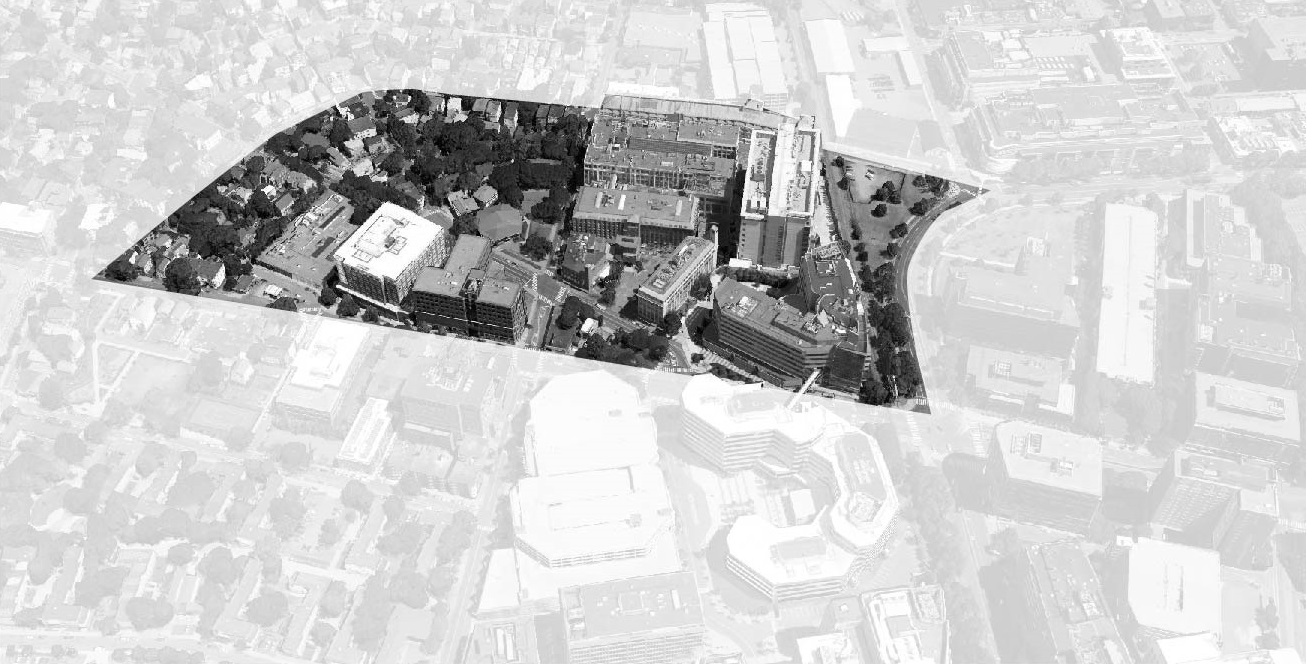

Source: “Bird’s Eye of Site.” 42deg21’58.77” N 71deg05’30.38”W. Google Earth. August 24, 2013. March 6, 2015

Source: “Bird’s Eye of Site.” 42deg21’58.77” N 71deg05’30.38”W. Google Earth. August 24, 2013. March 6, 2015

Cities are always evolving to suit the needs of their inhabitants. From its inception to the present day, my site has been fundamentally altered by the generations of people that have established a place for themselves. Specifically, the site has undergone a variety of changes relating to infrastructure, land usage, and economy. While these important historical precedents played a role in informing the current reading of the site, the physical experience of the site shows a trend in community growth through repurposing of the industrial sector, and preservation of original residential buildings.

One of the major themes of my site is one of repurposing original industrial sites for the sake of creating a community oriented space. The main example of this takes shape from the redevelopment of the former Boston Rubber Company (bounded by Hampshire Street, Portland Street, and the railroad). Currently known as Kendall Plaza, this space is surrounded by the building footprint of the old factory. From their brick façade, large windows with wooden frames, it would seem that the current buildings are the ones that existed in 1900. The meaning of this artifact is supported by the trace of the basement windows that have been covered in order to create a basement space for the building (see pictures 1 + 2 below).

Picture 1 - ARTIFACT - The buildings surrounding Kendall Plaza most likely contain the original building materials, due to the presence of brick and wooden window frames. All photos were taken by author unless otherwise noted.

Picture 2 - TRACE - The presence of brick under the windowsill indicates the covering of a former window to create a basement space for the restaurant venues in Kendall Plaza.

