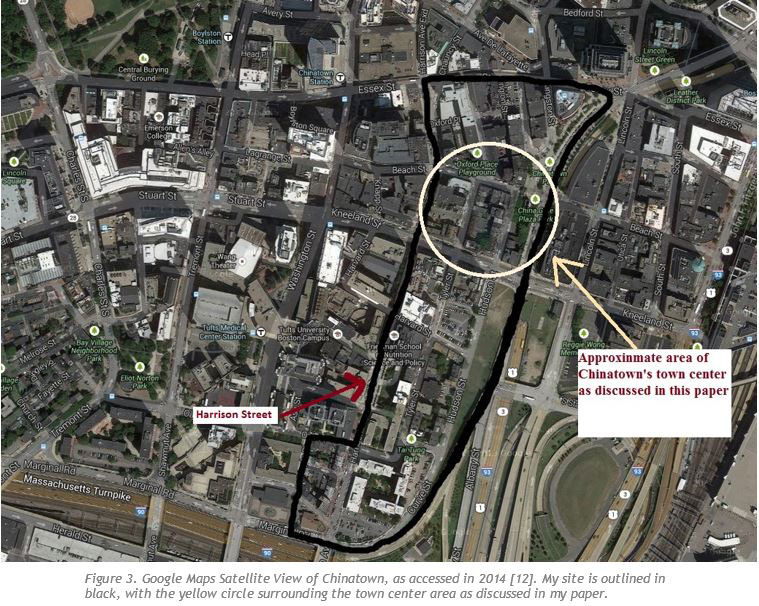

Boston’s Beach Street is known to most as Chinatown’s center and premier tourist destination, yet it contains a second subtle significance easily overlooked: in its name lies the most direct clue to Chinatown’s history. Rewind two centuries, and on the same site is a beach and a bay. The ramifications are still evident today. The filled landscape, shaped by water flow, plant growth, and wind patterns, wear down Chinatown’s manmade structures. While the town center is relatively responsive to these natural processes, the outskirts remain oblivious to nature’s course; this dichotomy creates a visible divide in infrastructure conditions between town center and outskirts. Ultimately, the ignorance in the outskirts poses health risks not only for Chinatown, but also for the entire city.

Historic Landscape: Beach and Bay

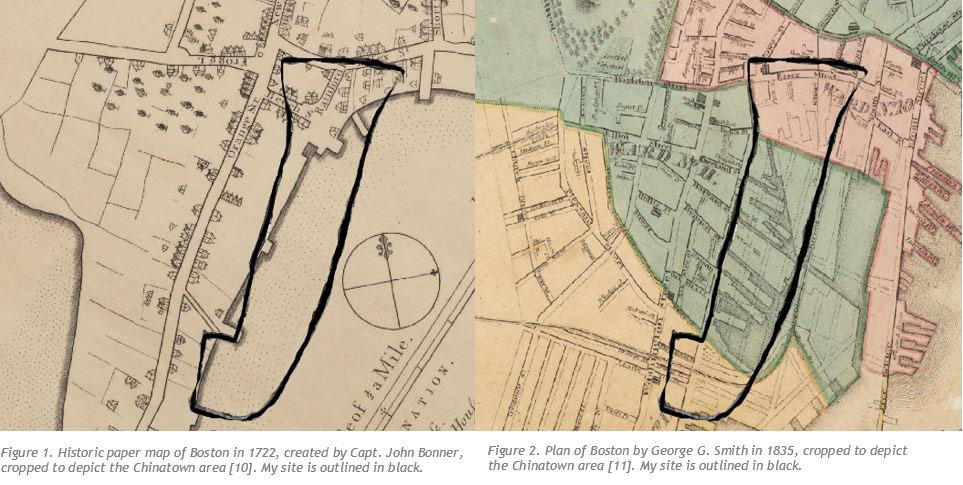

Originally a combination of beach and bay, the site of Chinatown was filled during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The 1830s featured an especially rapid plan for expansion (Figures 1 and 2). Chinatown is effectively flat; there are no hills or valleys. Street patterns, from the 1830s to today, are primarily a structured grid, likely because there are few natural obstacles on a filled piece of land.

