A view of some impressive Boston architechture from the street

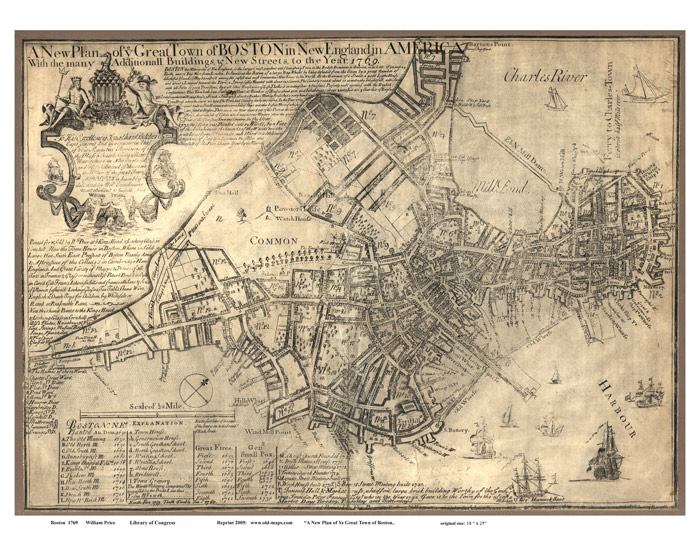

Despite humanity’s continual efforts to conquer and dominate the earth, Mother Nature still rules over the planet, as she has, and will continue, for eons. Although humans have built impressive cities as testament to the success of our species, the urban environment has been, is, and will be shaped by natural process uncontrollable by man. Although we have learned to divert water, transport waste, redirect wind, funnel traffic, and preserve green space in our cities, there will always be evidence of nature’s presence in the concrete jungle. Natural processes continue to affect life in the city, sometimes in unexpected and spectacularly powerful ways. Whether it’s a deep crack in the pavement due to rising groundwater, or a tree growing horizontally to stretch toward sunlight, nature leaves clues to its activities all over the city. After learning and understand what clues to look for, one can start to see patterns and processes everywhere in the city. In the 4 square blocks starting at the intersection of Commonwealth Ave. and Clarendon St. and extending to Boylston Ave. and Arlington St. in Boston, one can find an abundance of natural processes that are either written into geological history, or presently ongoing. In this area, natural processes have allowed people to enjoy a carefully planned landscape and a breathtaking array of city nature, while also creating inconveniences to residents, ranging from damaged sidewalks to inaccessible alleyways and gusty winds. But before examining evidence of ongoing natural processes in the city, we must first understand the environmental history of the area. Boston was founded, and first settled in 1630 by Puritans from England ("Boston | Massachusetts, United States." Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Accessed March 2, 2015) Since then, the settlement has grown into one of America’s largest cities. Originally, as seen in Figure 1, Boston was located on a small peninsula. Surrounded by water, the city was connected to the mainland only by a single small strip of land. The surrounding water made Boston a critical port for the early colonies, and established the city as a major shipping and manufacturing hub.