The presence of the façade certainly indicates the longevity of the industrial building form as well as the desire of the community to maintain the building for a couple of potential reasons. The first is that the location of the buildings and the plaza at the intersection of Hampshire and Broadway grants this space accessibility for vehicles and pedestrians, creating a central environment around which the community can gather. The second reason can be attributed to maintaining historical artifacts reminiscent of the industrial age that set such an important precedent for the site. The materials of brick and wood also lend themselves to a warm, welcoming space. What differs from the original plans of the site, however, is the presence of a bricked plaza in the space left from the buildings. The plaza seems to be the space left by the surrounding buildings, and the brick appears to be added recently as a way to strengthen the concept of a central, “courtyard” gathering space.

In terms of layers, Kendall Plaza shows the progression of industry through time. The brick buildings contain two layers in themselves: the wood window frames and green panelized roof reminiscent of early 20th century industry, and the bricked up windows and signs for Irish pubs of the current day. Juxtaposed with its neighbors, the renovated buildings of the Schlumberger Institute and the Amgen building show the increasingly efficient construction materials for increasingly efficient technological practices (see pictures 3 + 4 below).

Picture 3 - LAYER - The building juxtaposed tot he original factory maintains the large windows and green panelized roof, potentially to add continuity between the buildings. Here, the layer of the original building and its successor can be compared.

Picture 4 - LAYER - Here is the original building and another laboratory building. Unlike in picture 3, the building on the left has no aesthetic similarities to the original.

These artifacts indicate that there could be at least three layers in the industrial sector. First is the original brick industrial building. The second artifact is the office building bounding the eastern side of the plaza that has a roof similar to the original, although the façade is clad with glass and concrete (picture 3). Following is the presence of bricked up windows, restaurant signs, and expansion and renovation of the Amgen and Schlumberger buildings (picture 4). While the composition of these facades is interesting, perhaps they stand for more than aesthetic. The juxtaposition of building technologies seems to quantify the progression that the site has made in terms of industry: moving from rubber manufacturing to processing synthetic oil and gasoline. Ultimately, the maintenance of the original industrial complex and the surrounding development could make the community more oriented towards progress. As Dolores Hayden notes of cases like East Harlem in 'The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History,' “The organizers [of the casitas project] have produced their own public space, setting up a series of oppositions – past/present, inviting/uninviting, private/public” (Hayden, 35-6). As seen in Kendall Plaza, the presence of old architecture combined with modern functionality serves to create a welcoming public area for city inhabitants and reinforce their respect for historical landmarks.

Given these examples, there seems to be a trend of reassigning industrial land use for more community-oriented spaces. This suggests a shifting desire to place a more socially aware environment in the same regard as technologic or economic advancement.

In addition to development of community space through repurposing, the preservation of historical artifacts and events indicates local interests. Hayden states that “a new kind of urban preservation is emerging in the 1990s in community based public history, architectural preservation focusing on vernacular buildings, landscape preservation, and commemorative public art” (228). We will see that the preservation of architectural precedents and public consideration of historic social events play a major role in the site.

While the preservation of artifacts can be seen in Kendall Plaza, more prominent examples come from the tenement housing and duplex homes. Tracing the building footprints through almost a century of Sanborn maps shows that a sizeable amount of the original site has been maintained (fig. 1).

Fig. 1 - ARTIFACT - The building footprints outlined in red are ones that exist today, originating in 1900. The figure is a collage of the current facades of such buildings, showing the maintenance of such styles.

When making observations on the site, the building façades seem to be quite similar to the original. The clearest example of this is the duplex house on the corner of Bristol and Hampshire (pictured below).

The federal style of this building indicates it is part of the original urban landscape.

This artifact is an example of an early federal style – the single surfaced façade and little ornamentation mark this house as a part of the original neighborhood scheme. We know it is maintained because there have been skylights installed, as well as clean, groomed shrubbery outside. Further examples of a desire to maintain old styles are found in individual homes and apartments. The houses pictured below have maintained a form similar to that of an earlier time. However, they have been given fresh coats of paint, as well as small ornamentation details.

These artifacts show the desire to maintain original building structures, and indicate a sense of community pride in the historical nature of the building façades. In addition to simple preservation of the façade and form of the building, the ornamental additions suggest additional historical thought was brought into the building. The major representation of this language comes in the form of porticos (fig. 2). From this addition, it is clearer to see the layers of original building placement and form, reconstruction of façade, and finally, the detail work of the ornament.

Fig. 2 - ARTIFACT - This diagram shows the three major typologies of portico design in the residential area of my site. The leftmost is a smaller scale, but richly detailed extrusion. It tended to be found on tenement houses. The middle one represents a support that was richly decorated and larger in scale. This kind of portico was found in duplex homes. Lastly, the rightmost ornament is of simple form, and constructed of wrought iron. It was a rare and varied type of ornament; it was found on a single-family house as well as an apartment building.

