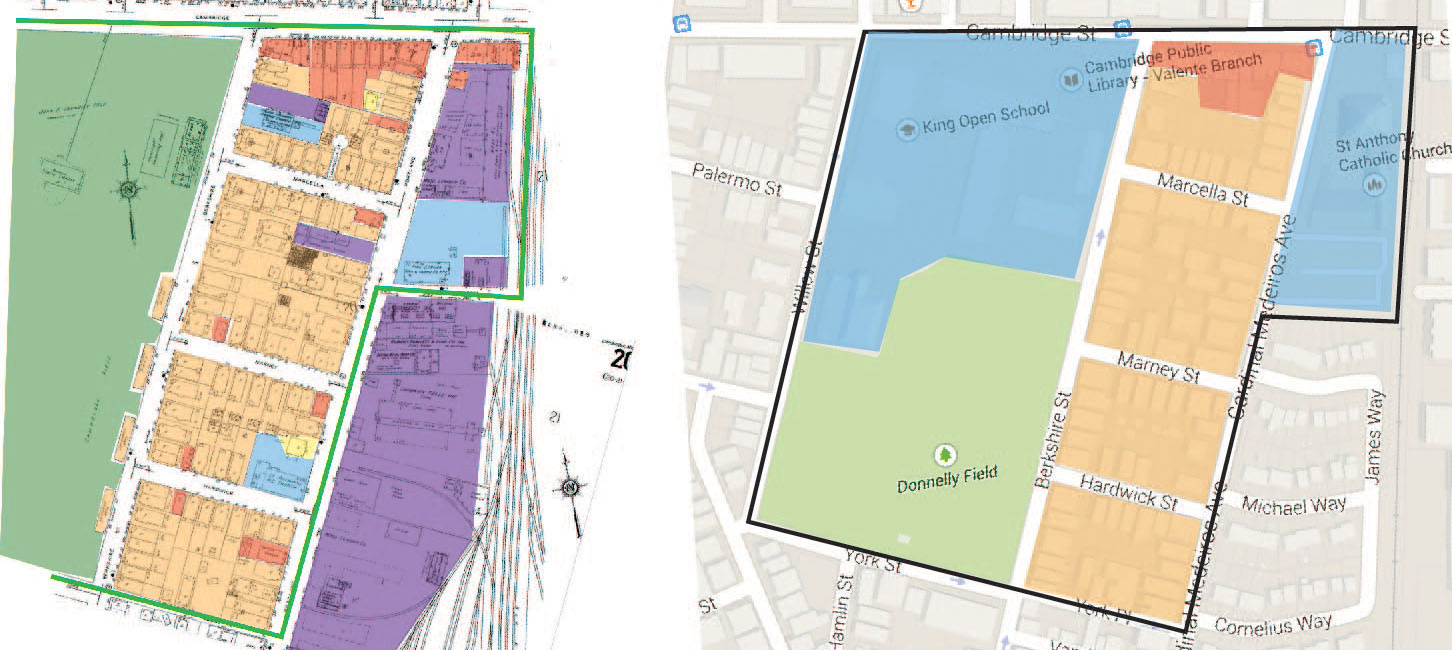

Figure 3:Very few of the buildings in the residential section between Cardinal Medeiros Ave and Berkshire Street have changed since the 1934 Sanborn map on the right when compared to the Google Maps 2015 image on the left. The few stores that were not along Cambridge Street have been converted into just residential buildings, St. Anthony’s Church has moved and the few “industrial” plots have been absorbed by the residences around them.

Figure 3:Very few of the buildings in the residential section between Cardinal Medeiros Ave and Berkshire Street have changed since the 1934 Sanborn map on the right when compared to the Google Maps 2015 image on the left. The few stores that were not along Cambridge Street have been converted into just residential buildings, St. Anthony’s Church has moved and the few “industrial” plots have been absorbed by the residences around them.

There are a few exceptions to this rule, though. The hall and bakery labeled on early maps along what is now Cardinal Medeiros Avenue have since been converted into residences. The “industrial” plots, mostly storage sites for the industry along the railroad, have been absorbed by the surrounding residences. These minor changes between the 1930s and today highlight the overall stability of the residential potion of the neighborhood over the past century. While the area around my site underwent more dramatic shifts, the physical structure of my site itself remained mostly unchanged.

The only other notable physical change that can be observed today is the movement of the churches in the area. This movement hints at changes in the population of the area around the site. For a brief period of time (seen only in the 1934 map), there was an Italian Calvary Baptist Church on the site. This is a fleeting influence, though, when compared to the impact of St. Anthony’s Catholic Church on the area. Over the century that this Portuguese Catholic church has been on my site, it has expanded and moved to a location with more space, though still within the boundaries of the site.

