Hidden in artifacts, traces, and layers of historical periods are stories of individual residents, whole communities, and even national systems such as former methods of transportation or trade. On my site today, artifacts and traces represent four larger systems from the past: the railroad-centered community of the mid-19th century, the Chinese garment industry of the late 19th century, the rise of the Chinese-American community in the early 20th century, and the urban renewal of the mid-20th century. Much of what remains seems to be preserved due to their location in the commercial center of Chinatown, their inherent condition and the condition of their surroundings, or their historical significance. If these trends continue, while parts of the border of my site may be at risk for redevelopment in the near future, it seems that the majority of my site will likely be preserved for many more years to come.

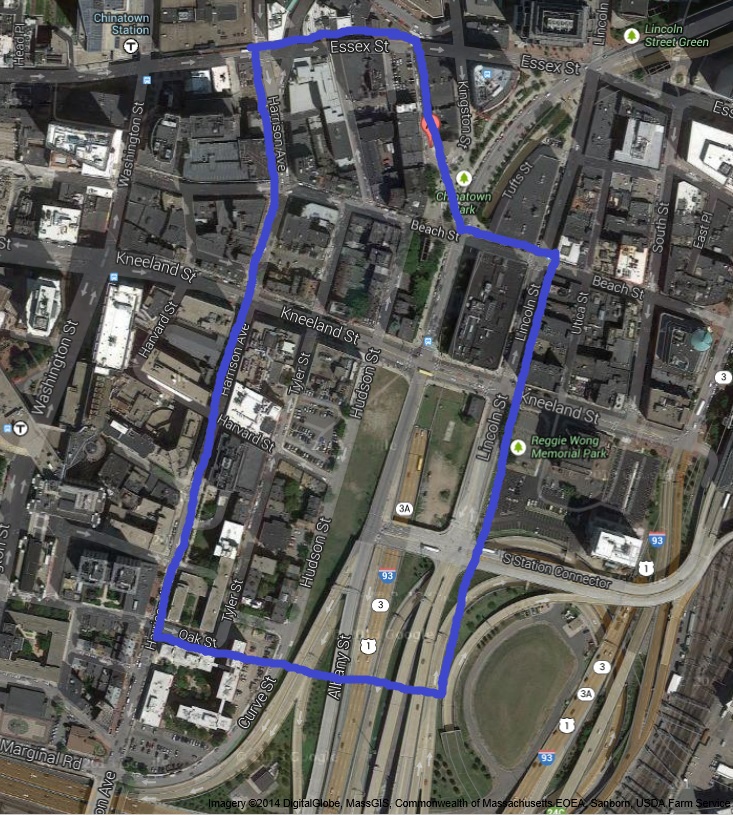

Google Maps Satellite View of Chinatown, as accessed in April 2014 [1]. Site today.

Google Maps Satellite View of Chinatown, as accessed in April 2014 [1]. Site today.

Artifacts and Traces of the Mid-19th Century: Railroad-Centered Community

In the mid-19th century, the lanes of Interstate 93 on my site were once railroad tracks of the Boston and Albany Railroad. Along with the few surviving 19th century buildings, I-93 is a trace of the former railroad community (Figure 1). In The Power of Place by Dolores Hayden, Hayden writes, “One can understand the railroad in engineering terms…without fully capturing its social history as the production of space…[T]wenty-nine Chinese workers died while building Wrights Tunnel for the South Pacific Coast Railroad…in 1879” [2]. Even though the railroad workers of my site were likely European (since the railroad was built before the Chinese arrived, as discussed in my previous paper), unlike the workers that Hayden described, railroad communities across the nation share many of the same living conditions and lifestyles. Chinatown’s mid-19th century residents must have lived under the same smoke and soot from the railroad, endured the noise pollution of passing trains, labored in the harsh conditions of railroad construction, and perhaps lost loved ones in railroad accidents, as Hayden suggested. I-93 on my site brings back memories of the difficult lives of many residents of former railroad communities around the U.S. in the 19th century.

Figure 1. The expressway marks much of the former location of the Boston and Albany Railroad.

Figure 1. The expressway marks much of the former location of the Boston and Albany Railroad.