Figure 1: A map of Boston from 1769, used with permission from www.old-maps.com

Figure 1: A map of Boston from 1769, used with permission from www.old-maps.com

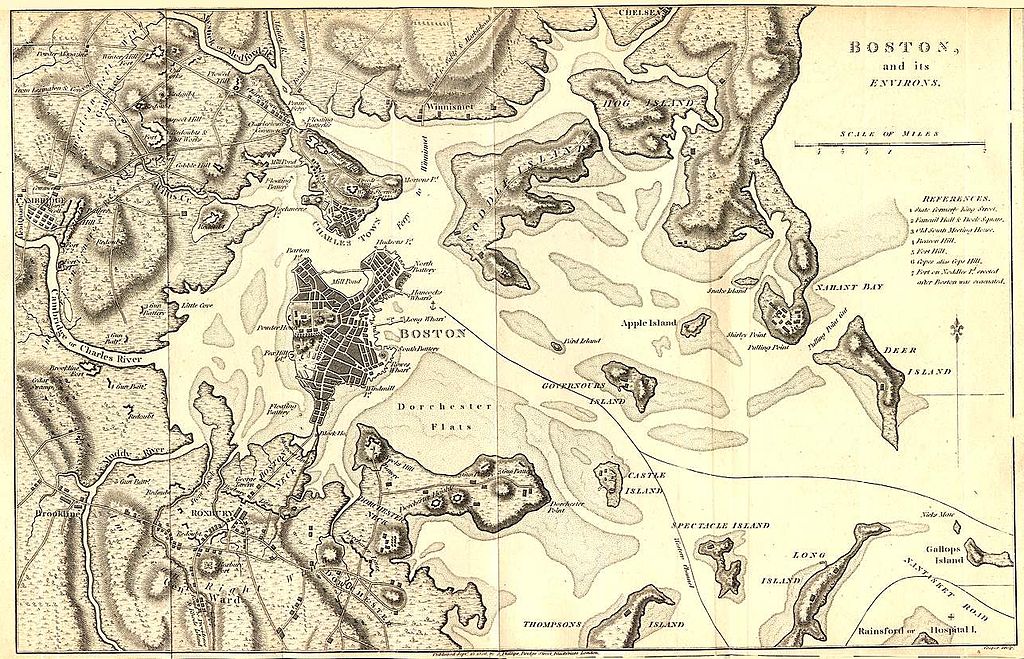

What Boston looks like to us now is far from what it was at the start of its life. Much of the modern city of Boston was constructed on filled land. Figure 2 is a map of the city in 1806, before the land reclamation took place. Seen here is also the entire city, concentrated on the peninsula. The leftmost side of the peninsula is still recognizable today, as Boston Common. We will use the Common as a geographic reference point for the historical location of the Clarendon-Commonwealth to Boylston-Arlington site, hereafter referred to simply as the Site. The Site is today adjacent to the Public Gardens, invisible in figures 1 and 2, which borders the Common. The approximate location of the Site is marked on each of the figures for emphasis.