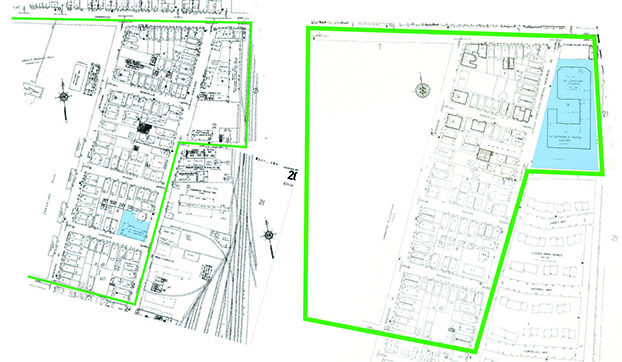

Figure 4: The Sanborn 1934 map on the left shows the original location of St. Anthony’s Church. In the 1996 Sanborn map on the right, the new location is shown. Only two blocks up from the original location, the church was able to expand to about four times its original size.

Figure 4: The Sanborn 1934 map on the left shows the original location of St. Anthony’s Church. In the 1996 Sanborn map on the right, the new location is shown. Only two blocks up from the original location, the church was able to expand to about four times its original size.

The old rectory is still standing, now a residence unattached to any religion. The old church no longer exists; instead, there is now a duplex on the plot of land that it once occupied. The new church building is much larger, with parking on site as well to reflect modern transportation needs. This artifact of a recent change (around the 80s) highlights the expansion of the Portuguese Catholics in the area. I believe that the fact that the new church building was located so close to the old site may mean that the location was an important factor for parishioners: they likely live in the surrounding area, meaning that my site would have a high concentration of members of St. Anthony’s Church.

Evidence of a Religious Neighborhood and the Influence of Portuguese Immigrants

Many artifacts point to the conclusion that the residents of this site are very religious and that the Portuguese Catholic community has had an important impact on the area. Aside from St. Anthony’s Church, which has been present on the site for over 100 year, there are many artifacts found on and near the residences that point towards Catholic beliefs and culture. Behind or near a number of apartment buildings, I saw religious shrines, many of them appearing to feature Mary. There were also a number of buildings that had beautifully painted tiles with religious themes. I saw paintings featuring Jesus, angles, and other scenes associated with Christianity.

Figure 5: These photographs were taken of various houses in the site. Pictured are three of the shrines found and three of the religious tile paintings seen near various building doors. These findings support the idea that this neighborhood has a strong Catholic influence.

Figure 5: These photographs were taken of various houses in the site. Pictured are three of the shrines found and three of the religious tile paintings seen near various building doors. These findings support the idea that this neighborhood has a strong Catholic influence.

These were found in a few different locations around the neighborhood and on many of the multi-family homes. While some of the members of these households may attend mass at the Irish Catholic church slightly outside of the boundaries of my site, many of them likely attend St. Anthony’s.

St. Anthony’s, aside from having a long existence in the area, clearly needed to expand, moving to a new, larger location about 30 years ago. This move occurred at a time when the Archbishop of Boston was Portuguese-American. His influence may have helped the Portuguese church complete its expansion in a predominantly Irish Catholic town. Archbishop Cardinal Medeiros’s influence is also clearly seen in the renaming of the street; Cardinal Medeiros Avenue was Portland Street all the way up to Cambridge Street until the 80s. This Cardinal must have had a large impact on the site, and probably the city as a whole since the city of Cambridge was willing to change the name of part of a street in his honor. This change occurred after his death, and so it was most likely meant as a memorial. The expansion of the church as well as the change in the name of the street in honor of a Portuguese-American Cardinal reflect the growing influence and power of the Portuguese immigrants in this area and how they rallied around their religion to express this power.