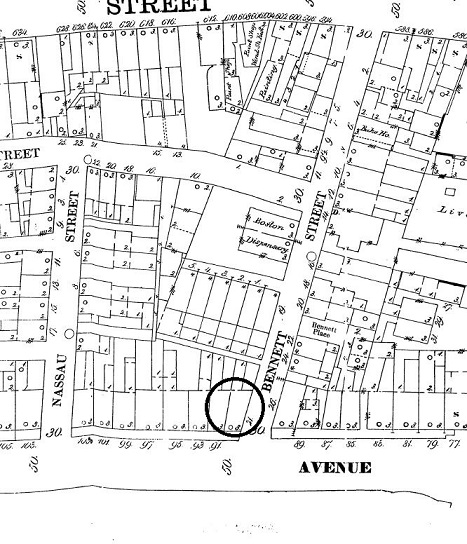

Even though the railroad no longer exists, a few artifacts - a multi-story dwelling and the Quincy School - from the period have been preserved, likely due to the buildings’ conditions and historical significance. They give clues to the income levels of some of the neighborhood’s early residents. The former multi-story dwelling is one of Tufts Medical Center’s buildings on Bennet Street today (Figures 2 and 3). It has existed at least since 1867 (Figure 4). Although it is unmarked on the map, it was likely a dwelling since the commercial and industrial properties are marked. From the size of the building, it seems that the owner may have been wealthy. Moreover, before my site was filled, it used to border the bay, so it makes sense that a wealthy owner would want a view of the bay from his home. This suggests that although my site quickly became a working class neighborhood, there may have been wealthy settlers on my site before railroad construction began. Today, it is one of Tufts Medical Center’s buildings.

The adaptation of the multi-story dwelling to different uses through the past 200 years is evidenced by its incongruous layers of architecture, from the original brick building, to a stone arch added at its doorway to a bay-window-like addition on its upper levels (Figure 2). The red brick seems to be first layer, since it makes up most of the building and is also the same material used to build the 19th century dwellings. The addition of white brick and stone probably came later, and the blue bay window was probably the most modern addition. The building likely still survives today due to its size and better quality compared to the small workers’ homes in the rest of my site. Tufts was willing to take over this building in its existing state.

Figure 2 (left). Front view of a Tufts Medical Center building showing layers from different periods. Figure 3 (right). Side view of a Tufts Medical Center building showing layers from different periods.

Figure 2 (left). Front view of a Tufts Medical Center building showing layers from different periods. Figure 3 (right). Side view of a Tufts Medical Center building showing layers from different periods.

Figure 4. Sanborn Map of 1867. The building is circled in black. Although it was smaller in 1867, it was already a multi-story building [3]. The Boston Dispensary is just a few buildings away.

Figure 4. Sanborn Map of 1867. The building is circled in black. Although it was smaller in 1867, it was already a multi-story building [3]. The Boston Dispensary is just a few buildings away.

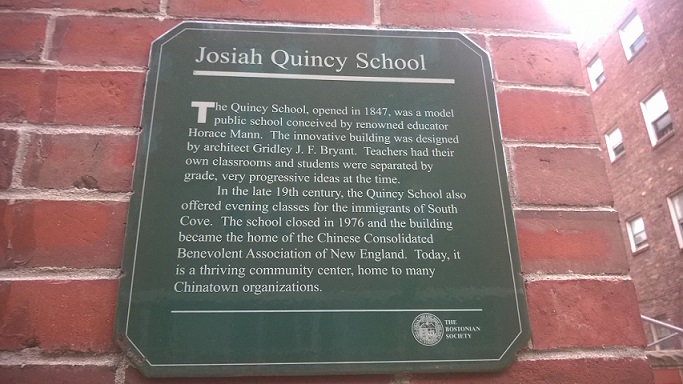

The Quincy School, which has been on my site since 1847, may also have been preserved due to its better quality, but more importantly for its historical significance (Figures 5 and 6). The sign in Figure 3 on the building states that the former Quincy School was public school that even “offered evening classes for the immigrants of South Cove” (Figure 5). Today it still serves a somewhat educational purpose as a community center for Chinatown’s residents. The preservation of the building as a site for community gatherings, and the informational sign itself on the building suggests that there was probably push in the community and in Boston to preserve the school.

Figure 5. Plaque on the Quincy School today.

Figure 5. Plaque on the Quincy School today.

Figure 6. Quincy School today. It is now a Chinese community center.

Figure 6. Quincy School today. It is now a Chinese community center.

Artifacts of the Late 19th to Early 20th Centuries: Garment Industry

Figure 5b. Sanborn Map of 1885 [12]. Early Chinese settlers started a garment industry, as evidenced by the Chinese laundries labeled on the map.

Figure 5b. Sanborn Map of 1885 [12]. Early Chinese settlers started a garment industry, as evidenced by the Chinese laundries labeled on the map.