The ornamentation details such as porticos, decorative shutters, and paint bring the buildings into a more contemporary setting. It would seem that the people who inhabit these houses are proud to take care of them, but are also defining their own style through embellishment.

The second example of community building through historical preservation comes from the recognition of social diversity on the site.

As seen previously from the Sanborn maps, the Italian Cultural center appeared in the middle of the site in 1973. This obviously indicates a strong presence of Italian heritage in and around the site, but also indicates the willingness of the community to create such a culturally supportive space. Hayden notes “Large urban ethnic groups evidently built little that was distinctive but instead expressed their ethnicity through language, food customs, religious and social organizations” (34). While the Italian Cultural Center may be a bit of an anomaly in this sense, it remains an artifact of the increasing amount of Italian immigrants in the site. The distinctive geometry and material of the artifact make it especially distinctive; for the orange tiles and octagonal plan are rarely found in the traditional Cambridge buildings (see right). However, for the Italian community, it may serve as a beacon of traditionally Italian building methods.

Immigrants are also honored with the renaming of Portland street north of Hampshire Street to Cardinal Medeiros Avenue. The Cardinal Humberto Sousa Medeiros was an archbishop of Boston in 1970. A Portuguese immigrant himself, Cardinal Medeiros founded the building that housed the St. Anthony’s Parish, a church dedicated to religious services for poor Portuguese immigrants. Not only was the street named in his honor, but also a homeless shelter and a college scholarship . The Sanborn 1996 map doesn’t show this conversion to Cardinal Medeiros Avenue. This indicates that the artifact of the street is locally named, in order to preserve the memory of the Portuguese immigrant who helped to make the community a better place.