Racial Diversity

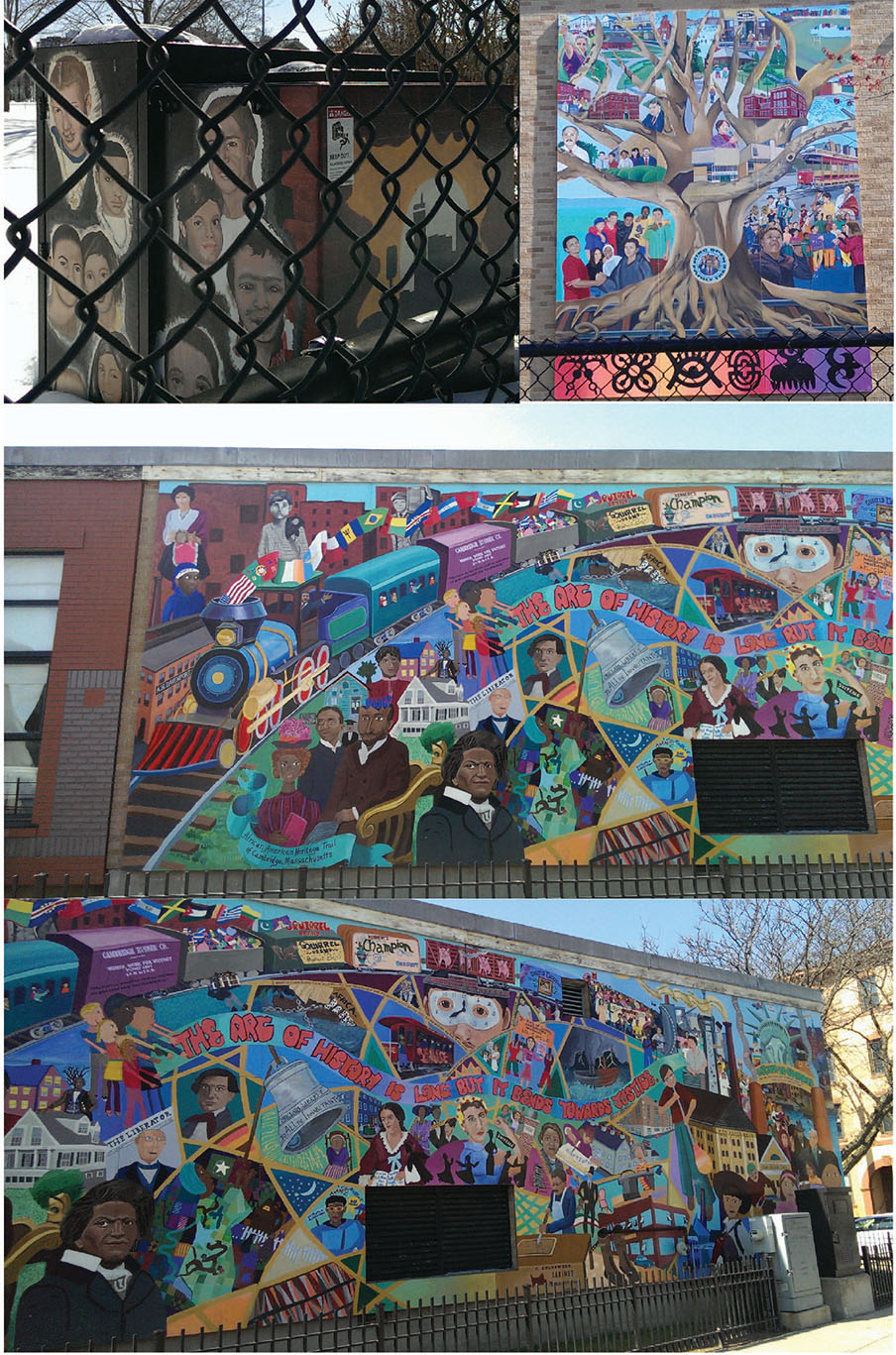

From the clear evidence of Portuguese immigrants in the area, it is easy to tell that this neighborhood was at least somewhat diverse. Based on other artifacts found on the site, though, it appears that this area was actually very racially diverse. Taking up part of Donnelly Park is King’s Open School. Based on signs advertising the school, this is a school that places a high emphasis on social justice and learning through diversity, quite possibly a reflection of the values of the neighborhood. The murals found on and around the school speak to these ideals and emphasize the importance of immigrants to the history of Cambridge.

Figure 6: These murals found around King’s Open School emphasize and celebrate diversity, justice, and the history of immigration in Cambridge.

Figure 6: These murals found around King’s Open School emphasize and celebrate diversity, justice, and the history of immigration in Cambridge.

This type of school and types of murals are not typically found in upper class, predominantly white neighborhoods. It is likely that, for the past century or so, the neighborhood has consisted of racially diverse, working class families. This seems consistent with the types of shops found along Cambridge Street on this site: Portuguese and Brazilian food stores, Italian Bakeries, and Barber salons appearing to specialize in black hair. From this evidence, it seems that the ethnic make-up of the past is a trend continuing into the present.

Trends into the Future

Although some artifacts point out that this neighborhood was inhabited by racially diverse working class families and still is today for the most part, it is unclear if this trend will continue into the future. There are some signs that the area may be undergoing gentrification. The most obvious signs of gentrification approaching the area actually comes from just outside of my site. Within the past 20 years, a small neighborhood of single family homes has been developed on land that used to be used for industrial purposes. Unlike the three-story, multi-family homes with small yards on my site, these houses are 1-2 stories with larger yards and appear to be for single families only. This seems like a style more reminiscent of the suburbs in an otherwise city-like area. It also implies the entry of a more wealthy demographic into the surrounding area.