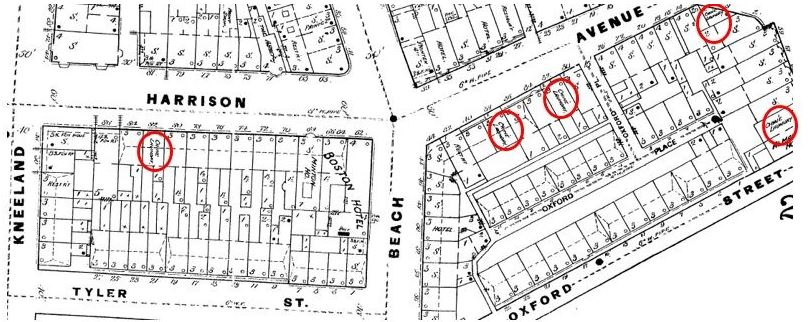

From the late 19th to early 20th century, Chinese immigrants began to arrive and start a garment industry (Figure 5b). A few of the industrial buildings still survive today likely because of their location further away from the rim of Chinatown. The buildings in Figure 4 (Oxford Street) were industrial buildings during this period (Figure 6). They are mostly commercial today, with the exception of the Ho Toy Noodle Factory, which occupies a portion of one of the buildings (Figure 7). The buildings still look industrial in nature, even adorned by the occasional smoke in the background, as shown in Figure 4. They leave a reminder of the lives of the Chinese and other blue collar workers, who labored and endured the pollution, sweat, filth, and other adverse conditions of early industrial factories.

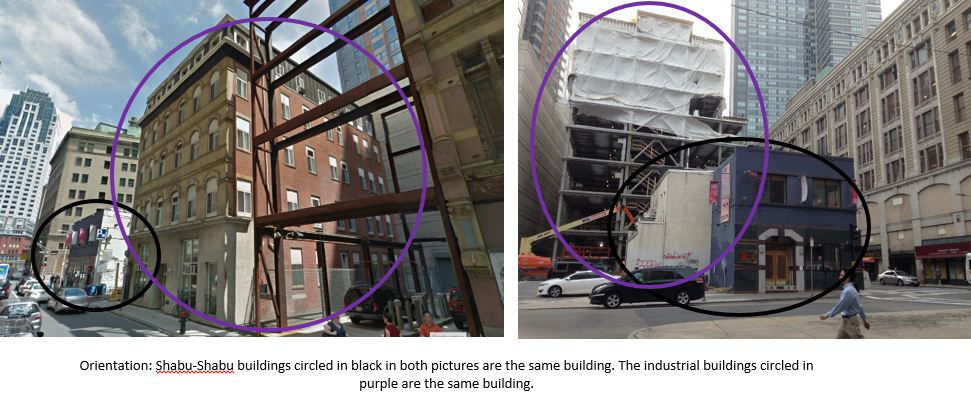

Yet, some of the industrial buildings close to the outer border of my site have not survived. In Figure 5, the Google Maps 2014 image shows an industrial building still standing. However, today, in April 2014, the building is in the process of being rebuilt (Figure 8). The lonely Chinese Shabu Shabu building in front seems to sit precariously, bound to be destroyed at any time. The industrial buildings on Oxford Street may still be preserved because they are closer to the heart of Chinatown and are located next to old, barely maintained, tenement buildings, while the industrial buildings in Figure 7 are closer to new establishments outside Chinatown. Prospective landowners may not find it worthwhile to develop buildings near former tenement buildings when more attractive spaces, surrounded by clean and modern buildings, are available.

Figure 6. Sanborn Map of 1929. The buildings lining Oxford Street are industrial (circled in, and colored, purple) [4]. The elevated railroad (discussed later) is circled in black.

Figure 6. Sanborn Map of 1929. The buildings lining Oxford Street are industrial (circled in, and colored, purple) [4]. The elevated railroad (discussed later) is circled in black.

Figure 7. Former industrial buildings on Oxford Street today. Today most of the building use is commercial, with the exception of the back right building, which houses a noodle factory.

Figure 7. Former industrial buildings on Oxford Street today. Today most of the building use is commercial, with the exception of the back right building, which houses a noodle factory.

Figure 8. Left Image from Google Maps [5]. The industrial building shown to the left still existed when Google Maps uploaded this image, but today it is being taken down and rebuilt, as shown in the image to the right. Meanwhile, juxtaposed with the industrial buildings is the small blue-colored shop in front of it. It is a Shabu Shabu place that seems at risk for destruction at any time.

Figure 8. Left Image from Google Maps [5]. The industrial building shown to the left still existed when Google Maps uploaded this image, but today it is being taken down and rebuilt, as shown in the image to the right. Meanwhile, juxtaposed with the industrial buildings is the small blue-colored shop in front of it. It is a Shabu Shabu place that seems at risk for destruction at any time.