Figure 2: The Boston peninsula in 1806

Figure 2: The Boston peninsula in 1806

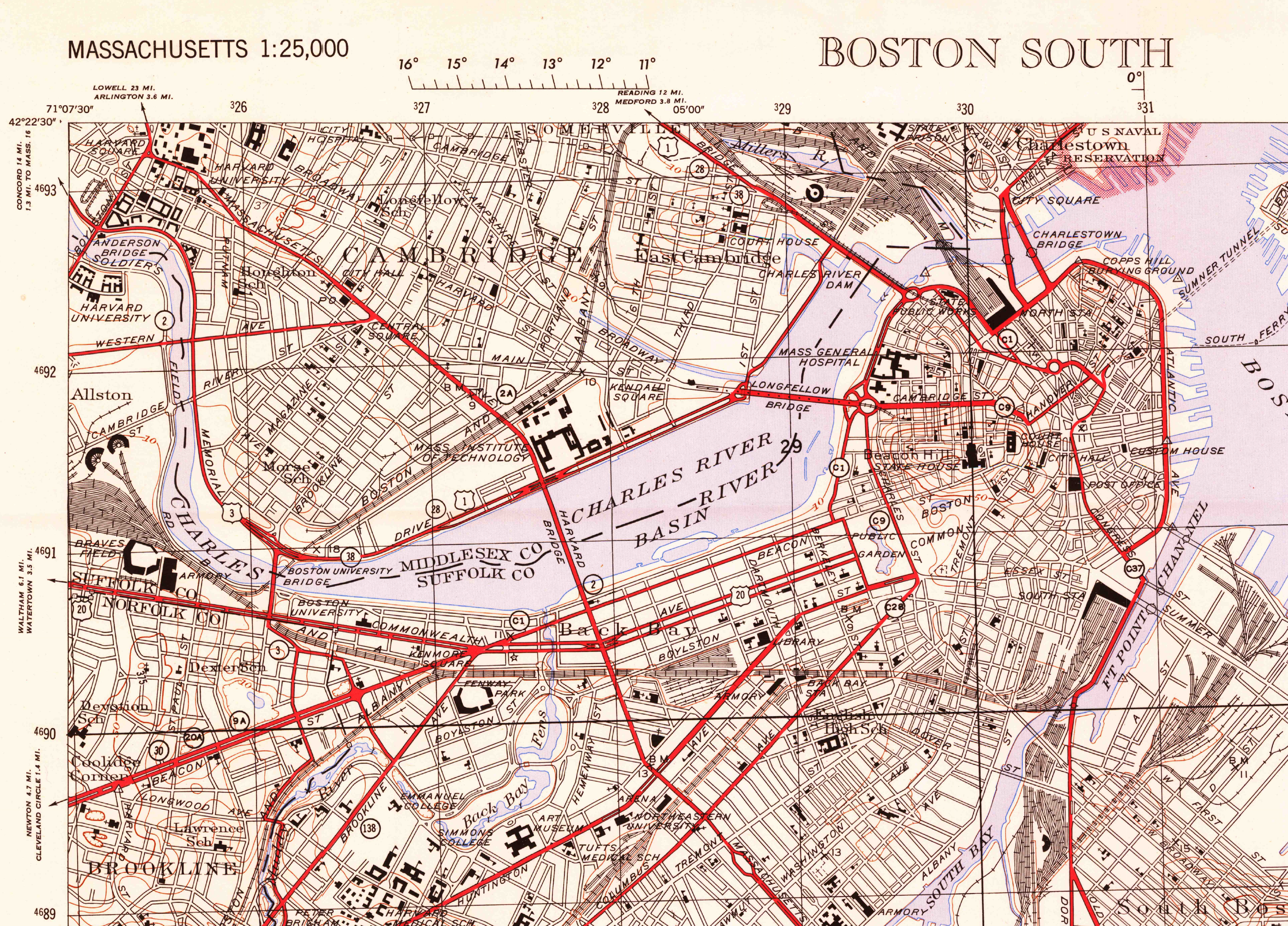

Turning our attention to Figure 3, we are presented with a completely different picture of Boston. Clearly from 1814 to 1880 the city as a whole underwent stunning geographic growth. This can, in part, be attributed to the land reclamation project, which created a larger connection to the mainland, along with new neighborhoods. The project also provided city planners with the opportunity to design the newly filled area. Looking at the Site in Figure 3 we can see that it is part of a structured grid system.This was deliberately chosen to provide order in the newly created urban area. It is also evident that the geographic structure of the Site has remained unchanged since the reclamation project. Figure 4, a map from the 20th century, shows how the urban landscape and street structure remained identical following the filling of land. Thus, the Site holds within it great historical significance, and insights into the minds of city designers of the 19th century.

An interesting observation can be made to the number of churches in the area. In just 4 square city blocks there are 2 churches, each founded at different times by different religious sects. A Presbyterian church is located on the corner of Newbery and Berkeley, and a Unitarian Universalist church is on the corner of Arlington and Boylston.

A structure that dominates the area is the Taj Boston. The monolithic hotel not only takes up about a third of a city block, but also has influenced the surrounding businesses to cater to the wealth of the individuals who stay in the hotel. Surrounding the Taj are high-end designer fashion boutiques, namely Burberry, Tiffany, and Cartier among others. Another building, Restoration Hardware, takes up a significant portion of a block. It is isolated from any other structure, and serves both a commercial and tourism purpose in the area.

The site also contains the Arlington T stop along the green line. The development of public transit in a city is a vital step in its growth. Evidence and remnants of this development can surely be found within this site. Cities only exist because of human traffic flow, which is both increased and altered by public transit.