Figure 7: These single family homes are relatively new, around 20 years old. They are across the street from the Cambridge Street site and have a completely different feel. This section seems much more suburban than the multifamily homes seen on my site.

Figure 7: These single family homes are relatively new, around 20 years old. They are across the street from the Cambridge Street site and have a completely different feel. This section seems much more suburban than the multifamily homes seen on my site.

On my site itself, many of the apartments sport new siding and are being advertised by larger relator companies instead of by individual landlords. Perhaps with these changes landlords are also attempting to attract more wealthy tenants into an area that is within walking distance of the more popular neighborhoods around Kendal and Inman Square. Some of the homes on the edges of the site also have a different architectural style with peaked roofs instead of flat roofs. This difference makes them stand out and seem nicer than the other apartments. They also have actual landscaping with expensive decorative stone walls in contrast to the rather overrun and unkempt yards of most of the homes on this site.

Figure 8: The house on the left has new siding, a nice stone wall and landscaping. The house on the right badly needs new paint and/or siding, barely has a path to the front door, and has an overgrown garden. These contrasting houses demonstrate the mixture of the older buildings in slight disrepair with the newly renovated buildings on the site.

Figure 8: The house on the left has new siding, a nice stone wall and landscaping. The house on the right badly needs new paint and/or siding, barely has a path to the front door, and has an overgrown garden. These contrasting houses demonstrate the mixture of the older buildings in slight disrepair with the newly renovated buildings on the site.

There are a mix of car types seen on the site as well. While most of the apartments have some form of parking, this is typically for 1-2 space only for a multi-family home. As a result, the vast majority of the cars compete for street parking. On these spaces, the cars ranged from smart cars, to old beaten up cars that barely run to the few newer-looking midrange quality cars. It seems that although the majority of the residents are less wealthy and own either smaller cars or old cars, a different demographic is moving in.

Figure 9: There is a range of small cars to larger, midrange quality cars found in the neighborhood. The majority of the cars, though, appear to be older models.

Figure 9: There is a range of small cars to larger, midrange quality cars found in the neighborhood. The majority of the cars, though, appear to be older models.

However, it is uncertain whether this trend will overtake the whole neighborhood. Although some apartments do show these signs, the majority do not. The majority are older buildings that are showing signs of wear and the dominant demographic still appears to be working class. Many mailboxes also are labeled with ethnic names, demonstrating that the diversity of the area has not decreased either. Only time will tell if a new gentrified layer will be added on top, perhaps consuming this site, and what effect, if any, this will have on the diversity of the neighborhood.

Conclusion

This Cambridge Street site has undergone many transformations: at first a swamp, then an estate with a factory on it, then a working class neighborhood near industry. Finally, as the industry moved out, the neighborhood demographics remained diverse and working class. In spite of all of these changes, the site is primarily composed of the residential layer built around the 1930s. However, some traces and artifacts of earlier times still exist. The shape of the land and old trees harken back to the times before residential development. Most of the traces and trends point to signs of diversity and a strong influence of the Roman Catholic Church over the past century. These influences have been relatively constant, from the evidence seen, and only minor changes have occurred on the site itself. It is unclear whether the signs of the beginning of gentrification in the area signal a new period of intense change, whether manifesting in physical changes or a demographic shift, or if these anomalies will simply remain anomalies.

Bibliography

Hayden, Dolores. The Power of Place: Urban Landscape as Public History. Cambridge Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1995. Web.

Ap. “CARDINAL MEDEIROS OF BOSTON DIES AFTER CORONARY BYPASS OPERATION.” The New York Times 18 Sept. 1983. NYTimes.com. Web. 26 Apr. 2015.

Images:

All photos by author unless otherwise noted

Figure 1: Dearborn, Nathaniel, A new and complete Map of the City of Boston and Precincts including part of Charlestown, Cambridge, & Roxbury, From the best Authorities. Boston: Boston Directory, 1848-1849. Found in Krieger, Alex, David Cole, and Amy Turner, Mapping Boston. United States of America: The MIT Press, 1999.

Figure 3: Map from Hales, John G, 1830. Found in Harvard University Library. http://ids.lib.harvard.edu/ids/view/46931239?buttons=y Accessed March 23, 2015.

Figure 3: Digital Sanborn Maps: Insurance Maps of Cambridge Volume 1. Sheet 21. New York: Sanborn-Perris Map Co. United. 1934.

Map from Google Maps 2015

Figure 4: Digital Sanborn Maps: Insurance Maps of Cambridge Volume 1. Sheet 21. New York: Sanborn-Perris Map Co. United. 1934.

Digital Sanborn Maps: Insurance Maps of Cambridge Volume 1. Sheets 7, 20. New York: Sanborn-Perris Map Co. United. 1996.