Many of the 19th century dwellings and tenement buildings that the industrial workers lived in still exist today, carrying with them the stories and living conditions of early Chinese residents. However, a significant portion has also been destroyed to make way for Tufts Medical Center. The ones that are still standing today may have survived due to differences in building conditions and locations, and also because of the recent push in the Chinese community to preserve their community. Examples of tenements and dwellings of the 19th and early 20th centuries are the ones on Hudson and Harvard Streets, and Oxford Place (Figures 9 and 10). Hayden writes that urban building types, like tenements, “represent the conditions of thousands or millions of people” [6]. She writes that “[t]he claustrophobic experiences of immigrants living for decades in crowded, unhealthy space…are conveyed by the building in a way that a text or a chart can never match” [7]. Such conditions can still be found in the tenements that survive today. Figure 10b depicts tenements on Oxford Place, located in dark, claustrophobically narrow alleys, where dirt and trash collect and build over time. Tall industrial buildings in neighboring blocks often block sunlight from reaching the tenements. Space between tenements are so small that one could hear any substantial noise even from other tenements. The tenements surviving in my site today reveal the harsh living conditions of the Chinese immigrants, and also immigrants from many different countries living in the U.S. at the time.

Figure 10b. Tenements on Oxford Place in claustrophobically narrow and dark alleys. The tenement buildings are barely a few feet apart from each other. Residents lack privacy, and dirt and trash build up over time around the buildings. An original lamp from the 19th century still stands, suggesting that the tenements have not been renovated since the 19th century.

Figure 10b. Tenements on Oxford Place in claustrophobically narrow and dark alleys. The tenement buildings are barely a few feet apart from each other. Residents lack privacy, and dirt and trash build up over time around the buildings. An original lamp from the 19th century still stands, suggesting that the tenements have not been renovated since the 19th century.

Figure 11. Trace of a former 19th century dwelling that was cleared to build a parking lot (shown in the map below (Figure 11b)).

Figure 11. Trace of a former 19th century dwelling that was cleared to build a parking lot (shown in the map below (Figure 11b)).

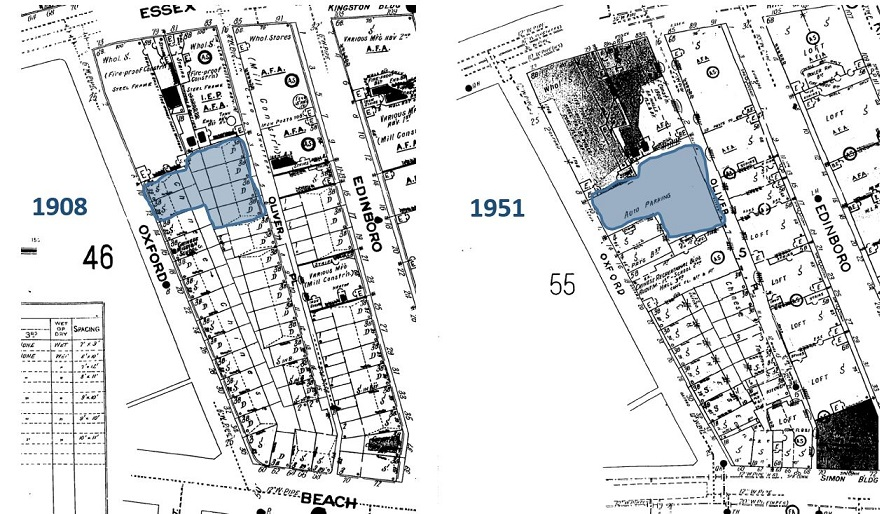

Figure 11b. Sanborn Maps of 1908 and 1951 [13] and [14]. A series of dwellings was cleared after 1908 to build a parking lot close to a Chinese recerational building. A trace of the removed buildings is shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11b. Sanborn Maps of 1908 and 1951 [13] and [14]. A series of dwellings was cleared after 1908 to build a parking lot close to a Chinese recerational building. A trace of the removed buildings is shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11c. Trace of a former 19th century dwelling that was cleared to buikld a parking lot next to a large commercial building (shown in map below (Figure 11d)). Today the commercial building is home to the East West bank.

Figure 11c. Trace of a former 19th century dwelling that was cleared to buikld a parking lot next to a large commercial building (shown in map below (Figure 11d)). Today the commercial building is home to the East West bank.

Figure 11d. Sanborn Maps of 1908 and 1951 [13] and [14]. A series of dwellings was cleared after 1908 to build a parking lot close to a large commercial building. A trace of the removed buildings is shown in Figure 11c.

Figure 11d. Sanborn Maps of 1908 and 1951 [13] and [14]. A series of dwellings was cleared after 1908 to build a parking lot close to a large commercial building. A trace of the removed buildings is shown in Figure 11c.

There are likely two reasons why the pictured tenements (Figure 10b) and many other dwellings remain, while many other dwellings no longer exist (Figure 11 and 11c). First, the surviving dwellings are a poor condition and thus may not be worthwhile to redevelop. Many of the removed buildings were next to much larger buildings in a better and more useful state (Figure 11). Thus, the smaller buildings may have been destroyed because they were easier to remove and not as useful or well-maintained as their neighbors.