Artificial land can be problematic for buildings’ foundations. One indicator is the relatively short height of Chinatown’s buildings compared to those of surrounding areas on natural land. Anne Spirn, in her book, The Granite Garden, suggests that while natural soil has been compacted for many years, filled land may lack this heavy compaction that is essential to supporting tall buildings [1]. In fact, in the outskirts, many of the mere four to five story buildings show signs of foundation settling. Cracks in walls, for example, are common in the brick homes lining Hudson and Harvard Streets (Figure 4). When soil in the foundation shifts, the homes’ foundation cannot sustain the rest of the structure, and portions of walls begin to slide out of place [2]. This phenomenon, perhaps triggered by the loose soil, is worsened by ongoing natural processes, as we will discuss in the following sections.

Figure 4.This home’s walls are cracking and settling. Darkened bricks beneath the window suggests that water wear is a likely culprit.

Figure 4.This home’s walls are cracking and settling. Darkened bricks beneath the window suggests that water wear is a likely culprit.

Water

Rain and snow, abundant in Chinatown, facilitate building foundation wear, erode roads, and pose pollution risks when improperly drained. Although these effects are common throughout Chinatown, they are especially prevalent and ignored in the residential outskirts. In town center, water is generally directed away from buildings. Many store entrances, such as the entrance to Eldo Cake House on Harrison Avenue, are above ground level (Figure 5). Sidewalks generally slope downward from buildings (Figure 7) and direct water to drains on the roads. A few blocks down from town center, however, homes' entrances are below ground level (Figure 6). Significant wear, likely due to water, is evident on the steps leading down to homes and on the bottoms of the doors (Figure 6). Sidewalks lack a slope. Pipes drain water that settle on the edges of buildings, exacerbating cracks on the walls (Figures 8 and 9). Unlike the central parts of Chinatown, the outskirts appear to lack active rehabilitation to prevent water from damaging building foundations and heightening foundation settlement.

Figure 5 (left). Steps keep water from entering Eldo Cake House. Figure 6 (right). These steps have substantially more wear than those in Figure 5, likely because water traverses these steps frequently.

Figure 5 (left). Steps keep water from entering Eldo Cake House. Figure 6 (right). These steps have substantially more wear than those in Figure 5, likely because water traverses these steps frequently.

Figure 7. Sidewalks slope towards the drain

Figure 7. Sidewalks slope towards the drain

Figure 8 (left). Ice is left to drop and melt by the building’s lower walls. Figure 9 (right). Broken pipe leaks water and damage the building wall.

Figure 8 (left). Ice is left to drop and melt by the building’s lower walls. Figure 9 (right). Broken pipe leaks water and damage the building wall.

Moreover, erosion in the less-maintained residential streets worsens travel conditions. Potholes are a common occurrence, especially in parallel parking spaces, where the road caves under the weight and rubbing of car wheels on the road surface (Figure 10). As cars repeatedly slide in to the same place, they mold the road so that the road slants towards the potholes. Water flows down the sloped road, carrying with it sediment and trash from the sidewalks. As discussed in Spirn’s in-class lectures, the mixture settles in the potholes, seeps under cracks, and enlarges potholes. Since some of the holes in Chinatown are over several inches deep, residents have likely left the problem idle for a long period of time, which can become a significant problem for drivers in Chinatown. Even worse, the toxins from the trash mixed in with the water could potentially seep into the soil underneath the pavement, posing health risks.

Figure 10. Water froze in this pothole created by cars frequenting the parking spot.

Figure 10. Water froze in this pothole created by cars frequenting the parking spot.

Yet a more immediate health danger lies in Chinatown’s drains. On Beach Street, drains have the occasional plastic cup or candy wrapper hovering, ready to fall inside. Equally worrying is the trash scattered through the sidewalks. Spirn writes about the problem in The Granite Garden, explaining that rainfall “sweeps the dirt and debris of the city streets into storm sewers, and with it heavy metals and other toxic materials, oil, and grease” [3]. The problem only worsens as we move towards the outskirts. In an alley leading away from Beach Street towards Downtown, we find drains completely clogged with trash (Figure 12). Not only is the drain effectively dysfunctional, but the trash toxins are drained to the Boston Harbor or Charles River (Figures 13 and 14), which pollutes the water supply both inside and outside of Chinatown. Effort in Chinatown to reduce the problem is minimal; collection of trash in drains suggests that they are not cleaned out regularly as they should be. Signs warn against dumping, but the trash loitering near the signs question their effectiveness (Figures 13 and 14). Chinatown’s oblivion to the effects of water flow, especially in the residential outskirts, not only damages its own buildings and streets, but also poses potential health risks for the greater Boston area.