Figure 3: A map of Boston in 1880, following the massive land reclamation project

Figure 3: A map of Boston in 1880, following the massive land reclamation project

Figure 4: A map of Boston in 1954. U.S> Geological Survey. Boston South, Massachusetts [map]. 1:25,000. Washington, D.C.: USGS, 1954

Figure 4: A map of Boston in 1954. U.S> Geological Survey. Boston South, Massachusetts [map]. 1:25,000. Washington, D.C.: USGS, 1954

The original designers of the city included urban features into the area of the Site to improve overall city function. First, alleyways were constructed between streets to increase accessibility. They were also slanted downward to improve drainage and allow delivery access to a lower level. Second, designers placed a public garden directly adjacent to the Common. This essentially increased the size of the public park space in the city, which was perhaps done to mitigate the introduction of more urban environments. The public garden also contains a lake, a natural feature that provides the city with environmental benefits along with a social gathering area. Bodies of water cool the surrounding area, and provide a habitat for birds in the warmer months. The designers also located a long strip of tree cover along the center of Commonwealth Ave. This walkway serves several purposes, both environmental and social. People can use it as a scenic walk down the city, or a place to jog without the concern of vehicles. The Commonwealth mall also splits the roadway in 2, helping traffic flow Finally, the trees help to filter pollutants and improve air quality in the area, in addition to providing shade in the summer. This nature walk in the middle of the city gives the entire area a feeling of openness and tranquility, a nice contrast to the busyness and more urban Newbury St. and Boylston Ave. The Commonwealth Avenue Mall is not only a showcase for beautifully intricate sculptures of influential public figures in Boston’s history or a tranquil nature walk. It is a place of urban natural processes in action. The immediate area around the mall also shows evidence of natural progression. The trees along the walk provide the greatest insights. Trees are living organisms that shape, and are shaped by the environment around them. Their roots extend far underground to search for nutrients in the soil while their branches reach for the skies in the pursuit of sunlight. In a city, both of these critical resources are in short supply for most trees. Because of the lack of open, healthy soil, many city trees have stunted growth and thin branches. Looking at the average street tree, planted in a circular plot of land on the sidewalk barely larger than itself, surrounded by concrete, it is hard to imagine how anything could survive (Figure 5). Water has difficulty draining down to the ground beneath the pavement, and what does is often polluted. Not only is there little soil for the tree to extract nutrients from, but the ground surrounding it is constantly contaminated by street pollutants, whether from pedestrians, residents, or automobiles. (Spirn, Anne Whiston. The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design. New York, New York: Basic Books, 1984) Sunlight is another scarce resource in most dense city areas. Buildings block light, which often only filters through to the center of streets during the middle of the day. Even worse, some buildings are positioned in ways that make tree growth almost impossible. This forces trees to grow in abnormal patterns to try and reach what little bit of light they can.

Figure 5: A typical street tree located on Arlington Ave. In the background one can see its larger cousins living in the Common.

Figure 5: A typical street tree located on Arlington Ave. In the background one can see its larger cousins living in the Common.

Figure 6: A photo of the Commonwealth Mall, showing the differences in sizes between trees in the area.

Figure 6: A photo of the Commonwealth Mall, showing the differences in sizes between trees in the area.

Figure 7: A tree on Commonwealth Ave. trying desperately to stretch towards sunlight.

Figure 7: A tree on Commonwealth Ave. trying desperately to stretch towards sunlight.

Figure 8: A street tree along Newbury St.

Figure 8: A street tree along Newbury St.

Figure 9: A photo of an interesting crack formation in the pavement.

Figure 9: A photo of an interesting crack formation in the pavement.

Figure 10: A breathtaking image of icicle formation in Boston alleyways.

Figure 11: A photo of a manument in Commonwealth Mall. Notice how people have chosen to walk around the sculpture mostly on one side, as indicated by the snow melting pattern.

Figure 11: A photo of a manument in Commonwealth Mall. Notice how people have chosen to walk around the sculpture mostly on one side, as indicated by the snow melting pattern.

Figure 12: A completely snowed-in parking spot that has been rendered unusable by the weather

Figure 13: A photo of the front side of the Emmanuel Church in Boston, showing how wind patterns dump snow in certain areas surrounding buildings.

Figure 14: The steps to this church have been completely covered by snow. Ironically, the weather has made this entrance all the more inaccessible.