Second, the surviving buildings are not directly next to large commercial buildings or centers for community gatherings - places that would require that space close by be cleared for parking. As shown in the maps in Figure 11b (corresponding to the site of Figure 11), a series of dwellings was removed between 1908 and 1951 to build a parking lot. At the same time, a large Chinese recreational building sprang up between 1908 and 1951. Creating parking space next to this community building would only be practical. Similarly, the maps of Figure 11d (corresponding to the site of Figure 11c) suggest that dwellings were converted into parking spaces likely because a large commercial building sprang up next to the dwellings between 1908 and 1951. Today, that building is home to the East West Bank; it likely needs to provide parking space to attract as many customers as possible. It seems that the dwellings that have not survived were often unfortunate enough to have large commercial or community centers built next to them.

Figure 9. Tenements on Oxford Place.

Figure 9. Tenements on Oxford Place.

Figure 10. 19th Century dwellings that still remain. They are not well-maintained, which may drive away potential buyers.

Figure 10. 19th Century dwellings that still remain. They are not well-maintained, which may drive away potential buyers.

Early to Mid 20th Century: Chinese Community and the Elevated Railroad

Many buildings of Chinese architecture in the early or mid-20th century still survive today and represent the growing Chinese wealth, community, and pride in that period. These artifacts seem to be preserved because of the drive of the residents to display cultural pride in Chinatown and also because of their location in Chinatown’s commercial center. Figure 12 shows the restaurant China Pearl, which MIT Professor Tunney Lee indicated has been there since around the mid-19th century, with its sign in both English and Chinese [8]. Figure 13 also shows Chinese architecture, which may or may not have been created more recent than the mid-20th century. Nevertheless, it represents historical Chinese architectural style, a reminder of the growing pride in Chinatown during the period. Hayden writes that “[e]thnic vernacular arts traditions…instill community pride and signal the presence of a particular community in the city” [9]. Both the Chinese architecture and China Pearl represent artifacts serving as reminders of the period when the Chinese moved away from industry, survived the Great Depression, and were able to open restaurants and display their pride and culture.

Figure 12. China Pearl Restaurant.

Figure 12. China Pearl Restaurant.

Figure 13. Chinese architecture.

Figure 13. Chinese architecture.