Figure 12. Cars drive over this drain, which helps push sediment and trash into the drain and clog it.

Figure 12. Cars drive over this drain, which helps push sediment and trash into the drain and clog it.

Figure 13 (left). Drain with trash on its border dumps into the Boston Harbor. Figure 14 (right). Drain with trash on its border dumps into the Charles River.

Figure 13 (left). Drain with trash on its border dumps into the Boston Harbor. Figure 14 (right). Drain with trash on its border dumps into the Charles River.

Plants

Plants in the outskirts are largely ignored. Trees with soil pits barely larger than a few square feet line the streets of Hudson and Tyler. Their roots are entrenched in pavement and brick (Figure 15). Yet they seem fully adapted to survive. They arch away from buildings and hover over roads to capture sunlight (Figure 17). They demand space by dislodging the sidewalks with their roots, creating ripples in the brick pavement (Figure 16). Eventually, as discussed in Spirn’s lectures, tree roots can reach far enough to loosen the soil around homes’ foundations, speeding up any foundation settlement already occurring. Ironically, it may ironically be the residents and their homes that bear more harm. When plants are not cared for in cities, they will rebel.

Figure 15 (left). As this tree’s roots displace the bricks, the bricks embed themselves into the tree. Figure 16 (right). Tree roots pushing against the sidewalk leave cracks and ripples in the brick pavement.

Figure 15 (left). As this tree’s roots displace the bricks, the bricks embed themselves into the tree. Figure 16 (right). Tree roots pushing against the sidewalk leave cracks and ripples in the brick pavement.

Figure 17. This tree bends away from the homes on Hudson Street to absorb more sunlight.

Figure 17. This tree bends away from the homes on Hudson Street to absorb more sunlight.

An exception to this man and plant struggle is Tai Tung Village, on the south border of my site, between Curve Street and Harrison Avenue. There, oriental-style trees adorn the village (Figure 18). Deliberately grown and nurtured in expansive soil pits, they have prospered to peak over the buildings of Chinatown. Next to a school, a bush has grown to be larger than its counterparts because a vent emits warm air right above it. In return for the care, the plants also provide substantial shade and absorb solar energy. This helps alleviate the “urban heat island,” a phenomenon described in The Granite Garden, where cities are significant hotter than nearby countryside because “concrete, stone, brick, and asphalt…absorb heat more quickly and store it in greater quantities than the plants, soil, and water that make up forest, fields, and ponds” [4]. Tai Tung Village is a clear example of the benefits residents reap when they are mindful of natural processes in cities.

Figure 18. Oriental-style trees adorn Tai Tung Village

Figure 18. Oriental-style trees adorn Tai Tung Village

As we move towards city center, the symbiotic relationship between plants and human activities becomes more prominent. We find Asian-inspired plants, such as bamboo, which adorn Chinatown Park, right off Beach Street. On Beach Street we also see a set of trees grown in front of a painted wall building (Figure 19). Intentional or not, the trees camouflage with the painting, creating a magnificent landscape background for residents to enjoy. Still, not all green attempts are fully successful; in Chinatown Park, for example, new trees are planted in soil pits only about four square feet in size. Their trunks are feeble and confined to a small size (Figure 20). Some plants have barely reached full potential before getting buried in trash and snow. Nevertheless, it is reassuring to find even a few beautiful examples of nature working together with a manmade environment. This may signal that Chinatown is heading in a greener direction.

Figure 19 (left). Trees camouflage against painting on building as if they are one.Figure 20 (right). Striking contrast in size between the soil pits of the two small and two large trees

Figure 19 (left). Trees camouflage against painting on building as if they are one.Figure 20 (right). Striking contrast in size between the soil pits of the two small and two large trees