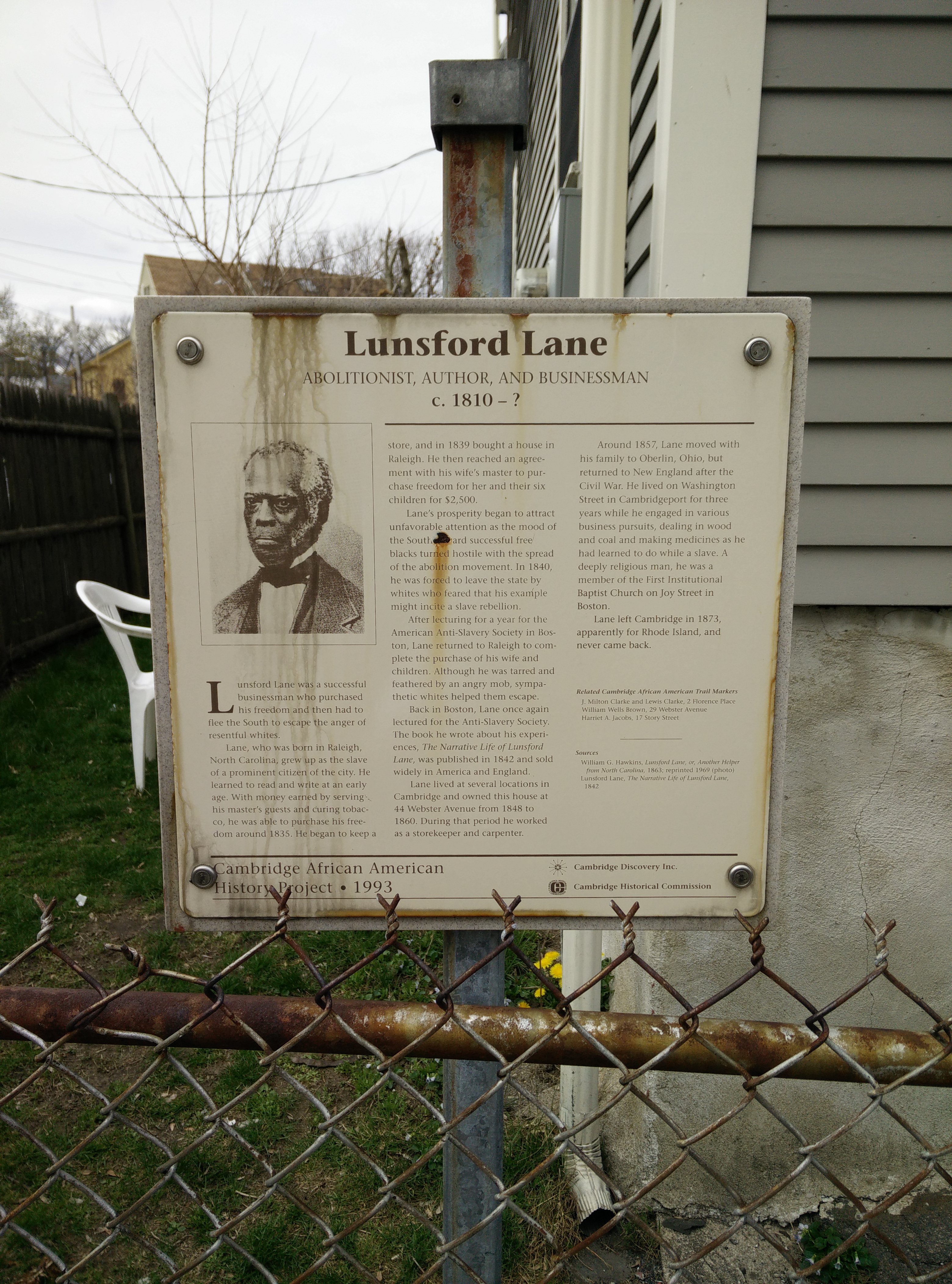

The cultural shaping of the site continues with the dedication of street corners to famous abolitionists and minority advocates. As Hayden states “An ordinary urban neighborhood will also contain the history of activists who have campaigned against spatial injustices…it is possible to identify historic urban places that have special significance to certain populations fighting spatial segregation of different kinds” (39). An example of such a memorial is found outside a seemingly ordinary home on Webster Street (pictured left). This “memorial” was commissioned in 1996, according to the sign’s text. This indicates a seemingly unfounded desire to commemorate social precedents, considering Lumsford Lane lived over two centuries ago. However, the social and technological influence he had (he was also a scientist) must appeal to the sphere of innovation contained in Kendall Plaza.

Consideration of historical social relationships helps to build up the community because it creates a model to which any member of the community can relate. Social forces shape the site, whether it is immigration or inequity. Acutely summarized by Hayden, “Space is permeated with social relations; it is not only supported by social relations but it is also producing and produced by social relations” (41). The idea of community-driven preservation is most beautifully summarized in the mural on the corner of Portland Street and Hampshire Street, seen below.

MOTT. 'The Area 4 Story.' 2012. Boston. 'One Day in Kendall Square.' Photograph. 27 Apr 2015.

MOTT. 'The Area 4 Story.' 2012. Boston. 'One Day in Kendall Square.' Photograph. 27 Apr 2015.

This public display of the area’s economic and social history is quite fascinating, because it shows the level of dedication that the citizens feel towards the preservation of their history. When this shining example of foundational society is combined with the degrading form of the Cambridge Electrical Company, the result is quite interesting.

Here, it is clear to see two layers. The first is failed industry, and the second is memorialized rememberance of such an industry. Although a park has been built to the left of the ruined building, there seems to be no desire to remove the structure, despite its degrading façade and ivy-covered walls. This trace of a former industry is most likely a sign that the community values its economic beginnings, and is being preserved by allowing it to naturally degrade.

The final example of community development manifests itself in the preservation of small businesses on the site. Specifically, the presence of Emma’s Pizzeria and Advance Tire and Car Care Center played a significant role in the way inhabitants interact with the site. These small businesses have been on the site in some form for nearly a century, adding to the culture and historical richness of the site. Strangely enough, Emma’s has seen the rise and fall of a much larger commercial building beside it, providing an interesting case of historical layers.

The restaurant itself is an artifact of the Italian immigration. As mentioned earlier, marginalized people tended to express themselves through the food culture. The restaurant therefore stands for a much more important historical event, and the fact that it remains is proof that there is respect for the history and culture associated with it.

The Advance Tire and Car Care Centers demonstrates similar characteristics (pictured left). In fact, the shop is located on “Mechanic Square:” the same place as the abandoned Cambridge Electric Company Building. While this artifact also seems fairly decrepit, it has been allowed to stay, perhaps as a testament to the importance of the automobile for the site. As a whole, maybe Mechanic Square is meant to house the remnants of the mechanized profession, creating a memorial to the older craft as the glass BioTech industries rises just across the street.

Throughout my site, there are many examples of artifacts and layers that support the idea of a trend towards fostering a community based on historical precedents. The initial development of land into separate industrial and residential zones would set the stage for future development. As the industrial area of my site begins redeveloping to address the needs of a growing technological industry, it also is repurposed to meet the demands of an increasing sense of community. Likewise, the preservation of buildings and social culture in the residential area is a response to the desire to maintain historical foundations.

--------------------------------

References

Hayden, Dolores. "The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History." Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. 1995.