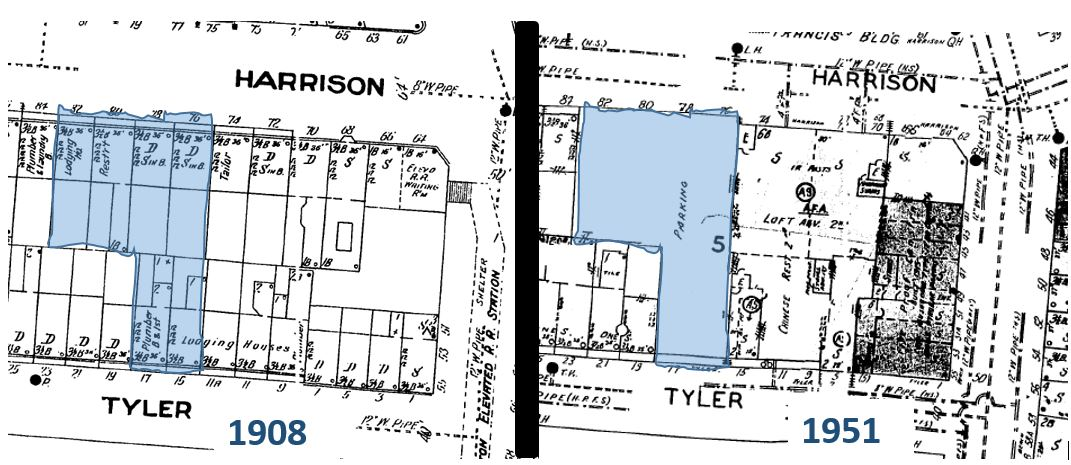

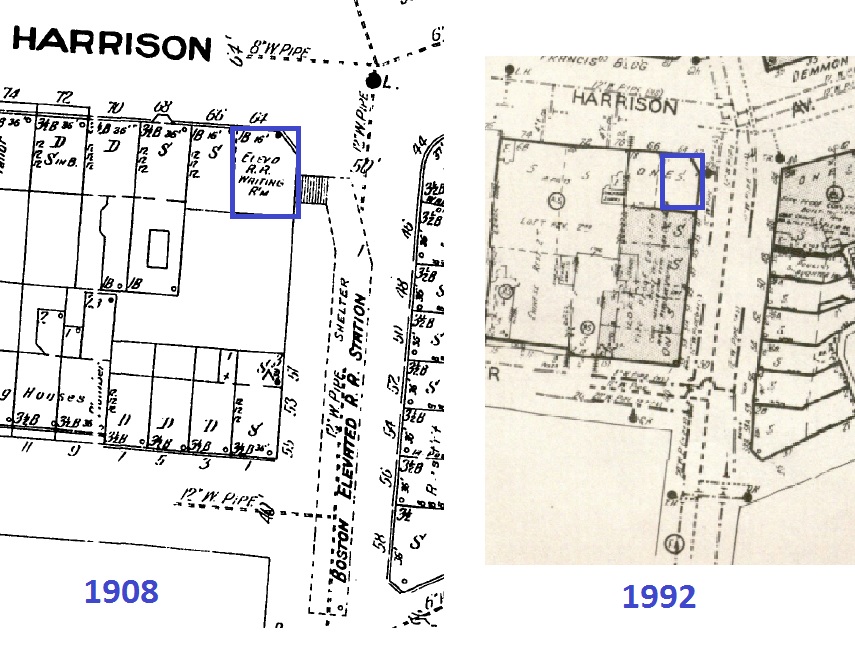

A less cheerful reminder of the early 20th century is the trace of the elevated railroad that once ran on Harrison Avenue and Beach Street, reminding residents of a former way of transportation. None of its tracks remain, but it leaves a trace at the two streets’ intersection (Figure 14). Professor Tunney Lee informed me that Maxim’s Coffee Shop is only one story high, while its neighbors are multistory, because the elevated railroad used to run above the shop, which in fact, used to be a railroad station. The railroad station, sitting where Maxim’s coffee ship is today, is also shown in the Sanborn Map in Figure 14b. Professor Lee remarked that many accidents and deaths occurred with the elevated railroad, especially when train cars ran too quickly [8]. One can also imagine the noise pollution, the smoke, and perhaps the shaking of windows and buildings as the train passed so close to the stores. According to the Sanborn Map of 1929 (Figure 6), the elevated railroad existed in 1929, around the time of the Stock Market Crash and the Great Depression. Maxim’s one-story coffee shop and the intersection of Harrison and Beach Streets represent not only the dangers of the railroad, but also the suffering of neighborhoods across the country during the harsh era of the Great Depression. The elevated railroad may have helped shops get more business during the harsh economic period, but it was at the risk of residents’ lives.

Figure 14. The elevated railroad used to run at this intersection and pass above Maxim’s Coffee Shops, which was a former railroad station. See map (Figure 14b) below for evidence of the former railroad and railroad station in the Sanborn maps.

Figure 14. The elevated railroad used to run at this intersection and pass above Maxim’s Coffee Shops, which was a former railroad station. See map (Figure 14b) below for evidence of the former railroad and railroad station in the Sanborn maps.

Figure 14b. Sanborn Maps of 1908 and 1992 [13] and [15]. The railroad station has been preserved from 1908 until today. It is now Maxim’s Coffee Shop. The location of the elevated railroad is also marked on the 1908 map.

Figure 14b. Sanborn Maps of 1908 and 1992 [13] and [15]. The railroad station has been preserved from 1908 until today. It is now Maxim’s Coffee Shop. The location of the elevated railroad is also marked on the 1908 map.

The Chinese Merchants Association building is a bittersweet artifact from this period, serving as an iconic symbol of community pride, but also ironically a victim of urban renewal and a site of prostitution. The Chinese Merchants Association still stands today (Figure 14b), with a pagoda on its roof and a sign saying, “Welcome to Chinatown.” Like China Pearl, it represents the growing pride in the cultural community. However, as discussed in the previous paper, half of the building was lost due to the expressway. This is likely due to its unfortunate location close to the rim of my site, where the expressway cut through. The Chinese Merchants Association building is an artifact reminding Chinatown’s residents of what their community has lost to government projects.

Figure 14b. Chinese Merchants Association building today. The incongruous layers of newer buildings and construction that surround the old building serve as a reminder the encroachment of institutions and government onto Chinatown.

Figure 14b. Chinese Merchants Association building today. The incongruous layers of newer buildings and construction that surround the old building serve as a reminder the encroachment of institutions and government onto Chinatown.

Urban Renewal and Trend Today

The traces of urban renewal – Tufts Medical Center and the expressway - can clearly be found on my site today, serving as a reminder of the many displaced residents in Chinatown. These new developments coexist with the historical artifacts from the previous three periods discussed in this paper, to form at least four different layers of history in the small neighborhood. The contrast between new developments and historic artifacts foreshadow a trend of redevelopment that could affect Chinatown in the near future.

Figure 15. 19th century homes surrounded by Tufts Medical Center.