Air

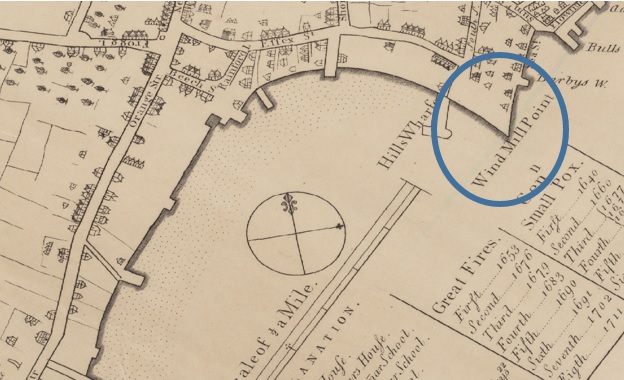

In the outskirts of Chinatown, heavy winds combined with the volume of litter in the streets pose serious environmental hazards. In one neighborhood, we find what appears at first glance to be white flower petals scattered like snow on the doorways and streets (Figure 22). Upon closer examination, we realize that the snow-like particles are melted Styrofoam. Its chemicals, along with other trash, will likely make its way to the drains either by wind or by water when it rains. To worsen the problem, a 1722 map (Figure 21) shows a “Wind Mill Point” close to Chinatown, which may suggest that Chinatown has high wind speeds. That means even more scattering of trash in Chinatown’s neighborhoods.

Figure 21. Wind Mill Point, as shown on this 1722 map (same map as Figure 1) [14]

Figure 21. Wind Mill Point, as shown on this 1722 map (same map as Figure 1) [14]

Figure 22. Melted Styrofoam scattered on the doorsteps of homes.

Figure 22. Melted Styrofoam scattered on the doorsteps of homes.

This time, there is little reprieve even in town center, where air pollutants thrive. Branching from Beach Street are narrow alleys surrounded by the tall buildings. In the distance, we see chimneys emitting smoke that, with slight aid of a wind gust, could enter the alley. The wind and the pollutants it carries could then get trapped in the alley ways, in a phenomenon outlined in The Granite Garden. Spirn describes, wind “swirls [pollutants] in the air, and the stagnant air in midblock permits them to collect.” Gusts “[swoop] down from rooftops, bring smoke from chimneys to ground level and stir up dust from street and sidewalk” [5]. The poison is then inhaled by the residents on the streets and drawn into buildings through open windows and doors.

Figure 23. Wind blowing west into this alley can be swept into this circular pattern, which traps pollutants, such as the labeled smoke, in the alley [14].

Figure 23. Wind blowing west into this alley can be swept into this circular pattern, which traps pollutants, such as the labeled smoke, in the alley [14].

The alley in Figure 23 likely suffers from this phenomena or a similar one. On a windy winter day, it was significantly less windy than the streets intersecting it, since it faced North-South and the wind was blowing East-West. Accordingly, Spirn points out that streets perpendicular to wind direction receive “little or no effective ventilation” [6]. In the alley; I felt light wind blowing around me in three different directions within a matter of seconds, which are signs that gusts and the pollutants they carry may be moving circularly, since circular trajectories involve a constant change in direction. The wind gusts may also be temporarily trapped between buildings and trying to edge their way out. Air quality in Chinatown’s alleys may be beyond healthy limits.

Effects expand beyond the obvious inhaling of pollutants. Spirn points out that “toxic dust and soot from the city air settle on soil…old building sites transformed into playgrounds or urban gardens may contain toxic soils” [7]. From Tai Tung Village, with the prospering plants we saw earlier, to Chinatown Park in city center, to the neighborhoods surround Chinatown, could all have toxins in their soil due to air pollution in Chinatown. Contaminated soils means plants that thrive today could be in trouble in the coming years. Vegetables in gardens could make residents sick. When it rains or snows, toxic water may enter the drains and flow into the Boston Harbor and Charles River. Seemingly minor pollution in a small town could infect the entire city.

Looking Forward

Today, cities’ residents are increasingly recognizing their natural environment and responding. Philadelphia, for example, as Spirn discussed in class, is taking action to prevent water damage from the Delaware River by building new drains that will keep water from reaching buildings. Spirn also pointed out in class that New York, which also suffers from the urban heat island, has small parks like Paley Park on East 53rd Street in Midtown for temporary heat relief. In Boston, the Rose F. Kennedy Greenway Conservancy builds organic parks to ensure healthy soil [8]. Philadelphia, New York, and the rest of Boston are eroded by similar natural processes as Boston’s Chinatown. There is hope that the recent drive towards green initiatives will encourage Chinatown to also improve its own urban environment.