Figure 15. 19th century homes surrounded by Tufts Medical Center.

Urban renewal on my site is evidenced by the expansion of Tufts Medical Center and the creation of parking lots in Chinatown. In Figure 15, the new buildings on the left and right are Tufts Medical Center facilities, while sandwiched in the middle are old 19th century dwellings that were not removed by Tufts. According to Hayden, urban renewal could have triggered many to “[mourn] for a lost neighborhood” due to an attachment theory that “explain[s] the power of human connections to places that may no longer exist physically” [10]. This incongruous block of old and new buildings is an artifact of the displacement of many families from their homes across the U.S. during urban renewal, and the resulting emotions of sadness and loss.

Will the trend set by urban renewal, where institutions and government increasingly encroach on Chinatown’s properties, continue? It is impossible to know for sure, but one way to extrapolate would be to examine previous trends of what is destroyed and what is preserved. Since the early 19th century, many buildings that have been spared by redevelopers are in an undesirable condition. Other surviving buildings are far from large commercial buildings, have historical significance, or are away from the rim of my site. According to the first factor, and also as Professor Tunney Lee remarked, it seems that as long as the Chinese still live in the homes, many of which are not well-maintained, Chinatown’s land will likely not be claimed [8].

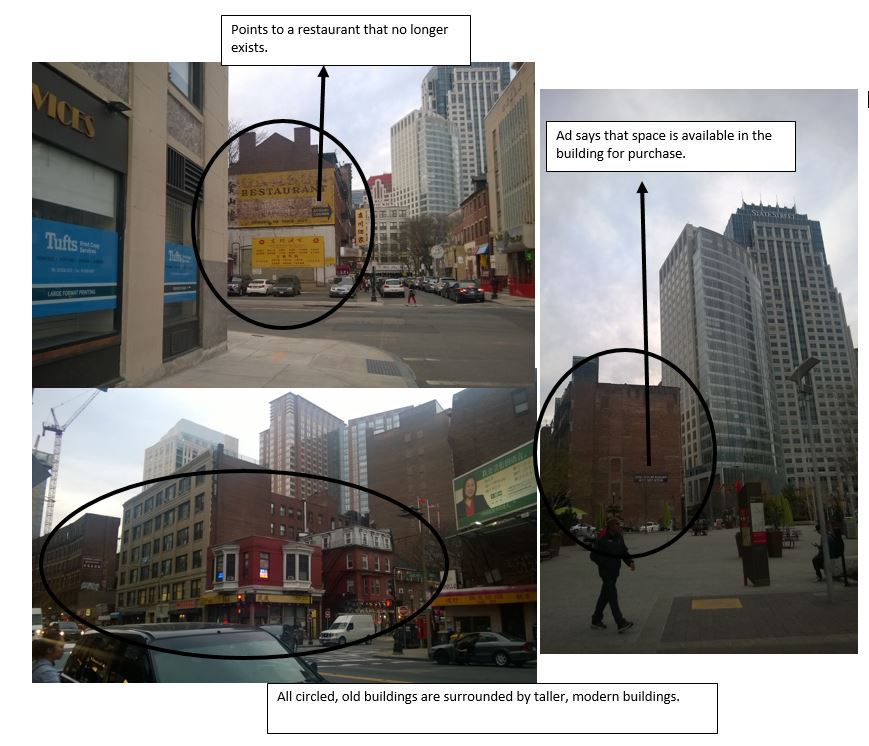

The other factors, however, could suggest that Chinatown is at some risk for losing more properties, especially at the rim of my site, evidenced by the many nonconforming layers of different time periods seen on the site today, and ongoing construction at my site’s border. As shown in Figure 8, some of Chinatown’s stores at the rim of the site are at risk for destruction and redevelopment. There is also ongoing construction of new housing that may not be affordable to the Chinese residents (Figure 16). Finally, as evidence by Figure 17, Chinatown is largely shadowed by new, tall, commercial buildings such as State Street Corporation’s building. As more expensive buildings spring up around Chinatown’s borders, my site, especially the rim of my site, may be increasingly at risk of being redeveloped.

Figure 16. Construction of new homes that the government claims is “affordable,” but it is unknown how affordable these homes really are to Chinatown’s residents.

Figure 16. Construction of new homes that the government claims is “affordable,” but it is unknown how affordable these homes really are to Chinatown’s residents.

Figure 17. Chinatown’s old buildings, such as the circled buildings, are largely shadowed by new, tall, buildings such as State Street Corporation’s building, as shown in the pictures. As more expensive buildings spring up around Chinatown’s borders, my site, especially the rim of my site, may be increasingly at risk of being redeveloped.

Figure 17. Chinatown’s old buildings, such as the circled buildings, are largely shadowed by new, tall, buildings such as State Street Corporation’s building, as shown in the pictures. As more expensive buildings spring up around Chinatown’s borders, my site, especially the rim of my site, may be increasingly at risk of being redeveloped.

Still, the third factor of historical significance may save Chinatown from further loss. As discussed in the previous section, Chinatown’s residents are increasingly pushing for affordable housing so that its residents can remain in Chinatown. They show an increasing sense of pride and willingness to voice their opinions. Moreover, Chinatown’s significance as a cultural community since the 19th century may spare it from redevelopment. After all, as Hayden suggests, “[P]lace attachment can develop social, material, and ideological dimensions, as individuals develop ties to kin and community” [11]. From the preservation of Quincy School to the many shops that still exist in Chinatown today, there seems to be a drive to preserve history and culture both internally and from the greater Boston community.

Footnotes:

1. Boston, MA. (1 Apr. 2014). Google Maps, Sanborn, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA, USDA Farm Service Agemcy. Google. Retrieved from https://www.google.com/mapmaker?ll=42.350593,-71.060198&spn=0.005623,0.009398&t=h&z=18&vpsrc=6&q=Chinatown,+Boston,+MA&hl=en&utm_medium=website&utm_campaign=relatedproducts_maps&utm_source=mapseditbutton_normal

2. Hayden, Dolores. The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History. (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1995), 21.

3. Boston, Massachusetts [map]. 1867. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1867". Digital Sanborn Maps 1867. < http://sanborn.umi.com.libproxy.mit.edu/ma/3693/dateid-000035.htm?CCSI=254n> (1 Apr 2014).

4. Boston, Massachusetts [map]. 1929. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1929". Digital Sanborn Maps 1929. < http://sanborn.umi.com.libproxy.mit.edu/ma/3693/dateid-000035.htm?CCSI=254n> (1 Apr 2014).

5. Boston, MA. (1 Apr. 2014). Google Maps, Sanborn, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA, USDA Farm Service Agemcy. Google. Retrieved from https://www.google.com/mapmaker?ll=42.350593,-71.060198&spn=0.005623,0.009398&t=h&z=18&vpsrc=6&q=Chinatown,+Boston,+MA&hl=en&utm_medium=website&utm_campaign=relatedproducts_maps&utm_source=mapseditbutton_normal

6. Hayden, Dolores. The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History. (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1995), 33.

7. Ibid.

8. Lee, Tunney. Interview by author. Cambridge, April 10, 2014

9. Hayden, Dolores. The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History. (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1995), 38.

10. Ibid, 29.

11. Ibid, 16.

12. Boston, Massachusetts [map]. 1885. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1885". Digital Sanborn Maps 1885. < http://sanborn.umi.com.libproxy.mit.edu/ma/3693/dateid-000035.htm?CCSI=254n> (1 Apr 2014).

13. Boston, Massachusetts [map]. 1908. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1908". Digital Sanborn Maps 1908. < http://sanborn.umi.com.libproxy.mit.edu/ma/3693/dateid-000035.htm?CCSI=254n> (1 Apr 2014).

14. Boston, Massachusetts [map]. 1951. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1951". Digital Sanborn Maps 1951. < http://sanborn.umi.com.libproxy.mit.edu/ma/3693/dateid-000035.htm?CCSI=254n> (1 Apr 2014).

15. Boston, Massachusetts [map]. 1992. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1992". Digital Sanborn Maps 1992. < http://sanborn.umi.com.libproxy.mit.edu/ma/3693/dateid-000035.htm?CCSI=254n> (1 Apr 2014).

Bibliography:

Boston, MA. (1 Apr. 2014). Google Maps, Sanborn, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA, USDA Farm Service Agemcy. Google. Retrieved from https://www.google.com/mapmaker?ll=42.350593,-71.060198&spn=0.005623,0.009398&t=h&z=18&vpsrc=6&q=Chinatown,+Boston,+MA&hl=en&utm_medium=website&utm_campaign=relatedproducts_maps&utm_source=mapseditbutton_normal

"Chinatown residents press Walsh on affordable housing - The Boston Globe." BostonGlobe.com. http://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2014/02/05/chinatown-residents-press-walsh-affordable-housing/0ZKEhdJ68Id7SlGmffjVpM/story.html (accessed April 18, 2014).

J"Cityofboston.gov - Official Web Site of the City of Boston." Subsidized Housing. http://www.cityofboston.gov/dnd/brhc/housing.asp (accessed April 18, 2014).

Hayden, Dolores. The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1995. Print.

Lee, Tunney. Interview by author. Cambridge, April 10, 2014.

Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps.” Digital Sanborn Maps. < http://sanborn.umi.com.libproxy.mit.edu/ma/3693/dateid-000002.htm?CCSI=254n> (1 Apr 2014).