There is already some action in Chinatown. The Rose Kennedy Greenway initiative in 2007 built Chinatown Park [9], which features more trees and bamboo to add green space to the heavily paved town. Plants thrive in and adorn Tai Tung Park. Drains and sloping sidewalks direct water away from building foundations in town center. Signs on sidewalks dissuade residents from dumping trash and chemicals into drains.

Yet Chinatown’s outskirts is still a prime example of how a small portion of a city left behind can cause widespread environmental repercussions. There, drains are heavily clogged, and trash is abundant. Thus, soil and water contamination are potential health risks. Potholes plague residential streets, buildings are cracking, and sidewalks are falling apart. Construction is developing next to the residential neighborhoods, worsening the air quality, reducing green space, and worsening the urban heat island phenomenon. Pollutants from the outskirts spread through water and air into town center and surrounding neighborhoods. To avoid further damage to itself and to its neighbors, Chinatown will need to direct more attention to the natural processes in its outskirts. It must follow in the path of other parts of Boston and other cities that have responded to similar pollution and foundation concerns due to similar natural environments. It has taken a few first steps, but it has miles left to climb.

Footnotes:

1. Spirn, Anne Whiston. The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design (New York: Basic Books, 1984), 19.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid., 136.

4. Ibid., 54.

5. Ibid., 57-58.

6. Ibid., 57.

7. Ibid., 102-104.

8. Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway Conservancy. "Chinatown Park." Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway. http://www.rosekennedygreenway.org/parks/chinatown/ (accessed March 6, 2014).

9. Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway Conservancy. "Chinatown Park." Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway. http://www.rosekennedygreenway.org/parks/chinatown/ (accessed March 6, 2014).

10. Harvard College Library. "Boston, Massachusetts, 1725 (Raster Image)." Harvard Map Collection, Harvard College Library. http://hgl.harvard.edu:8080/HGL/jsp/HGL.jsp?action=VColl&VCollName=MATWN_3764_B6_1725_B6_1835 (accessed March 6, 2014).

11. Smith, George Girdler. "Boston, Massachusetts, 1835 (Raster Image)." Harvard Map Collection, Harvard College. http://hgl.harvard.edu:8080/HGL/jsp/HGL.jsp?action=VColl&VCollName=MATWN_3764_B6_1835_S6_C1 (accessed March 6, 2014).

12. Boston, MA. (6 Mar. 2014). Google Maps, Sanborn, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA, USDA Farm Service Agemcy. Google. Retrieved from https://www.google.com/mapmaker?ll=42.350593,-71.060198&spn=0.005623,0.009398&t=h&z=18&vpsrc=6&q=Chinatown,+Boston,+MA&hl=en&utm_medium=website&utm_campaign=relatedproducts_maps&utm_source=mapseditbutton_normal

13. Harvard College Library. "Boston, Massachusetts, 1725 (Raster Image)." Harvard Map Collection, Harvard College Library. http://hgl.harvard.edu:8080/HGL/jsp/HGL.jsp?action=VColl&VCollName=MATWN_3764_B6_1725_B6_1835 (accessed March 6, 2014).

14. Spirn, Anne Whiston. The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design (New York: Basic Books, 1984), 57.

Bibliography:

Boston, MA. (6 Mar. 2014). Google Maps, Sanborn, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA, USDA Farm Service Agemcy. Google. Retrieved from https://www.google.com/mapmaker?ll=42.350593,-71.060198&spn=0.005623,0.009398&t=h&z=18&vpsrc=6&q=Chinatown,+Boston,+MA&hl=en&utm_medium=website&utm_campaign=relatedproducts_maps&utm_source=mapseditbutton_normal

Harvard College Library. "Boston, Massachusetts, 1725 (Raster Image)." Harvard Map Collection, Harvard College Library. http://hgl.harvard.edu:8080/HGL/jsp/HGL.jsp?action=VColl&VCollName=MATWN_3764_B6_1725_B6_1835 (accessed March 6, 2014).

Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway Conservancy. "Chinatown Park." Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway. http://www.rosekennedygreenway.org/parks/chinatown/ (accessed March 6, 2014).

Smith, George Girdler. "Boston, Massachusetts, 1835 (Raster Image)." Harvard Map Collection, Harvard College. http://hgl.harvard.edu:8080/HGL/jsp/HGL.jsp?action=VColl&VCollName=MATWN_3764_B6_1835_S6_C1 (accessed March 6, 2014).

Spirn, Anne Whiston. The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design. New York: Basic Books, 1984.